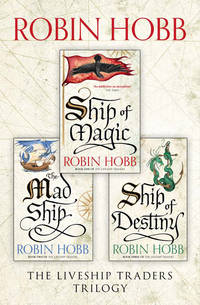

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Kennit allowed Gankis to demonstrate it for him twice. Then, without a word, he extended a long-fingered hand towards him gracefully, and the sailor set the treasure in his palm. Kennit held his bemused smile firmly as he first lifted the ball to the sunlight, and then set the tumblers within to dancing for himself. The ball did not quite fill his hand. ‘A child’s plaything,’ he surmised loftily.

‘If the child were the richest prince in the world,’ Gankis dared to observe. ‘It’s too fragile a thing to give a kid to play with, sir. All it would take would be dropping it once…’

‘Yet it seems to have survived bobbing about in the waves of a storm, and then being flung up on a beach,’ Kennit pointed out with measured good nature.

‘That’s true, sir, that’s true, but then this is the Treasure Beach. Almost everything cast up here is whole, from what I’ve heard tell. It’s part of the magic of this place.’

‘Magic’ Kennit permitted himself a slightly wider smile as he placed the orb in the roomy pocket of his indigo jacket. ‘So you believe it is magic that sweeps such trinkets up on this shore, do you?’

‘What else, captain? By all rights, that should have been smashed to bits, or at least scoured by the sands. Yet it looks as if it just come out of a jeweller’s shop.’

Kennit shook his head sadly. ‘Magic? No, Gankis, no more magic than the rip-tides in the Orte Shallows, or the Spice Current that speeds sailing ships on their journeys to the islands and taunts them all the way back. It’s but a trick of wind and current and tides. No more than that. The same trick that promises that any ship that tries to anchor off this side of the island will find herself beached and broken before the next tide.’

‘Yessir,’ Gankis agreed dutifully, but without conviction. His traitorous eyes strayed to the pocket where Captain Kennit had stowed the glass ball. Kennit’s smile might have deepened fractionally.

‘Well? Don’t loiter here. Get back up there and walk the bank and see what else you find.’

‘Yessir,’ Gankis conceded, and with one final regretful glance at the pocket, the older man turned and hastened back to the bank. Kennit slipped his hand into his pocket and caressed the smooth cold glass there. He resumed his stroll down the beach. Overhead gulls followed his example, sliding slowly down the wind as they searched the retreating waves for titbits. He did not hasten, but kept in mind that on the other side of the island his ship was awaiting him in treacherous waters. He’d walk the whole length of the beach, as tradition decreed, but he had no intention of lingering after he had heard the sooth-saying of an Other. Nor did he have any intention of leaving whatever treasure he found. A true smile tugged at the corner of his mouth.

As he strolled, he took his hand from his pocket and absently touched his opposite wrist. Concealed by the lacy cuff of his white silk shirt was a fine double thong of black leather. It bound a small wooden trinket tightly to his wrist. The ornament was a carved face, pierced at the brow and lower jaw so the face would be snugged firmly against his wrist, exactly over his pulse point. At one time, the face had been painted black, but most of that was worn away now. The features still stood out distinctly; a tiny mocking face, carved with exquisite care. Its visage was twin to his own. It had cost him an inordinate amount of coin to commission it. Not everyone who could carve wizardwood would, even if they had the balls to steal some.

Kennit remembered well the artisan who had worked the tiny face for him. He’d sat for long hours in the man’s studio, washed in the cool morning light as the artist painstakingly worked the iron-hard wood to reflect Kennit’s features. They had not spoken. The artist could not. The pirate did not. The carver had needed absolute silence for his concentration, for he worked not only wood but a spell that would bind the charm to protect the wearer from enchantments. Kennit had had nothing to say to him anyway. The pirate had paid him an exorbitant advance months ago, and waited until the artist had sent him a messenger to say that he had obtained some of the precious and jealously-guarded wood. Kennit had been outraged when the artist had demanded still more money before he would begin the carving and spell-setting, but Kennit had only smiled his small sardonic smile, and put coins and jewels and silver and gold links on the artist’s scales until the man had nodded that his price had been met. Like many in Bingtown’s illicit trades, he had long ago sacrificed his own tongue to ensure his client’s privacy. While Kennit was not convinced of the efficacy of such a mutilation, he appreciated the sentiment it implied. So when the artist was finished and had personally bound the ornament to Kennit’s wrist, the man had only been able to nod vehemently his extreme satisfaction with his own skill as he touched the wood with avid fingertips.

