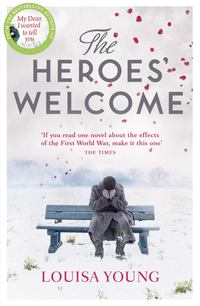

The Heroes’ Welcome

And that night, rattling in the separate couchettes, which gave an excuse for not thinking about that, for the moment, on the train to Paris, he couldn’t stop thinking about decisions, and the future, about how strange it was to be able to think about those things. There was going to be a future. He looked towards it, consciously, turning his mind away from the past the way a car’s lamps turn at a junction: illuminating possibilities, the road ahead, with beams of light that do not, cannot, show everything. As the car turns the lights are only ever shining straight on, out over – what? Another path, a path you won’t take and can’t know, that you glimpse in passing. It’s the future, it’s forward, but what forward entails, you can’t know. It’s shocking enough for now, after those years of orders and terror and imminent death, that forward even exists. He and Nadine had a forward to go into. They had choices. They had decisions to make. They had a degree of power. It was quite peculiar.

He was hideously aware of her, lying beneath him, separated by the padded wooden shelf he lay on, rattled and thrown around by the train.

Chapter Two

Locke Hill, Sidcup, March–April 1919

After the wedding Peter, Tom and Rose returned to Locke Hill. Max the red setter ran up, tail floating, and put his nose in Tom’s face. Tom stood on the drive while his father opened the front door; then he stood in the hall, by a jug of white jonquils, while Peter, tall, slender, still in his overcoat, hurried through to his study. He watched Julia, his mother, shimmy down the stairs and across the hall.

‘Darling!’ she cried, to Peter’s back. ‘It’s roast beef! What luxury! Will you eat with us? Or – I suppose you’re tired – Mrs Joyce has made Yorkshire pudding?’

She stopped at the dark, polished door of his study, which had fallen shut. All was silent.

‘I could bring your tray,’ she said. She was wearing lipstick. Tom watched her. He was nearly three years old and had been living with his grandmother and the nursemaid Margaret in another house; he didn’t know why. At Christmas he had been brought here; he didn’t know why. Now Eliza looked after him, and everything he wanted and needed was in the power of this Mummy and this Daddy, who he didn’t know, but who he understood were the important ones.

He went and stood by Julia, uncertainly.

‘Or if you prefer I could coddle you an egg …’ Julia called gaily, fresh and nervous. ‘Or …’ Her chalk-white face stretched immobile and expressionless, and her blue eyes shone, wide and terrified. Tom didn’t know why her face didn’t move the way other faces did.

The jonquils smelt beautiful. All winter Julia had been bringing up hyacinth bulbs in glass jars from the cellar – ‘heavenly smell, isn’t it?’ – or finding the first narcissi, or a sprig of early blossom from the orchard wall, and taking them in to Peter. Occasionally Tom, imitating her, would take a flower, and give it to Julia, or Nadine. They would say, ‘Thank you, darling.’

Nadine had not come back after the wedding. Tom had not known why she and Riley were living in his father’s house in the first place, any more than he knew why he had not been, or why Nadine and Riley had not come back. He did not know what the war was, nor how even if people had a home they did not always feel capable of going there. Of the webs that had bound these adults together over the past years he knew nothing. That his father had been Riley’s commanding officer; that Riley had carried his father back from No Man’s Land; that Rose had nursed Riley; that Riley had deserted Nadine; that Julia had comforted Nadine and offered her a home. He knew that they were tangled up with each other, but he knew only with a child’s aeonic instincts, not as information.

And he knew that though Julia was called Mummy and smelt right, she behaved wrong, and so it was best to go and sit with whoever was consistently kind. That was Nadine. He had liked to sit curled up against her, and when Riley came to sit there too, he didn’t make Tom go away.

