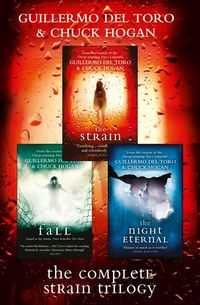

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Then she noticed that one of the shades was up now. The fine hairs went so prickly on the back of her neck, she put her hand there to console them, like soothing a jumpy pet. She had missed seeing that shade before. It had always been up—always.

Maybe …

Inside the plane, the darkness stirred. And Lo felt as if something were observing her from within it.

She whimpered, just like a child, but couldn’t help it. She was paralyzed. A throbbing rush of blood, rising as though commanded, tightened her throat …

And she understood it then, unequivocally: something in there was going to eat her …

The gusting wind started up again, as though it had never paused, and Lo didn’t need any more prompting. She backed down the ramp and jumped inside her conveyor, putting it in reverse with the alert beeping and her ramp still up. The crunching noise was one of the blue taxiway lights beneath her treads as she sped away, half on and half off the grass, toward the approaching lights of half a dozen emergency vehicles.

JFK International Control Tower

CALVIN BUSS had switched to a different headset, and was giving orders as set forth in the FAA national playbook for taxiway incursions. All arrivals and departures were halted in a five-mile airspace around JFK. This meant that volume was stacking up fast. Calvin canceled breaks and ordered every on-shift controller to try to raise Flight 753 on every available frequency. It was as close to chaos in the JFK tower as Jimmy the Bishop had ever seen.

Port Authority officials—guys in suits muttering into Nextels—gathered at his back. Never a good sign. Funny how people naturally assemble when faced with the unexplained.

Jimmy the Bishop tried his call again, to no avail.

One suit asked him, “Hijack signal?”

“No,” said Jimmy the Bishop. “Nothing.”

“No fire alarm?”

“Of course not.”

“No cockpit door alarm?” said another.

Jimmy the Bishop saw that they had entered the “stupid questions” phase of the investigation. He summoned the patience and good judgment that made him a successful air-traffic controller. “She came in smooth and set down soft. Regis 7-5-3 confirmed the gate assignment and turned off the runway. I terminated radar and transitioned it over to ASDE.”

Calvin said, one hand over his earphone mic, “Maybe the pilot had to shut down?”

“Maybe,” said Jimmy the Bishop. “Or maybe it shut down on him.”

A suit said, “Then why haven’t they opened a door?”

Jimmy the Bishop’s mind was already spinning on that. Passengers, as a rule, won’t sit still for a minute longer than they had to. The previous week, a jetBlue arriving from Florida had very nearly undergone a mutiny, and that was over stale bagels. Here, these people had been sitting tight for, what—maybe fifteen minutes. Completely in the dark.

Jimmy the Bishop said, “It’s got to be starting to get hot in there. If the electrical is shut down, there’s no air circulating inside. No ventilation.”

“So what the hell are they waiting for?” said another suit.

Jimmy the Bishop felt everyone’s anxiety going up. That hole in your gut when you realize that something is about to happen, something really, really wrong.

“What if they can’t move?” he muttered before he could stop himself from speaking.

“A hostage situation? Is that what you mean?” asked the suit.

The Bishop nodded quietly … but he wasn’t thinking that. For whatever reason, all he could think was … souls.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE PORT AUTHORITY’S aircraft rescue firefighters went out on a standard airliner distress deployment, six vehicles including the fuel spill foamer, pumper, and aerial ladder truck. They pulled up at the stuck baggage conveyor before the blue lamps edging Foxtrot. Captain Sean Navarro hopped off the back step of the ladder truck, standing there in his helmet and fire suit before the dead plane. The rescue vehicles’ lights flashing against the fuselage imbued the aircraft with a fake red pulse. It looked like an empty plane set out for a nighttime training drill.

Captain Navarro went up to the front of the truck and climbed in with the driver, Benny Chufer. “Call in to maintenance and get those staging lights out here. Then pull up behind the wing.”

Benny said, “Our orders are to hang back.”

Captain Navarro said, “That’s a plane full of people there. We’re not paid to be glorified road flares. We’re paid to save lives.”

