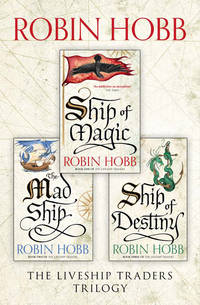

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

‘They come,’ Vivacia said softly.

‘I know.’ He gave a nervous giggle, chilling to hear. ‘I feel them. Through you.’

It was his first acknowledgement of such a thing. Vivacia wished it could have come at a different time, when they could have spoken about it privately, or simply been alone together to explore the joining. But the two men were on the foredeck and Wintrow reflexively surged to his feet and turned to face them. His injured hand rested upon the palm of his good one like an offering.

Kyle jerked his chin toward his son. ‘Boy thinks you need to take his finger off. What do you think?’

Wintrow’s heart seemed to pause in his chest, then begin again. Wordlessly he presented his hand to the mate. Gantry glanced at it and bared his teeth in his distaste. ‘The boy is right.’ He spoke to his captain, not Wintrow. He gripped Wintrow’s right wrist firmly and turned his hand to see the finger from all sides. He gave a short grunt of disgust. ‘I’ll be having a word with Torg. I should have seen this hand before now. Even if we take the finger off now, the lad will need a day or so of rest, for it looks to me like the poison from the finger has worked into the hand.’

‘Torg knows his business,’ Kyle replied. ‘No man can predict everything.’

Gantry looked levelly at his captain. There was no argument in his voice as he observed, ‘But Torg has a mean streak to him, and it comes out worst when he thinks he has one who should be his better at his mercy. It’s what drove Brashen away; the man was a good hand, save when Torg was prodding him. Torg, he picks a man, and doesn’t know when to leave off riding him.’ Gantry went on carefully, ‘It’s not a matter of favouritism. Don’t fear that. I don’t care what this lad’s name is, sir. He’s a working hand aboard the ship, and a ship runs best when all hands can work.’ He paused. ‘I’ll be having a word with Torg,’ he repeated, and this time Kyle made no reply. Gantry’s next words were to Wintrow.

‘You’re ready to do this.’ It wasn’t really a question, mostly an affirmation that the boy had seen the right of it.

‘I am.’ Wintrow’s voice had gone low and deep. He went down on one knee, almost as if he were pledging his loyalty to someone, and set his injured hand flat on Vivacia’s deck. She closed her eyes. She concentrated on that touch, on the splayed fingers pressing against the foredeck. She was wordlessly grateful that the foredeck was planked with wizardwood. It was almost an unheard-of use for the expensive wood, but today she would see that it would be worth every coin the Vestrits had pledged for it. She gripped his hand, adding her will to his that it would not move from the place where he had set it.

The mate had crouched beside him and was unrolling a canvas kit of tools. Knives and probes rested in canvas pockets, while needles were pierced through the canvas. Some were ready threaded with fine fish-gut twine. As the last of the kit bounced open, it revealed the saws, toothed both fine and coarse. Wintrow swallowed. Beside them Gantry set out bandages of lint and linen.

‘You’ll want brandy,’ Gantry told him harshly. The man’s heart was a deep trembling inside him. Vivacia was glad he was not unfeeling about this.

‘No.’ The boy’s word was soft.

‘He may want it. Afterwards.’ She dared to speak up. Wintrow did not contradict her.

‘I’ll fetch it,’ Kyle said harshly.

‘No.’ Both she and Wintrow spoke the word together.

‘I wish you to stay,’ Vivacia said more softly. It was her right. But in case Kyle did not understand it, she spoke it aloud. ‘When you cut Wintrow, I bleed. In a manner of speaking,’ she added. She forced her own nervousness down. ‘I have a right to demand that you be here, with me, when something as unsettling as this is happening on my deck.’

‘We could take the boy below,’ Kyle offered gruffly.

‘No,’ she forbade him again. ‘If this mutilation must be done, I wish it done here, where I may witness it.’ She saw no need to tell him that no matter where on the ship it was done, she would be aware of it. If he was that ignorant of her full nature, let him remain so. ‘Send one of the others.’

Kyle turned to follow her gaze, and almost startled. The rumour had spread quickly. Every hand that was not occupied had somehow found an excuse to draw closer to the foredeck. Mild, white-faced, almost jumped out of his skin when Kyle pointed at him. ‘You. Fetch the brandy and a glass. Quickly.’

