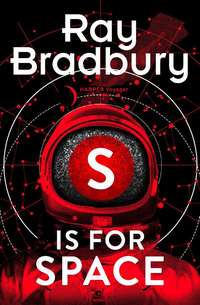

S is for Space

S IS FOR SPACE

Ray Bradbury

Dedication

For Charles Beaumont

who lived in that little house

halfway up in the next block

most of my life.

And for Bill Nolan

and Bill Idelson, friend of Rush Gook,

and for Paul Condylis …

Because …

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Chrysalis

Pillar of Fire

Zero Hour

The Man

Time in Thy Flight

The Pedestrian

Hail and Farewell

Invisible Boy

Come into My Cellar

The Million-Year Picnic

The Screaming Woman

The Smile

Dark They Were, and Golden-eyed

The Trolley

The Flying Machine

Icarus Montgolfier Wright

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Jules Verne was my father.

H. G. Wells was my wise uncle.

Edgar Allan Poe was the batwinged cousin we kept high in the back attic room.

Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers were my brothers and friends.

There you have my ancestry.

Adding, of course, the fact that in all probability Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein, was my mother.

With a family like that, how else could I have turned out than as I did: a writer of fantasy and most curious tales of science fiction.

I lived up in the trees with Tarzan a good part of my life with my hero Edgar Rice Burroughs. When I swung down out of the foliage I asked for a toy typewriter during my twelfth year, at Christmas. On this rattletrap machine I wrote my first John Carter, Warlord of Mars imitation sequels, and from memory tapped out whole episodes of Chandu the Magician.

I sent away boxtops and think I joined every secret radio society that existed. I saved comic strips, most of which I still have in great boxes down in my California basement. I went to movie matinees. I devoured the works of H. Rider Haggard and Robert Louis Stevenson. In the midst of my young summers I leapt high and dove deep down into the vast ocean of Space, long long before the Space Age itself was more than a fly speck on the two-hundred-inch Mount Palomar telescope.

In other words, I was in love with everything I did. My heart did not beat, it exploded. I did not warm toward a subject, I boiled over. I have always run fast and yelled loud about a list of great and magical things I knew I simply could not live without.

I was a beardless boy-magician who pulled irritable rabbits out of papier-mâché hats. I became a bearded man-magician who pulled rockets out of his typewriter and out of a Star Wilderness that stretched as far as eye and mind could see and imagine.

My enthusiasm stood me well over the years. I have never tired of the rockets and the stars. I never cease enjoying the good fun of scaring heck out of myself with some of my weirder, darker tales.

So here in this new collection of stories you will find not only S is for Space, but a series of subtitles that might well read: D is for Dark, or T is for Terrifying, or D is for Delight. Here you will find just about every side of my nature and my life that you might wish to discover. My ability to laugh out loud with the sheer discovery that I am alive in a strange, wild, and exhilarating world. My equally great ability to jump and raise up a crop of goosepimples when I smell strange mushrooms growing in my cellar at midnight, or hear a spider fiddling away at his tapestry-web in my closet just before sunrise.

You who read, and I who write, are very much the same. The young person locked away in me has dared to write these stories for your pleasure. We meet on the common ground of an uncommon Age, and share out our gifts of dark and light, good dream and bad, simple joy and not so simple sorrow.

The boy-magician speaks from another year. I stand aside and let him say what he most needs to say. I listen and enjoy.

I hope you will, too.

RAY BRADBURY

Los Angeles, California

December 1, 1965

Chrysalis

Rockwell didn’t like the room’s smell. Not so much McGuire’s odor of beer, or Hartley’s unwashed, tired smell—but the sharp insect tang rising from Smith’s cold green-skinned body lying stiffly naked on the table. There was also a smell of oil and grease from the nameless machinery gleaming in one corner of the small room.

The man Smith was a corpse. Irritated, Rockwell rose from his chair and packed his stethoscope. “I must get back to the hospital. War rush. You understand, Hartley. Smith’s been dead eight hours. If you want further information call a post-mortem—”

He stopped as Hartley raised a trembling, bony hand. Hartley gestured at the corpse—this corpse with brittle hard green shell grown solid over every inch of flesh. “Use your stethoscope again, Rockwell. Just once more. Please.”

