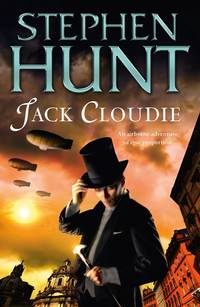

Jack Cloudie

The man thumped at his chest and hacked out a sawing cough out before croaking. ‘You think the world’s changed much since then?’

‘No.’ Although I had so hoped my world would have. My biggest problem should have been explaining where the sudden shower of gold guineas had appeared from to buy back our estate.

‘Have a look for news of the match workers’ strike,’ said a woman who looked like she might be the mother of one of the families. ‘Are they still bringing in blacklegs to break the strike?’

Jack leafed through the sheaf of large sheets, dark ink staining his fingers, imprinting them from the damp. ‘No mention of the unions here, lady. It’s all talk of a possible war brewing with the Cassarabians.’ They looked up at him, disappointed. There were dozens of families in the cell who had been accused of tearing up cobblestones and throwing them at a factory owner. The recent confrontation between the match workers’ union and the guards who’d been paid to keep the mill open had filled the holding cells.

Jack pointed to the cartoon on the front of the newssheet. A pregnant woman was stretched across a doctor’s table being attended to by a gaggle of surgeons with the faces of famous politicians. A plump young Jackelian boy wearing the uniform of the Royal Aerostatical Navy was jumping up and down in a jealous fit at the sight of a grotesque baby – clearly a Cassarabian – being delivered; the babe also dressed in an opulent airship officer’s uniform. ‘You have a rival, Jack,’ noted the voice balloon hanging over the leering surgeon’s head. ‘Confound you,’ the plump boy was yelling. ‘You promised me nary a sibling.’

‘A bad business,’ said the man.

Jack had to agree. His namesake in the illustration was a Jack Cloudie, an airshipman, and for centuries the monopoly the Kingdom had exercised over the celgas that floated the RAN’s four fleets of airships had kept the nation safe from foreign invasion. Now their belligerent neighbours to the south had secured a supply somehow, and a rival aerial fleet had been spotted patrolling the Jackelian–Cassarabian borders along the uplands. A bad business, indeed. And devilish worse when you’d been sentenced to service in the regiments. First in line when it came to being marched into a fusillade of Cassarabian cannon fire. How much could the world change in two weeks? Always for the worse, that was Jack’s experience. Always for the worse.

The man looked at Jack. ‘What did you get, the boat or the regiments?’

‘The army.’

‘Me too.’ There was a wave of weeping from the woman and her children at that. Of course, it would be transportation to the colonies for them. Without their father. Without her husband. ‘All my life I’ve laboured morning, day and evening. We were just standing on the picket line when management’s men cleared us out with whips and canes. That’s all, just standing there. All my life I’ve done the right thing.’

His voice trailed off.

At least someone here knows what that is.

‘On your feet,’ called the court constable, dragging his cosh along the iron bars of the cell. Jack woke coughing, blinking at the fierce light of the lamp in the policeman’s hand. There were a couple of hulking red-coated soldiers behind the constable, a sergeant and a corporal, the yellow light of the lamp reflected ominously on the death’s heads of their oiled shako hats. The two men fairly strutted along with their left hands balanced on their sheathed sabres to stop them bumping along the damp stone floor. The pair of soldiers might have been Boyd’s older brothers judging by the arrogance of their gait and the unvoiced capacity for violence they left hanging in the air around them.

‘Is this all you have for us?’ said the sergeant, disdainfully.

Jack rubbed the sleep out of his eyes. What were you expecting? A cell full of smartly dressed officers, expert duellists and marksmen for you to press gang into your suicide squad?

‘Not much to look at,’ said the court constable, waving dismissively at the prisoners. ‘But we don’t feed them a fighting man’s rations in here. Give them a plate of gruel and a bayonet and they’ll stick someone for you right enough. Most of them already have.’

‘On your feet, my raggedy boys,’ yelled the sergeant. ‘Move as if you had a purpose – and that was to be chosen by the hand of parliament to serve in its glorious army.’

‘Come on, come on!’ yelled the corporal. ‘Jump to it.’

