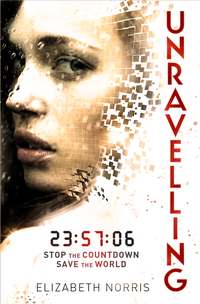

Unravelling

“Janelle?” she asks, fumbling with a foil packet of Advil. All the medication in our house now comes in single-serving packets. “Are you feeling better? Your father said you were sick.”

I nod. “I’m fine.” It’s possible he told her what happened with the truck and she forgot, or it’s possible he didn’t tell her at all. I’m not sure which is worse, but it doesn’t matter because the result is the same.

A quick glance at the broken glass in the sink—not on the floor and no blood—tells me she’s fine. The thin layer of dust covering the whole bathroom tells me I need to stop avoiding this room and get in here to clean this weekend.

“My head just hurts so much.” She throws a hand over her eyes to shield them from the light.

“Here, let me help you.” I’ve barely torn open the packet when she snatches the pills from my hand and swallows them dry. “Have you eaten anything today? Struz is bringing over Chinese food.”

“Great, the whole house will smell awful,” she says with a snort. “It’s like your father does this to me on purpose. He knows how terrible my headaches are and he knows how much strong smells bother me. And loud noises. I just need peace and quiet. I need to rest.”

I flick off the bathroom light and help her back to bed.

“I just need to rest,” she repeats as she gets under the covers. She looks small and fragile, like a sick child instead of my mother. “Can you get me a cold compress?”

Part of me wants to say, Get your own compress, but instead I nod.

Just because I died and had a moment of reflection doesn’t mean anything’s going to change around here.

It’ll take a lot more to wake this hollow heart.

I make eye contact with Alex, who’s been eating his second dinner with us every night since he was old enough to think up a good excuse to walk over to our house by himself—his mom cooks only organic, vegan, and gluten-free meals. He grins at me as he goes to take a sip of his Coke, but thinks better of it. Probably because he knows what’s coming. Struz has made us laugh until soda comes out of our noses many times.

Struz continues, “Jim! You gotta be kidding me. You mean you haven’t done a background check or a fingerprint analysis or anything on this Nick character?”

Jared laughs so hard he spits some of his Chinese food back onto his plate. Alex throws his napkin at Struz’s face. Dad and I shush them.

Struz dramatically wipes a hand through his hair and turns back to his captive audience. “That’s just not okay. I mean, seriously!” he continues, his voice quieter now, as he gestures to the flowers Nick brought earlier. “Jared! This guy brought J-baby roses! Pink ones! And we don’t even know who he is. What is wrong with your father?”

“Nick could be a terrorist,” Alex says. He finds that way too funny.

“He could be an alien!” Jared laughs.

I roll my eyes.

“No, seriously,” Dad says. “Let’s hear something about this guy. How did he win you over?”

Batting his eyes like a cartoon character, Alex says, “He’s dreamy,” with a dramatic sigh.

“That better not be an imitation of me,” I say.

Alex just laughs.

I look at Struz, who does his “give it to me” hand gesture, and then Dad, who also appears to be waiting for some kind of response. “Nick’s smart; he works hard.”

“At sports,” Alex coughs.

“Don’t be such an intellectual snob.”

“Seriously, Alex,” Struz says. “Professional athletes get a lot of play.”

I ignore that comment, since Dad and I haven’t really ever had the “who are you dating” conversation, and I’d prefer not to have it right now. And I’d really prefer not to talk about any of the guys in my life and how much “play” they are or aren’t getting. Struz included. “Nick wants to play football at USC next year,” I add, because something needs to be said.

“I suppose if he goes to USC, he’s good enough for me,” Struz says—not surprising, since that’s where he went to college. “But if he goes to UCLA, you have to break up.”

Jared laughs and announces that his lifelong dream is to go to UCLA, and I break open a fortune cookie. Stuffing the cookie into my mouth, I unroll the fortune and can’t help snorting a laugh.

Everyone pauses. “What’s it say?” Jared asks, reaching across the table.

Instead of answering, I flick the fortune to Alex before getting up. I grab my plate and a couple of empty cartons and head into the kitchen. Just before I turn the water on, I hear Alex’s voice reading my fortune. “Soon life will become more interesting.”

Jared’s unrestrained laughter drowns out what anyone else might be saying, and I’m glad.

I see those images of myself playing out again, watching my life pass me by. As if dying and then being resurrected weren’t enough—as if anything could become more interesting than that.

“Just not sure if interesting will be a good or a bad thing, huh?” Alex asks when he comes through the kitchen. He hands me the dirty dishes and opens the cabinet to grab some Tupperware. Struz did order the left side of the menu, and we’ll be eating Chinese for the next few days.

