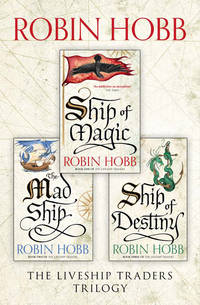

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Shocked, she opened her mouth, but no words came. He reached the cold, cold water and plunged one bare foot and leg into it. ‘Sa preserve me,’ he gasped, and then resolutely lowered himself into the water. She heard him catch his breath hoarsely in its chill embrace. Then he let go of the chain and paddled awkwardly away. His tied bundle bobbed in his wake. He swam like a dog.

Wintrow, she screamed. Wintrow, Wintrow, Wintrow. Soundless screams, waterless tears. But she kept still, and not just because she feared her cries would rouse the serpents. A terrible loyalty to him and to herself silenced her. He could not mean it. He could not do it. He was a Vestrit, she was his family ship. He could not leave her, not for long. He’d get ashore and go up into the dark town. He’d stay there, an hour, a day, a week, men did such things, they went ashore, but they always came back. Of his own free will, he’d come back to her and acknowledge that she was his destiny. She hugged herself tightly and clenched her teeth shut. She would not cry out. She could wait, until he saw for himself and came back on his own. She’d trust that she truly knew his heart.

‘It’s nearly dawn.’

Kennit’s voice was so soft, Etta was scarcely sure she had heard it. ‘Yes,’ she confirmed very quietly. She lay alongside his back, her body not quite touching his. If he was talking in his sleep, she did not wish to wake him. It was seldom that he fell asleep while she was still in the bed, seldom that she was allowed to share his bedding and pillows and the warmth of his lean body for more than an hour or two.

He spoke again, less than a whisper. ‘Do you know this piece? “When I am parted from you, The dawn light touches my face with your hands.”’

‘I don’t know,’ Etta breathed hesitantly. ‘It sounds like a bit of a poem, perhaps… I never had much time for the learning of poetry.’

‘You have no need to learn what you already are,’ he said quietly. He did not try to disguise the fondness in his voice. Etta’s heart near stood still. She dared not breathe. ‘The poem is called, From Kytris To His Mistress. Older than Jamaillia, from the days of the Old Empire.’ Again there was a pause. ‘Ever since I met you, it has made me think of you. Especially the part that says, “Words are not cupped deeply enough to hold my fondness. I bite my tongue and scowl my love, lest passion make me slave.’” A pause. ‘Another man’s words, from another man’s lips. I wish they were my own.’

Etta let the silence follow his words, savoured them as she committed them to memory. In the absence of his breathless whisper, she heard the deep rhythm of his breathing in harmony with the splash and gurgle of the waves against the ship’s bow. It was a music that moved through her with the beating of her blood. She drew a breath and summoned all her courage.

‘Sweet as your words are, I do not need them. I have never needed them.’

‘Then in silence, let us bide. Lie still beside me, until morning turns us out.’

‘I shall,’ she breathed. As gentle as a drifting feather alighting, she laid her hand on his hip. He did not stir, nor turn to her. She did not mind. She did not need him to. Having lived for so long with so little, the words he had spoken to her now would be enough to last her a life. When she closed her eyes, a single tear slid forth from beneath her lashes.

In the dimness of the captain’s cabin, a tiny smile curved his wooden features.

23 JAMAILLIA SLAVERS

THERE WAS A SONG he had learned as a child, about the white streets of Jamaillia shining in the sun. Wintrow found himself humming it as he hurried down a debris-strewn alley. To either side of him, tall wooden buildings blocked the sun and channelled the sea wind. Despite his efforts, the saltwater had reached his priest’s robe. The damp bure slapped and chafed against him as he walked. The winter day was unusually mild, even for Jamaillia. He was not, he told himself, very cold at all. As soon as his skin and robe dried completely, he’d be fine. His feet had become so calloused from his days on shipboard that even the broken crockery and splintered bits of wood that littered the alley did not bother him much. These were things he should remember, he counselled himself. Forget the growling of his empty belly, and be grateful that he was not overly cold.

And that he was free.

