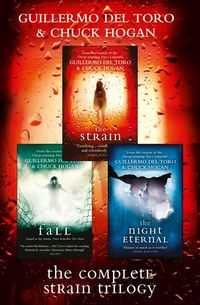

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Boeing representatives en route from Washington State had already disclaimed the 777’s complete shutdown as “mechanically impossible.” A Regis Air vice president, roused from his bed in Scarsdale, was insisting that a team of Regis’s own mechanics be the first to board the aircraft for inspection, once the medical quarantine was lifted. (Corruption of the air-circulation system was the current prevailing cause-of-death theory.) The German ambassador to the United States and his staff were still awaiting their diplomat’s pouch, Eph leaving them cooling their heels in Lufthansa’s Senator Lounge inside terminal 1. The mayor’s press secretary made plans for an afternoon news conference, and the police commissioner arrived with the head of his counter-terrorism bureau inside the rolling headquarters of the NYPD’s critical response vehicle.

By midmorning, all but eighty corpses had been unloaded. The identification process was proceeding speedily, thanks to passport scans and the detailed passenger manifest.

During a suit break, Eph and Nora conferred with Jim outside the containment zone, the bulk of the aircraft fuselage visible over the curtain screens. Airplanes were taking off and landing again outside; they could hear the thrusters gaining and decelerating overhead, and feel the stir in the atmosphere, the agitation of air.

Eph asked Jim, between gulps of bottled water, “How many bodies can the M.E. in Manhattan handle?”

Jim said, “Queens has jurisdiction here, but you’re right, the Manhattan headquarters is the best equipped. Logistically, we’re going to be spreading the victims out among those two and Brooklyn and the Bronx. So, about fifty each.”

“How are we going to transport them?”

“Refrigerated trucks. Medical examiner said that’s how they did the World Trade Center remains. Fulton Fish Market in Lower Manhattan, they’ve been contacted.”

Eph often thought of disease control as a wartime resistance effort, he and his team fighting the good fight while the rest of the world tried to get on with their daily lives under the cloud of occupation, the viruses and bacteria that plagued them. In this scenario, Jim was the underground radio broadcaster, conversant in three languages, who could procure anything from butter to arms to safe passage out of Marseilles.

Eph said, “Nothing from Germany?”

“Not yet. They shut down the airport for two hours, a full security check. No employees sick at the airport, no sudden illnesses being reported to hospitals.”

Nora was anxious to speak. “Nothing here adds up.”

Eph nodded in agreement. “Go ahead.”

“We have a plane full of corpses. Were this caused by a gas, or some aerosol in the ventilation system—accidental or not—they would not have all gone so … I have to say, so peacefully. There would have been choking, flailing. Vomiting. Turning blue. People with different body types going down at different times. And attendant panic. Now—if instead this was an infectious event, then we have some kind of crazy-sudden, totally new emerging pathogen, something none of us have ever seen. Indicating something man-made, created in a lab. And at the same time, remember, it’s not just the passengers who died—the plane itself died too. Almost as though some thing, some incapacitating thing, hit the airplane itself, and wiped out everything inside it, including the passengers. But that’s not exactly accurate, is it? Because, and I think this is the most important question of all right now, who opened the door?” She looked back and forth between Eph and Jim. “I mean—it could have been the pressure change. Maybe the door had already been unlocked, and the aircraft’s decompression forced it open. We can come up with cute explanations for just about anything, because we’re medical scientists, that’s what we do.”

“And those window shades,” said Jim. “People always look out the windows during landing. Who closed them all?”

Eph nodded. He had been so focused on the details all morning, it was good to step back and see strange events from a distance. “This is why the four survivors are going to be key. If they witnessed anything.”

Nora said, “Or were otherwise involved.”

Jim said, “All four are in critical but stable condition in the isolation wing at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center. Captain Redfern, the third pilot, male, thirty-two. A lawyer from Westchester County, female, forty-one. A computer programmer from Brooklyn, male, forty-four. And a musician, a celebrity from Manhattan and Miami Beach, male, thirty-six. His name is Dwight Moorshein.”

Eph shrugged. “Never heard of him.”

“He performs under the name Gabriel Bolivar.”

