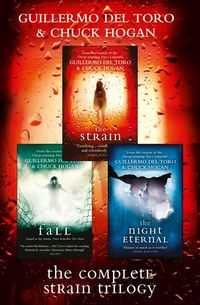

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

The door began lifting off the ground.

Gus was outside before it was halfway up, scuttling up onto the sidewalk like a crab and then quickly catching his breath. He turned and waited, watching the door open, hold there, and then go back down again. He made certain it closed tightly and that nothing emerged.

Then he looked around, shaking off his nerves, checking his hat—and walked to the corner, guilty fast, wanting to put another block between him and the van. He crossed to Vesey Street and found himself standing before the Jersey barriers and construction fences surrounding the city block that had been the World Trade Center. It was all dug out now, the great basin a gaping hole in the crooked streets of Lower Manhattan, with cranes and construction trucks building up the site again.

Gus shook off his chill. He unfolded his phone at his ear.

“Felix, where are you, amigo?”

“On Ninth, heading downtown. Whassup?”

“Nothing. Just get here pronto. I’ve done something I need to forget about.”

Isolation Ward, Jamaica Hospital Medical Center

EPH ARRIVED AT the Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, fuming. “What do you mean they’re gone?”

“Dr. Goodweather,” said the administrator, “there was nothing we could do to compel them to remain here.”

“I told you to post a guard to keep that Bolivar character’s slimy lawyer out.”

“We did post a guard. An actual police officer. He looked at the legal order and told us there was nothing he could do. And—it wasn’t the rock star’s lawyer. It was Mrs. Luss the lawyer. Her firm. They went right over my head, right to the hospital board.”

“Then why wasn’t I told this?”

“We tried to get in touch with you. We called your contact.”

Eph whipped around. Jim Kent was standing with Nora. He looked stricken. He pulled out his phone and thumbed back through his calls. “I don’t see …” He looked up apologetically. “Maybe it was those sunspots from the eclipse, or something. I never got the calls.”

“I got your voice mail,” said the administrator.

He checked again. “Wait … there were some calls I might have missed.” He looked up at Eph. “With so much going on, Eph—I’m afraid I dropped the ball.”

This news hollowed out Eph’s rage. It was not at all like Jim to make any mistake whatsoever, especially at such a critical time. Eph stared at his trusted associate, his anger fizzling out into deep disappointment. “My four best shots at solving this thing just walked out that door.”

“Not four,” said the administrator, behind him. “Only three.”

Eph turned back to her. “What do you mean?”

Inside the isolation ward, Captain Doyle Redfern sat on his bed, inside the plastic curtains. He looked haggard; his pale arms were resting on a pillow in his lap. The nurse said that he had declined all food, claiming stiffness in his throat and persistent nausea, and had rejected even tiny sips of water. The IV in his arm was keeping him hydrated.

Eph and Nora stood with him, masked and gloved, eschewing full barrier protection.

“My union wants me out of here,” said Redfern. “The airline industry policy is, ‘Always blame pilot error.’ Never the airline’s fault, overscheduling, maintenance cutbacks. They’re going to go after Captain Moldes on this one, no matter what. And me, maybe. But—something doesn’t feel right. Inside. I don’t feel like myself.”

Eph said, “Your cooperation is critical. I can’t thank you enough for staying, except to say that we’ll do everything in our power to get you healthy again.”

Redfern nodded, and Eph could tell that his neck was stiff. He probed the underside of his jaw, feeling for his lymph nodes, which were quite swollen. The pilot was definitely fighting off something. Something related to the airplane deaths—or merely something he had picked up over the course of his travels?

Redfern said, “Such a young aircraft, and an all-around beautiful machine. I just can’t see it shutting down so completely. It’s got to be sabotage.”

“We’ve tested the oxygen mix and the water tanks, and both came back clean. Nothing to indicate why people died or why the plane went dark.” Eph massaged the pilot’s armpits, finding more jelly-bean-size lymph nodes there. “You still remember nothing about the landing?”

“Nothing. It’s driving me crazy.”

“Can you think of any reason the cockpit door would be unlocked?”

“None. Completely against FAA regulations.”