Jack listened to the creaking of his reluctant bones, a product of the damp, as he joined the others in the cell shuffling through the door that had been opened for them, their leg chains still attached to their ankles. Where were his chains to be removed, Jack wondered? Behind the safe, high stockade of some New Pattern Army barracks, no doubt. Jack felt a sting on the back of his neck as the sergeant encouraged him along with a flick of a swagger stick. ‘Step lively, now. I’ve seen more bleeding life in a fella flogged for sleeping on duty.’

Jack’s wound smarted like a bee sting and he wasn’t the only one to receive some lumps at the hands of the two soldiers sent to collect the convicts. There was an army carriage waiting for them at the other end of the holding cell’s passage, a segmented iron-hulled thing with large spoked wheels. Two soldiers stood in front of it, a man and a female officer, both in brown oiled greatcoats. The appearance of the officer seemed to disconcert the pair of brutes dragging Jack into military service and no wonder. The woman had an angelic face, but frozen with a cold superiority that sat ill at ease with her smooth skin and elegant features; wide eyes that should have radiated softness, glimmered with a piercing intensity instead. She was beautiful the same way an assassin’s dagger was. You might admire it, but only a fool would want to take a closer look.

The male soldier, a broad-shouldered bear of a man with a forked beard salted white with age, came to attention and stamped his boot on the street’s cobbles. ‘The prisoners, lieutenant.’

‘Very good, Oldcastle,’ said the woman.

Both brutes shepherding the convicts into the light halted and saluted back – in what seemed to Jack a rather cursory way – towards the female lieutenant. ‘Prisoners of the Twenty-Second Rifles, sir. The Third Penal Battalion.’

‘Only so long as they don’t escape,’ said the lieutenant.

‘Ah, you’re lucky indeed we caught you two boys in time,’ said the soldier the female officer had named as Oldcastle. He banged the side of the armoured carriage. ‘This old clunker is fine to hold run-of-the-mill ruffians from Bonegate jail, but not this imp!’ His fat fingers jabbed towards Jack. ‘Why, the slippery rascal is the same fellow whose clever fingers nearly teased open the vault of Lords Bank. The locks on the back of your carriage are like bread and butter to a wicked clever thief like this one.’

‘We have sole custody, sir.’

‘House Guards sent us,’ announced the female lieutenant. ‘The general staff want Jack Keats in a secure stockade cell by the end of the day while they consider what to do with him.’

They do?

‘Of course, lads,’ winked Oldcastle. ‘If you want to keep hold of his sly bones, just write us a little note saying that you wouldn’t discharge him across to us. Two strapping fellows like you to look after the pup, he probably won’t escape, will he? The general staff will understand. Look at the thin rascal; why, I reckon the smoke rising from a good hot beef broth might blow the scrawny, thieving mischief-maker right over.’

The corporal pulled open an armoured door on the carriage for the convicts to board, but the sergeant reached out to stop him. ‘If the boy escapes, we’ll both lose our stripes.’ A key was produced, slipped into Jack’s ankle restraints and the corporal pushed him roughly towards the lieutenant. ‘Your prisoner, sir.’

Jack rubbed the life back into his chaffed shins while the corporal looked knowingly at the old soldier. ‘Keep your eyes on him. Some of these street rats got a turn of speed on them like you wouldn’t expect.’

If you think I can run for it, you’ve never spent a night in those cells.

‘Not a problem, corporal.’ Oldcastle unslung a rifle, a cheap-milled brown bess, the army’s weapon of choice. ‘Why, John Oldcastle could shoot a moustache off this lad’s lips at a thousand yards, were he qualified for growing a man’s set of whiskers.’

The corporal nodded in satisfaction at the answer and the two brutes pushed the rest of their shackled prisoners into the armoured wagon.

Jack was marched around the corner to where a shining civilian horseless carriage was waiting, the hum of high-tension clockwork making the air shiver and spooking a horse pulling a coal cart along on the other side of the road. It was the sort of vehicle Jack imagined a general might be chauffeured around in, but the old soldier John Oldcastle pulled himself into the driving pit in the front of the vehicle’s sloped hull while the woman indicated Jack should climb up into the leather passenger seats mounted in the rear. As the lieutenant mounted the steps, her greatcoat fell open, revealing the white facings on her red uniform. Jack’s eyes narrowed in surprise.

‘Do you know what the colour means?’ asked the lieutenant.

‘When you’re in an alehouse,’ said Jack, ‘an army redcoat will drink until he can’t fight. Marines always stay sober enough to dish out some mean lumps.’

