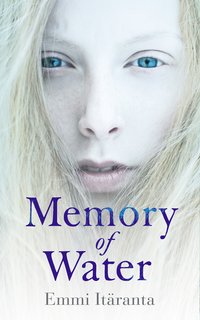

Memory of Water

Minja was Sanja’s two-year-old little sister who had been sick constantly since her birth. Lately their mother Kira had also been unwell. I had not told Sanja, but once or twice in the half-light of late evening I had seen a stranger sitting by their door, a dark and narrow figure, not unkind but somehow aware that it wouldn’t be welcomed anywhere it went. It had been still and quiet, waiting patiently, not stepping inside, but not moving away, either.

I remembered what my father had told me about death and tea masters, and when I looked at Sanja, at the shadows of unslept hours on her face that wasn’t older than my own, the image of the figure waiting by their door suddenly weighed on my bones.

Some things shouldn’t be seen. Some things don’t need to be said.

‘Have you applied for permission to repair the water pipe?’

Sanja gave a snort. ‘Do you think we have time to wait through the application process? I have almost all the spare parts that I need. I just haven’t figured out how to do it without the water guards noticing.’

She said it casually, as if talking about something trivial and commonplace, not a crime. I thought of the water guards, their unmoving faces behind their blue insect hoods, their evenly paced marching as they patrolled the narrow streets in pairs, checking people’s monthly use of their water quotas and carrying out punishments. I had heard of beatings and arrests and fines, and whispers of worse things circulated in the village, but I didn’t know if they were true. I thought of the weapons of the guards: long, shiny sabres that I had seen them cut metal with, when they were playing on the street with pieces of an illegal water pipe they had confiscated from an old lady’s house.

‘I brought you something to repair,’ I said and began to unfasten the straps from around my load of waterskins. ‘There’s no rush with these. How much will you charge?’

Sanja counted the skins by tracing her finger along the pile. ‘Half a day’s work. Three skinfuls.’

‘I’ll pay you four.’ I knew Jukara would have done the job for two, but I didn’t care.

‘For four I’ll repair one of these for you right away.’

‘I brought something else too.’ I took a thin book out of my bag. Sanja looked at it and made a little sound of excitement.

‘You’re the best!’ Then her expression went dark again. ‘Oh, but I haven’t finished the previous one yet.’

‘Doesn’t matter. I’ve read them many times.’

Reluctantly Sanja took the book, but I could see she was pleased. Like most families in the village, her family had no books. Pod-stories were cheaper and you could buy them at any market, unlike paper.

We carried the skins around the house into Sanja’s workshop, which she had built in the backyard. The roof was made of seagrass and three of the walls consisted of insect nets stretched between supporting wooden poles. The back wall of the house functioned as the fourth wall of the workshop. Sanja pulled the finely-woven wire mesh door closed behind us and latched it so the draught wouldn’t throw it open.

I placed the skins on the wooden planing bench in the middle. Sanja put the rest on top of them and took one to the long table by the solid wall. My father had marked the cut with beetroot colour; it was the shape of an uneven star on the surface of the skin.

Sanja lit the solar burner and its wires began to glow orange-red. She took a box with pieces of patching plastic from under the table and picked one. I watched as she took turns to carefully heat the waterskin and the patch until both surfaces had grown soft and sticky. She fitted the plastic on top of the crack and after making sure that it covered the cut in the skin she began to even the seam out to make it tight.

While I waited, I looked around in the workshop. Sanja had brought in more junk plastic since my last visit a couple of weeks ago. As always, the long tables were filled with tools, brushes, paint jars, wooden racks, empty blaze lanterns and other bits and pieces I didn’t even recognise. Yet most of the space was taken up by wooden boxes spilling over with junk plastic and metal. Metal was more difficult to find, because the most useful parts had been taken to cities for the army to melt down decades ago, and after this people had gathered most of what they could put to good use from metal graves. All you could dig up these days in those places were useless random pieces that had nothing to do with each other.