Riley’s face had something in common with Julia’s, this much Tom saw, in that neither face moved with ease. But few faces were easy to read. His father’s eyes were pale and rich, grey-shadowed, with most to give and most to lose. They switched on and off like a lamp; you wanted their kind look, but you couldn’t trust it at all. Mrs Joyce, the cook-housekeeper, had an occasional expression of concentration it would be foolhardy to approach. Eliza, his nursemaid, had a sleepy, empty face. But his mother’s eyes lied like the tiny waves on the beach washing in four different directions, her skin made no sense, and her eyebrows were not made of hair but of tiny painted strokes which did not come off. He’d tried, once, with a hanky and lick, like his grandmother used to do to his cheeks when they were going somewhere. His mother had brushed him off. Nadine’s face was easiest: it had a warmth which Tom liked looking at. And so he was sad that she had not returned.

Julia’s sufferings during the war had been extreme, and exacerbated by the fact that from the outside they seemed the result of folly and vanity. Throughout those years she had tried to maintain her marriage by investing in the only thing about herself which had ever been valued by others: her blonde and luxuriant beauty. During that time Julia’s mother had taken Tom away, ‘for his own good’. By the end, lonely, neurotic, deserted, Julia had become unbalanced, and had inflicted on herself a misconceived chemical facial treatment, which she had deluded herself into believing would ensure her husband’s happiness. This had stripped and flayed her complexion into a scarlet fury, making it frightening and unreadable to a child – to her child, when he was brought back. He was scared of her, and she was scared of him. Now, by spring, her face had faded to a streaked waxy pallor. It was not unlike the make-up the girls in town were wearing, and the ghost of beauty appeared unreliably in her bones and in the smoothness. Meanwhile her painted mouth uttered the over-emphasised banalities with which she tried to make up for … everything. Her blue eyes shone wide and terrified. She had spent four years of war preparing for her husband’s return; four years of concentrated compacted nervous obsession with loveliness, comfort and order, for his benefit. She had utterly failed.

Even now she tried to give him treats all the time, like a cat dragging in dead bird after dead bird, laying them at the feet of an indifferent Caesar. The flowers. Dressing too smart for dinner at home. Snatching cushions out from behind his head to plump them up and make him ‘more comfortable’. He was not comfortable.

There was a fire in the sitting room. Tom went in there, and sat on the edge of the pale sofa where Riley and Nadine had usually sat. By habit he did not go on it, because he wanted it to be free for either of them. But they were gone now.

Until Christmas, when Riley and Peter had turned up unannounced in the middle of the night, Tom had not known any men. He was unaccustomed to affection, and at his grandmother’s house had sat quiet and dull with a wooden horse or a train, as instructed by whichever woman was in charge of him. When the grandmother had brought him to this house, and this father had appeared, at Christmas, Tom had felt a great and important slippage of relief inside himself: here it was, what had been missing. That the father periodically disappeared again, into the study, was not ideal, but Tom was a patient boy. The father was there. And Riley. Tom had lined up with these new people, the men, and Nadine, and Cousin Rose, as if they must be more reliable, kinder and stronger than the women he’d known so far. In this full house, he hoped he would find what had been missing.

Julia came in and held out her hand. Tom stood as he had been taught, and took it. She whispered down to him: ‘Come on, darling, let’s go and see if Daddy will come out and eat with us.’

Tom did not want to go. Daddy did not want anyone. That was why he had gone into his study. He didn’t know why Mummy didn’t understand something so simple. He wished Mummy would go behind her polished door, so that he, in the absence of Riley and Nadine, could go and sit in Max’s basket with him.

They approached the study. Julia smiled down at Tom as she knocked on the door. There was no response.

‘Well!’ she said and, almost shamed, she opened it.

Peter was sitting in his armchair, an old leathery thing, shiny with the polishing of ancestral buttocks in ancient tweed. He’d lit the lamp and was reading the paper, his long fingers holding the pages up and open. There was no fire, and the whisky glass beside him was already smeared.

‘Darling?’ she said.

‘Which darling?’ he said, not looking up.

‘You!’ she said. ‘Of course.’

‘Oh! I couldn’t tell. You call everybody darling.’ He moved the paper half an inch and glanced at her. ‘Well?’ he said, glittering.