John Oldcastle laughed from in front of the carriage. ‘I told you he would be a quick one, Maya. The lad who nearly broke into Lords Bank.’

The woman’s green eyes widened in an appraising stare. ‘Marines stay sober by habit, because they operate under the discipline of a crowded airship, where any jostle that sparks a brawl could lead to fatal damage to a vessel.’ She looked at her sergeant. ‘And Oldcastle, you will address me as First Lieutenant Westwick when others are present.’

‘Yes, sir.’

This odd pair and his situation perplexed Jack. Their uniforms don’t even fit them. First Lieutenant Westwick’s was clearly tailored for a man. This stinks, I can feel it in my bones. ‘Why do you want me …?’

‘Don’t think that I do,’ said the first lieutenant. ‘You wouldn’t be my hundredth choice, let alone my first.’

‘Why does the Royal Aerostatical Navy want me, then?’

The first lieutenant laughed, even as her eyes stayed icy and forbidding. ‘Admiralty House would have gladly let you hang on the gallows, boy. Maybe that’s why we ended up with you. Now, keep your questions to yourself until you’ve learnt how to salute.’

‘I’ll take the lad under my wing,’ Oldcastle called back from the front of the horseless carriage. ‘Keep him on the straight and narrow until he finds his air legs.’

‘Yes, you bloody well will. Could we make this any harder for ourselves?’

‘Beggars can’t be choosers,’ said the soldier, throwing the steering wheel about as he directed the horseless carriage across the capital’s crowded streets.

‘Nothing good will come of this,’ muttered the first lieutenant.

Jack said nothing, although his curiosity was still burning. In truth, he couldn’t agree with the attractive but flinty-looking woman more. Nothing good has happened to me for a long time.

Omar stood on the balcony outside the pavilion that housed his master’s office. He could see over the great house’s fortified walls, look down on the town of Haffa’s white flat-roofed buildings, at the sea glinting like an endless expanse of beaten bronze beyond, and the fishing dhows that stayed close to the coast and still landed generous catches. Other slaves might have stood fretting, wondering if the summons to meet the great Marid Barir might auger a beating for some infraction of the house’s many rules. But what was the point of that when there was a fine view of the harbour to gaze at? Why, he might even be able to watch one of their large paddle steamers come in to dock. The ships needed fresh water for their boilers to drink as much as the Cassarabian people did – using sea water in a ship’s boiler caused rust and eventually explosions when the pressure proved too much.

The guard standing by the master’s door opened it, allowing a tall figure in green-coloured robes to exit; the number fifty-three repeated in ornate script hundreds of times across the shot silk of a priestly dress. It was the high keeper of their house’s sect, and Omar dropped to one knee to give the necessary bow to the great figure. ‘Ben Issman be blessed.’

‘Ben Issman’s blessings upon you too.’ The prince of the church stopped to nod at Omar. Omar snuck a glance upwards. This isn’t usual. Slaves should be invisible to such a great patronage.

‘May I help you, high keeper? I am exceedingly clever and talented for my age and would be happy to put my soul to your service.’

The priest was staring out across the sea that had been Omar’s distraction a second before. ‘I do not think so, my child. I will just stand here a while. There are fish in the sea, and there are men to catch them, all set in place by heaven’s will. How long has the town of Haffa been nestled down there?’

‘For as long as people remember, high keeper.’

‘And perhaps a little longer than that too, eh?’

‘So it may be,’ Omar grinned.

The high keeper patted Omar’s shoulder and walked away as if he was lost in thought. Quite extraordinary. The emir of the church had clearly seen the greatness within Omar where so many others had dismally failed. Omar’s reverie was broken by the cough of the master’s shaven-headed house manager, who was pointing towards the door, left open for him by the guard.

Marid Barir was waiting for Omar behind the wide sparkling surface of his marble-topped desk, the master’s main office silent except for the twisting cooling fan in the ceiling and the cry of the gulls from beyond his massive open window.

Standing up from behind his desk as Omar entered, the short, portly figure brushed his oiled goatee beard while he slowly paced by the window. ‘Good evening to you, Omar Ibn Barir.’

‘Master,’ said Omar. ‘We have filled the traders’ water tanks and loaded all the salt. They will be leaving shortly.’

‘Of course,’ said Marid Barir. ‘But that is not why I have brought you here this night. You have been weighing on my mind, boy.’

‘I am ever your loyal servant, master,’ said Omar bowing and smiling ingratiatingly.