Nora said, “Did you happen to spend any time up in the crew rest area?”

“The bunk?” Redfern said. “I did, yeah. Caught a few z’s over the Atlantic.”

“Do you remember if you put the seat backs down?”

“They were already down. You need the leg room if you’re stretching out up there. Why?”

Eph said, “You didn’t see anything out of the ordinary?”

“Up there? Not a thing. What’s to see?”

Eph stood back. “Do you know anything about a large cabinet loaded into the cargo area?”

Captain Redfern shook his head, trying to puzzle it out. “No idea. But it sounds like you’re on to something.”

“Not really. Still as baffled as you are.” Eph crossed his arms. Nora had switched on her Luma light and was going over Redfern’s arms with it. “Which is why your agreeing to stay is so critical right now. I want to run a full battery of tests on you.”

Captain Redfern watched the indigo light shine over his flesh. “If you think you can figure out what happened, I’ll be your guinea pig.”

Eph nodded their appreciation.

“When did you get this scar?” asked Nora.

“What scar?”

She was looking at his neck, the front of his throat. He tipped his head back so that she could touch the fine line that showed up deep blue under her Luma. “Looks almost like a surgical incision.”

Redfern felt for it himself. “There’s nothing.”

Indeed, when she switched off the lamp, the line was all but invisible. She turned it back on and Eph examined the line. Maybe a half inch across, a few millimeters thick. The tissue growth over the wound appeared quite recent.

“We’ll do some imaging later tonight. MRI should show us something.”

Redfern nodded, and Nora turned off her light wand. “You know … there is one other thing.” Redfern hesitated, his airline pilot’s confidence fading for a moment. “I do remember something, but it won’t be of any use to you, I don’t think …”

Eph shrugged almost imperceptibly. “We’ll take anything you can give us.”

“Well, when I blacked out … I dreamed of something—something very old …” The captain looked around, almost ashamedly, then started talking in a very low voice. “When I was a kid … at night … I used to sleep in this big bed in my grandmother’s home. And every night, at midnight, as the bells chimed in the church nearby, I used to see a thing come out from behind a big old armoire. Every night, without fail—it would poke out its black head and long arms and bony shoulders … and stare at me …”

“Stare?” asked Eph.

“It had a jagged mouth, with thin, black lips … and it would look at me, and just … smile.”

Eph and Nora were both transfixed, the intimacy of the confession and its dreamlike tone both unexpected.

“And then I would start screaming, and my grandmother would turn on the light and take me to her bed. It went on for years. I called him Mr. Leech. Because his skin … that black skin looked just like the engorged leeches we used to pick up in a nearby stream. Child psychiatrists looked at me and talked to me and called it ‘night terrors’ and gave me reasons not to believe in him, but … every night he came back. Every night I would sink under my pillows, hiding from him—but it was useless. I knew he was there, in the room …” Redfern grimaced. “We moved out some years later and my grandmother sold the armoire and I never saw it again. Never dreamed of it again.”

Eph had listened carefully. “You’ll have to excuse me, Captain … but what does this have to do with …?”

“I’m coming to that,” he said. “The only thing I remember between our descent and waking up here—is that he came back. In my dreams. I saw him again, this Mr. Leech … and he was smiling.”

INTERLUDE II The Burning Hole

HIS NIGHTMARES WERE ALWAYS THE SAME: ABRAHAM, OLD or young, naked and kneeling before the huge hole in the ground, the bodies burning below as a Nazi officer moved down the row of kneeling prisoners, shooting them in the back of the head.

The burning hole was behind the infirmary in the extermination camp known as Treblinka. Prisoners too sick or too old to work were taken through the white-painted barracks with a red cross painted on it, and into the hole they went. Young Abraham saw many die there, but he himself came close to it only once.

He tried to avoid notice, worked in silence, and kept to himself. Each morning he pricked his finger and smeared a drop of blood on each cheek in order to appear as healthy as possible at roll call.