She dropped Tom’s hand, and went away. The door swung shut behind her and so Tom stood there until Peter called him over, ruffled his white-blond hair and, finally, said, ‘Run along, old chap.’

Most days Julia worked herself up to try again.

‘Peter?’

A grunt.

‘There’s one thing I’ve been wondering about.’

A further, more defensive grunt.

‘It’s—’ from Julia, and at the same time from Peter: ‘Well, whatever it is, I’m sure it’s my fault.’

‘I wasn’t thinking about anything being … fault,’ she said.

Silence.

He had not looked up. It wasn’t the paper now, it was Homer. What might that mean? Why would he prefer to sit and read all day instead of being with us? Or going to the office like a proper man? It’s not as if he hasn’t read the Odyssey before …

His hair is looking thin.

He’s only thirty-three.

She let out a quick, exasperated sigh.

‘Peter darling, please listen to me.’

He turned, put down his book, looked up, and said, coldly and politely, with no tone of query in his voice, ‘What.’

Oh Peter!

‘I just want to know what happened!’ she burst out. ‘What happened to you?’

‘What happened?’ he said. He gave a little laugh of surprise. ‘Why, my dear, the Great War happened. Have you not heard about it? You might look it up. The Great War. The clue’s in the name. Now go away.’

She swallowed.

She still tuned his cello most days. He hadn’t looked at it since he’d been back. But he might.

He used to sing and make up little songs all the time. All the time! It was so sweet.

A few days later Julia knocked on Peter’s door again.

Go away, he thought. Go away.

‘What I was wondering,’ she said, loitering in his doorway, neither in nor out, ‘no, don’t say anything, please – I just … wanted to know what you thought.’

‘About?’ Peter said. He didn’t look up. Not out of unkindness, or lack of concern, but out of inability. Julia’s desperate goodwill tormented him – these constant interruptions – and then he was so foul to her – and her face – expressionless, taut, inhuman almost with those terribly human eyes glowing out – her face was a perpetual reproach. Look at her, he thought, though he couldn’t look at her.

‘I was wondering,’ she was saying, ‘about before the war …’

He raised his head and stared at her like a hyena about to howl.

‘Why on earth would you do that?’ he said.

‘I’m trying to remember whether we were ever happy.’

You want to remember happiness? Jesus Christ, woman, if one remembers happiness—

‘And whether my love for you is based on anything. I can’t remember. It’s been so long. I want to know. Because I think perhaps we were.’

Oh, God.

‘So what?’ he said, bewildered. ‘That’s the past. It’s dead.’ And – Ha! What a great big lie that is! he thought. If only it were dead. But it’s not even past. The past visited him most nights. Wandering about the wide gates and the hall of death, like Patroclus … She is no doubt thinking about some other past.

‘We were happy,’ she said, stubbornly. ‘We were happy in Venice, and we were happy that night at the Marsham-Townsends’, when we walked by the tennis court … my twenty-fifth birthday. And I was happy when you proposed to me …’

He lifted his mind. He had been thinking about the Trojan War; specifically about when mighty Achilles’ beloved friend Patroclus was killed in battle; about Achilles’ grief, how he locked himself away in his tent, went rather mad really, seeing ghosts and so on. He cut all his hair off, even though he’d promised it to a river god in exchange for a safe return home after the war. He’d refused to fight, though he was the greatest of the Greek heroes, and without him to lead them, the entire army lost faith, and every man in it was at risk. It was as if he no longer cared for his country, or for his leaders, or for his fellow soldiers – he only cared for his one friend. Peter had been thinking, is there an inherent contradiction in hating war and honouring soldiers? And then his mind had flung him back into thinking about soldiers. Dead ones. Loos and the Somme.