Rockwell wanted to complain, but instead he sighed, sat down, and used the stethoscope. You have to treat fellow doctors politely. You press your stethoscope into cold green flesh, pretending to listen-

The small, dimly lit room exploded around him. Exploded in one green cold pulsing. It hit Rockwell’s ears like fists. It hit him. He saw his own fingers jerk over the recumbent corpse.

He heard a pulse.

Deep in the dark body the heart beat once. It sounded like an echo in fathoms of sea water.

Smith was dead, unbreathing, mummified. But at the core of that deadness—his heart lived. Lived, stirring like a small unborn baby!

Rockwell’s crisp surgeon’s fingers darted rapidly. He bent his head. In the light it was dark-haired, with flecks of gray in it. He had an even, level, nice-looking face. About thirty-five. He listened again and again, with sweat coming cold on his smooth cheeks. The pulse was not to be believed.

One heartbeat every thirty-five seconds.

Smith’s respiration—how could you believe that, too—one breath of air every four minutes. Lungcase movement imperceptible. Body temperature?

Sixty degrees.

Hartley laughed. It was not a pleasant laugh. More like an echo that had gotten lost. “He’s alive,” he said tiredly. “Yes, he is. He almost fooled me many times. I injected adrenalin to speed that pulse, but it was no use. He’s been this way for twelve weeks. And I couldn’t stand keeping him a secret any longer. That’s why I phoned you, Rockwell. He’s—unnatural.”

The impossibility of it overwhelmed Rockwell with an inexplicable excitement. He tried to lift Smith’s eyelids. He couldn’t. They were webbed with epidermis. So were the lips. So were the nostrils. There was no way for Smith to breathe—

“Yet, he’s breathing.” Rockwell’s voice was numb. He dropped his stethoscope blankly, picked it up, and saw his fingers shaking.

Hartley grew tall, emaciated, nervous over the table. “Smith didn’t like my calling you. I called anyway. Smith warned me not to. Just an hour ago.”

Rockwell’s eyes dilated into hot black circles. “How could he warn you? He can’t move.”

Hartley’s face, all razor-sharp bone, hard jaw, tight squinting gray eyes, twitched nervously. “Smith—thinks. I know his thoughts. He’s afraid you’ll expose him to the world. He hates me. Why? I want to kill him, that’s why. Here.” Hartley fumbled blindly for a blue-steel revolver in his rumpled, stained coat. “Murphy. Take this. Take it before I use it on Smith’s foul body!”

Murphy pulled back, his thick red face afraid. “Don’t like guns. You take it, Rockwell.”

Like a scalpel, Rockwell made his voice slash. “Put the gun away, Hartley. After three months tending one patient you’ve got a psychological blemish. Sleep’ll help that.” He licked his lips. “What sort of disease has Smith got?”

Hartley swayed. His mouth moved words out slowly. Falling asleep on his feet, Rockwell realized. “Not diseased,” Hartley managed to say. “Don’t know what. But I resent him, like a kid resents the birth of a new brother or sister. He’s wrong. Help me. Help me, will you?”

“Of course.” Rockwell smiled. “My desert sanitarium’s the place to check him over, good. Why—why Smith’s the most incredible medical phenomenon in history. Bodies just don’t act this way!”

He got no further. Hartley had his gun pointed right at Rockwell’s stomach. “Wait. Wait. You—you’re not going to bury Smith? I thought you’d help me. Smith’s not healthy. I want him killed! He’s dangerous! I know he is!”

Rockwell blinked. Hartley was obviously psychoneurotic. Didn’t know what he was saying. Rockwell straightened his shoulders, feeling cool and calm inside. “Shoot Smith and I’ll turn you in for murder. You’re overworked mentally and physically. Put the gun away.”

They stared at one another.

Rockwell walked forward quietly and took the gun, patted Hartley understandingly on the shoulder, and gave the weapon to Murphy, who looked at as if it would bite him. “Call the hospital, Murphy. I’m taking a week off. Maybe longer. Tell them I’m doing research at the sanitarium.”

A scowl formed in the red fat flesh of Murphy’s face. “What do I do with this gun?”

Hartley shut his teeth together, hard. “Keep it. You’ll want to use it—later.”

Rockwell wanted to shout it to the world that he was sole possessor of the most incredible human in history. The sun was bright in the desert sanitarium room where Smith lay, not saying a word, on his table; his handsome face frozen into a green, passionless expression.