He had not realized how his confinement on the ship had oppressed him until he waded ashore. Even before he had dashed the water from his skin and donned his robe, his heart had soared. Free. He was many days from his monastery, and he had no idea how he would make his way there, but he was determined he would. His life was his own again. To know he had accepted the challenge made his heart sing. He might fail, he might be recaptured or fall to some other evil along the way, but he had accepted Sa’s strength and acted. No matter what happened to him after this, he had that to hold to. He was not a coward.

He had finally proved that to himself.

Jamaillia was bigger by far than any city he had ever visited. The size of it daunted him. From the ship, he had focused on the gleaming white towers and domes and spires of the Satrap’s Court in the higher reaches of the city. The steaming of the Warm River was an eternal backdrop of billowing silk to these marvels. But he was in the lower part of the city now. The waterfront was as dingy and miserable as Cress had been, and more extensive. It was dirtier and more wretched than anything he had ever seen in Bingtown. Dockside were the warehouses and ship-outfitters, but above them was a section of town that seemed to consist exclusively of brothels, taverns, druggeries and run-down boarding houses. The only permanent residents were the curled beggars who slept on doorsteps and within scavenged hovels propped up between buildings. The streets were near as filthy as the alleys. Perhaps the gutters and drains had once channelled dirty water away; now they overflowed in stagnant pools, green and brown and treacherous underfoot. It was only too obvious that nightsoil from chamberpots was dumped there as well. A warmer day would probably have produced an even stronger smell and swarms of flies. So there, he reminded himself as he skirted a wider puddle, was yet another thing to be grateful for.

It was early dawn, and this part of the city slept on. Perhaps there was little that folk in this quarter of town deemed worth rising for. Wintrow supposed that night would tell a different story on these streets. But for now, they were deserted and dead, windows shuttered and doors barred. He glanced up at the lightening sky and hastened his steps. It would not be too much longer before his absence from the ship would be noticed. He wanted to be well away from the waterfront before then. He wondered how energetic his father would be in the search for him. Probably very little on his own account; he only valued Wintrow as a way to keep the ship content.

Vivacia.

Even to think the name was like a fist to his heart. How could he have left her? He’d had to, he couldn’t go on like that. But how could he have left her? He felt torn, divided against himself. Even as he savoured his liberty, he tasted loneliness, extreme loneliness. He could not say if it were his, or hers. If there had been some way for him to take the ship and run away, he would have. Foolish as that sounded, he would have. He had to be free. She knew that. She must understand that he had to go.

But he had left her in the trap.

He walked on, torn within. She was not his wife or his child or his beloved. She was not even human. The bond they shared had been imposed upon them both, by circumstance and his father’s will. No more than that. She would understand, and she would forgive him.

In the moment of that thought, he realized that he meant to go back to her. Not today, nor tomorrow, but some day. There would come a time, in some undecided future, perhaps when his father had given up and restored Althea to the ship, when it would be safe for him to return. He would be a priest and she would be content with another Vestrit, Althea or perhaps even Selden or Malta. They would each have a full and separate life, and when they came together of their own independent wills, how sweet their reunion would be. She would admit, then, that his choice had been wise. They would both be wiser by then.

His conscience suddenly niggled at him. Did he hold the intent to return as the only way to assuage his conscience? Did that mean, perhaps, that he suspected what he did today was wrong? How could it be? He was going back to his priesthood, to keep the promises made years ago. How could that be wrong? He shook his head, mystified at himself, and trudged on.

He decided he would not venture into the upper reaches of the city. His father would expect him to go there, to seek sanctuary and aid from Sa’s priests in the Satrap’s Temple. It would be the first place his father would look for him. He longed to go there, for he was certain the priests would not turn him away. They might even be able to aid him to return to his own monastery, though that was a great deal to ask. But he would not ask them, he would not bring his father banging on their doors demanding his return. At one time, the sanctuary of Sa’s temple would have protected even a murderer. But if the outer circles of Jamaillia had degraded to this degree, he somehow doubted that the sanctity of Sa’s temple would be respected as it once was. Better to avoid causing them trouble. There was really no sense to pausing in the city at all. He would begin his long trek across the satrapy of Jamaillia to reach his monastery and home.

He should have felt daunted at the thought of that long journey. Instead he felt elated that, at long last, it was finally begun.