Eph said, “Oh.”

Nora said, “Ew.”

Jim said, “He was traveling incognito in first class. No fright makeup, no crazy contact lenses. So there will be even more media heat.”

Eph said, “Any connection between the survivors?”

“None we see yet. Maybe their med workup will find something. They were scattered throughout the plane, the programmer was flying coach, the lawyer in business, the singer first class. And Captain Redfern, of course, up in the flight deck.”

“Baffling,” said Eph. “But it’s something anyway. If they regain consciousness, that is. Long enough for us to get some answers out of them.”

One of the Port Authority officers came around for Eph. “Dr. Goodweather, you better get back in there,” he said. “The cargo hold. They found something.”

Through the side cargo hatch, inside the underbelly of the 777, they had already begun off-loading the rolling steel luggage cabinets, to be opened and inspected by the Port Authority HAZMAT team. Eph and Nora sidestepped the remaining train-linked containers, wheels locked into floor tracks.

At the far end of the hold lay a long, rectangular box, black, wooden, and heavy looking, like a grand cabinet laid out on its back. Unvarnished ebony, eight or so feet long by four feet wide by three high. Taller than a refrigerator. The top side was edged all around with intricate carving, labyrinthine flourishes accompanied by lettering in an ancient or perhaps made-to-look-ancient language. Many of the swirls resembled figures, flowing human figures—and perhaps, with a little imagination, faces screaming.

“No one’s opened it yet?” asked Eph.

The HAZMAT officers all shook their heads. “We haven’t touched the thing,” one said.

Eph checked the back of it. Three orange restraining straps, their steel hooks still in the floor eyelets, lay on the floor next to the cabinet. “These straps?”

“Undone when we came in,” said another.

Eph looked around the hold. “That’s impossible,” he said. “If this thing was left unrestrained during transit, it would have done major damage to the luggage containers, if not the interior walls of the cargo hold itself.” He looked it over again. “Where’s its tag? What does the cargo manifest say?”

One of the officers had a sheaf of laminated pages in his gloved hand, bound by a single ring clasp. “It’s not here.”

Eph went over to see for himself. “That can’t be.”

“The only irregular cargo listed here, other than three sets of golf clubs, is a kayak.” The guy pointed to the side wall where, bound by the same type of orange ratchet straps, a plastic-wrapped kayak lay plastered with airline luggage stickers.

“Call Berlin,” said Eph. “They must have a record. Somebody there remembers this thing. It must weigh four hundred pounds, easy.”

“We did that already. No record. They’re going to call in the baggage crew and question them one by one.”

Eph turned back to the black cabinet. He ignored the grotesque carvings, bending to examine the sides, locating three hinges along either top edge. The lid was a door, split down the middle the long way, two half doors that opened out. Eph touched the carved lid with his gloved hand, then he reached under the lid, trying to open the heavy doors. “Anybody want to give me a hand?”

One officer stepped forward, wrapping his gloved fingers underneath the lip of the lid opposite Eph. Eph counted to three, and they opened both heavy doors at once.

The doors stood open on sturdy, broad-winged hinges. The odor that wafted out of the box was corpselike, as though the cabinet had been sealed for a hundred years. It looked empty, until one of the officers switched on a flashlight and played the beam inside.

Eph reached in, his fingers sinking into a rich, black loam. The soil was as welcoming and soft as cake mix and filled up the bottom two-thirds of the box.

Nora took a step back from the open cabinet. “It looks like a coffin,” said Nora.

Eph withdrew his fingers, shaking off the excess, and turned to her, waiting for a smile that never came. “A little big for that, isn’t it?”

“Why would someone ship a box of dirt?” she asked.

“They wouldn’t,” Eph said. “There had to be something inside.”

“But how?” said Nora. “This plane is under total quarantine.”

Eph shrugged. “How do we explain anything here? All I know for sure is, we have an unlocked, unstrapped container here without a bill of lading.” He turned to the others. “We need to sample the soil. Dirt retains trace evidence well. Radiation, for example.”

One of the officers said, “You think whatever agent was used to overcome the passengers …?”

“Was shipped over in here? That’s the best theory I’ve heard all day.”