Junk plastic, on the other hand, never seemed to run out, because past-world plastic took centuries to degrade, unlike ours. A lot of it was so poor in quality or so badly damaged that it couldn’t be moulded into anything useful, but sometimes, if you dug deeper, you could come across treasures. The best finds were parts of the broken technology of the past-world, metal and plastic intertwined and designed to do things that nothing in our present-world did anymore. Occasionally a piece of abandoned machinery could still be fairly intact or easily repaired, and it puzzled us why it had been thrown away in the first place.

In one of the boxes under the table I found broken plastic dishes: mugs, plates, a water jug. Under them there were two black plastic rectangles about the size and shape of the books I had in my room at home, a few centimetres thick. They were smooth on one side, but on the reverse side there were two white, round wheel-like holes with cogs. One of the edges on one of the rectangles was loose and a shredded length of a dark, shiny-smooth tape had unravelled from the inside. There was small print embossed on the plastic. Most of it was illegible, but I could make out three letters: VHS.

‘What are these?’ I asked.

Sanja had finished smoothing the seam and turned to look.

‘No idea,’ she said. ‘I dug them up last week. I think they’re changeable parts to some past-tech machine, but I can’t think of what they were used for.’

She placed the skin on a rack. It would take a while for the plastic to seal completely. She picked up a large rucksack from the table and lifted it on her back.

‘Do you want to go scavenging while the skin cools down?’ she asked.

When we had walked a few blocks, I was going to turn to the road we usually took to the plastic grave. But Sanja stopped and said, ‘Let’s not go that way.’

The mark caught my attention at once. There was a wooden house by the road. Its faded, chipped paint had once been yellow, and one of the solar panels on the roof was missing a corner. The building was no different from most other houses in the village: constructed in the past-world era and converted later for the present-world circumstances. Yet now it stood out among the washed-out, colourless walls and faded yards, because it was the only house on the street that had fresh paint on its door. A bright blue circle was painted on the worn wooden surface, so shiny it still looked wet. I hadn’t seen one before.

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘Let’s not talk here,’ Sanja said, pulling me away. I saw a neighbour step out of the house next door. He avoided looking at the marked house and accelerated his steps when he had to walk past it. Apart from him, the street was deserted.

I followed Sanja to a circuitous route. She glanced around, and when there was no one in sight, she whispered, ‘The house is being watched. The circle appeared on the door last week. It’s the sign of a serious water crime.’

‘How do you know?’

‘My mother told me. The baker’s wife stopped at the gate of the house one day, and two water guards appeared out of the blue to ask what her business was. They said the people living in the house were water criminals. They only let her go after she convinced them that she had only stopped by to sell sunflower seed cakes.’

I knew who lived in the house. A childless couple with their elderly parents. I had a hard time imagining they were guilty of a water crime.

‘What has happened to the residents?’ I asked. I thought of their ordinary, worn faces and their modest garments.

‘Nobody knows for sure if they’re still inside or if they’ve been taken away,’ Sanja replied.

‘What do you think they’re going to do with them?’

Sanja looked at me and shrugged and was quiet. I remembered what she had said about building an illegal water pipe. I glanced behind me. The house and the street had disappeared from sight, but the blue circle was still flashing in front of my eyes: a sore tattoo on the skin of the village, too inflamed to approach safely, and covered with silence.

We continued along a circuitous route.

We crossed a shallow, muddy brook that trickled through the landscape near the plastic grave. As children we had not been allowed here. My mother had said that the ground around it was toxic and the grave dangerous to walk on, a foot could slip at any time and something sharp tear the clothes and the skin. Back then we used to plan our secret excursions to the plastic grave carefully, usually coming between day and night, when it wasn’t dark enough for us to need blaze lanterns yet and not light enough for us to be recognisable from a long way away.

The plastic grave was a large, craggy, pulpy landscape where sharp corners and coarse surfaces, straight edges and jagged splinters rose steep and unpredictable. Its strange, angular valleys of waves and mountain lines kept shifting their shape. People moved piles of rubbish from one place to the next, stomped the plains even more tightly packed, dug big holes and elevated hills next to them in search of serviceable plastic and wood that wasn’t too bent out of shape under layers of garbage. The familiar smell and sight of the grave still brought me back the memory of the long boots I had always worn in the fear of scratching my legs, the coarseness of their fabric, how hot and slippery my feet had felt inside them.