He first saw the hole while repairing some shelving in the infirmary. At age sixteen, Abraham Setrakian was a yellow patch, a craftsman. He curried no favor; he was no one’s pet, merely a slave with a talent for woodwork that, in a death camp, was a talent for living. He had some value for the Nazi Hauptmann who used him without mercy, without regard, and without end. He raised barbed-wire fences, crafted a library set, repaired the railways. He carved elaborate pipes for the Ukrainian guard captain at Christmastime in ’42.

It was his hands that kept Abraham away from the hole. At dusk he could see its glow, and sometimes from his workshop the smell of flesh and petrol mixed with sawdust. As his fear took hold of his heart, so did the hole take residence there.

To this day, Setrakian still felt it in him, every time fear took hold—whether crossing a dark street, closing his shop at night, or upon waking from the nightmares—the tatters of his memories revived. Himself kneeling, naked, praying. In his dreams he could feel the mouth of the gun pressing against his neck.

Extermination camps had no function other than killing. Treblinka was disguised to look like a train station, with travel posters and timetables, and greenery woven into the barbed wire. He arrived there in September 1942 and spent all of his time working. “Earning his breath,” he called it. He was a quiet man, young but well raised, full of wisdom and compassion. He helped as many prisoners as he could and prayed in silence all the time. Even with the atrocities he witnessed daily, he believed that God was watching over all men.

But one winter night, in the eyes of a dead thing, Abraham saw the devil. And understood the ways of the world to be different from what he’d thought.

It was past midnight and the camp was as quiet as Setrakian ever saw it. The forest murmur had quieted down and the cold air was splitting his bones. He shifted quietly in his bunk and gazed blindly at the darkness surrounding him. And then he heard it—

Pick-pick-pick.

Exactly as his bubbeh had said … it sounded exactly as she’d said … and for some reason that made it all the more frightful …

His breath vanished and he felt in his heart the burning hole. In a corner of the barracks, the darkness moved. A Thing, a towering gaunt figure peeled off from the inky depths and glided over his sleeping comrades.

Pick-pick-pick.

Sardu. Or a Thing that once had been him. Its skin was shriveled and dark, blending with the fold of its dark, loose robes. Much like an animated blotch of ink. The Thing moved effortlessly, a weightless phantom gliding across the floor. Its talonlike toenails scraped the wood ever so softly.

But—it couldn’t be. The world was real—evil was real, and surrounding him all the time—but this could not be real. This was a bubbeh meiseh. A bubbeh—

Pick-pick-pick …

In a matter of seconds, the long-dead Thing reached the bunk across from Setrakian. Abraham could smell it now: dried leaves and earth and mold. He could see hints of its blackened face as it emerged from the bundled darkness of the body—and leaned forward, smelling the neck of Zadawski, a young Pole, a hard worker. The Thing stood the height of the barracks, its head among the beams above, breathing hard and hollowly, excited, hungry. It moved along to the next bunk, where its face was briefly outlined by the light of a nearby window.

The darkened skin became translucent, like a sliver of dry meat against the light. It was all dry and matte—except for its eyes: two gleaming spheres that seemed to glow intermittently, like lumps of burning coal catching a reanimating breath. Its dry lips drew back to reveal mottled gums and two rows of small, yellowed teeth, impossibly sharp.

It paused above the frail form of Ladizlav Zajak, an old man from Grodno, a late arrival sickened with tuberculosis. Setrakian had supported Zajak since his arrival, showing him the ropes and shielding him from scrutiny. His disease alone was reason enough for instant execution—but Setrakian claimed him as his assistant, and kept him away from the SS overseers and Ukrainian guards at critical times. But Zajak was gone now. His lungs were giving out, and, more important, he had lost the will to live: shutting down, seldom speaking, constantly crying in silence. He had become a liability to Setrakian’s survival, but his entreaties no longer inspired the old man—Setrakian hearing him shudder with silent coughing spasms and quietly sobbing until dawn.

But now, towering above him, the Thing observed Zajak. The arrhythmic breathing of the old man seemed to please it. Like the angel of death, it extended its darkness over the man’s frail body and clucked its dry palate eagerly.

What the Thing did then … Setrakian could not see. There was noise, but his ears refused to hear it. This great, gloating Thing bent over the old man’s head and neck. Something about its posture indicated … a feeding. Zajak’s old body twitched and spasmed ever so lightly, but, remarkably, the old man never awoke.