The boy jumped to the command, his bare feet slapping the deck as he hastened away. No one else moved. Kyle chose to ignore them.

Wintrow took a deep breath. If he had noticed those who had gathered to watch, he gave no sign of it. His words were spoken to Gantry. He lifted his left hand and pointed carefully to his injured right. ‘There is a place, right here… in the knuckle. That’s where I want you to cut. You’ll have to go in… with the point of the knife… and sort of feel as you cut. If you feel the knuckle of your own hand, you can find the spot I mean. That way there will be no jag of bone left… And afterwards, I want you to draw the skin together over the… space. And stitch it.’ He cleared his throat and spoke plainly. ‘Careful is better than fast. A clean slice, not a chop.’

Between each phrase, Wintrow drew a steadying breath. His voice did not quite shake, nor did his hand as he pointed carefully to what had been the index finger of his right hand. The finger that might have worn a priest’s pledge ring some day, had he been allowed to keep it. Sa, in your mercy, do not let me scream. Do not let me faint, nor look away. If I must do this, let me do it well.

The undercurrent of the boy’s thoughts were so strong, Vivacia found herself joined with him. He took a final breath, deep and steadying as Gantry chose a knife and held it up. It was a good one, shining and clean and sharp. Wintrow nodded slowly. Behind him came the patter of Mild’s feet and his whisper of, ‘I’ve brought the brandy, sir,’ but it seemed to come from far away, as faint and meaningless as the cries of the sea-birds. Wintrow was doing something, Vivacia realized. With each breath, the muscles of his body slackened. He dwindled inside himself, going smaller and stiller, almost as if he were dying. He’s going to faint, she thought, and pity for him filled her.

Then in the next instant he did something she did not understand. He left himself. He was not gone from his body, but in some strange way he was apart from it. It was almost as if he had joined her and looked through her eyes at the slender boy kneeling so still upon the foredeck. His hair had pulled free from his sailor’s queue. A few strands danced on his forehead, others stuck to it with sweat. But his black eyes were calm, his mouth relaxed as he watched the shining blade come down to his hand.

Somewhere there was great pain, but Wintrow and Vivacia watched the mate lean on the blade to force it into the boy’s flesh. Bright red blood welled. Clean blood, Wintrow observed somewhere. The colour is good, a thick deep red. But he spoke no word and the sound of the mate swallowing as he worked was almost as loud as the shuddering breath Kyle drew in as the blade sank deep into the boy’s knuckle. Gantry was good at this; the fine point of the blade slipped into the splice of the joint. As it severed it, Wintrow could feel the sound it made. It was a white pain, shooting up his finger bone, travelling swift and hot through his arm and into his spine. Ignore it, he commanded himself savagely. In a willing of strength unlike anything Vivacia had ever witnessed before, he kept the muscles of his arm slack. He did not allow himself to flinch or pull away. His only concession was to grip hard the wrist of his right hand with his left, as if he could strangle the coursing of the pain up his arm. Blood flowed freely now, puddling between his thumb and middle finger. It felt hot on Vivacia’s planking. It soaked into the wizardwood and she drew it in, cherishing this closeness, the salt and copper of it.

The mate was true to Wintrow’s wishes. There was a tiny crunch as the last gristle parted under the pressure of the blade, and then he drew the knife carefully across to sever the last bit of skin. The finger rested on her deck now, a separate thing, a piece of meat. Wintrow reached down carefully with his left hand to pick up his own severed finger and set it aside. With the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, he pinched the skin together over the place where his right forefinger had been.

‘Stitch it shut,’ he told the mate calmly as his own blood welled and dripped. ‘Not too tight; just enough to hold the skin together without the thread cutting into it. Your smallest needle and the finest gut you have.’

Wintrow’s father coughed and turned away. He walked stiffly to the railing, to stand and stare out at the passing islands as if they held some deep and sudden fascination for him. Wintrow appeared not to notice, but Gantry darted a single glance at his captain. Then he folded his lips, swallowed hard himself, and took up the needle. The boy held his own flesh together as the mate stitched it and knotted the gut thread. Wintrow set his bloodied left hand flat to the deck, bracing himself as the mate bandaged the place where the finger had been. And the whole time he gave no sign, by word or movement, that he felt any pain at all. He might have been patching canvas, Vivacia thought. No. He was aware, somewhere, of the pain. His body was aware, for the sweat had flowed down the channel of his spine and his shirt was mired in it, clinging to him. He felt the pain, somewhere, but he had disconnected his mind from it. It had become only his body’s insistent signal to him that something was wrong, just as hunger or thirst was a signal. A signal that one could ignore when one must.