He had never thought that Jamaillia City might have slums, let alone that they would comprise such a large part of the capital city. He passed through one area that a fire had devastated. He estimated that fifteen buildings had burned to the ground, and many others nearby showed scorching and smoke. None of the rubble had been cleared away; the damp ashes gave off a terrible smell. The street became a footpath beaten through debris and ash. It was disheartening, and he reluctantly gave more credence to all the stories he had heard about the current Satrap. If his idle luxury and sybaritic ways were as decadent as Wintrow had heard, that might explain the overflowing drains and rubbish-strewn streets. Money could only be spent once. Perhaps taxes that should have repaired the drains and hired street watchmen had been spent instead on the Satrap’s pleasures. That would account for the sprawling wasteland of tottering buildings, and the general neglect he had seen down in the harbour. The galleys and galleasses of Jamaillia’s patrol fleet were tied there. Seaweed and mussels clung to their hulls, and the bright white paint that had once proclaimed they protected the interests of the Satrap was flaking away from their planks. No wonder pirates now plied the inner waterways freely.

Jamaillia City, the greatest city in the world, the heart and light of all civilization, was rotting at the edges. All his life he had heard legends of this city, of its wondrous architecture and gardens, its grand promenades and temples and baths. Not just the Satrap’s palace, but many of the public buildings had been plumbed for water and drains. He shook his head as he reluctantly waded past yet another overflowing gutter. If the water was standing and clogged here below, how much better could things be in the upper parts of the city? Well, perhaps things were much better along the main thoroughfares, but he’d never know. Not if he wanted to elude his father and whatever searchers he sent after him.

Gradually the circumstances of the city improved. He began to see early vendors offering buns and smoked fish and cheese, the scents of which made his mouth water. Doors began to be opened, people came out to take the shutters down from the windows and once more display their wares. As carts and foot-traffic began to crowd the streets, Wintrow’s heart soared. Surely, in a city of this size, with all these people milling about, his father would never find him.

Vivacia stared across the bright water to the white walls and towers of Jamaillia. In hours, it had not been that long since Wintrow left. Yet it seemed lifetimes had passed since he had clambered down the anchor chain and swum away. The other ships had obscured her view of him. She could not even be absolutely certain he had reached the beach safely. A day ago, she would have insisted that if something had happened to him, she would have felt it. But a day ago, she would have sworn that she knew him better than he did himself, and that he could never simply leave her. What a fool she had been.

‘You must have known when he left! Why didn’t you give an alarm? Where did he go?’

Wood, she told herself. I am only wood. Wood need not hear, wood need not answer.

Wood should not have to feel. She stared up at the city. Somewhere up there, Wintrow walked. Free of his father, free of her. How could he so easily sever that bond? A bitter smile curved her lips. Perhaps it was a Vestrit thing. Had not Althea walked away from her in much the same way?

‘Answer me!’ Kyle demanded of her.

Torg spoke quietly to his captain. ‘I’m so sorry, sir. I should have kept a closer watch on the boy. But who could have predicted this? Why would he run, after all you’ve done for him, all you wanted to give him? Makes no sense to a man like me. Ingratitude like that’s enough to break a father’s heart.’ The words were spoken as if to comfort, but Vivacia knew that every sentence of Torg’s commiseration only deepened Kyle’s fury with Wintrow. And with her.

‘Where did he go and when? Damn you, answer me!’ Kyle raged. He leaned over the railing. He dared to seize a heavy lock of her hair and pull it.

Swift as a snake, she pivoted. Her open hand slapped him away like a man swipes at an annoying cat. He went sprawling on the deck. His eyes went wide in sudden fear and shock. Torg fled, tripping in his fear and then scrabbling away on all fours. ‘Gantry!’ he called out wildly. ‘Gantry, get up here!’ He scurried off to find the first mate.

‘Damn you, Kyle Haven,’ she said in a quiet vicious voice. She did not know where the tone or the words came from. ‘Damn you to the bottom of the briny deep. One by one, you’ve driven them away. You took my captain’s place. You drove his daughter, the companion of my sleeping days, from my decks. And now your own son has fled your tyranny and left me friendless. Damn you.’

He stood slowly. Every muscle in his body was knotted. ‘You’ll be sorry —’ Kyle began in a voice that shook with fear and fury, but she cut him off with a wild laugh.