Rockwell walked into the room quietly. He used the stethoscope on the green chest. It scraped, making the noise of metal tapping a beetle’s carapace.

McGuire stood by, eyeing the body dubiously, smelling of several recently acquired beers.

Rockwell listened intently. “The ambulance ride may have jolted him. No use taking a chance—”

Rockwell cried out.

Heavily, McGuire lumbered to his side. “What’s wrong?”

“Wrong?” Rockwell stared about in desperation. He made one hand into a fist. “Smith’s dying!”

“How do you know? Hartley said Smith plays possum. He’s fooled you again—”

“No!” Rockwell worked furiously over the body, injecting drugs. Any drugs. All drugs. Swearing at the top of his voice. After all this trouble, he couldn’t lose Smith. No, not now.

Shaking, jarring, twisting deep down inside, going completely liquidly mad, Smith’s body sounded like dim volcanic tides bursting.

Rockwell fought to remain calm. Smith was a case unto himself. Normal treatment did nothing for him. What then? What?

Rockwell stared. Sunlight gleamed on Smith’s hard flesh. Hot sunlight. It flashed, glinting off the stethoscope tip. The sun. As he watched, clouds shifted across the sky outside, taking the sun away. The room darkened. Smith’s body shook into silence. The volcanic tides died.

“McGuire! Pull the blinds! Before the sun comes back!”

McGuire obeyed.

Smith’s heart slowed down to its sluggish, infrequent breathing.

“Sunlight’s bad for Smith. It counteracts something. I don’t know what or why, but it’s not good—” Rockwell relaxed. “Lord, I wouldn’t want to lose Smith. Not for anything. He’s different, making his own standards, doing things men have never done. Know something, Murphy?”

“What?”

“Smith’s not in agony. He’s not dying either. He wouldn’t be better off dead, no matter what Hartley says. Last night as I arranged Smith on the stretcher, readying him for his trip to this sanitarium, I realized, suddenly, that Smith likes me.”

“Gah. First Hartley. Now you. Did Smith tell you that?”

“He didn’t tell me. But he’s not unconscious under all that hard skin. He’s aware. Yes, that’s it. He’s aware.”

“Pure and simple—he’s petrifying. He’ll die. It’s been weeks since he was fed. Hartley said so. Hartley fed him intravenously until the skin toughened so a needle couldn’t poke through it.”

Whining, the cubicle door swung slowly open. Rockwell started. Hartley, his sharp face relaxed after hours of sleep, his eyes still a bitter gray, hostile, stood tall in the door. “If you’ll leave the room,” he said, quietly, “I’ll destroy Smith in a very few seconds. Well?”

“Don’t come a step closer.” Rockwell walked, feeling irritation, to Hartley’s side. “Every time you visit, you’ll have to be searched. Frankly, I don’t trust you.” There were no weapons. “Why didn’t you tell me about the sunlight?”

“Eh?” Soft and slow Hartley said it. “Oh—yes. I forgot. I tried shifting Smith weeks ago. Sunlight struck him and he began really dying. Naturally, I stopped trying to move him. Smith seemed to know what was coming, vaguely. Perhaps he planned it; I’m not sure. While he was still able to talk and eat ravenously, before his body stiffened completely, he warned me not to move him for a twelve-week period. Said he didn’t like the sun. Said it would spoil things. I thought he was joking. He wasn’t. He ate like an animal, a hungry, wild animal, fell into a coma, and here he is—” Hartley swore under his breath. “I’d rather hoped you’d leave him in the sun long enough to kill him inadvertently.”

McGuire shifted his two hundred fifty pounds. “Look here, now. What if we catch Smith’s disease?”

Hartley looked at the body, his pupils shrinking. “Smith’s not diseased. Don’t you recognize degeneration when you see it? It’s like cancer. You don’t catch it, you inherit a tendency. I didn’t begin to fear and hate Smith until a week ago when I discovered he was breathing and existing and thriving with his nostrils and mouth sealed. It can’t happen. It mustn’t happen.”

McGuire’s voice trembled. “What if you and I and Rockwell all turn green and a plague sweeps the country—what then?”