So with considerable effort, and for her sake, he lifted his mind from all that, and manoeuvred it round to Venice, and that night at the Marsham-Townsends’, and when he proposed to her. He remembered, for a moment, speaking to her appalling mother, and wondering what her father had been like. He tried to remember why he had proposed to her. Because we danced so well together – was that all? No. Because she was so beautiful? Yes – and … because she was so nice. She was soft, and gave kind advice. I was always pleased to see her when I turned up somewhere, and she was there. She was kind when my father died. All very straightforward, really. And I felt very tall with her on my arm.

All right, then. Yes, back in Arcadia, we were happy.

And at the thought of happiness, remembered happiness, his mind panicked and scattered: pure fear. He closed his eyes, clenched his mind, to hold on.

Hold on to your mind, he whispered to himself. Hold on. You’re tied to the mast. All right.

All right.

Now say something nice to the poor woman. Go on.

He couldn’t.

Julia tried to remember herself before she knew him. Desperate to please, obedient, bossed and squashed by her mother at every turn, her dear dad only a memory. She had realised the game early: the sweeter and prettier she was, the nicer people were to her.

And then there was Peter. How glad she had been to run to him, his amusement, his kindness.

To her, that night at the Marsham-Townsends’ sprang out, glistening with verisimilitude. She smelt the orange-flower water, saw the sheen of starch on the gentlemen’s shirt fronts, heard the waltz, felt the brush even of the palm-frond against her bare white shoulder and her skirts swirling at her ankles, as Peter wheeled her out on to the terrace, whispering – what had he whispered? Something mischievous.

Her mother had been delighted to give her to a man with a big house.

After they were married he’d said: ‘Let’s not have children immediately. Let’s run around and have some fun first.’ She had no idea there could be any choice – she’d known nothing about anything loving, about being on the same side with someone, and being happy together. Then suddenly there it was: she and Peter, together. Yes, happy!

He caught sight of her by the mirror in the hall. She was glancing at herself as he glanced at her. Her eyes fell away from her own taut reflection.

She did that, he thought, to her own face, to be more beautiful, because she thought I loved her for her beauty. She thought it would help. She thought that I, while fighting the bloody war, losing men, Atkins Lovall Bloom Jones oh stop it STOP IT – was most bothered by some idea that my beautiful wife was not beautiful enough. Somehow, apparently, evidently, I let her think that. Though, dear God, I do not understand why anybody would think that washing their face in carbolic acid was going to help anything. But – bad husband – I failed to protect her from this bizarre idiocy of her own. Just as I failed – bad soldier – to protect my men. Both at home and at the Front, I failed. And I wonder if anybody else on this earth can see that she is a casualty of that war just as much as Riley, or me …

The next time she came to lean against his door jamb, he got in first. He pulled his jacket around him, pursed his mouth against the shallow pattering of his heart, and said: ‘None of this is your fault.’

Think about her. Hold on to that. Poor Julia. Really. Poor tiresome bloody woman. ‘I don’t know why you put up with me,’ he said. And I don’t. You don’t have the first idea why I behave so bloody badly. ‘You’ve always done everything you should.’

He looked at her – eyes only, not turning his head – and he saw that she was, with a hopeless inevitability, taking these unexpected kind words at face value and investing them with huge meaning.

Oh, God.

She burst into tears.

Say something.

Not ‘fuck off’. Don’t say that.

‘Oh, Julia,’ he said, trying to buy time, to hold his mind, to make it all go away. ‘I think it’s probably too late for us. I’m an awful crock. But,’ – and here, desperate, he said the only thing which ever stopped her from looking so bloody tragic all the time – ‘I could perhaps not drink so much.’

‘I would like that,’ she said, and he saw the sudden whirling desperate hope erupting inside her. It filled him with despair.

Jesus Christ, Julia, he thought. I will never make you happy. You never will be happy! You’ve ruined your famous beauty, for me – poor fool! I’m a lush and no one else will want you. There is no chance for you now, shackled to me. And yet look at you, all hopeful – dear God, what a woman – let’s make you smile. Perhaps I can make you smile …

‘Well, I’ll give it a go,’ he said. ‘Perhaps I might – should I? Go to one of those places.’ I could do that. Could I? His heart was still going in that sick-making way – too quick and light, and all over the place.