Afterwards Kennit had killed him. It was the only sensible thing to do, and Kennit was an eminently sensible man. He had taken back the extra fee the man had demanded. Kennit could not abide a man who would not honour his original bargain. But that had not been the reason he’d killed him. He’d killed him for the sake of keeping the secret. If men knew that Captain Kennit wore a charm to ward off enchantments, why, then they would believe that he feared them. He could not let his crew believe that he feared anything. His good luck was legendary. All the men who followed him believed in it, most more strongly than Kennit himself did. It was why they followed him. They must not ever think that he feared anything could threaten that luck.

In the year since he had killed the artist, he had wondered if killing him had somehow harmed the charm, for it had not quickened. When he had originally asked the carver how long it would take for the little face to come to life, the man had shrugged eloquently, and indicated with much hand fluttering that neither he nor anyone else could predict such a thing. For a year Kennit had waited for the charm to quicken, to be sure that its spell was completely activated. But there had come a time when he could not wait any longer. He had known, on an instinctive level, that it was time for him to visit the Treasure Beach and see what fortune the ocean would wash up for him. He could wait no longer for the charm to awaken; he’d decided to take his chances. He’d have to once more trust his good luck to protect him, as it always had. It had protected him the day he’d had to kill the artist, hadn’t it? The man had turned unexpectedly, just in time to see Kennit drawing his blade. Kennit was convinced that if the man had had a tongue in his head, his scream would have been much louder.

Kennit set the artist firmly out of his mind. This was no time to be thinking of him. He hadn’t come to the Treasure Beach to dwell on the past, but to find treasure to secure his future. He fixed his eyes on the undulating tide line and followed it down the beach. He ignored the glistening shells, the crab claws and tangles of uprooted seaweed, and driftwood large and small. His pale blue eyes searched for jetsam and wreckage only. He did not have to go far to be rewarded. In a small battered wooden chest, he found a set of teacups. He did not think men had made them nor used them. There were twelve of them and they were made of hollowed-out ends of birds’ bones. Tiny blue pictures had been painted on them, the lines so fine that it looked as if the brush had been a single hair. The cups were well used. The blue pictures were faded beyond recognition of their original form and the carved bone handles were worn thin with use. He tucked the small case in the crook of his arm and walked on.

He strode along under the sun and against the wind, his fine boots leaving clean tracks in the wet sand. Occasionally he lifted his gaze, casually, to scan the entire beach. He did not let his expectations show on his face. When he let his gaze drop to the sand, he discovered a tiny cedar box. Saltwater had warped the wood. To open it he had to strike it on a rock like a nut. Inside were fingernails. They were fashioned of mother-of-pearl. Minute clamps would affix them on top of an ordinary nail and in the tip of each one was a tiny hollow, perhaps to store poison. There were twelve of them. Kennit put them into his other pocket. They rattled together as he walked.

It did not distress him that what he had found was obviously neither of human make nor designed for human use. Although he had earlier mocked Gankis’s belief in the magic of the beach, all knew that more than one ocean’s waves brushed these rocky shores. Ships foolish enough to anchor anywhere off of this island during a squall were likely to disappear entirely, leaving not even a splinter of wreckage. Old sailors said they had been swept clean out of this world and into the seas of another one. Kennit did not doubt it. He glanced at the sky, but it remained clean and blue. The wind was crisp, but he had faith the weather would hold so that he could walk the Treasure Beach and then hike back across the island to where his ship waited at anchor in Deception Cove. He trusted his luck to hold.

His most unsettling discovery came next. It was a bag made of red and blue leather stitched together, half-buried in the wet sand. The leather was stout, the bag meant to last. Saltwater had soaked and stained it, bleeding the colours into one another. The brine had seized up the brass buckles that had secured it and stiffened the leather straps that went through them. He used his knife to rip open a seam. Inside was a litter of kittens, perfectly formed with long claws and iridescent patches behind their ears. They were dead, all six of them. Quelling his distaste, he picked up the smallest. He turned the limp body over in his hands. It was blue-furred, a deep periwinkle blue with pink-lidded eyes. Small. The runt most likely. It was sodden and cold and disgusting. A ruby earring like a fat tick decorated one of the wet ears. He longed to simply drop it. Ridiculous. He plucked the earring free and dropped it in his pocket. Then, moved by an impulse he did not understand, he returned the small blue bodies to the bag and left it beside the tide line. Kennit walked on.