Oh. I see. She did not, quite, but was moved at what he was sharing with her. When the bandaging was done, he rocked back on his heels but was wise enough not to try to stand. No sense in tempting fate right now. He had come too far to spoil it with a faint. Instead he took the cup of brandy that Mild poured for him with shaking hands. He drank it down in three slow swallows, not tossing it back but drinking as one drank water when very thirsty. The glass was bloodied with his fingerprints when he handed it back to Mild.

He looked around himself. Slowly he called his awareness back into his body. He clenched his teeth against the white wave of pain from his hand. Black dots swam for an instant before his eyes. He blinked them away, focusing for a time on the two bloody handprints he had left on Vivacia’s deck. The blood had soaked deep into the wizardwood. They both knew that no amount of sanding would ever erase those twin marks. Slowly he lifted his gaze and looked around. Gantry was cleaning the knife on a rag. He returned the boy’s gaze, his brow furrowed but a small smile on his face. He gave him the smallest of nods. Mild’s face was still pale, his eyes huge. Kyle gazed out over the rail.

‘I’m not a coward.’ He didn’t speak loud, but his voice carried. His father turned slowly to the challenging words. ‘I’m not a coward,’ Wintrow repeated more loudly. ‘I’m not big. I don’t claim to be strong. But I’m neither a weakling nor a coward. I can accept pain. When it’s necessary.’

A strange odd light had come into Kyle’s eyes. The beginnings of a smile hovered at the corners of his mouth. ‘You are a Haven,’ he pointed out with quiet pride.

Wintrow met his gaze. There was neither defiance nor the will to injure, but the words were clear. ‘I’m a Vestrit.’ He looked down to the bloody handprints on Vivacia’s deck, to the severed forefinger that still rested there. ‘You’ve made me a Vestrit.’ He smiled without joy or mirth. ‘What did my grandmother say to me? “Blood will tell”. Yes.’ He stooped to the deck and picked up his own severed finger. He considered it carefully for a moment, then held it out to his father. ‘This finger will never wear a priest’s signet,’ he said. To some he might have sounded drunken, but to Vivacia his voice was broken with sorrow. ‘Will you take it, sir? As a token of your victory?’

Captain Kyle’s fair face darkened with the blood of anger. Vivacia suspected he was close to hating his own flesh and blood at that moment. Wintrow stepped lightly toward him, a very strange light in his eyes. Vivacia tried to understand what was happening to the boy. Something was changing inside him, an uncoiling of strength was filling him. He met his father’s gaze squarely, yet in his own voice was nothing of anger, nor even pain as he stepped forward boldly, to a place close enough to invite his father to strike him. Or embrace him.

But Kyle Haven moved not at all. His stillness was a denial, of all the boy was, of all he did. Wintrow knew in that instant that he would never please his father, that his father had never even desired to be pleased by him. He had only wanted to master him. And now he knew he would not.

‘No, sir? Ah, well.’ With a casualness that could not have been faked, Wintrow walked to the bow of the ship. For a moment he made a show of studying the finger he held in his hand. The nail, torn and dirtied in his work, the mangled flesh and crushed bone of it. Then he flipped the small piece of flesh overboard as if it were nothing at all, had never been connected to him in any way. There he remained, not leaning on the railing but standing straight beside her. He looked far ahead to a distant horizon. To a future he had been promised that now seemed far further than days or distance could make it. He swayed very slightly on his feet. No one else moved or spoke. Even the captain was still, his eyes fastened to his son as if their gaze could pierce him. Cords of muscle stood out on his neck.

Gantry spoke. ‘Mild. Take him below. See him to his berth. Check on him at each bell. Come to me if he runs a high fever or is delirious.’ He rolled up his tools and tied the canvas round them. He opened a wooden case and sorted through some bottles and packets in it. He did not even look up as he added quietly, ‘You others should find your duties before I find them for you.’

It was enough of a threat. The men dispersed. His words had been simple, the commands well within the range of his duties as mate. But no one could miss that in a very evasive way, Gantry had come between the captain and his son. He had done it as smoothly as he might for any other man aboard who had brought himself too sharply to the captain’s attention. It was not an unheard of thing for the mate to do; he’d done it often enough before when Kyle had first taken over the Vivacia. But never before had he interfered between the captain and his son. That he had done so now marked his acceptance of Wintrow as a genuine member of the crew, rather than as the captain’s spoiled son, brought along for the sake of his discipline.