‘You make a very poor one.’

‘I understand everything about water farming, master,’ said Omar, trying to sound hurt.

Marid Barir scowled. ‘At least well enough to keep your desalination line ticking along while you find ever-more inventive ways to skive off. We have tried everything with you. But we never did beat you enough. Would you work harder if I had you flogged every morning?’

‘I would labour mightily even with the weals on my back, master,’ said Omar, trying to keep the smile on his face. ‘With the strength of three normal men.’

‘You are a poor liar,’ said Marid Barir. ‘I think I am done with you, boy.’ He picked up a rubber tube from his desk, opened it and took out a roll of paper to throw at Omar.

‘Master,’ said Omar, glancing at the paper as he unfurled it. ‘What is this?’

‘You were taught to read the panels on your equipment, well enough, boy. What does it look like?’

‘My—’ Omar looked at the elaborate calligraphy on the roll in confusion ‘—my papers of indenture.’

‘You are a freeman from today,’ said Marid Barir. ‘The Ibn is removed from your name. Struck away.’

Omar fought down the rising sensation of confusion, all his certainties, collapsing around him. ‘But why?’

‘There was one week, Omar, when you didn’t wear that perpetual foolish grin of yours. It was a few years ago when you went down to Haffa’s graveyard to try and find the tombstone of your mother.’

‘It was not there,’ said Omar, remembering. But then, mother had just been a slave. How few there were left in the house to remember her after the plague had struck Haffa.

Marid Barir walked to the window and pointed to the hill at the side of the house. ‘You will find her out there.’

‘That is the House of Barir’s family graveyard,’ said Omar.

‘I buried the best of them out there, Omar, after the plague. My wives, my daughters, my sons, my brothers. All of them, but one.’

‘I—’ Omar started.

‘It is not fitting for the last of this house’s blood to die in bondage, Omar Barir. Not even the foolish result of a dalliance with one of my wife’s maids.’

‘But …’ Omar looked at Marid Barir. The great, wealthy Marid Barir, so shrunk by age, by the worries of freemen. My father. Omar was rendered nearly speechless. All these years, he had known he was not fated for the life of a slave. But this? He had never imagined this. ‘Am I to inherit the water farms, the great house, to lead our people?’

‘You misunderstand my intentions, Omar. I have granted you your freedom. I do not intend to shackle you with anything else, least of all running the House of Barir.’

‘You do not intend to …’ The implications of the man’s cold words struck Omar in his heart.

‘My father,’ said Marid Barir, ‘your grandfather, was a renowned caravan master, but he left me nothing. I raised the money to lead my own caravan. I parlayed one trade route into twenty, and then multiplied that into enough to buy a seat on the guild of water farmers, to pay for the first womb mage with the guild spells for our salt-fish. I did this by myself. An ancestor’s wealth is a gilded cage, a curse you cannot escape. Your grandfather was wise enough not to trap his sons in such a cage. This is the gift I pass along to you. It’s a most valuable one.’

‘Then I cannot stay on the desalination lines?’

‘I could not demean the family’s name by having the last son of Barir toiling alongside nomads and slaves.’

‘Then what shall I do?’

‘What is it that you are always saying? Something will come along …’

Omar gawked at his master. No, not my master. My father. Who would have guessed that freedom would feel so uncertain?

‘Congratulations, my son, you have discovered the joys of independence, the consequence of being a freeman. If I had known it would silence your prattling so effectively I might have done it years ago.’

Omar waved his ownership papers at the man, no longer his master. ‘What shall I be?’

‘We are what heaven wills us,’ said Marid Barir.

‘What shall I do? Tell me what I should do now!’ Omar begged.

Marid Barir tapped his greying hair. ‘Think.’ He barked an order and the house manager opened the door. ‘And go.’

Omar looked at the scroll of paper in his hand. It had all the weight of a length of steel pipe from a salt-fish tank.

The house manager shut the door as Omar – Ibn no more – Barir stumbled out.

‘You managed to remove the grin from his mouth, master.’

‘For an hour at least,’ said Marid Barir. ‘Now then, we must make time to prepare.’

The house manager nodded sadly and began to unfurl documents from the satchel he had with him, laying them across the marble table.

Omar blundered down the corridors of the fortified house, all thoughts of the views the pavilions’ windows and gardens afforded an idler forgotten as he struggled to come to terms with his new status. Free. Every certainty of his life broken into pieces. Is this what greatness feels like?