Benny shrugged and did as the cap told him. Captain Navarro climbed back out of the rig and up onto the roof, and Benny raised the boom just enough to get him up on the wing. Captain Navarro switched on his flashlight and stepped over the trailing edge between the two raised flaps, his boot landing right where it said, in bold black lettering, DON’T STEP HERE.

He walked along the broadening wing, twenty feet above the tarmac. He went to the over-wing exit, the only door on the aircraft installed with an exterior emergency release. There was a small, unshaded window set in the door, and he tried to peer through, past the beads of condensation inside the double-thick glass, seeing nothing inside except more darkness. It had to be as stifling as an iron lung in there.

Why weren’t they calling out for help? Why wasn’t he hearing any movement inside? If still pressurized, then the plane was airtight. Those passengers were running out of oxygen.

With his fire gloves on, he pushed in the twin red flaps and pulled the door handle out from its recess. He rotated it in the direction of the arrows, nearly 180 degrees, and tugged. The door should have popped outward then, but it would not open. He pulled again, but knew immediately that his effort was useless—no give whatsoever. There was no way it could have been stuck from the inside. The handle must have jammed. Or else something was holding it from the inside.

He went back down wing to the ladder top. He saw an orange utility light spinning, an airport cart on its way out from the international terminal. Closer, he saw it was driven by blue-jacketed agents of the Transportation Security Administration.

“Here we go,” muttered Captain Navarro, starting down the ladder.

There were five of them, each one introducing himself in turn, but Captain Navarro didn’t waste any effort trying to remember names. He had come to the plane with fire engines and foaming equipment; they came with laptops and mobile handhelds. For a while he just stood and listened while they talked into their devices and over each other:

“We need to think long and hard before we push the Homeland Security button here. Nobody wants a shit storm for nothing.”

“We don’t even know what we have. You ring that bell and scramble fighters up here from Otis Air Force Base, you’re talking about panicking the entire eastern seaboard.”

“If it is a bomb, they waited until the last possible moment.”

“Explode it on U.S. soil, maybe.”

“Maybe they’re playing dead for a while. Staying radio dark. Luring us closer. Waiting for the media.”

One guy was reading from his phone. “I have the flight originating from Tegel, in Berlin.”

Another spoke into his. “I want someone on the ground in Germany who sprechen ze English. We need to know if they’ve seen any suspicious activity there, any breaches. Also, we need a primer on their baggage-handling procedures.”

Another ordered: “Check the flight plan and reclear the passenger manifest. Yes—every name, run them again. This time accounting for spelling variations.”

“Okay,” said another, reading from his handheld. “Full specs. Plane reg is N323RG. Boeing 777–200LR. Most recent transit check was four days ago, at Atlanta Hartsfield. Replaced a worn duct slider on the left engine’s thrust reverser, and a worn mount bushing on the right. Deferred repair of a dent in the left-aft inboard flap assembly due to flight schedule. Bottom line—she got a clean bill of health.”

“Triple sevens are new orders, aren’t they? A year or two out?”

“Three hundred and one max capacity. This flight boarded two ten. A hundred and ninety-nine passengers, two pilots, nine cabin crew.”

“Any unticketed?” That meant infants.

“I’m showing no.”

“Classic tactic,” said the one focused on terror. “Create a disturbance, draw first responders, gain an audience—then detonate for max impact.”

“If so, then we’re already dead.”

They looked at each other uncomfortably.

“We need to pull these rescue vehicles back. Who was that fool up there stomping on the wing?”

Captain Navarro edged forward, surprising them with a response. “That was me.”

“Ah. Well.” The guy coughed once into his fist. “That’s maintenance personnel only up there, Captain. FAA regs.”

“I know it.”

“Well? What’d you see? Anything?”

Navarro said, “Nothing. Saw nothing, heard nothing. All the window shades are drawn down.”

“Drawn down, you say? All of them?”

“All of them.”

“Did you try the over-wing exit?”

“I did indeed.”

“And?”

“It was stuck.”

“Stuck? That’s impossible.”

