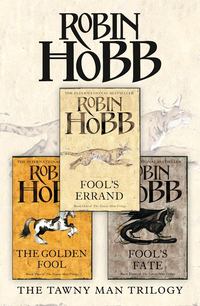

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

The Fool was filling the teapot with steaming water. ‘It’s the way of my kind,’ he said quietly. ‘Our lives are longer, so we progress through them more slowly. I’ve changed, Fitz, even if all you see is the colour of my flesh. When last you saw me, I was just approaching adulthood. All sorts of new feelings and ideas were blossoming in me, so many that I scarce could keep my mind on the tasks at hand. When I recall how I behaved, well, even I am scandalized. Now, I assure you, I am far more mature. I know that there is a time and place for everything, and that what I am destined to do must take full precedent over anything I might long to do for myself.’

I poured the beaten eggs into a pan and set them at the fire’s edge. I spoke slowly. ‘When you speak in riddles, it exasperates me. Yet when you try to speak clearly of yourself, it frightens me.’

‘All the more reason why I should not speak of myself at all,’ he exclaimed with false heartiness. ‘Now. What be our tasks for the day?’

I thought it out as I stirred the setting eggs and pushed them closer to the fire. ‘I don’t know,’ I said quietly.

He looked startled at the sudden change in my voice. ‘Fitz? Are you all right?’

I myself could not explain the sudden lurch in my spirits. ‘Suddenly, it all seems so pointless. When I knew Hap was going to be here for the winter, I always took care to provide for us both. My garden was a quarter that size when the boy first came to me, and Nighteyes and I hunted day to day for our meat. If we did not hunt well and went empty for a day or so, it did not seem of much consequence. Now, I look at all I have already set by and think, if the boy is not here, if Hap is wintering with a master while he starts to learn his trade, why, then I already have plenty for both Nighteyes and me. Sometimes it seems that there’s no point to it. And then I wonder if there’s any point left to my life at all.’

A frown divided the Fool’s brows. ‘How melancholy you sound. Or is this the elfbark I’m hearing?’

‘No.’ I took up the shirred eggs and brought them to the table. It was almost a relief to speak the thoughts I’d been denying. ‘I think it was why Starling brought Hap to me. I think she saw how aimless my life had become, and brought me someone to give shape to my days.’

The Fool set down plates with a clatter, and dished food onto them in disgusted splats. ‘I think you give her credit for thinking of something beyond her own needs. I suspect she picked up the boy on an impulse, and dumped him here when she wearied of him. It was just lucky for both of you that you helped each other.’

I said nothing. His vehemence in his dislike for Starling surprised me. I sat down at the table and began eating. But he had not finished.

‘If Starling meant for anyone to give shape to your days, it was herself. I doubt that she ever imagined you might need anyone’s companionship other than hers.’

I had an uncomfortable suspicion he was right, especially when I recalled how she had spoken of Nighteyes and Hap on her last visit.

‘Well. What she thought or didn’t think scarcely matters now. One way or another, I’m determined to see Hap apprenticed well. But once I do –’

‘Once you do, you’ll be free to take up your own life again. I’ve a feeling it will call you back to Buckkeep.’

‘You’ve “a feeling”?’ I asked him dryly. ‘Is this a Fool’s feeling, or a White Prophet’s feeling?’

‘As you never seemed to give credence to any of my prophecies, why should you care?’ He smiled archly at me and began eating his eggs.

‘A time or three, it did seem as if what you predicted came true. Though your predictions were always so nebulous, it seemed to me that you could make them mean anything.’

He swallowed. ‘It was not my prophecies that were nebulous, but your understanding of them. When I arrived, I warned you that I had come back into your life because I must, not because I wanted to. Not that I didn’t want to see you again. I mean only that if I could spare you somehow from all we must do, I would.’

‘And what is it, exactly, that we must do?’

‘Exactly?’ he queried with a raised eyebrow.

‘Exactly. And precisely,’ I challenged him.

‘Oh, very well, then. Exactly and precisely what we must do. We must save the world, you and I. Again.’ He leaned back, tipping his chair onto its back legs. His pale brows shot towards his hairline as he widened his eyes at me.

I lowered my brow into my hands. But he was grinning like a maniac and I could not contain my own smile. ‘Again? I don’t recall that we did it the first time.’