Glancing up he saw Shadisa at the end of the corridor, walking serenely with one of the house cooks, an icebox of fish under her bare arm. Shadisa, the most beautiful of all the women in the house. And he was free. Free to marry her. Surely her scowling-faced father could not object now? Why, if anything, he should thank his stars that the last son of Barir favoured his lowly daughter!

Omar sprinted up to her and held out his ownership papers as if they were a talisman. ‘Shadisa! I am a freeman. I have my papers.’

She looked at Omar as if he had gone mad.

‘Do you not understand? I am not just any freeman. I am the blood of Marid Barir, and he has—’ Omar hesitated, about to say, cast me off. ‘I am my own man.’

Shadisa took the ownership papers Omar was proffering with her spare hand, scanning the contents, and then thrust them back towards Omar as if she was furious at him. ‘You are a fool, Omar. It is you who do not understand.’

‘But …’

‘He has not done this for you,’ said Shadisa, ‘but for himself. It is only to ease his conscience.’

‘I may seek your father out now,’ pleaded Omar. ‘As a freeman.’

Shadisa’s full lips pursed and she forced the papers into Omar’s hand, shaking her head. ‘Go away Omar.’ She turned and fled down the corridor, leaving Omar more confused than ever.

‘Stay away from the house, water farmer,’ warned the cook. ‘Blood of Marid Barir,’ she grunted. ‘After all of this time, to acknowledge you now. Such a fool, such a cruel fool.’

‘Where am I to go?’ Omar nearly yelled out the words.

‘Go back to your wild nomad friend and your stinking salt tanks,’ spat the cook, running after Shadisa.

Omar looked at the crumpled roll of paper in his hand and smashed a fist into the wall, shouting a roar of frustration. Free and poor. Is that why she has rejected me?

He stalked off in search of Alim. In reality, the old nomad had been more of a father towards Omar than Marid Barir ever had. Old Alim would know what was to be done.

For a second, Omar thought that the water traders had changed their minds and returned to the farm. But there were no water-butt laden sandpedes among the group on the rise of the dunes behind the desalination lines, only camels and tall white-robed figures sitting high and proud in their saddles, the bells of the milk goats they kept with them jingling. Alim was walking towards the newcomers, without even the protection of a rifle.

‘Alim! Alim!’ Omar cried. The old water farmer spotted the young man and turned back, orange sand spilling down in front of his boots.

‘Who are these people?’ demanded Omar as Alim drew close.

‘My people,’ said Alim. ‘Tribesmen of the Mutrah.’

‘But you said they would kill you if you walked among them again.’

‘The family of the chief I duelled and killed are all dead now,’ said Alim. ‘Slain in another feud. There are new princes of the sands riding under the moon, men who remember me more kindly. I may return to their fold.’

‘You can’t leave, Alim. I am a freeman. Look. I have my papers.’

‘He finally recognized you?’ Alim sighed.

Omar stared in disbelief at the old nomad. ‘You knew?’

‘Any man too blind to look into Marid Barir’s face and see his eyes in yours could feel your back and know you for what you are from your lack of slave scars.’

‘I can still work with you, Alim. Not here, perhaps, but we can travel to the water farms down south. They are as short-staffed as we are after the plague. They will welcome two expert workers.’

‘I am called,’ said Alim. ‘This is my farm no longer. Wait here, boy. I will speak for you.’ He walked back up the hill and Omar watched the old nomad talking to the tribesmen and pointing back down the dunes towards Omar. The conversation became heated and Alim returned, followed by an old crone with a large hump on her back, bent to the side and filled with water – the result of womb magic. Perhaps her own? Is she a witch of Alim’s people?

‘I have spoken for you,’ said Alim. ‘But you may not come with us.’

‘Why would I want to come, Alim? My place is here in the empire – so is yours.’

The witch was shuffling about, looking at Omar from strange angles and he suspected her stance was not just simply due to the weight of water sloshing about her back. She is seeing into my blood, my very future.

‘Not with us,’ sang the witch. ‘He must not come with us. His path lies down a different line.’ She brushed Omar’s arm gently, then seemed to turn feral, spitting at his feet. ‘Filthy townsman.’

Omar watched the witch hobble back up the slope to the rest of the clan. ‘You would leave the House of Barir to follow that mad old crone?’