‘Oh, please!’ she cried, too keenly. Clearly she had been about to say, ‘Oh no, of course not!’ when she thought: Yes! Grab the chance!

She’s awfully keen to be rid of me, he thought. And who can blame her?

And I’ve overdone it. I can’t do that.

But she was smiling at him, limp and tearful. ‘Oh, darling,’ she said, and corrected herself, quickly: ‘Oh, Peter.’

She looks happy. Dear God, I’ve made her happy! It’s so easy. But I can only do it by lying.

So lie. You owe her that.

Anyway, you lie to yourself all the time.

She was saying she would find someone, she would ask Rose, she was certain things could be better, she was so glad. She jumped up and went off to get on with it all.

Oh, Jesus.

In the course of the rest of the day he drank almost half a bottle of whisky and two bottles of wine. ‘Final fling,’ he said cheerfully. Julia beamed at him, the tight smile of her skin lit from within by a genuine if bewildered hope.

Keep away from me, he thought. Just keep away from me.

Chapter Three

Locke Hill, March–April 1919

To Rose it looked nothing like a fling. It looked like desperate unhappiness, i.e. business as usual.

The newlyweds heading off into eternal nuptial joy meant that Rose was now on her own with the two ghouls, the two fluttering, ragged banners gloriously emblazoned, in Rose’s eyes, with her failure to save them. Peter and Julia lurched through her days and tagged across her mind, united in bitterness, loss and the seeming impossibility of redemption. Frankly, Rose preferred being at work with Major Gillies at the Queen’s Hospital, looking after the facial injury patients. There at least the men were getting better, and moving on, or they were dying – but at least they were not stuck on a ghastly merry-go-round of their own making, with so little idea how they got on, and no idea how to get off. Not that I know any better, Rose thought. It’s just that I can see their every mistake – the ones they’ve made and the ones they’re still making.

Peter did not go somewhere. The idea of ‘going somewhere’ dissolved with the daylight: he would not go somewhere because, it turned out, the places he might go required him not to drink at all. He seemed to think alcohol was a balanced diet – untouched trays went in and out of the study, where he sat with the blind half down, reading his Homer. Rose would stick her head in, calling him old bean, trying to tempt him out with walnut cake (they had to chase every scrap of food into him), and minding so much that he didn’t seem to mind when she treated him like a schoolboy. And equally untouched trays went up and down the stairs to Julia, who went up to bed and stayed there, ‘resting’, later and later in the mornings, longer and longer hours, the room over-warm and the curtains half open, promising that she would really try, about the getting up. Oh the curtains – Millie the housemaid trying to open them, in the interests of fresh air and health and doing as Rose had instructed her, and Julia telling her not to, and Millie, disgruntled, leaving them hanging as nobody wanted them: half open, limp, unconvincing, unconvinced. Slatternly. Millie had been a pest ever since having to come back into service, after being sacked from Elliman’s for flirting with the foreman. It wasn’t Rose’s job to hire and fire, any more than it was to look after Peter and Julia – but when a vacuum develops in a household, someone like Rose, with her strong hands and her clear eyes, cannot help but fill it.

And into this dim stuffy room Eliza would take Tom, where Julia would cry on him, and make him lie down beside her, and stroke his head, and say: ‘Oh Tom, Tom, what is to become of you?’

Was it just that socks needed pulling up? Was it some kind of shock, some nerve condition? Were they ill, or not? Dr Tayle said rest, exercise, exercise, rest, fresh air, good food, rest … Dr Tayle seemed to think if Peter could be made to walk Max every day, everything would be all right. But Peter didn’t care for Max any more, and anyway Max was always curled up on Julia’s bed, adding to the fetid smell up there of hormones and old Malmaison, and leaving silky red hairs all over the silky orange cushions. Of course Peter was unhappy, but he wasn’t wounded – the limp from his leg wound from the Somme was hardly perceptible – and he didn’t seem to be sick. There were no particular signs of shell shock – so what was it?