“I was dead, Alex,” I repeat, because we’ve had this conversation already. At least six times. In the hospital. Whenever Alex made it into my room without Jared or Nick.

“J,” Alex whispers, his hand falling on my arm, “I can’t imagine all the shit you’re feeling, but come on—you got hit by a truck, you lost consciousness, and you had seizures in the hospital.”

“One seizure.”

He pulls his hand back. “It wouldn’t be out of the ordinary for your mind to make something up. Besides, when’s the last time Ben Michaels and Elijah Palma even came to the beach?”

I can’t argue with that. I’m at the beach almost every day, and I can’t remember ever seeing them. Not that I would have been looking, though.

Logically, I know he’s right. I’ve heard the Near-Death Experience stories. People seeing angels, tunnels of light, balls of energy, even God. I don’t believe in that. I believe the mind is a powerful thing, and I believe people see what they want to see.

But why did I see Ben Michaels?

“J, did you hear what I said?”

“Hmm?”

Alex glances at the door to the dining room and lowers his voice as he sits on top of the counter and leans over my shoulder. “We should be asking about John Doe, his truck, and where the hell it came from.”

I found out some of the details at the hospital. After hitting me—if it even did—the truck crashed into an embankment and the driver—still unidentified, since the license in his wallet was a fake—died on impact.

Based on the skid marks and the collision, they’re betting he was flying down the hill at more than eighty miles an hour. It’s no wonder I didn’t see the truck coming.

But I still feel like an imposter—alive, when he’s not.

“Are you listening to me?”

“What? Sorry.” I turn off the water and dry my hands, making an attempt to give Alex my full attention.

“I was saying . . .” He draws it out, and I wave my hand to hurry him along. “I found out the truck that hit you, there’s no record of it. They couldn’t pull up the plates or the guy’s registration in the system—no record of any of them.”

“Wait, what was the fake name?”

Alex balks. “Does it matter?”

I don’t have a reason that I can explain. But it does matter.

“Don’t obsess over the unimportant stuff,” Alex says, and I nod because the last thing I want to do is get into an argument about my tendency to overanalyze and the way it drives Alex crazy. “Nothing he had on him matched anything in the DMV database.”

“What, so they’re all fake?”

Alex shrugs. “I don’t know. I only half heard the conversation your dad was having with the cops afterward, but when they ran the VIN and even the parts for the truck, nada.”

“That’s impossible. Even if somebody made fake plates and IDs—even if they stole parts from several trucks, the model numbers would still register. They’d just register to different vehicles.” I shake my head. “Who would go to the trouble for an old Toyota?”

“That’s the kicker,” Alex says, folding his arms across his chest and leaning against the kitchen counter. When he does that, he looks weirdly like my dad. “It’s not a Toyota.”

“Please, are we really going to have an argument about cars again? I thought we agreed you’d stick to calc and physics and leave practical knowledge to me.”

He smiles but doesn’t say anything. He knows something I don’t. And he’s dying to share. I wave for him to continue.

“The frame of the truck is the same design as a ’79 Toyota, but the engine and the vehicle paperwork, even the logo are all really different. It’s actually a 1997 Velociadad.”

“A what?” I turn back to the dishwasher. “I’ve never even heard of a car company anywhere in the world by that name.”

“Which is probably why I heard your dad ask if the truck appeared out of thin air,” Alex says.

I’m not even sure what I can say about that—what can anyone?

Alex is right, of course. This is more important than whether Ben Michaels resurrected me or I hallucinated it. This is real, and my dad is investigating it. That automatically gives it more urgency. It’s something I can handle now.

“Could someone be running a chop shop?” Alex asks. “Stealing vehicles, repackaging and reselling them as something else?”

“It’s possible, but why bother with all the hassle?”

Alex just shrugs and doesn’t say anything else, which means we’ve both reached our limit. Because I’m still pissed that he doesn’t believe that I died, I add, “No theories? C’mon, they don’t let just anyone into West Point.”

“Don’t say that out loud.” Alex looks around shiftily.

I roll my eyes. “Your mother hasn’t bugged my house as far as I know.”

“Your dad thinks I’ll be able to get in.” Of course Alex will get in. He has a 4.6 GPA and he’s bilingual. And my dad will write him a recommendation, since he went to West Point and graduated at the top of his class. Which is one of the reasons Alex wants to go.

Alex has gone silent, staring into space with his jaw set. I feel bad now for making him think about all the drama he’ll have to deal with when he finally admits to his mother he’s not going to graduate early and go to Stanford, thereby deviating from the life plan she’s been outlining for him since he was conceived.