Jim’s voice called from below them, outside the plane. “Eph? Nora?”

Eph called back, “What is it, Jim?”

“I just got a call from the isolation ward at Jamaica Hospital. You’re going to want to get over there right away.”

Jamaica Hospital Medical Center

THE HOSPITAL FACILITY was just ten minutes north of JFK, along the Van Wyck Expressway. Jamaica was one of the four designated Centers for Bioterrorism Preparedness Planning in New York City. It was a full participant in the Syndromic Surveillance System, and Eph had run a Canary workshop there just a few months before. So he knew his way to the airborne infection isolation ward on the fifth floor.

The metal double doors featured a prominent blaze-orange, tri-petaled biohazard symbol, indicating a real or potential threat to cellular materials or living organisms. Printed warnings read:

ISOLATION AREA:

CONTACT PRECAUTION MANDATORY, AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY.

Eph displayed his CDC credentials at the desk, and the administrator recognized him from previous biocontainment drills. She walked him inside. “What is it?” he asked.

“I really don’t mean to be melodramatic,” she said, waving her hospital ID over the reader, opening the doors to the ward, “but you need to see it for yourself.”

The interior walkway was narrow, this being the outer ring of the isolation ward, occupied mainly by the nurses’ station. Eph followed the administrator behind blue curtains into a wide vestibule containing trays of contact supplies—gowns, goggles, gloves, booties, and respirators—and a large, rolling garbage barrel lined with a red biohazard trash bag. The respirator was an N95 half mask, efficiency rated to filter out 95 percent of particles 0.3 microns in size or larger. That meant it offered protection from most airborne viral and bacteriological pathogens, but not against chemical or gas contaminants.

After his full contact suiting at the airport, Eph felt positively exposed in a hospital mask, surgical cap, barrier goggles, gown, and shoe covers. The similarly attired administrator then pressed a plunger button, opening an interior set of doors, and Eph felt the vacuumlike pull upon entering, the result of the negative-pressure system, air flowing into the isolation area so that no particles could blow out.

Inside, a hallway ran left to right off the central supply station. The station consisted of a crash cart packed with drugs and ER supplies, a plastic-sheathed laptop and intercom system for communicating with the outside, and extra barrier supplies.

The patient area was a suite of eight small rooms. Eight total isolation rooms for a borough with a population of more than two and a quarter million. “Surge capacity” is the disaster preparedness term for a health care system’s ability to rapidly expand beyond normal operating services, to satisfy public health demands in the event of a large-scale public health emergency. The number of hospital beds in New York State was about 60,000 and falling. The population of New York City alone was 8.1 million and rising. Canary was funded in the hopes of mending this statistical shortfall, as a sort of disaster preparedness stopgap. The CDC termed that political expedience “optimistic.” Eph preferred the term “magical thinking.”

He followed the administrator into the first room. This was not a full biological isolation tank; there were no air locks or steel doors. This was routine hospital care in a segregated setting. The room was tile floored and fluorescently lit. The first thing Eph saw was the discarded Kurt pod against the side wall. A Kurt pod is a disposable, plastic-boxed stretcher, like a transparent box coffin, with a pair of round glove ports on each long side, and fitted with removable exterior oxygen tanks. A jacket, shirt, and pants were piled next to it, cut away from the patient with surgical scissors, the Regis Air winged-crown logo visible on the overturned pilot’s hat.

The hospital bed in the center of the room was tented with transparent plastic curtains, outside which stood monitoring equipment and an electronic IV drip tree laden with bags. The railed bed bore green sheets and large white pillows, and was set in the upright position.

Captain Doyle Redfern sat in the middle of the bed, his hands in his lap. He was bare-legged, clad only in a hospital johnny, and appeared alert. But for the IV pick in his hand and arm, and the drawn expression on his face—he looked as though he had dropped ten pounds since Eph had found him inside the cockpit—he looked for all the world like a patient awaiting a checkup.

He looked up hopefully as Eph approached. “Are you from the airline?” he asked.

Eph shook his head, dumbfounded. Last night, this man had gasped and tumbled to the floor inside the cockpit of Flight 753, eyes rolling back into his skull, seemingly near death.