‘Of course we did. You’re alive, aren’t you? And there is an heir to the Farseer throne. Hence, we changed the course of all time. In the rutted path of fate, you were a rock, my dear Fitz. And you have shifted the grinding wheel out of its trough and into a new track. Now, of course, we must see that it remains there. That may be the most difficult part of all.’

‘And what, exactly and precisely, must we do to ensure that?’ I knew his words were bait for mockery, but as ever, I could not resist the question.

‘It’s quite simple.’ He ate a bite of eggs, enjoying my suspense. ‘Very simple, really.’ He pushed the eggs around on his plate, scooped up a bite, then set his spoon down. He looked up at me, and his smile faded. When he spoke, his voice was solemn. ‘I must see that you survive. Again. And you must see that the Farseer heir inherits the throne.’

‘And the thought of my survival makes you sad?’ I demanded in perplexity.

‘Oh, no. Never that. The thought of what you must go through to survive fills me with foreboding.’

I pushed my plate away, my appetite fled. ‘I still don’t understand you,’ I replied irritably.

‘Yes, you do,’ he contradicted me implacably. ‘I suppose you say you don’t because it is easier that way, for both of us. But this time, my friend, I will lay it cold before you. Think back on the last time we were together. Were there not times when death would have been easier and less painful than life?’

His words were shards of ice in my belly, but I am nothing if not stubborn. ‘Well. And when is that ever not true?’ I demanded of him.

There have been very few times in my life when I have been able to shock the Fool into silence. That was one of them. He stared at me, his strange eyes getting wider and wider. Then a grin broke over his face. He stood so suddenly he nearly overset his chair, and then lunged at me to seize me in a wild hug. He drew a deep breath as if something that had constricted him had suddenly sprung free. ‘Of course that is true,’ he whispered by my ear. And then, in a shout that near deafened me, ‘Of course it is!’

Before I could shrug free of his strangling embrace, he sprang apart from me. He cut a caper that made motley of his ordinary clothes, and then sprang lightly to my tabletop. He flung his arms wide as if he once more performed for all of King Shrewd’s court rather than an audience of one. ‘Death is always less painful and easier than life! You speak true. And yet we do not, day to day, choose death. Because ultimately, death is not the opposite of life, but the opposite of choice. Death is what you get when there are no choices left to make. Am I right?’

Infectious as his fey mood was, I still managed to shake my head. ‘I have no idea if you are right or wrong.’

‘Then take my word for it. I am right. For am I not the White Prophet? And are not you my Catalyst, who comes to change the course of all time? Look at you. Not the hero, no. The changer. The one who, by his existence, enables others to be heroes. Ah, Fitz, Fitz, we are who we are and who we ever must be. And when I am discouraged, when I lose heart to the point of saying, “but why cannot I leave him here, to find what peace he may?”, then, lo and behold, you speak with the voice of the Catalyst, and change my perception of all that I do. And enable me to be once more what I must be. The White Prophet.’

I sat looking up at him. Despite my efforts, a smile twisted my mouth. ‘I thought I enabled other people to be heroes. Not prophets.’

‘Ah, well.’ He leapt lightly to the floor. ‘Some of us must be both, I fear.’ He gave himself a shake, and tugged his jerkin straight. Some of the wildness went out of him. ‘So. To return to my original question. What are our tasks today? My turn to give you the answer. Our first task today is to give no thought to the morrow.’

I took his advice, for that day at least. I did things I had not been giving myself permission to do, for they were not the serious tasks that provided against the morrow, but the simple work that brought me pleasure. I worked on my inks, not to take to market and sell for coin, but to try to create a true purple for my own pleasure. It yielded no success that day; all my purples turned to brown as they dried, but it was a work I enjoyed. As for the Fool, he amused himself by carving on my furniture. I glanced up at the sound of my kitchen knife scraping across wood. The movement caught his eye. ‘Sorry,’ he apologized at once. He held the knife up between two fingers to show me, and then carefully set it down. He got up from his chair and wandered over to his saddlepack. After a moment of digging, he tugged out a roll of fine bladed tools. Humming to himself, he went back to the table and set to on the chairs. He went bare-fingered to his task, tugging off the fine glove that usually masked his Skill-hand. As the day progressed, my simple chairs gained leafy vines twining up their backs, and occasional little faces peeping out of the foliage.