“It’s stuck,” said Captain Navarro, showing more patience with these five than he did with his own kids.

The senior man stepped away to make a call. Captain Navarro looked at the others. “So what are we going to do here, then?”

“That’s what we’re waiting to find out.”

“Waiting to find out? You have how many passengers on this plane? How many 911 calls have they made?”

One man shook his head. “No mobile 911 calls from the plane yet.”

“Yet?” said Captain Navarro.

The guy next to him said, “Zero for one-ninety-nine. Not good.”

“Not good at all.”

Captain Navarro looked at them in amazement. “We have to do something, and now. I don’t need permission to grab a fire ax and start smashing in windows when people are dead or dying in there. There is no air inside that plane.”

The senior man came back from his phone call. “They’re bringing out the torch now. We’re cutting her open.”

Dark Harbor, Virginia

CHESAPEAKE BAY, black and churning at that late hour.

Inside the glassed-in patio of the main house, on a scenic bluff overlooking the bay, a man reclined in a specially made medical chair. The lights were dimmed for his comfort as well as for modesty. The industrial thermostats, of which there were three for this room alone, maintained a temperature of sixty-two degrees Fahrenheit. Stravinsky played quietly, The Rite of Spring, piped in through discreet speakers to obscure the relentless shushing pump of the dialysis machine.

A faint plume of breath emerged from his mouth. An onlooker might have believed the man near death. Might have thought they were witnessing the last days or weeks of what was, judging by the sprawling seventeen-acre estate, a dramatically successful life. Might even have remarked on the irony of a man of such obvious wealth and position meeting the same end as a pauper.

Only, Eldritch Palmer was not at the end. He was in his seventy-sixth year, and he had no intention of giving up on anything. Nothing at all.

The esteemed investor, businessman, theologian, and high-powered confidant had been undergoing the same procedure for three to four hours every evening for the past seven years of his life. His health was frail and yet manageable, overseen by round-the-clock physicians and aided by hospital-grade medical equipment purchased for his private, in-home use.

Wealthy people can afford excellent health care, and they can also afford to be eccentric. Eldritch Palmer kept his peculiarities hidden from public view, even from his inner circle. The man had never married. He had never sired an heir. And so a major topic of speculation about Palmer was what plans he might have for his vast fortune after his death. He had no second-in-command at his primary investment entity, the Stoneheart Group. He had no public affiliation with any foundations or charities, unlike the two men jockeying for number one with him on the annual Forbes list of the world’s richest Americans, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and Berkshire Hathaway investor Warren Buffett. (If certain gold reserves in South America and other holdings by shadow corporations in Africa were factored into Forbes’s accounting, Palmer alone would hold the top spot on the list.) Palmer had never even drafted a will, an estate-planning lapse unthinkable for a man with even one one-thousandth of his wealth and treasure.

But Eldritch Palmer was, quite simply, not planning to die.

Hemodialysis is a procedure in which blood is removed from the body through a system of tubing, ultrafiltered through a dialyzer, or artificial kidney, and then returned to the body cleansed of waste products and impurities. Ingoing and outgoing needles are inserted into a synthetic arteriovenous graft semipermanently installed in the forearm. The machine for this procedure was a state-of-the-art Fresenius model, continuously monitoring Palmer’s critical parameters and alerting Mr. Fitzwilliam, never more than two rooms away, of any readings outside the normal range.

Loyal investors were accustomed to Palmer’s perpetually gaunt appearance. It had essentially become his trademark, an ironic symbol of his monetary strength, that such a delicate, ashen-looking man should wield such power and influence in both international finance and politics. His legion of faithful investors numbered thirty thousand strong, a financially elite bloc of people: the buy-in was two million dollars, and many who had invested with Palmer for decades were worth mid-nine figures. The buying power of his Stoneheart Group gave him enormous economic leverage, which he put to effective and occasionally ruthless use.

The west doors opened from the wide hallway, and Mr. Fitzwilliam, who doubled as the head of Palmer’s personal security detail, entered with a portable, secure telephone on a sterling-silver serving tray. Mr. Fitzwilliam was a former U.S. Marine with forty-two confirmed combat kills and a quick mind, whose postmilitary medical schooling Palmer had financed. “The undersecretary for Homeland Security, sir,” he said, with a plume of breath steaming in the cold room.