The thin mattress creaked as the pilot shifted his weight. He winced as though from stiffness, and then asked, “What happened on the plane?”

Eph couldn’t hide his disappointment. “That’s what I came here hoping to ask you.”

Eph stood facing the rock star Gabriel Bolivar, who sat perched on the edge of the bed like a black-haired gargoyle draped in a hospital johnny. Without the fright makeup, he was surprisingly handsome, in a stringy-haired, hard-living way.

“The mother of all hangovers,” Bolivar said.

“Any other discomfort?” asked Eph.

“Plenty. Man.” He ran his hand through his long, black hair. “Never fly commercial. That’s the moral of this story.”

“Mr. Bolivar, can you tell me, what is the last thing you remember about the landing?”

“What landing? I’m serious. I was hitting the vodka tonics pretty hard most of the flight—I’m sure I slept right through it.” He looked up, squinting into the light. “How about some Demerol, huh? Maybe when the refreshment cart swings by?”

Eph saw the scars crisscrossing Bolivar’s bare arms, and remembered that one of his signature concert moves was cutting himself onstage. “We’re trying to match passengers with their possessions.”

“That’s easy. I had nothing. No luggage, just my phone. Charter plane broke down, I boarded this flight with about one minute to spare. Didn’t my manager tell you?”

“I haven’t spoken to him yet. I’m asking specifically about a large cabinet.”

Bolivar stared at him. “This some kind of mental test?”

“In the cargo area. An old box, partially filled with soil.”

“No idea what you’re talking about.”

“You weren’t transporting it back from Germany? It seems like the kind of thing someone like you might collect.”

Bolivar frowned. “It’s an act, dude. A fucking show, a spectacle. Goth greasepaint and hard-core lyrics. Google me up—my father was a Methodist preacher and the only thing I collect is pussy. Speaking of which, when the hell am I getting out of here?”

Eph said, “We have a few more tests to run. We want to give you a clean bill of health before we let you go.”

“When do I get my phone back?”

“Soon,” said Eph, making his way out.

The administrator was having trouble with three men outside the entrance to the isolation ward. Two of the men towered over Eph, and had to be Bolivar’s bodyguards. The third was smaller and carried a briefcase, and smelled distinctly of lawyer.

Eph said, “Gentlemen, this is a restricted area.”

The lawyer said, “I’m here to discharge my client Gabriel Bolivar.”

“Mr. Bolivar is undergoing tests and will be released at the earliest possible convenience.”

“And when will that be?”

Eph shrugged. “Two, maybe three days, if all goes well.”

“Mr. Bolivar has petitioned for his release into the care of his personal physician. I have not only power of attorney, but I can function as his health care proxy if he is in any way disabled.”

“No one gets in to see him but me,” said Eph. To the administrator, he said, “Let’s post a guard here immediately.”

The attorney stepped up. “Listen, Doctor. I don’t know much about quarantine law, but I’m pretty sure it takes an executive order from the president to hold someone in medical isolation. May I, in fact, see said order?”

Eph smiled. “Mr. Bolivar is now a patient of mine, as well as the survivor of a mass casualty. If you leave your number at the nurses’ desk, I will do my best to keep you abreast of his recovery—with Mr. Bolivar’s consent, of course.”

“Look, Doc.” The attorney put his hand on Eph’s shoulder in a manner Eph did not like. “I can get quicker results than a court injunction simply by mobilizing my client’s rabid fan base.” He included the administrator in this threat. “You want a mob of Goth chicks and assorted freaks protesting outside this hospital, running wild through these halls, trying to get in to see him?”

Eph looked at the attorney’s hand until the attorney removed it from his shoulder. He had two more survivors to see. “Look, I really don’t have time for this. So let me just ask you some questions straight out. Does your client have any sexually transmitted diseases I should know about? Does he have any history of narcotics use? I’m only asking because, if I have to go look up his entire medical record, well, those things have a way of getting into the wrong hands. You wouldn’t want his full medical history leaked out to the press—right?”

The attorney stared at him. “That is privileged information. Releasing it would be a felony violation.”