And never did again.

Setrakian muffled a gasp with his hand. And the feeding Thing didn’t seem to mind him. It spent time over the various sick and infirm. By night’s end, three corpses were left behind, and the thing looked flushed—its skin suppler but equally dark.

Setrakian saw the Thing fade away into the darkness and leave. Cautiously, he got up and moved next to the bodies. He looked them over in the faint light, and there was no sign of any trauma—other than a thin slit in the neck. A breach so thin as to be nearly imperceptible. If he hadn’t witnessed the horror himself …

Then it dawned on him. This Thing. It would return again—and soon. This camp was a fertile feeding ground, and it would graze on the unnoticed, the forgotten, the inconsequential. It would feed on them. All of them.

Unless someone rose up to stop it.

Someone.

Him.

Coach

Flight 753 survivor Ansel Barbour huddled with his wife, Ann-Marie, and his two children, eight-year-old Benjy and five-year-old Haily, on a blue chintz sofa in the back sunroom of their three-bedroom home in Flatbush, New York. Even Pap and Gertie got into the act, the two big Saint Bernards allowed inside the house for this special occasion, so happy to see him home, their man-size paws leaning on his knees and patting gratefully at his chest.

Ansel had been seated in aisle seat 39G, in coach, returning home from an employer-paid database security training session in Potsdam, southwest of Berlin. He was a computer programmer embarking on a four-month contract with a New Jersey – based retailer following the electronic theft of millions of customers’ credit card numbers. He had never been out of the country before, and had missed his family intensely. Downtime and sightseeing tours were built into the four-day conference, but Ansel never ventured outside his hotel, preferring to remain inside his room with his laptop, talking to the kids via Webcam and playing hearts over the Internet with strangers.

His wife, Ann-Marie, was a superstitious, sheltered woman, and Flight 753’s tragic end only confirmed her closely held fears of air travel and new experiences in general. She did not drive a car. She lived in the grip of dozens of borderline obsessive-compulsive routines, including touching and repetitively cleaning every mirror in the house, which reliably warded off bad luck. Her parents had died in an automobile accident when she was four—she’d survived the crash—and she was raised by an unmarried aunt who passed away just one week before Ann-Marie and Ansel’s wedding. The births of her children had only intensified Ann-Marie’s isolation, amplifying her fears, to the point where she would often go days without leaving the safety of her own house, relying exclusively on Ansel for anything involving a transaction with the outside world.

The news of the crippled airplane had brought her to her knees. Ansel’s subsequent survival revived her with the power of an exultation that she could define only in religious terms, a deliverance confirming and consecrating the absolute necessity of her redundant, life—preserving routines.

Ansel, for his part, was intensely relieved to be back home. Both Ben and Haily tried to pile on top of him, but he had to hold them off due to the lingering pain in his neck. The tightness—his muscles felt like ropes being torturously twisted—was centralized in his throat, but extended past the hinges of his jaw up to his ears. When you twist a rope, it shortens, and that was how his muscles felt. He stretched his neck, hoping for some chiropractic relief—

SNAP … CRACKLE … POP …

—which nearly doubled him over. The pain wasn’t worth the effort.

Later, Ann-Marie walked in on him in the kitchen as he was replacing her economy-size bottle of ibuprofen in the high cabinet over the stove. He popped six at once, the daily recommended dosage—and was barely able to get them down.

Her fearful eyes drained of all cheer. “What is it?”

“Nothing,” he said, though he was in too much discomfort to shake his head. But best not to worry her. “Just stiffness from the plane. The way my head hung, probably.”

She remained in the doorway, pulling at her fingers. “Maybe you shouldn’t have left the hospital.”

“And how would you have been able to get by?” he shot back, being shorter with her than he’d planned.

SNAP, CRACKLE, AND POP—

“But what if … what if you have to go back in? What if, this time, they want you to stay?”

It was exhausting, having to dismiss her fears at the expense of his own. “I can’t miss any work as it is. You know we’re right on the edge with our finances.”

They were a one-income household in an America of two-income households. And Ansel couldn’t take a second job, because then who would do the grocery shopping?