Normally Palmer allowed no intrusions during his nightly replenishment, preferring instead to use the time contemplatively. But this was a call he had been expecting. He accepted the telephone from Mr. Fitzwilliam, and waited for him to dutifully withdraw.

Palmer answered, and was informed about the dormant airplane. He learned that there was considerable uncertainty as to how to proceed by officials at JFK. The caller spoke anxiously, with self-conscious formality, like a proud child reporting a good deed. “This is a highly unusual event, and I thought you’d want to be apprised immediately, sir.”

“Yes,” Palmer told the man. “I do appreciate such courtesy.”

“Ha-have a good night, sir.”

Palmer hung up and set the phone down in his small lap. A good night indeed. He felt a pang of anticipation. He had been expecting this. And now that the plane had landed, he knew it had begun—and in what spectacular fashion.

Excitedly, he turned to the large-screen television on the side wall and used the remote control on the arm of his chair to activate the sound. Nothing about the airplane yet. But soon …

He pressed the button on an intercom. Mr. Fitzwilliam’s voice said, “Yes, sir?”

“Have them ready the helicopter, Mr. Fitzwilliam. I have some business to attend to in Manhattan.”

Eldritch Palmer rang off, then looked through the wall of windows out over the great Chesapeake Bay, roiling and black, just south of where the steely Potomac emptied into her dark depths.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE MAINTENANCE CREW wheeled oxygen tanks underneath the fuselage. Cutting in was an emergency procedure of last resort. All commercial aircraft were constructed with specified “chop-out” areas. The triple seven’s chop out was in the rear fuselage, beneath the tail, between the aft cargo doors on the right side. The LR in Boeing 777–200LR stood for long range, and as a C-market model with a top range exceeding 9,000 nautical miles (nearly 11,000 U.S.) and a fuel capacity of up to 200,000 liters (more than 50,000 gallons), the aircraft had, in addition to the traditional fuel tanks inside the wing bodies, three auxiliary tanks in the rear cargo hold—thus the need for a safe chop-out area.

The maintenance crew was using an Arcair slice pack, an exothermic torch favored for disaster work not only because it was highly portable, but because it was also oxygen powered, using no hazardous secondary gases such as acetylene. The work of cutting through the thick fuselage shell would take about one hour.

No one on the tarmac at this point was anticipating a happy outcome. There had been no 911 calls from passengers inside the aircraft. No light, noise, or signal of any kind emanating from inside Regis 753. The situation was mystifying.

A Port Authority emergency services unit mobile-command vehicle was cleared through to the terminal apron, set up behind powerful construction lights trained on the jet. Their SWAT team was trained for evacuations, hostage rescue, and antiterrorism assaults on the bridges, tunnels, bus terminals, airports, PATH rail lines, and seaports of New York and New Jersey. Tactical officers were outfitted with light body armor and Heckler-Koch submachine guns. A pair of German shepherds were out sniffing around the main landing gear—two sets of six enormous tires—trotting around with their noses in the air as if they could smell the trouble here too.

Captain Navarro wondered for a moment if anyone was actually still on board. Hadn’t there been a Twilight Zone where a plane landed empty?

The maintenance crew sparked up the torches and was just starting in on the underside of the hull when one of the canines started howling. The dog was baying, actually, and spinning around and around on his leash in tight circles.

Captain Navarro saw his ladder man, Benny Chufer, pointing up at the midsection of the aircraft. A thin, black shadow appeared before his eyes. A vertical slash of darkest black, disrupting the perfectly smooth breast of the fuselage.

The exit door over the wing. The one Captain Navarro hadn’t been able to budge.

It was open now.

It made no sense to him, but Navarro kept quiet, struck dumb by the sight. Maybe a latch failure, a malfunction in the handle … maybe he had not tried hard enough … or maybe—just maybe—someone had finally opened the door.