“So which one of the boxes do you think has stuff about the truck in it?” I ask, because getting back to the investigation will be the only way to make him feel better—and because I know my dad has info about the truck. It doesn’t matter that the FBI doesn’t allow you to investigate anything that happens to you or your family or even people you know. My dad wouldn’t let a truck just appear out of thin air and hit me without investigating it.

“When I helped Jared bring them into the office, I set the lightest box in the back corner, farthest from his desk.” He doesn’t say anything else. He doesn’t need to. We’ve been spying on my dad and comparing notes about his cases practically forever. We’re nerds like that.

Except for the fact that the driver is dead, when it should have been me.

I roll out of bed and fumble into the hallway. We’ve lived here my whole life, and I’ve done the get-up-in-the-middle-ofthe-night stunt enough that I don’t need to turn on the lights. But I curse silently as I head down the stairs and see the sliver of light coming from my dad’s study. Either he and poor Struz are still working, or he’s fallen asleep at his desk.

I imagine it’s this way for all law-enforcement agents—long hours, sleepless nights, obsessive attention to detail, poring over case files. Every FBI agent I know has at least two cases they’ll never forget and never stop thinking about, investigations they’ll carry with them in the back of their minds always, for their entire lives. The one that went right. And the one that went wrong.

For my dad, the case that went right was the one that made his career.

It was more than ten years ago. It was his first case with Struz, who was a junior analyst at the time. I was too young to remember any of the details now, except the ones I heard repeated whenever he relived the story.

Ten Russian spies were discovered and arrested in Temecula, of all places. One was a Fox News reporter, popular with the public and, of course, beautiful. She ended up getting caught in a trap an undercover FBI agent set for her, and as a result all ten of them—and some guy bankrolling them in Budapest—went down. The undercover agent? My dad.

But the case that went wrong—the one still unsolved—is even older. It happened one of his first years on the job, before he got involved in counterintelligence. When my mom was pregnant with me—just after she’d found out I was a girl.

A seventeen-year-old girl—captain of the swim team, with an academic scholarship to USC, a boyfriend, friends, the perfect family, with a dog and white picket fence—went missing from her bedroom. All her possessions were untouched and in their rightful place. No forced entry, no signs of a break-in, no one heard or saw anything unusual—it was like she just . . . disappeared into thin air.

Except for a bloody partial handprint on her wall.

The files are all still on the corner of his desk. My dad reads them every night before he goes to sleep. If he even sleeps at all.

When I get to the bottom of the stairs and peek inside his office, it’s empty. The boxes are all over the place, some of them open, piles of papers laid out everywhere. My dad’s one of those visual/tactile learners. He’s got to lay everything out, move it around, and really study it, and then answers just come to him.

Obviously, he and Struz were working, and on an older case, something ongoing if it has this much of a paper trail, but everything looks like he just left it and went up to bed.

Which isn’t like him.

Although his oldest child did just come back from the dead. I suppose I could cut him some slack.

The “light” box that Alex strategically placed so I could snoop through it is one of the open ones. Only it doesn’t have anything to do with my truck or the driver. It’s an old case file from 1983, a series of deaths in California and Nevada, where the victims were killed from radiation poisoning. Deep gamma burns practically disfigured the bodies, most likely the result of some kind of nuclear exposure.

I leaf through the pages, scanning them for anything that might explain why these old files are in my dad’s study. Apparently, nothing other than the actual bodies had any kind of radiation residue—as if the bodies had been dumped somewhere else after exposure.

“All the nuclear plants nearby were searched, and nothing was found amiss.” I jump and drop the folders back into the box. “And the victims were never identified. Not even by dental records.”

When I turn around, my dad is leaning in the doorway to the office. He’s in sweatpants and an old army T-shirt—one that he doesn’t quite fill out the way he used to—his tattoos peeking out from under the sleeves. The lines in his face are starting to show, and his hair is starting to gray. He wears “tired” like an old friend.

“So they just stopped investigating?”

“I’ve got boxes full of theories and investigation notes,” he says with a shrug. “But they never found anything, and there were only three victims. After that, it seemed like just the Bureau’s presence stopped whatever was happening.”

This bothers me more than knowing that there are people out there who we know are guilty, but can’t prove it. This is more than just a flaw in the system. Because no one figured it out. These people died alone, and they’re the only ones who know how it happened—them and whoever was responsible. Someone else should know.

I’m about to say something when I see a photograph on top of a stack of papers on my dad’s desk. It looks like the body of a man—I think—and I can’t tell how old he is, because his body is so badly distorted by the radiation burns that he doesn’t even look human.

Nausea rolls through me. This photograph isn’t from the eighties. Based on the time stamp at the bottom corner, it’s from last week. Six days ago.

“Don’t ask,” my dad says before I can open my mouth. He moves farther into the room and flips over the photograph. “You know I can’t talk about active cases.”