“Then,” replied Rockwell, “if I’m wrong, perhaps I am, I’ll die. But it doesn’t worry me in the least.”

He turned back to Smith and went on with his work.

A bell. A bell. Two bells, two bells. A dozen bells, a hundred bells. Ten thousand and a million clangorous, hammering, metal dinning bells. All born at once in the silence, squalling, screaming, hurting echoes, bruising ears!

Ringing, chanting with loud and soft, tenor and bass, low and high voices. Great-armed clappers knocking the shells and ripping air with the thrusting din of sound!

With all those bells ringing, Smith could not immediately know where he was. He knew that he could not see, because his eyelids were sealed tight, knew he could not speak because his lips had grown together. His ears were clamped shut, but the bells hammered nevertheless.

He could not see. But yes, yes, he could, and it was like inside a small dark red cavern, as if his eyes were turned inward upon his skull. And Smith tried to twist his tongue, and suddenly, trying to scream, he knew his tongue was gone, that the place where it used to be was vacant, an itching spot that wanted a tongue but couldn’t have it just now.

No tongue. Strange. Why? Smith tried to stop the bells. They ceased, blessing him with a silence that wrapped him up in a cold blanket. Things were happening. Happening.

Smith tried to twitch a finger, but he had no control. A foot, a leg, a toe, his head, everything. Nothing moved. Torso, limbs—immovable, frozen in a concrete coffin.

A moment later came the dread discovery that he was no longer breathing. Not with his lungs, anyway.

“BECAUSE I HAVE NO LUNGS!” he screamed. Inwardly he screamed and that mental scream was drowned, webbed, clotted, and journeyed drowsily down in a red, dark tide. A red drowsy tide that sleepily swathed the scream, garroted it, took it all away, making Smith rest easier.

I am not afraid, he thought. I understand that which I do not understand. I understand that I do not fear, yet know not the reason.

No tongue, no nose, no lungs.

But they would come later. Yes, they would. Things were—happening.

Through the pores of his shelled body air slid, like rain needling each portion of him, giving life. Breathing through a billion gills, breathing oxygen and nitrogen and hydrogen and carbon dioxide, and using it all. Wondering. Was his heart still beating?

But yes, it was beating. Slow, slow, slow. A red dim susurrance, a flood, a river surging around him, slow, slower, slower. So nice.

So restful.

The jigsaw pieces fitted together faster as the days drifted into weeks. McGuire helped. A retired surgeon-medico, he’d been Rockwell’s secretary for a number of years. Not much help, but good company.

Rockwell noted that McGuire joked gruffly about Smith, nervously; and a lot. Trying to be calm. But one day McGuire stopped, thought it over, and drawled, “Hey, it just came to me! Smith’s alive. He should be dead. But he’s alive. Good God!”

Rockwell laughed. “What in blazes do you think I’m working on? I’m bringing an X-ray machine out next week so I can find out what’s going on inside Smith’s shell.” Rockwell jabbed with a hypo needle. It broke on the hard shell.

Rockwell tried another needle, and another, until finally he punctured, drew blood, and placed the slides under the microscope for study. Hours later he calmly shoved a serum test under McGuire’s red nose, and spoke quickly.

“Lord, I can’t believe it. His blood’s germicidal. I dropped a streptococci colony into it and the strep was annihilated in eight seconds! You could inject every known disease into Smith and he’d destroy them all, thrive on them!”

It was only a matter of hours until other discoveries. It kept Rockwell sleepless, tossing at night, wondering, theorizing the titanic ideas over and over. For instance—

Hartley’d fed Smith so many cc’s of blood-food every day of his illness until recently. NONE OF THAT FOOD HAD EVER BEEN ELIMINATED. All of it had been stored, not in bulk-fats, but in a perfectly abnormal solution, an x-liquid contained in high concentrate form in Smith’s blood. An ounce of it would keep a man well fed for three days. This x-liquid circulated through the body until it was actually needed, when it was seized upon and used. More serviceable than fat. Much more!

Rockwell glowed with his discovery. Smith had enough x-liquid stored in him to last months and months more. Self-sustaining.

McGuire, when told, contemplated his paunch sadly.

“I wish I stored my food that way.”

That wasn’t all. Smith needed little air. What air he had he seemed to acquire by an osmotic process through his skin. And he used every molecule of it. No waste.