JFK International Control Tower

THE PORT AUTHORITY had pulled Jimmy the Bishop’s audio. He was standing, as always, waiting to review it with the suits, when their phones started ringing like crazy.

“It’s open,” one guy reported. “Somebody opened up 3L.”

Everybody was standing now, trying to see. Jimmy the Bishop looked out from the tower cab at the lit-up plane. The door did not look open from up here.

Calvin Buss said, “From the inside? Who’s coming out?”

The guy shook his head, still on his phone. “No one. Not yet.”

Jimmy the Bishop grabbed a small pair of birders off the ledge and checked out Regis 753 for himself.

There it was. A sliver of black over the wing. A seam of shadow, like a tear in the hull of the aircraft.

Jimmy’s mouth went dry at the sight. Those doors pull out slightly when first unlocked, then swivel back and fold against the interior wall. So, technically, all that had happened was that the airlock had been disengaged. The door wasn’t quite open yet.

He set the field glasses back on the ledge and backed away. For some reason, his mind was telling him that this would be a good time to run.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE GAS AND RADIATION SENSORS lifted to the door crack both read clear. An emergency service unit officer lying on the wing managed to pull out the door a few extra inches with a long, hooked pole, two other armed tactical officers covering him from the tarmac below. A parabolic microphone was inserted, returning all manner of chirps, beeps, and ring tones: the passengers’ mobile phones going unanswered. Eerie and plaintive sounding, like tiny little personal distress alarms.

They then inserted a mirror attached at the end of a pole, a large-size version of the sort of dental instrument used to examine back teeth. All they could see were the two jump seats inside the between-classes area, both unoccupied.

Bullhorn commands got them nowhere. No response from inside the aircraft: no lights, no movement, no nothing.

Two ESU officers in light body armor stood back from the taxiway lights for a briefing. They viewed a cross-section schematic, showing passengers seated ten abreast inside the coach cabin they would be entering: three each on the row sides and four across the middle. Airplane interior was tight, and they traded their H-K submachine guns for more manageable Glock 17s, preparing for close combat.

They strapped on radio-enabled gas masks fitted with flip-down night-vision specs, and snapped mace, zip cuffs, and extra magazine pouches to their belts. Q-tip – size cameras, also with passive infrared lenses, were mounted onto the tops of their ESU helmets.

They went up the fire rescue ladder onto the wing, and advanced to the door. They pulled up flat against the fuselage on either side of it, one man folding the door back against the interior wall with his boot, then curling inside, low and straight ahead to a near partition, staying down on his haunches. His partner followed him aboard.

The bullhorn spoke for them:

“Occupants of Regis 753. This is the New York – New Jersey Port Authority. We are entering the aircraft. For your own safety, please remain seated and lace your fingers on top of your heads.”

The lead man waited with his back to the partition, listening. His mask dulled sound into a jarlike roar, but he could discern no movement inside. He flipped down his NVD and the interior of the plane went pea-soup green. He nodded to his partner, readied his Glock, and on a three count swept into the wide cabin.

Worth Street, Chinatown

Ephraim Goodweather couldn’t tell if the siren he heard was blaring out in the street—which is to say, real—or part of the sound track of the video game he was playing with his son, Zack.

“Why do you keep killing me?” asked Eph.

The sandy-haired boy shrugged, as though offended by the question. “That’s the whole point, Dad.”

The television stood next to the broad west-facing window, far and away the best feature of this tiny, second-story walk-up on the southern edge of Chinatown. The coffee table before them was cluttered with open cartons of Chinese food, a bag of comics from Forbidden Planet, Eph’s mobile phone, Zack’s mobile phone, and Zack’s smelly feet. The game system was new, another toy purchased with Zack in mind. Just as his grandmother used to juice the inside of an orange half, so did Eph try to squeeze every last bit of fun and goodness out of their limited time together. His only son was his life, was his air and water and food, and he had to load up on him when he could, because sometimes a week could pass with only a phone call or two, and it was like going a week without seeing the sun.

“What the …” Eph thumbed his controller, this foreign feeling wireless gadget in his hand, still hitting all the wrong buttons. His soldier was punching the ground. “At least let me get up.”