Awe flowed through him with his blood. Tree. Bark and sap, the scent of the wood and the leaves fluttering overhead. Tree. But also the soil and the water, the air and the light, all was coming and going through the being known as tree. He moved with them, sliding in and out of an existence of bark and leaf and root, air and water.

‘Wintrow.’

The boy lifted his eyes slowly from the tree before him. With an effort of will, he focused his gaze on the smiling face of the young priest. Berandol nodded in encouragement. Wintrow closed his eyes for an instant, held his breath, and pulled himself free of his task. When he opened his eyes, he took a sudden breath as if breaking clear of deep water. Dappling light, sweet water, soft wind all faded abruptly. He was in the monastery work room, a cool hall walled and floored with stone. His bare feet were chill against the floor. There were a dozen other slab tables in the big room. At three others, boys like himself worked slowly, their dreamlike movements indicative of their tranced state. One wove a basket and two others shaped clay with wet grey hands.

He looked down at the pieces of gleaming glass and lead on the table before him. The beauty of the stained-glass image he had pieced together astonished even him, yet it still could not touch the wonder of having been the tree. He touched it with his fingers, tracing the trunk and the graceful branches. Caressing the image was like touching his own body; he knew it that well. Behind him he heard the soft intake of Berandol’s breath. In his state of still-heightened awareness, he could feel the priest’s awe flowing with his own, and for a time they stood quietly, glorying together in the wonder of Sa.

‘Wintrow,’ the priest repeated softly. He reached out and traced with a finger the tiny dragon that peered from the tree’s upper branches, then touched the glistening curve of a serpent’s body, all but hidden in the twisting roots. He put a hand on the boy’s shoulders and turned him gently away from his worktable. As he steered him from the work room, he rebuked him gently. ‘You are too young to sustain such a state for the whole morning. You must learn to pace yourself.’

Wintrow lifted his hands to knuckle at eyes that were suddenly sandy. ‘I’ve been in there all morning?’ he asked dazedly. ‘It did not seem like it, Berandol.’

‘I am sure it did not. Yet I am sure the weariness you feel now will convince you it is so. One must be careful, Wintrow. Tomorrow, ask a watcher to stir you at mid-morning. Talent such as you possess is too precious to allow you to burn it out.’

‘I do ache, now,’ Wintrow conceded. He ran his hand over his brow, pushing fine black hair from his eyes and smiled. ‘But the tree was worth it, Berandol.’

Berandol nodded slowly. ‘In more ways than one. The sale of such a window will yield enough coin to re-roof the noviciates’ hall. If Mother Dellity can bring herself to let the monastery part with such a thing of wonder.’ He hesitated a moment, then added, ‘I see they appeared again. The dragon and the serpent. You still have no idea…’ he let his voice trail away questioningly.

‘I do not even have a recollection of putting them there,’ Wintrow said.

‘Well.’ There was no trace of judgement in Berandol’s voice. Only patience.

For a time they walked in companionable silence through the cool stone hallways of the monastery. Slowly Wintrow’s senses lost their edge and faded to a normal level. He could no longer taste the scents of the salts trapped in the stone walls, nor hear the minute settling of the ancient blocks of stone. The rough brown bure of his novice robes became bearable against his skin. By the time they reached the great wooden door and stepped out into the monastery gardens, he was safely back in his body. He felt groggy as if he had just awakened from a long sleep, yet as bone-weary as if he had hoed potatoes all day. He walked silently beside Berandol as monastery custom dictated. They passed others, some men and women robed in the green of full priesthood and others dressed in white as acolytes. Greetings were exchanged as nods.

As they neared the tool shed, he felt a sudden unsettling certainty that they were going there and that he would spend the rest of the afternoon working in the sunny garden. At any other time, it might have been a pleasant thing to look forward to, but his recent efforts in the dim work room had left his eyes sensitive to light. Berandol glanced back at his lagging step.

‘Wintrow,’ he chided softly. ‘Refuse the anxiety. When you borrow trouble against what might be, you neglect the moment you have now to enjoy. The man who worries about what will next be happening to him loses this moment in dread of the next, and poisons the next with pre-judgement.’ Berandol’s voice took on an edge of hardness. ‘You indulge in pre-judgement too often. If you are refused the priesthood, it will most like be for that.’