“And,” finished Rockwell, “eventually Smith’s heart might even take vacations from beating, entirely!”

“Then he’d be dead,” said McGuire.

“To you and I, yes. To Smith—maybe. Just maybe. Think of it, McGuire. Collectively, in Smith, we have a self-purifying blood stream demanding no replenishment but an interior one for months, having little breakdown and no elimination of wastes whatsoever because every molecule is utilized, self-evolving, and fatal to any and all microbic life. All this, and Hartley speaks of degeneration!”

Hartley was irritated when he heard of the discoveries. But he still insisted that Smith was degenerating. Dangerous.

McGuire tossed his two cents in. “How do we know that this isn’t some super-microscopic disease that annihilates all other bacteria while it works on its victim. After all—malarial fever is sometimes used surgically to cure syphilis; why not a new bacillus that conquers all?”

“Good point,” said Rockwell. “But we’re not sick, are we?”

“It may have to incubate in our bodies.”

“A typical old-fashioned doctor’s response. No matter what happens to a man, he’s ‘sick’—if he varies from the norm. That’s your idea, Hartley,” declared Rockwell, “not mine. Doctors aren’t satisfied unless they diagnose and label each case. Well, I think that Smith’s healthy; so healthy you’re afraid of him.”

“You’re crazy,” said McGuire.

“Maybe. But I don’t think Smith needs medical interference. He’s working out his own salvation. You believe he’s degenerating. I say he’s growing.”

“Look at Smith’s skin,” complained McGuire.

“Sheep in wolf’s clothing. Outside, the hard, brittle epidermis. Inside, ordered regrowth, change. Why? I’m on the verge of knowing. These changes inside Smith are so violent that they need a shell to protect their action. And as for you, Hartley, answer me truthfully, when you were young, were you afraid of insects, spiders, things like that?”

“Yes.”

“There you are. A phobia. A phobia you use against Smith. That explains your distaste for Smith’s change.”

In the following weeks, Rockwell went back over Smith’s life carefully. He visited the electronics lab where Smith had been employed and fallen ill. He probed the room where Smith had spent the first weeks of his “illness” with Hartley in attendance. He examined the machinery there. Something about radiations …

While he was away from the sanitarium, Rockwell locked Smith tightly, and had McGuire guard the door in case Hartley got any unusual ideas.

The details of Smith’s twenty-three years were simple. He had worked for five years in the electronics lab, experimenting. He had never been seriously sick in his life.

And as the days went by Rockwell took long walks in the dry-wash near the sanitarium, alone. It gave him time to think and solidify the incredible theory that was becoming a unit in his brain.

And one afternoon he paused by a night-blooming jasmine outside the sanitarium, reached up, smiling, and plucked a dark shining object off of a high branch. He looked at the object and tucked it in his pocket. Then he walked into the sanitarium.

He summoned McGuire in off the veranda. McGuire came. Hartley trailed behind, threatening, complaining. The three of them sat in the living quarters of the building.

Rockwell told them.

“Smith’s not diseased. Germs can’t live in him. He’s not inhabited by banshees or weird monsters who’ve ‘taken over’ his body. I mention this to show I’ve left no stone untouched. I reject all normal diagnoses of Smith. I offer the most important, the most easily accepted possibility of—delayed hereditary mutation.”

“Mutation?” McGuire’s voice was funny.

Rockwell held up the shiny dark object in the light.

“I found this on a bush in the garden. It’ll illustrate my theory to perfection. After studying Smith’s symptoms, examining his laboratory, and considering several of these”—he twirled the dark object in his fingers—“I’m certain. It’s metamorphosis. It’s regeneration, change, mutation after birth. Here. Catch. This is Smith.”

He tossed the object to Hartley. Hartley caught it.

“This is the chrysalis of a caterpillar,” said Hartley.

Rockwell nodded. “Yes, it is.”

“You don’t mean to infer that Smith’s a—chrysalis?”

“I’m positive of it,” replied Rockwell.

Rockwell stood over Smith’s body in the darkness of evening. Hartly and McGuire sat across the patient’s room, quiet, listening. Rockwell touched Smith softly. “Suppose that there’s more to life than just being born, living seventy years, and dying. Suppose there’s one more great step up in man’s existence, and Smith has been the first of us to make that step.