Now I was only wearing a pair of wooden-soled summer shoes that didn’t even cover my ankles, but I was older and the day was bright. Dead plastic crunched under the weight of our steps and horseflies and other insects were whirring loudly around our hooded heads. I had rolled my sleeves down and tied them tight at the wrists, knowing that any stretch of bare skin would attract more insects. My ankles would be red and swollen by the evening.

I kept an eye on anything worth scavenging, but passed only uninteresting items: crumbled, dirty-white plastic sheets, uncomfortable-looking shoes with broken tall heels, a faded doll’s head. I stopped and turned to look behind me, but Sanja wasn’t there anymore. I saw her a few metres away, where she had crouched to dig something out of a junk pile. I went closer when she pulled what looked like a lidded box out from a mishmash of split bowls and twisted hangers and long black splinters.

The box was the shape of a rectangle; I had never seen one like it before. The scratched, black surface looked like it had been smooth and shiny once. At each end of the rectangle there was a round dent covered by a tight metal net.

‘Loudspeakers,’ Sanja said. ‘I’ve seen similar ones on other past-tech things. This was used for listening to something.’

Between the loudspeakers there was a rectangular dent, slightly wider than my hand. It had a broken lid that could be opened from the upper corner. On top of the machine there were some switches, a row of buttons with small arrows pointing at different directions embossed on them, and one larger button. When it was turned, a red pointer moved along a scale marked with numerical combinations that meant nothing: 92, 98, 104 and so on. At the right end of the scale the letters ‘Mhz’ could be seen. In the middle of the top panel there was a round indentation, slightly larger than the one in the front panel and covered by a partially transparent lid.

I knew without asking that Sanja was going to take the machine home with her. Her face revealed that she was already picturing the inside hidden by the cover in her mind and seeing herself opening the machine, memorising the order of the different parts, conducting electricity from a solar generator into it in order to see what happened.

We wandered on the plastic grave for a while longer, but we only found the usual rubbish – broken toys, unrecognisable shards, useless dishes and the endless mouldy shreds of plastic bags. When we turned to return to the village, I said to Sanja:

‘I wish I could dig all the way to the bottom. Perhaps then I’d understand the past-world, and the people who threw all this away.’

‘You spend too much time thinking about them,’ Sanja said.

‘You think about them too,’ I told her. ‘You wouldn’t come here otherwise.’

‘It’s not them I think about,’ Sanja said. ‘Only their machines, what they knew and what they left to us.’ She stopped and placed her hand on my arm. I could feel the warm outline of her fingers through the fabric of my sleeve and the burn of the sun around it, two different kinds of heat next to each other. ‘It’s not worth thinking about them, Noria. They didn’t think about us, either.’

I have tried not to think about them, but their past-world bleeds into our present-world, into its sky, into its dust. Did the present-world, the world that is, ever bleed into theirs, the world that was? I imagine one of them standing by the river that is now a dry scar in our landscape, a woman who is not young or old, or perhaps a man, it doesn’t matter. Her hair is pale brown and she is looking into the water that rushes by, muddy perhaps, perhaps clear, and something that has not yet been is bleeding into her thoughts.

I would like to think she turns around and goes home and does one thing differently that day because of what she has imagined, and again the day after, and the day after that.

Yet I see another her, who turns away and doesn’t do anything differently, and I can’t tell which one of them is real and which one is a reflection in clear, still water, almost sharp enough to be mistaken for real.

I look at the sky and I look at the light and I look at the shape of the earth, all the same as theirs, and yet not, and the bleeding never stops.

We spoke little on our way back to Sanja’s house.

She stood in the shadow of the veranda when I fastened the repaired waterskin to the cart and stepped on the pedal of my helicycle. The day around us blazed tall and bright, and she was small and narrow and grey-blue in the dark shadow.