When I looked up from my work in mid-afternoon, I saw him come in with chunks of seasoned wood from my woodpile. I leaned back from my desk to watch him as he turned and considered each one, studying them and tracing their grain with his Skill-fingers as if he could read their secrets hidden from my eyes. At length he selected one with a knee in it and started in on it. He hummed to himself as he worked, and I left him to it.

Nighteyes woke once during the day. He clumped down from my bed with a sigh and tottered outside. I offered him food when he returned but he turned his nose up at it. He had drunk deeply, all the water he could hold, and he lay himself down with a sigh on the cool floor of the cabin. He slept again, but not as deeply.

And so I passed that day in pleasure, which is to say, in the sort of work I wanted to do rather than the work that I thought I ought to be doing. Chade came often to my mind that day. I wondered, as I seldom had before, at how the old assassin had passed his long hours and days up in his isolated tower before I had come to be his apprentice. Then I sniffed disdainfully at that image of him. Long before I had arrived, Chade had been the royal assassin, bearing the King’s Justice in the form of quiet work wherever it needed to go. The sizeable library of scrolls in his apartments and his endless experiments with poisons and deadly artifice were proof that he had known how to occupy his days. And he had had the welfare of the Farseer reign to give him a purpose in life.

Once, I, too, had shared that purpose. I had shrugged free of it to have a life of my own. Odd, that in the process I had somehow wrenched myself free of the very life I had thought to have to myself. To gain the freedom to enjoy my life, I had severed all connections with that old life. I had lost contact with all who had loved me and all I had loved.

That wasn’t the complete truth, but it suited my mood. An instant later, I realized I was wallowing in self-pity. My last three attempts at a purple ink were drying to brown, though one did have a very nice shade of rose to the brown. I set aside that scrap of paper, after making notes on it as to how I had got the colour. It would be good ink for botanical illustrations, I thought.

I unfolded my legs from my chair and rose, stretching. The Fool looked up from his work. ‘Hungry?’ I asked him.

He considered a moment. ‘I could eat. Let me cook. The food you make fills the stomach but does little more than that.’

He set aside the figurine he was working on. He saw me glance at it, and covered it, almost jealously. ‘When I’m finished,’ he promised, and began a purposeful ransacking of my cupboards. While he was tsk-ing over my lack of any interesting spices, I wandered outside. I crossed the stream, which could have led me gently down to the beach. Idly I walked up the hill, past both horse and pony grazing freely. At the crest of the hill I walked more slowly until I reached my bench. I sat down on it. Only a few steps away, the grassy hill gave way to sudden slate cliffs and the rocky beach below them. Seated on my bench, all I could see was the wide vista of ocean spread out before me. Restlessness walked through my bones again. I thought of my dream of the boy and the hunting cat out in the night and smiled to myself. Run away from it all, the cat had urged the boy, and the thought had all my sympathy.

Yet, years ago, that was what I had done, and this was what it had brought me. A life of peace and self-sufficiency, a life that should have satisfied me; yet, here I sat.

A time later, the Fool joined me. Nighteyes, too, came at his heels, to lie down at my feet with a martyred sigh. ‘Is it the Skill-hunger?’ the Fool asked with quiet sympathy.

‘No,’ I replied, and almost laughed. The hunger he had unknowingly waked in me yesterday was temporarily crippled by the elfbark I had consumed. I might long to Skill, but right now my mind was numbed to that ability.

‘I’ve put dinner to cook slow over a little fire, to keep from driving us out of the house. We’ve plenty of time.’ He paused, and then asked carefully, ‘And after you left the Old Blood folk, where did you go?’

I sighed. The wolf was right. Talking to the Fool did help me to think. But perhaps he made me think too much. I looked back through the years and gathered up the threads of my tale.

‘Everywhere. When we left there, we had no destination. So we wandered.’ I stared out across the water. ‘For four years, we wandered, all through the Six Duchies. I’ve seen Tilth in winter, when snow but a few inches deep blows across the wide plains but the cold seems to go down to the earth’s very bones. I crossed all of Farrow to reach Rippon, and then walked on to the coast. Sometimes I took work as a man, and bought bread, and sometimes the two of us hunted as wolves and ate our meat dripping.’

I glanced over at the Fool. He listened, his golden eyes intent on my story. If he judged me, his face gave no sign of it.

‘When we reached the coast, we took ship north, although Nighteyes did not enjoy it. I visited Bearns Duchy in the depth of one winter.’

