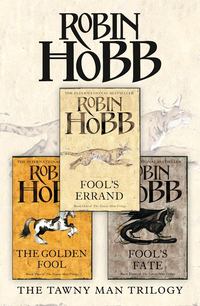

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

‘Folk did not use to live there,’ I said. I bit my tongue before I added that Prince Verity had loved to hunt these hills. I doubted they offered much game any more. Trees had been cleared to allow small gardens to be cultivated. Donkeys and ponies grazed in brushy pastures.

Laurel nodded to my surprise, but added, ‘Then you have not been here since the Red Ship War ended. All this has sprung up in the last ten years or so. When trade improved, more folk wanted to live near Buckkeep, and yet did not want to be too far from the castle lest the raids resume.’

I could think of no sensible reply to her words, but the new stretch of town still surprised me. There was even a tavern as we got closer to the docks, and a hiring hall for rivermen. We rode past a row of warehouses that fronted onto the docks. Donkey-carts seemed the favoured transportation. Blunt-nosed river craft were tied up to the docks, unloading cargo from Farrow and Tilth. We passed another tavern, and then several cheap rooming-houses such as sailors seem to favour. The road followed the river upstream. Sometimes it was wide and sandy; in other places timbers had been laid in a sort of boardwalk over boggy stretches. The other horses seemed to take no notice of the change, but at every one we traversed, my black slowed her pace and set back her ears. She did not like the drumming of her hooves on the timber. I set my hand to her withers and quested towards her, offering reassurance. She turned her head to roll an eye at me, but remained as distant as ever. She probably would have refused to go on if there had not been two other horses to follow. She was plainly far more interested in her own kind than in any companionship I might offer.

I shook my head at the difference between her and the amiable horses in Burrich’s stable, and wondered if his Wit had made the difference. Whenever a mare birthed a foal, Burrich was at her side, and the baby knew the touch of his hand almost as soon as it knew the lick of its mother’s tongue. Was it merely the early presence of a human that had made the beasts in his stable so accepting, or was it his own Wit, suppressed but still present, that had made them so receptive to me?

The afternoon sun beat down on us, and the sun bounced off the river’s wide and gleaming surface. The thudding hooves of the three horses were a pleasant counterpoint to my thoughts as I pondered. Burrich had seen the Wit as a dark and low magic, a temptation to let the beast in my nature overwhelm me. Common lore agreed with him and went further; the Wit was a tool for evil, a shameful magic that led its practitioners into degradation and wickedness. Death and dismemberment was the only recognized cure for the Wit. My equanimity over Dutiful’s absence was suddenly threatened. True, the boy had not been kidnapped. But although the Skill had let me find him, it was undoubtedly the Wit the boy was employing in his night hunts. If he betrayed himself to anyone, he might be put to death. Perhaps not even his status as a prince would be enough to protect him from that fate. After all, the Wit had been enough to tumble me from the favour of the Coastal Dukes straight into Regal’s dungeons.

No wonder Burrich had given up all use of the Wit. No wonder he had so often threatened to beat it out of me. Yet I could not regret having it. Curse or blessing, it had saved my life more often than it had endangered it. And I could not help but believe that my deep sense of kinship with all life enhanced my days. I drew a deep breath and cautiously let my Wit unfold into a general sensing of the day around me. My awareness of both Malta and the Huntswoman’s horse sharpened, as did their acknowledgement of me. I sensed Laurel, not as another rider beside me, but as a large and healthy creature. Lord Golden was as unknowable to my Wit as the Fool ever was. From even that sense, he rippled aside, and yet his very mystery was a familiar one to me. Birds in the trees overhead were bright startles of life amongst the leaves. From the largest of the trees we passed, I sensed a deep green flow of being, a welling of existence that was unlike an animal’s awareness and yet was life all the same. It was as if my sense of touch expanded beyond my skin to make contact with all other forms of life around me. All the world shimmered with life, and I was a part of that network. Regret this oneness? Deny this expanded tactility?

‘You’re a quiet one,’ Laurel observed. With a start I became aware of her as a person again. My thoughts had run so deep, I had almost forgotten the woman riding beside me. She was smiling at me. Her eyes were pale blue, but with rings of darker blue at the edges. One iris, I noted, had an odd streak of green in it, radiating out from the centre. I could think of no reply so I simply shrugged and nodded. Her smile grew wider.

‘Have you been Huntswoman for the Queen long?’ I asked, simply to be saying something.

Laurel’s eyes grew thoughtful as she totted up the years. ‘Seven years now,’ she said quietly.

‘Ah. Then you know her well,’ I rejoined, wondering how much she truly knew of our present errand.

‘Well enough,’ Laurel replied, and I could almost see her wondering the same about me.

I cleared my throat. ‘Lord Golden visits Galeton in search of gamebirds. He has a passion for collecting feathers, you know.’ I did not directly ask any question.

She looked at me from the corner of her eye. ‘Lord Golden has many passions, it is said,’ she observed in a low voice. ‘And the funds to indulge them all.’ She gave me another glance, as if to ask if I would defend my master, but if there was an insult, I did not take its meaning. She looked ahead and spoke on. ‘As for me, I but travel along to scout the hunting for my queen. She likes to go after gamebirds in the autumn. I have hopes that in Galeton woods we may find the kind that she likes best.’