She said, “You know I … I couldn’t get along without you.” They never discussed her illness. At least, never in terms of it being an illness. “I need you. We need you.”

Ansel’s shoulder nod was more like a bow, dipping at his waist instead of his neck. “My God, when I think about all those people.” He pictured his seatmates from the long flight. The family with three grown children two rows in front of him. The older couple sitting across the aisle, sleeping most of the way, white-haired heads sharing the same travel pillow. The bleached-blonde flight attendant who dripped diet soda on his lap. “Why me, you know? Is there some reason I survived?”

“There is a reason,” she said, her hands flat against her chest. “Me.”

Later, Ansel took the dogs back out to their backyard shed. The yard was the main reason they’d bought this house: plenty of play room for the kids and the dogs. Ansel had Pap and Gertie before he’d ever met Ann-Marie, and she had fallen in love with them at least as much as she had him. They loved her back, no conditions. As did Ansel, and as did the kids—although Benjy, the older one, was starting to question her eccentricities here and there. Especially when they caused a conflict with an eight-year-old’s schedule of baseball practices and play dates. Already Ansel could sense Ann-Marie pulling back from him a bit. But Pap and Gertie would never challenge her, so long as she kept overfeeding them. He feared for the kids as they grew up, feared that they might outgrow their mother at too early an age, and never truly understand why she might appear to favor the dogs over them.

Inside the old garden shed, a metal fence pole was driven into the center floorboards, with two chains attached to it. Gertie had run off earlier that year, coming back with switch marks all over her back and legs, somebody having taken a whipping stick to her. So they chained up the dogs at night now, for their own protection. Ansel slowly—keeping his neck and head aligned, minimizing discomfort—set down their food and water, then ran his hand over the tufts of their enormous heads as they ate, just making them real, appreciating them for what they were at the end of this lucky day. He went out and closed the door after chaining them to the pole, and stood looking at his house from the back, trying to imagine this world without him in it. Ansel had seen his children weep today, and he had wept with them. His family needed him more than anything.

A sudden, piercing pain in his neck shook him. He grabbed for the corner of the dog shed in order to keep from falling over, and for several moments stood frozen like that, doubled over to one side, shivering and riding out this flaring, knifing pain. It passed finally, leaving him with a seashell-like roaring in one ear. He probed his neck gently with his fingers, too tender to touch. He tried to stretch it, to improve his mobility, tipping his head back as far as he could toward the night sky. Airplane lights up there, stars.

I survived, he thought. The worst is over. This soon will pass.

That night he had a horrifying dream. His children were being chased through the house by some rampaging beast, but when Ansel ran to save them, he found he had monster claws for hands. He woke up with his half of the bed soaked in sweat, and climbed out quickly—only to be gripped by another seizure of pain.

SNAP

His ears, jaw, and throat were fused together by the same taut ache, leaving him unable to swallow.

CRACKLE

The pain of that basic esophageal retraction was nearly crippling.

And then there was the thirst. Like nothing he had ever felt—an urge that would not stop.

When he could move again, he walked across the hall and into the dark kitchen. He opened the fridge and poured himself a tall glass of lemonade, then another, and another … and soon he was drinking straight from the pitcher. But nothing would quench the thirst. Why was he sweating so much?

The stains on his nightshirt had a heavy odor—vaguely musky—and the sweat had an amber tint. So hot in here …

As he placed the pitcher back in the fridge, he spotted a plate with marinating meat. He saw the sinuous strands of blood mixing lazily with oil and vinegar, and his mouth watered. Not at the prospect of grilling it, but at the idea of biting it—of sinking his teeth into it and tearing it and draining it. At the idea of drinking the blood.

POP

He wandered into the main hallway and took a peek at the kids. Benjy was balled up under Scooby-Doo sheets; Haily was snoring softly with her arm dangling off the side of her mattress, reaching for picture books that had fallen there. Seeing them allowed him to relax his shoulders and catch his breath a bit. He stepped out into the backyard to cool off, the night air chilling the dried sweat on his skin. Being home, he felt, being with his family, could cure him of anything. They would help him.