‘Bearns?’ He considered that. ‘Once, you were promised to Lady Celerity of Bearns Duchy.’ The question was in his face but not his voice.

‘That was not of my will, as you recall. I did not go there to seek out Celerity. But I did glimpse Lady Faith, Duchess of Bearns, as she rode through the streets on her way to Ripplekeep Castle. She did not see me, and if she had, I am sure she would not have recognized the ragged wanderer as Lord FitzChivalry. I hear that Celerity married rich in both love and lands, and is now the Lady of Ice Towers near Ice Town.’

‘I am glad for her,’ the Fool said gravely.

‘And I. I never loved her, but I admired her spirit, and liked her well enough. I am glad of her good fortune.’

‘And then?’

‘I went to the Near Islands. From there, I wished to make the long crossing to the Out Islands, to see for myself the land of the folk who had raided and made us miserable for so long, but the wolf refused to even consider such a long sea journey.

‘So we returned to the mainland, and travelled south. We went mostly by foot though we took ship past Buckkeep and did not pause there. We journeyed down the coast of Rippon and Shoaks, and on beyond the Six Duchies. I didn’t like Chalced. We took ship from there just to get away from it.’

‘How far did you go?’ the Fool prompted when I fell silent.

I felt my mouth twist in a grin as I bragged, ‘All the way to Bingtown.’

‘Did you?’ His interest heightened. ‘And what did you think of it?’

‘Lively. Prosperous. It put me in mind of Tradeford. The elegant people and their ornate houses, with glass in every window. They sell books in street booths there, and in one street of their market, every shop has its own sort of magic. Just to walk down that way dizzied me. I could not tell you what kind of magic it was, but it pressed against my senses, giddying me like too strong perfume …’ I shook my head. ‘I felt like a backward foreigner, and no doubt so they thought me, in my rough clothes with a wolf at my side. Yet, despite all I saw there, the city couldn’t live up to the legend. What did we used to say? That if a man could imagine a thing, he could find it for sale in Bingtown. Well, I saw much there that was far beyond my imagining, but that didn’t mean it was something I’d want to buy. I saw great ugliness there, too. Slaves coming off a ship, with great cankers on their ankles from the chains. We saw one of their talking ships, too. I had always thought them just a tale.’ I grew silent for a moment, wondering how to convey what Nighteyes and I had sensed about that grim magic. ‘It wasn’t a magic I’d ever be comfortable around,’ I said at last.

The sheer humanity of the city had overwhelmed the wolf, and he was happy to leave as soon as I suggested it. I felt smaller after my visit there. I appreciated anew the wildness and isolation of Buck’s coast, and the rough militancy of Buckkeep. I had once thought Buckkeep the heart of all civilization, but in Bingtown they spoke of us as barbaric and rude. The comments I overheard stung, and yet I could not deny them. I left Bingtown a humbled man, resolved to add to my education and better discover the true width of the world. I shook my head at that recollection. Had I ever lived up to my resolve?

‘We didn’t have the money for ship passage, even if Nighteyes could have faced it. We decided to journey up the coast on foot.’

The Fool turned an incredulous face to me. ‘But you can’t do that!’

‘That’s what everyone warned us. I thought it was city talk, a warning from folk who had never travelled hard and rough. But they were right.’

Against all counsel, we attempted to travel by foot up the coastline. In the wild lands outside of Bingtown, we found strangeness that near surpassed what we had discovered beyond the Mountain Kingdom. Well is that coast called the Cursed Shores. I was tormented by half-formed dreams, and sometimes my wakened imaginings were giddy and threatening. It distressed the wolf that I walked on the edges of madness. I can offer no reason for this. I suffered no fevers nor any of the other symptoms of the illnesses that can unseat a man’s mind, yet I was not myself as we passed through that rough and inhospitable country. Vivid dreams of Verity and our dragons came back to haunt me. Even awake, I tormented myself endlessly with the foolishness of past decisions, and thought often of ending my own life. Only the companionship of the wolf kept me from such an act. Looking back, I recall, not days and nights, but a succession of lucid and disturbing dreams. Not since I had first travelled on the Skill-road had I suffered such a contortion of my own thoughts. It is not an experience I would willingly repeat.