“And a real potential embarrassment,” said Eph, holding the attorney’s eye another second for maximum impact. “I mean, imagine if somebody put your complete medical history out there on the Internet for everyone to see.”

The attorney was speechless as Eph started away past the two bodyguards.

Joan Luss, law-firm partner, mother of two, Swarthmore grad, Bronxville resident, Junior League member, was sitting on a foam mattress in her isolation-ward hospital bed, still tied up in that ridiculous johnny, scribbling notes on the back of a mattress-pad wrapper. Scribbling and waiting and wiggling her bare toes. They wouldn’t give her back her phone; she’d had to cajole and threaten just to get a lead pencil.

She was about to buzz again when finally her nurse walked in the door. Joan turned on her get-me-results smile. “Hi, yes, there you are. I was wondering. What was the doctor’s name who was in here?”

“He’s not a doctor from the hospital.”

“I realize that. I was asking his name.”

“His name is Dr. Goodweather.”

“Goodweather.” She scribbled that down. “First name?”

“Doctor.” Her flat smile. “They all have the same first name to me—Doctor.”

Joan squinted as if she wasn’t sure she’d heard that right, and shifted a bit on the stiff sheets. “And he was dispatched here from the Centers for Disease Control?”

“I guess so, yes. He left orders for a number of tests—”

“How many others survived the crash?”

“Well, there was no crash.”

Joan smiled. Sometimes you had to pretend that English was their second language in order to make yourself understood. “What I am asking you is, how many others did not perish on Flight 753 from Berlin to New York?”

“There are three others in this wing with you. Now, Dr. Goodweather wants to take blood and …”

Joan tuned her out right there. The only reason she was still sitting in this sickroom was because she knew she could find out more by playing along. But that ploy was nearing its end. Joan Luss was a tort attorney, “tort” being a legal term meaning “a civil wrong,” recognized as grounds for a lawsuit. A plane full of passengers all die, except for four survivors—one of whom is a tort attorney.

Poor Regis Air. As far as they would be concerned, the wrong passenger had lived.

Joan said, talking right over the nurse’s instructions, “I would like a copy of my medical report to date, along with a complete list of lab tests already performed, and their results …”

“Mrs. Luss? Are you certain you feel all right?”

Joan had swooned for a moment, but it was just a remnant of whatever had overcome them at the end of that horrible flight. She smiled and shook her head fiercely, asserting herself anew. This anger she was feeling would power her through the next one thousand or so billable hours spent sorting through this catastrophe and bringing this dangerously negligent airline to trial.

She said, “Soon I will feel very well indeed.”

Regis Air Maintenance Hangar

“NO FLIES,” SAID EPH.

Nora said, “What?”

They were standing before rows of crash bags laid out before the airplane. The four refrigerated trucks had pulled inside the hangar, sides respectfully canvassed in black to obscure the fish market signage. Each body had already been identified and assigned a bar-coded toe tag by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of New York. This tragedy was a “closed universe” mass disaster, in their parlance, with a fixed and knowable number of casualties—the opposite of the collapse of the Twin Towers. Thanks to passport scans, passenger manifests, and the intact condition of the remains, identification of the decedents was a simple, straightforward task. Determining the cause of their deaths was to be the real challenge.

The tarp crinkled under the HAZMAT team’s boots as the blue vinyl bags were hoisted by straps at either end and loaded aboard their appointed truck with all solemnity.

Eph said, “There should be flies.” The work lights set up around the hangar showed that the air above the corpses was clear but for a lazy moth or two. “Why aren’t there any flies?”

After death, the bacteria along the digestive tract that, in life, cohabitated symbiotically with the healthy human host, begins to fend for itself. It starts feeding on the intestines, eventually eating its way through the abdominal cavity and consuming the organs. Flies can detect the putrid off-gassing from a decomposing carcass as far as one mile away.

Two hundred and six meals were set out here. The hangar should have been buzzing with pests.

Eph started across the tarp toward where a pair of HAZMAT officers was sealing another crash bag. “Hold on,” he said to them. They straightened and stepped back as Eph knelt and unzipped the seam, exposing the corpse inside.

It was the young girl who had died holding her mother’s hand. Eph had memorized her body’s location on the floor without realizing it. You always remember the children.