‘Noria,’ she said. ‘About the charge.’

‘I’ll bring you the first two skinfuls later today,’ I said. When I started towards the tea master’s house, I saw her smile. It was thin and colourless, but a smile nevertheless.

My father would not be pleased.

CHAPTER THREE

Late in the following afternoon I climbed the path from the teahouse towards the gate. I stopped on the way by the rock garden to pick some mint. The pale sand rippled around dark-grey boulders like water surrounding abandoned islands. The three tea plants growing just outside the edge of the sand burst towards the clear sky like green flames. I put the mint leaves in my mouth and continued to the small hillock in the shadow of a pine tree by the gate, from where I could see the road through the shadows of the scattered trees. The most burning heat of the day had already passed and the ceremony outfit felt cool and pleasant against my skin. Yet the hard-soled sandals were uncomfortable under my tired feet, and my arms ached.

My father had risen after a few short hours of sleep in the pale-gold light of a white night turning to morning. He didn’t always wake me this early on ceremony days, but this time he knew no mercy. I knew it to be my unspoken punishment for having stayed too late at Sanja’s house on the day before. He gave me one task after another, sometimes three at once, and by the time my mother got up for breakfast, I had already raked the rock garden, carried several skinfuls of water into the teahouse, swept the floor twice, hung decorated blaze lanterns inside and outside, aired the ceremony clothing, washed and dried the teacups and pots, placed them on a wooden tray, wiped dust from the stone basin in the garden and moved the bench on the veranda three times before my father was happy with its exact position.

It was with relief, then, that I walked to the gate to wait for our guests, when he finally released me from my preparation duties. I had eaten hardly anything since breakfast, and I chewed on the mint leaves to chase my hunger away. In the weary sunlight of the afternoon I had trouble keeping my eyes open. The faint tinkling of wind chimes in the garden flickered in my ears. The road was deserted and the sky was deep above, and all around me I sensed small shifts in the fabric of the world, the very movement of life as it waxed and waned.

Wind rose and died down again. Hidden waters moved in the silence of the earth. Shadows changed their shapes slowly.

Eventually I saw movement on the road, and little by little I began to make out two blue-clad figures in a helicarriage driven by a third one. When they reached the edge of the trees, I hit the large wind chime hanging from the pine. A moment later I heard three chinks from the direction of the teahouse and knew that my father was ready to receive the guests.

The helicarriage stopped near the gate in the shadow of a seagrass roof built for guest vehicles and two men in the military uniforms of New Qian stepped down from it. I recognised the older one: his name was Bolin, a regular tea guest who came every few months all the way from the city of Kuusamo and always paid well in water and goods. My father appreciated him because he knew the etiquette of tea ceremony and never demanded special treatment despite his status. He was also familiar with the local customs, being originally from our village. He was a high-ranked official and the ruling military governor of New Qian in the occupied areas of the Scandinavian Union. His jacket carried insignia in the shape of a small silver fish.

The other guest I had not seen before. From the two silvery fish tagged on his uniform I understood that he was of even higher rank than Bolin. Even before I saw his face through the thin veil of the insect hood, his posture and movements gave me the impression that he was the younger of the two. I bowed and waited for them to bow back in response. Then I turned to the garden path. I walked ahead of them at a deliberately slow pace in order to give them time to descend into the unhurried silence of the ceremony.

The grass at the front of the teahouse shimmered in the sun: my father had sprinkled it with water as a symbol of purity, as was the custom. I washed my hands in the stone basin which I had filled before, and the guests followed my example. Then they sat down on the bench to wait. A moment later a bell chimed inside the teahouse. I slid the door of the guest entrance to the side and invited the guests to move inside. Bolin kneeled at the low entrance with some difficulty, then crawled through it. The younger officer stopped and looked at me. His eyes seemed black and hard behind the insect hood.

‘Is this the only entrance?’ he asked.

‘There is another one for the tea master, sir, but guests never use it.’ I bowed to him.