Never, before or since, had I seen a stretch of coast as devoid of humanity. Even the animals that lived there rang sharp and odd against my Wit-sense. The physical aspects of this coast were as foreign to us as the savour of it. There were bogs that steamed and stank and burned our nostrils, and lush marshes where all the plant life seemed twisted and deformed despite its rank and luxuriant growth. We reached the Rain River, which the folk of Bingtown call the Rain Wild River. I cannot say what distorted whim persuaded me to follow it inland, but I attempted it. The swampy shores, rank growth, and strange dreams of the place soon turned us back. Something in the soil ate at Nighteyes’ pads and weakened the tough leather boots I wore until they were little more than tatters. We admitted ourselves defeated, but then added a greater error to our wayward quest when we cut young trees to fashion a raft. Nighteyes’ nose had warned us against drinking any of the river water, but I had not fully appreciated what a danger it presented to us. Our makeshift raft barely lasted to carry us back to the mouth of the river, and we both incurred ulcerating sores from the touch of the water. We were relieved to get back to good honest salt water. Despite the sting of it, it proved most healing to our sores.

Although Chalced has long claimed rightful domain of the land up to the Rain River, and has frequently asserted that Bingtown, too, lies within its reign, we saw no signs of any settlements on that coast. Nighteyes and I travelled a long and inhospitable way north. Three days past the Rain River, we seemed to leave the strangeness behind, but we journeyed another ten days before we encountered a human settlement. By then, regular washing in brine had healed much of our sores, and my thoughts seemed more my own, but we presented the aspect of a weary beggar and his mangy dog. Folk were not welcoming to us.

My footsore journey north through Chalced persuaded me that folk there are the most inimical in the world. I enjoyed Chalced fully as much as Burrich had led me to believe I would. Even their magnificent cities could not move me. The wonders of its architecture and the heights of its civilization are built on a foundation of human misery. The reality of widespread slavery appalled me.

I paused in my tale to glance at the freedom earring that hung from the Fool’s ear. It had been Burrich’s grandmother’s hard-won prize, the mark of a slave who had won freedom. The Fool lifted a hand to touch it with a finger. It hung next to several others carved of wood, and its silver network caught the eye.

‘Burrich,’ the Fool said quietly. ‘And Molly. I ask you directly this time. Did you ever seek them out?’

I hung my head for a moment. ‘Yes,’ I admitted after a time. ‘I did. It is odd you should ask now, for it was as I crossed Chalced that I was suddenly seized with the urge to see them.’

One evening as we camped well away from the road, I felt my sleep seized by a powerful dream. Perhaps the images came to me because in some corner of her heart, Molly kept still a place for me. Yet I did not dream of Molly as a lover dreams of his beloved. I dreamed of myself, I thought, small and hot and deathly ill. It was a black dream, a dream all of sensations without images. I lay curled tight against Burrich’s chest, and his presence and smell were the only comforts I knew in my misery. Then unbearably cool hands touched my fevered skin. They tried to lift me away, but I wriggled and cried out, clinging to him. Burrich’s strong arm closed around me again. ‘Leave her be,’ he commanded hoarsely.

I heard Molly’s voice from a distance, wavering and distorted. ‘Burrich, you’re as sick as she is. You can’t take care of her. Let me have her while you rest.’

‘No. Leave her beside me. You take care of Chiv and yourself.’

‘Your son is fine. Neither of us is ill. Only you and Nettle. Let me take her, Burrich.’

‘No,’ he groaned. His hand settled on me protectively. ‘This is how the Blood Plague began, when I was a boy. It killed everyone I loved. Molly, I couldn’t bear it if you took her away from me and she died. Please. Leave her beside me.’

‘So you can die together?’ she demanded, her weary voice going shrill.

There was terrible resignation in his voice. ‘If we must. Death is colder when it finds you alone. I will hold her to the last.’

He was not rational, and I felt both Molly’s anger and her fear for him. She brought him water, and I fussed when she half-sat him up to drink it. I tried to drink from the cup she held to my mouth, but my lips were cracked and sore, my head hurt too badly and the light was too bright. When I pushed it away, the water slopped on my chest, icy cold and I shrieked and began to wail. ‘Nettle, Nettle, hush,’ she bade me, but her hands were cold when she touched me. I wanted nothing of my mother just then, and knew an echo of Nettle’s jealousy that another child claimed the throne of Molly’s lap now. I clutched at Burrich’s shirt and he held me close again and hummed softly in his deep voice. I pushed my face against him where the light could not touch my eyes, and tried to sleep.