Wintrow’s eyes flashed to Berandol’s in horror. For a moment stark desolation dominated his face. Then he saw the trap. His face broke into a grin, and Berandol’s answered it when the boy said, ‘But if I fret about it, I shall have pre-judged myself to failure.’

Berandol gave the slender boy a good-natured shove with his elbow. ‘Exactly. Ah, you grow and learn so fast. I was much older than you, twenty at least, before I learned to apply that Contradiction to daily life.’

Wintrow shrugged sheepishly. ‘I was meditating on it last night before I fell asleep. “One must plan for the future and anticipate the future without fearing the future.” The Twenty-Seventh Contradiction of Sa.’

‘Thirteen years old is very young to have reached the Twenty-Seventh Contradiction,’ Berandol observed.

‘What one are you on?’ Wintrow asked artlessly.

‘The Thirty-Third. The same one I’ve been on for the last two years.’

Wintrow gave a small shrug of his shoulders. ‘I haven’t studied that far yet.’ They walked in the shade of apple trees, under leaves hanging limp in the heat of the day. Ripening fruit weighted the boughs. At the other end of the orchard, acolytes moved in patterns through the trees, bearing buckets of water from the stream.

‘“A priest should not presume to judge unless he can judge as Sa does; with absolute justice and absolute mercy”.’ Berandol shook his head. ‘I confess, I do not see how that is possible.’

The boy’s eyes were already turned inward, with only the slightest line to his brow. ‘As long as you believe it is impossible, you close your mind to understanding it.’ His voice seemed far away. ‘Unless, of course, that is what we are meant to discover. That as priests we cannot judge, for we have not the absolute mercy and absolute justice to do so. Perhaps we are only meant to forgive and give solace.’

Berandol shook his head. ‘In the space of a few moments, you slice through as much of the knot as I had done in six months. But then I look about me, and I see many priests who do judge. The Wanderers of our order do little except resolve differences for folk. So they must have somehow mastered the Thirty-Third Contradiction.’

The boy looked up at him curiously. He opened his mouth to speak and then blushed and shut it again.

Berandol glanced down at his charge. ‘Whatever it is, go ahead and say it. I will not rebuke you.’

‘The problem is, I was about to rebuke you,’ Wintrow confessed. The boy’s face brightened as he added, ‘But I stopped myself before I did.’

‘And you were going to say to me?’ Berandol pressed. When the boy shook his head, his tutor laughed aloud. ‘Come, Wintrow, having asked you to speak your thought, do you think I would be so unfair as to take offence at your words? What was in your mind?’

‘I was going to tell you that you should govern your behaviour by the precepts of Sa, not by what you see others doing.’ The boy spoke forthrightly, but then lowered his eyes. ‘I know it is not my place to remind you of that.’

Berandol looked too deep in thought to have taken offence. ‘But if I follow the precept alone, and my heart tells me it is impossible for a man to judge as Sa does, with absolute justice and absolute mercy, then I must conclude…’ His words slowed as if the thought came reluctantly. ‘I must conclude that either the Wanderers have much greater spiritual depth than I. Or that they have no more right to judge than I do.’ His eyes wandered among the apple trees. ‘Could it be that an entire branch of our order exists without righteousness? Is not it disloyal even to think such a thing?’ His troubled glance came back to the boy at his side.

Wintrow smiled serenely. ‘If a man’s thoughts follow the precepts of Sa, they cannot go astray.’

‘I shall have to think more on this,’ Berandol concluded with a sigh. He gave Wintrow a look of genuine fondness. ‘I bless the day you were given me as student, though in truth I often wonder who is student and who is teacher here. I shall miss you.’

Sudden alarm filled Wintrow’s eyes. ‘Miss me? Are you leaving, have you been called to duty so soon?’

‘Not I. I should have given you this news better, but as always your words have led my thoughts far from their starting point. I am not leaving, but you. It was why I came to find you today, to bid you pack, for you are called home. Your grandmother and mother have sent word that they fear your grandfather is dying. They would have you near at such a time.’ At the look of devastation on the boy’s face, Berandol added, ‘I am sorry to have told you so bluntly. You so seldom speak of your family. I did not realize you were close to your grandfather.’