The distorted image of the dead man in the photo is burned into my retinas, and I have to blink a few times to try to see something else. And that’s when I realize there was something else in the photograph—a set of numbers, written in marker on top of the picture. 29:21:33:21.

There are photos everywhere in this office. Reaching across the table, I grab a different one. This one is the body of a woman. The whole right side of her body is covered in burns that render her unrecognizable. The left side of her body looks pristine. It makes it even harder to look at her.

The numbers are there, though, in my dad’s handwriting. Written in black Sharpie in the top corner of the image. 44:14:38:44. I look back at the other set of numbers and the photograph of the dead man. The dates of the incidents on the time stamps are fifteen days apart. “It’s a countdown, but to what?”

A quick look of surprise flits across my dad’s face before he looks even-keeled again, and I know I’ve hit it right.

He shakes his head the way he does when he can’t figure something out.

“You’re counting down to something. I mean, what’s the end date?” Because that’s the bottom line—what’s important. Countdowns lead to something. What and when are the important questions to answer first. The how and why will come later.

He doesn’t answer. Not that I really expected him to. The fact that he hasn’t shooed me back upstairs to bed yet means he’s frustrated enough to forget the rules.

I set down the photograph and reach for one of the reports, skimming for numbers. I see them—46:05:49:21—and a reference to forty-six days only a sentence later. But I see something else too—UIED—before my dad remembers himself and pulls the report from my hand, placing it back on his desk.

“There’s something off about this one.” I have no idea what he means by “off.” He’s investigated thousands of cases, and there’s always one keeping him up at night.

But I know what UIED means—Unidentified Improvised Explosive Device.

How a countdown factors into a UIED is relatively easy to deduce. The countdown is a timer for some kind of explosive. But what it has to do with the bodies and the radiation is well beyond me.

“Where did you find an unidentified explosive device?” I ask. “Is it a bomb?” I grab the report back from him and flip through it.

“San Diego PD followed a lead and found it in an abandoned motel room after the first crime scene two months ago. They called in the bomb squad and us.”

“And?” But I’m still flipping through the report, and one line catches my eye.

So far all attempts to stop the countdown have been unsuccessful.

“This thing isn’t like anything I’ve ever seen,” my dad says, but it’s clear from his quiet, distant tone that he’s talking to himself. Then he sees the look on my face and adds, “The bodies and the UIED might not be connected,” but I can tell he doesn’t believe that.

I gesture to the countdown on the photographs. “You’re keeping track of how it relates to these deaths. How does it?” He must at least think it does, if he’s gone to the trouble to cross-reference them down to the second of the countdown. But even with my photographic memory and affinity for numbers, I don’t see an obvious connection. “Is there some kind of pattern?” If there is, I don’t see it.

My dad shakes his head, and for a minute I think he’s going to tell me—to say something else about the case. But instead he nods toward the door. “Go on, go back to bed.”

My skin itches—or rather, something underneath my skin itches—everywhere.

“You have to be exhausted, J-baby,” my dad says. “Don’t worry about this one. You know I’ll figure it out.”

I nod and leave the room, even though I’m not convinced the way I usually am.

I was exhausted. But now I’m not. Because I have the same feeling I did when I watched Ben Michaels ride his bike up Highway 101. Deep-seated conviction. A feeling of absolute certainty I couldn’t ignore even if I wanted to.

I glance at my watch and hope being resurrected from the dead didn’t affect my ability to do math in my head. Based on the time stamps of the photographs, we’re at twenty-one days, seventeen hours, thirty-nine minutes, seventeen seconds. And counting.

But the first person I see when I get out of Nick’s car in Eastview’s student lot is Ben Michaels.

He looks exactly like the Ben Michaels I would have pictured before: standing with a group of other nondescript stoners, all wearing similar dark hoodies and grungy, no-name-band T-shirts, most of them smoking something more than conventional cigarettes, some of them drinking something more than water from a water bottle. Elijah Palma and Reid Suitor stand in the center of the group; Ben’s on the outskirts, shoulders slumped and his hands buried deep in the pockets of his baggy jeans while he half leans against some rich kid’s SUV. I can’t see his eyes under the mess of dark brown curls, but I wonder if he’s staring back at me.

And I feel like my forehead—the exact spot where his cool lips brushed my skin—is on fire, and I have this crazy urge to reach up and somehow wipe his touch away.

“Janelle, c’mon!”

Jared and Nick are a car’s length away from me, walking toward the school. I shift my bag and follow them, ignoring Nick’s raised eyebrow and the flood of heat rushing to my face.

Just like I ignore the stares from half the senior class when Nick puts his arm around my shoulder and we walk through the front gate.