‘Sorry? How can you make me sorrier than I already am? What deeper misery can you visit upon me than to drive from me those of my own blood? You are false, Kyle Haven. And I owe you nothing, nothing, and nothing is what you shall have from me.’

‘Sir.’ Gantry’s voice came in a low respectful tone. He stood on the main deck, a safe distance from both man and figurehead as he spoke. Torg hovered behind him, both savouring and fearing the conflict. Gantry himself stood straight, but his tanned face had gone sallow. ‘I respectfully suggest you come away from there. You can do no good, and, I fear, much harm. Our best efforts should be made to search for the lad now, before he goes too far and hides too deep. He has no money, nor friends here that we know of. We should be in Jamaillia City right now, putting out word that we are seeking him. And offer a reward. Times are hard for many folk in Jamaillia. Like as not, a few coins will have him back on board before sunset.’

Kyle made a show of considering Gantry’s words. Vivacia knew that he stood where he was, almost within her reach, as a show of boldness. She was aware, too, of Torg watching them, an almost avid look on his face. It disgusted her that he relished this quarrel between them. Abruptly she didn’t care. Kyle wasn’t Wintrow, he wasn’t kin to her. He was nothing.

Kyle nodded to Gantry, but his eyes never left her. ‘Your suggestion has merit. Direct all crew members who have shore time to put out the word that we’ll give a gold piece for the boy returned safe and sound. Half a gold piece in any other condition. A silver for word of where he is, if such words helps us take him ourselves.’ Kyle paused. ‘I’ll be taking Torg and heading down to the slave-markets. The damned boy’s desertion has cost me an early start this day. No doubt the best stock will be taken already. I might have had a whole company of singers and musicians, if I had been down there early on the morning we arrived. Have you any idea what Jamaillian singers and musicians would have been worth in Chalced?’ He spoke as bitterly as if it were Gantry’s failure. He shook his head in disgust. ‘You stay here and see to the modifications in the hold. That needs to be completed as swiftly as possible, for I intend to sail as soon as we have both boy and cargo on board.’

Gantry was nodding to his captain’s words, but several times Vivacia felt his eyes on her. She twisted as much as she could to stare coldly at the three men. Kyle would not look at her, but Gantry’s uneasy glance met her eyes once. He made a tiny motion with his hand, intended for her, she was sure, but she could not decide what it meant. They left the foredeck and both went down into the hold. Some time later she was aware of both Torg and Kyle leaving. And good riddance to them both, she told herself. Again her eyes wandered the white city cloaked in the faint steaming of the Warm River. A city veiled in cloud. Did she hope they would find Wintrow and drag him back to her, or did she hope he would escape his father and be happy? She did not know. She remembered a hope that he would come back to her of his own will. It seemed childish and foolish now.

‘Ship? Vivacia?’ Gantry had not ventured onto the foredeck. Instead he stood on the short ladder and called to her in a quiet voice.

‘You needn’t be afraid to approach me,’ she told him sulkily. Despite being one of Kyle’s men, he was a good sailor. She felt oddly ashamed to have him fear her.

‘I but wanted to ask, is there anything I can do for you? To… ease you?’

He meant to calm her down. ‘No,’ she replied shortly. ‘No, there is nothing. Unless you wish to lead a mutiny.’ She stretched her lips in a semblance of a smile, to show him she was not serious in her request. At least, not quite yet.

‘Can’t do that,’ he replied, quite solemnly. ‘But if there’s anything you need, let me know.’

‘Need. Wood has no needs.’

He went away as softly as he had come, but in a short time, Findow appeared, to sit on the edge of the foredeck and play his fiddle. He played none of the lively tunes he used to set the pace for the crew when they were working the capstan. Instead he played soothingly, tunes with more than a tinge of sadness to them. They were in keeping with her mood, but somehow the simple sound of the fiddle-strings echoing her melancholy lifted her spirits and lessened her pain. Salt tears rolled down her cheeks as she stared at Jamaillia. She had never wept before. She had supposed that tears themselves would be painful, but instead they seemed to ease the terrible tightness inside her.