‘I am not,’ Wintrow simply admitted. ‘Truth to tell, I scarcely know him. When I was small, he was always at sea. At the times when he was home, he always terrified me. Not with cruelty, but with… power. Everything about him seemed too large for the room, from his voice to his beard. Even when I was small and overheard other folk talking about him, it was as if they spoke of a legend or a hero. I don’t recall that I ever called him Grandpa, nor even Grandfather. When he came home, he’d blow through the house like the north wind and mostly I took shelter from his presence rather than enjoyed it. When I was dragged out before him, all I can recall was that he found fault with my growth. “Why is the boy so puny?” he’d demand. “He looks just like my boys, but half the size! Don’t you feed him meat? Doesn’t he eat well?” Then he would pull me near and feel my arm, as if I were being fattened for the table. I always felt ashamed of my size, then, as if it were a fault. Since I was given over to the priesthood, I have seen even less of him, but my impression of him has not changed. Still, it is not my grandfather I dread, nor even keeping his death watch. It’s going home, Berandol. It is so… noisy.’

Berandol grimaced in sympathy.

‘I don’t believe I even learned to think until I came here,’ Wintrow continued. ‘There, it was too noisy and too busy. I never had time to think. From the time Nana rousted us out of bed in the morning until we were bathed, gowned and dumped back in bed at night, we were in motion. Being dressed and taken on outings, having lessons and meals, visiting friends, being dressed differently and having more meals… it was endless. You know, when I first got here, I didn’t leave my cell for the first two days. Without Nana or Grandma or Mother chasing me about, I had no idea what to do with myself. And for so long, my sister and I had been a unit. “The children” need their nap, “the children” need their lunch. I felt I’d lost half my body when they separated us.’

Berandol was grinning in appreciation. ‘So that is what it is like, to be a Vestrit. I’d always wondered how the children of the Old Traders of Bingtown lived. For me, it was very different, and yet much the same. We were swineherds, my family. I had no nanny or outings, but there were always chores aplenty to keep one busy. Looking back, we spent most of our time simply surviving. Stretching out the food, fixing things long past fixing by anyone else’s standards, caring for the swine… I think the pigs received better care than anyone else. There was never even a thought of giving up a child for the priesthood. Then my mother became ill, and my father made a promise that if she lived, he would dedicate one of his children to Sa. So when she lived, they sent me off. I was the runt of the litter, so to speak. The youngest surviving child, and with a stunted arm. It was a sacrifice for them, I am sure, but not as great as giving up one of my strapping older brothers.’

‘A stunted arm?’ Wintrow asked in surprise.

‘It was. I’d fallen on it when I was small, and it was a long time healing, and when it did heal, it was never as strong as it should have been. But the priests cured me. They put me with the watering crew on the orchard, and the priest in charge of us gave me mismatched buckets. He made me carry the heavier one with my weaker arm. I thought he was a madman at first; my parents had always taught me to use my stronger arm for everything. It was my earliest introduction to Sa’s precepts.’

Wintrow frowned to himself for a moment, then grinned. ‘“For the weakest has but to try his strength to find it, and then he shall be strong”.’

‘Exactly.’ The priest gestured at the long low building before them. The acolytes’ cells had been their destination. ‘The messenger was delayed getting here. You will have to pack swiftly and set out right away if you are to reach port before your ship sails. It’s a long walk.’

‘A ship!’ The desolation that had faded briefly from Wintrow’s face flooded back. ‘I hadn’t thought of that. I hate travelling by sea. But when one must go from Jamaillia to Bingtown, there is no other choice.’ His frown deepened. ‘Walk to port? Didn’t they arrange a man and a horse for me?’

‘Do you so quickly revive to the comforts of wealth, Wintrow?’ Berandol chided him. When the boy hung his head, abashed, he went on, ‘No, the message said that a friend had offered you passage across and the family had been glad to accept it.’ More gently he added, ‘I suspect that money is not so plentiful for your family as it once was. The Northern War has hurt many of the trading families, both in the goods that never came down the Buck River and those that never were sold there.’ More pensively, he went on, ‘And our young Satrap does not favour Bingtown as his father and grandfathers did. They seemed to feel that those brave enough to settle the Cursed Shores should share generously in the treasures they found there. But not young Cosgo. It is said that he feels they have reaped the reward of their risk-taking long enough, that the Shores are well settled and whatever curse was once there is now dispersed. He has not only sent them new taxes but has parcelled out new grants of land near Bingtown to some of his favourites.’ Berandol shook his head. ‘He breaks the word of his ancestor, and causes hardship for folk who have always kept their word with him. No good can come of this.’