Mild made himself small and unnoticed as he waited. After a time, Captain Kyle turned without a word and stalked aft. Mild watched him go for a time, then jerked his eyes away, as if it were somehow shameful to watch his captain retreat to his own quarters.

‘And Mild,’ Gantry suddenly went on, as if there had been no pause. ‘Assist Wintrow in moving his gear and bedding to the forecastle. He’ll bunk with the rest of the men. Once he’s settled, give him this. No more than a spoonful and bring the rest back to me right away. It’s laudanum,’ he added, raising his voice for Wintrow’s benefit. ‘I want him to sleep. It’ll speed the healing.’ He handed the boy the fat brown bottle, then rose and tucked the rest of his supplies under his arm. With no more than that, Gantry turned and walked away.

‘Yessir,’ Mild agreed. He moved up shyly to Wintrow’s side. When the other boy did not deign to notice him, he nerved himself to tug at Wintrow’s sleeve. ‘You heard what the mate said,’ he reminded him awkwardly.

‘I’d rather stay here.’ Wintrow’s voice had gone drifting and dreamy. The pain, Vivacia realized, must be paid for sooner or later. He had kept his body from reacting to it at the time, but the price now was complete exhaustion.

‘I know,’ Mild said, almost kindly. ‘But it was an order.’

Wintrow sighed heavily and turned. ‘I know.’ With the docility of weariness, he followed the other boy below.

A short time later Vivacia was aware that Gantry had gone back to take the wheel himself. It was something he did when he was disturbed and wanted time to think. He was not, she thought to herself, a bad mate. Brashen had been better, but Brashen had been with her longer. His touch on the wheel was sure and steady, reassuring but not distrustful of her.

She looked down furtively and opened her hand. The finger lay in her palm. She did not think anyone had seen her catch it. She could not have explained why she had done so, save that it had been a part of Wintrow, and she was unwilling to lose even so small a fragment of him. It was so tiny compared to her own larger-than-life digits. A thin, jointed rod of bone, coated with flesh and skin, and at the end of it, the finely-ridged nail. Even crushed and bloody, it fascinated her with its delicacy and detail. She compared it to her own hand. Her carver had done a competent job, with her joints and nails and even the tendons on the back of her hand. But there was no fine pattern of follicles on the back of her fingers, no tiny hairs, no whorling prints on the pads of her fingers. She bore, she decided regretfully, only a passing resemblance to a true creature of flesh and blood.

For a time longer she examined her treasure. Then she glanced furtively aft before she lifted it to her lips. She could not throw it away and she had no place to keep it, save one. She placed it in her mouth and swallowed. It tasted like his blood had smelled; of salts and copper and in an odd way, like the sea itself. She swallowed it down, to become part of herself. She wondered what would become of it, deep inside her wizardwood gullet. Then she felt it being absorbed, in much the same way the deck-planks had soaked up his blood.

She had never eaten anything meat before. She had never known hunger or thirst. Yet in the taking of Wintrow’s severed flesh into herself, she satisfied some longing that had gone nameless before. ‘We are one, now,’ she whispered to herself.

In a bunk in the forecastle, Wintrow turned over restlessly. The laudanum could soften but not still the throbbing in his hand. His flesh felt hot and dry, tight over the bones of his face and arm. ‘To be one with Sa,’ he said in a small cracked voice. The priest’s ultimate goal. ‘I shall be one with Sa,’ he repeated more firmly. ‘It is my destiny.’

Vivacia had not the heart to contradict him.

It was raining, the relentless pelting rain that was the hallmark of winter in Bingtown. It ran down his carved locks and dripped from his beard onto his bare chest. Paragon crossed his arms on his chest, and then shook his head, sending heavy drops flying. Cold. Cold was mostly something he remembered from sensations humans had stored for him. Wood cannot get cold, he told himself. I’m not cold. No. It was not a matter of temperature, it was just the annoying sensation of water trickling over him. He wiped a hand over his brow and shook the water from it.

‘I thought you said it was dead.’ A husky contralto voice spoke unnervingly near him. That was another problem with rain; the sound of it filled his ears, numbing them to important sounds like footsteps on wet sand.

‘Who’s there?’ he demanded. His voice sounded angry. Anger was a better thing to show humans than fear. Fear only made them bolder.