‘In cities one hardly finds tea masters anymore who require their guests to kneel when entering,’ he replied.

‘This is an old teahouse, sir,’ I said. ‘It was built to follow the old idea that tea belongs to everyone equally, and therefore everyone equally kneels before the ceremony.’ This time I didn’t bow, and I thought I saw annoyance on his face before his expression settled into an unmoving polite smile. He said no more, but dropped down on his knees and went through the entrance into the teahouse. I followed him and slid the door closed behind me. My fingers trembled lightly against the wooden frame. I hoped no one would notice it.

The older guest had already settled by the adjacent wall and the younger one sat down next to him. I sat down by the guest entrance. My father was sitting on his knees opposite to the guests, and as soon as we had removed our insect hoods, he bowed.

‘Welcome, Major Bolin. This is a long-awaited pleasure. Too much water has flown since you last visited us.’ He was keeping strictly to the etiquette, but I could hear a slight warmth in his voice, only reserved for friends and longtime customers.

Major Bolin bowed in response.

‘Master Kaitio, I take pleasure in finding myself in your teahouse again. I have brought a guest with me, and I hope he will enjoy your tea as much as I do.’ He turned to his companion. ‘This is Commander Taro. He has only just moved here from a faraway southern province of New Qian, and I wished to welcome him by treating him to the best tea in the Scandinavian Union.’

Now that he wasn’t wearing his insect hood I could see clearly that Taro was younger than Bolin. His face was smooth and there was no grey in his black hair. The expression on his face did not change when he bowed his greeting.

After my father had welcomed Taro with another bow, he went into the water room and returned shortly carrying a cauldron. He placed it into the hearth in the floor on top of dried peat, which he lit with a firestarter. The flintstones crackled against each other. I listened to the rustling of his clothes as he went into the water room again and returned with a wooden tray laden with two teacups and two teapots, a large metal one and a small earthenware one. He placed the tray next to the hearth on the floor and chose his own place so that he could see the water in the cauldron. I knew Major Bolin to favour green tea that required the water not to be too hot. ‘When you can count ten small bubbles at the bottom of the cauldron, it is time to raise the water into the teapot,’ my father had taught me. ‘Five is too few and twenty is too many.’

When the water had reached the right temperature, my father scooped some of it from the cauldron into the large teapot. As a child I had followed his movements and tried to imitate them in front of a mirror until my arms, neck and back ached. I never reached the same smooth, unrestrained flow that I saw in him: he was like a tree bending in wind or a strand of hair floating in water. My own movements seemed clumsy and rigid compared to his. ‘You’re trying to copy the external movement,’ he would say then. ‘The flow must come from the inside and pass through you relentlessly, unstopping, like breathing or life.’

It was only after I began to think about water that I began to understand what he meant.

Water has no beginning and no end, and the tea master’s movement as he prepares the tea doesn’t have them, either. Every silence, every stillness is a part of the current, and if it seems to cease, it’s only because human senses aren’t sufficient to perceive it. The flow merely grows and fades and changes, like water in the iron cauldron, like life.

When I realised this, my movements began to shift, leaving the surface of my skin and my tense muscles for a deeper place inside.

My father poured water from the large teapot into the smaller one, which held the tea leaves. Then he poured this mild, swiftly brewed tea from the smaller pot into the cups in order to warm them up. As a final step of preparation, he filled the small teapot again and drenched it with the tea from the cups, soaking the earthenware sides of the pot while the leaves inside were releasing their flavour. The blaze lanterns hanging from the ceiling sprinkled softly flickering light on the water as it spread on the tray. Breath by breath I let myself sink into the ceremony and took in the sensations around me: the flare of the yellowish light, the sweet, grassy scent of the tea, the crinkle in the fabric of my trousers pressing at my leg, the wet clank of the metal teapot when my father placed it on the tray. They all entwined and merged into one stream that breathed through me, chasing the blood in my veins, drawing me closer and deeper into the moment, until I felt as if I wasn’t the one breathing anymore, but life itself was breathing through me, connecting me to the sky above and earth below.