Deep inside her, she felt the men working. Drills twisted into her timbers, followed by heavy eye-bolts. Lengths of chain were measured across her and then secured to stanchions or heavy staples. Oncoming supplies were mostly water and hard-tack and chains. For the slaves. Slaves. She tried the word on her tongue. Wintrow had believed slavery to be one of the greatest evils that existed in the world, but when he had tried to explain it to her, she could not see much difference between the life of a slave and the life of a sailor. All, it seemed to her, were owned by a master and made to work for as long and hard as that master saw fit. Sailors had very little say about their lives. How could it be much worse to be a slave? She had not been able to grasp it. Perhaps that was why Wintrow had been able to leave her so easily. Because she was stupid. Because she was not, after all, a human being. Tears welled afresh into her eyes, and the slaver Vivacia wept.

Even before they could see the ship itself, Sorcor declared he knew she was a slaver by the tallness of her masts. They were visible through the trees as she came around the island.

‘More sail to run faster, to deliver “fresh” cargo,’ he observed sarcastically. Then he shot Kennit a pleased grin. ‘Or perhaps the slavers are learning they have something to fear. Well, run as they may, they won’t outdistance us. If we put on some sail now, we’ll be on her as soon as she rounds the point.’

Kennit shook his head. ‘The shoals are rocky there.’ He considered a moment. ‘Run up a Trader flag and drag some rope to make us appear heavy-laden. We’ll just be a fat little merchant-vessel ourselves, shall we? Hang off and don’t approach too close until she’s going into Rickert’s Channel. There’s a nice sandy shoal just past there. If we have to run her aground to take her, I don’t want to hole her.’

‘Aye, sir.’ Sorcor cleared his throat. It was not clear whom he next addressed. ‘When we take a slaver, it’s usually pretty bloody. Serpents snapping up bodies is not a fit sight for a woman’s eyes, and slavers always have a snake or two in their wakes. Perhaps the lady should retire to her cabin until this is over.’

Kennit glanced over his shoulder at Etta. It now seemed to him that any time he came on deck, he could find her just behind his left shoulder. It was a bit disconcerting, but he’d decided the best way to deal with it was to ignore it. He found it rather amusing that Sorcor would refer to a whore so deferentially and pretend that she needed some sort of sheltering from the harsher realities of life. Etta, however, looked neither amused nor flattered. Instead there were deep sparks in her dark eyes, and a pinch of colour at the top of each cheek. She wore sturdier stuff this day, a shirt of azure cotton, dark woollen trousers and a short woollen jacket to match. Her black knee-boots were oiled to a shine. He had no idea where those had come from, though she had prattled something about gaming with the crew a few nights ago. A gaudy scarf confined her black hair, leaving only the glossy tips free to brush across her wind-reddened cheeks. Had he not known Etta, he might have mistaken her for a young street tough. She certainly bristled enough at Sorcor to be one.

‘I think the lady can discern what is too bloody or cruel for her taste, and retire at that time,’ Kennit observed dryly.

A small cat smile curved Etta’s lips as she brazenly pointed out, ‘If I enjoy Captain Kennit by night, surely there is little I need to fear by day.’

Sorcor flushed red, scars standing white against his blush. But Etta only shot Kennit a tiny sideways glance to see if he would preen to her flattery. He tried not to, but it was pleasing to see Sorcor discomfited by his woman’s bragging of him. He permitted himself a tiny quirk of his lip acknowledging her. It was enough. She saw it. She flared her nostrils and turned her head, his tigress on a leash.

Sorcor turned away from them both. ‘Well, boys, let’s run the masquerade,’ he shouted to the crew and they tumbled to his command. Kennit’s Raven came down and the Trader flag, taken long ago with a merchant-ship, was run up and the rope drags put over the side. All but a fraction of their crew went below. Now the Marietta moved sedately as a laden cargo-ship, and the sailors who manned her deck carried no weapons. Even as the slaver rounded the point and became completely visible to them, Kennit could tell they would overtake her easily.

He observed her idly. As Sorcor had observed, her three masts were taller than usual, to permit her more sail. A canvas tent for the crew’s temporary shelter billowed on the deck; no doubt the sailors working the ship could no longer abide the stench of their densely-packed cargo, and so had forsaken the forecastle for airier quarters. The Sicerna, as the name across her stern proclaimed her, had been a slaver for some years. The gilt had flaked from her carvings, and stains down her sides told of human waste sloshed carelessly overboard.