No one replied. He hadn’t expected anyone to answer, really. They could see that he was blind. They’d probably creep about and he’d never know where they were until the rock hit. He put all his concentration into listening for stealthy footsteps. But when the second voice spoke, it was not far from where the first had originated. He recognized it right away by the Jamaillian accent. Mingsley.

‘I thought it was. It never moved nor spoke at all the last time I was here. Dav — my intermediary assured me that it was alive still, but I doubted him. Well. This puts a whole new slant on this.’ He cleared his throat. ‘The Ludlucks have been reluctant to deal, and now I see why. I thought I was bidding on dead wood. My offer was far too low. I shall have to approach them again.’

‘I think I’ve changed my mind.’ The woman’s voice was low. Paragon couldn’t decide what emotion she was repressing. Disgust? Fear? He could not be sure. ‘I don’t think I want anything to do with this.’

‘But you seemed so intrigued earlier,’ Mingsley objected. ‘Don’t be squeamish now. So the figurehead is alive. That only increases our possibilities.’

‘I am intrigued by wizardwood,’ she admitted reluctantly. ‘Someone brought me a tiny piece to work on once. The customer wanted me to carve it into the shape of a bird. I told him, as I tell you, that the work I do is determined by the wood I am given, not by any whim of my own or the customers. The man urged me to try. But when I took the wood from him, it felt… evil. If you could steep wood with an emotion, I’d say that one was pure malice. I couldn’t bear to even touch it, let alone carve it. I told him to take it away.’

Mingsley chuckled as if the woman had told an amusing story. ‘I’ve found,’ he said loftily, as if speaking in generalities, ‘that the finely-tuned sensibilities of an artist are best soothed with the lovely sound of coins being stacked. I am sure we can get past your reservations. And I can promise you that the money from this would be incredible. Look at what your work brings in now, using ordinary wood. If you fashioned beads from wizardwood, we could ask… whatever we wanted. Literally. What we would be offering buyers has never been available to them before. We’re two of a kind in this. Outsiders, seeing what all the insiders have missed.’

‘Two of a kind? I am not at all sure we can even talk.’ There was no compromise to the woman’s tone, but Mingsley seemed deaf to it.

‘Look at it,’ he gloated. ‘Fine straight grain. Silvery colour. Plank after plank and I haven’t spotted a single knot. Not one! Wood like that, you can do anything with it. Even if we remove the figurehead, have you restore it, and sell it separately, there is still enough wizardwood in this hulk to found an industry. Not just your beads and charms; we have to think bigger than that. Chairs and bedsteads and tables, all elaborately carved. Ah! Cradles. Imagine the status of that, rocking your first-born to sleep in a cradle all carved from wizardwood. Or,’ the man’s voice suddenly grew even more enthused, ‘perhaps you might carve the headboard of the cradle with women’s faces. We could find out how to quicken them, teach them to sing lullabies, and we’d have a cradle that could sing a child to sleep!’

‘The thought makes my blood cold,’ the woman said.

‘You fear this wood then?’ Mingsley gave a short bark of laughter. ‘Don’t succumb to Bingtown superstition.’

‘I don’t fear wood,’ the woman snapped back. ‘I fear people like you. You charge into things blindly. Stop and think. The Bingtown Traders are the most astute merchants and traders this part of the world has ever seen. There must be a reason why they do not traffic in this wood. You’ve seen for yourself that the figurehead lives. But you don’t ask how or why! You simply want to make tables and chairs of the same substance. And finally, you stand before a living being and blithely speak of chopping up his body to make furniture.’

Mingsley made an odd sound. ‘We have no real assurances that this is a live being,’ he said tolerantly. ‘So it moved and it spoke. Once. Jumping jacks on sticks move, as do puppets on strings. Parrots talk. Shall we give them all the status of a human?’ His tone was amused.

‘And now you are willing to spout whatever nonsense you must to get me to do your will. I’ve been down to the North wall where the liveships tie up. As have you, I’ll wager. The ships I saw there are clearly alive, clearly individuals. Mingsley. You can lie to yourself and convince yourself of anything you wish. But don’t expect me to accept your excuses and half-truths as reasons I should work for you. No. I was intrigued when you told me there was a dead liveship here, one whose wood could be salvaged. But even that was a lie. There is no point to me standing out here in the rain with you any longer. I’ve decided this is wrong. I won’t do it.’