‘So do we all hope,’ I agreed. I liked her caution. We would get along well enough, I decided.

‘Have you known Lord Golden long?’ she asked me.

‘Not directly,’ I hedged. ‘I had heard he was looking for a man, and I was glad when an acquaintance recommended me.’

‘Then you’ve done this kind of work before?’

‘Not for some time. For the past ten years or so I’ve lived quietly, just my boy and me. But he’s of an age to apprentice out, and that takes hard coin. This is the fastest way I know to earn it.’

‘And his mother?’ she asked lightly. ‘Won’t she be lonely with both of you away?’

‘She’s gone many years,’ I said. Then, realizing that Hap might sometime venture up to Buckkeep, I decided to keep as close to the truth as I could. ‘He’s a fosterling I took in. I never knew his mother. But I think of him as my son.’

‘You’re not married, then?’

The question surprised me. ‘No, I’m not.’

‘Neither am I.’ She gave me a small smile as if to say this gave us much in common. ‘So, how do you like Buckkeep so far?’

‘Well enough. I lived close by when I was a boy. It’s changed a great deal since then.’

‘I’m from Tilth myself. Up on the Branedee Downs is where I grew up, though my mother was from Buck. Her family lived not far from Galeton; I know the area, for I ranged there as a child. But mostly we lived near the Downs, where my father was Huntsman for Lord Sitswell. My father taught both my brothers and me the skills of being a huntsman. When he died, my older brother took his position. My younger brother returned to live amongst my mother’s people. I stayed on, mostly training the coursing horses in Lord Sitswell’s stable. But when the Queen and her party came hunting there years ago, I turned out to help, for the party was so large. The Queen took a liking to me, and –’ she grinned proudly ‘– I’ve been her Huntswoman ever since.’

I was trying to think of something more to say when Lord Golden beckoned us both to come closer.

I urged the black forwards and when we were close, he announced, ‘Those were the last of the houses for a way. I did not want folks saying that we rode in great haste, but neither do I wish to miss this evening’s only ferry from Lampcross. So now, good people, we ride. And, Badgerlock, we’ll see if that black is truly as fleet as the horse-seller said. Keep up as best you can. I’ll hold the ferry for us all.’ So saying, he touched his heels to Malta and let out her reins. It was all the permission she required. She sprang forwards, showing us her heels.

‘My Whitecap can match her any day!’ Laurel proclaimed, and gave her horse her head.

Catch them! I suggested to the black, and was almost shocked at her competitive response. From a walk, she all but leapt into a run. The smaller horses had the lead on us. Packed mud flew up from their hooves, and Malta led only by virtue of the narrowing trail. My black’s longer stride diminished their lead until we were close behind them, getting the full benefit of the mud they threw. The sound of us behind them spurred them to greater effort and once more they pulled ahead of us. But I could feel that my black had not yet hit her peak. There was still unrealized reach in her stride, and the tempo of her gait said that she had not reached her hardest gallop. I tried to hold her back where the flying clods would not shower us so heartily, but she paid no heed to the rein. The moment the trail widened, she surged forwards into the gap, and in a few strides she passed them both. I heard them both cry out to their horses, and I thought they would overtake us. But like a lengthening wolfhound on the scent, my black reached out to seize even longer strides of the path and fling it behind us. I glanced back at them once, to see both their faces alight with the challenge.

Faster, I suggested to my black. I did not really think she had more speed in her, but as a flame roars up a dry tree, she surged forwards again. I laughed aloud at the pure joy of it, and saw her ears flicker in response. She did not reach towards my mind with any thought, but I felt a tentative glimmer of her approval. We would do well enough together.

We were first to reach Lampcross Ferry.

FIFTEEN Galeton

Since the time of the Piebald Prince, the scouring of the Witted has been accepted within the Six Duchies as matter-of-factly as enforced labour for bad debt or flogging for thieves. It was the normal way of the world, and unquestioned. In the years following the Red Ship War, it was natural that the purging should begin in earnest. The Cleansing of Buck had freed the land of the Red Ship Raiders and the Forged ones they had created. Honest folk hoped to purify the Six Duchies of unnatural taints completely. Some were, perhaps, too swift to punish on little evidence. For a time, accusations of being Witted were enough to make any man, guilty or not, tremble for fear of his life.

The self-styled Piebalds took advantage of this climate of suspicion and violence. While not revealing themselves, they publicly exposed well-known figures who were possessed of the Wit but never spoke out against the persecution of their more vulnerable fellows. It was the first attempt by the Witted as a group to wield any sort of political power. Yet it was not the effort of a people to defend themselves against unjust persecution, but the underhanded tactic of a duplicitous faction determined to seize power for themselves by any available means. They had no more loyalty to themselves than a pack of dogs.

Delvin’s The Politics of the Piebald Cabal

As it turned out, my race to the ferry landing was of small use. The ferry was there and tied up, and so it would remain, the captain told me, until an expected cargo of two waggons of sea salt arrived. When Lord Golden and Laurel arrived, which, to speak fairly, was not so much longer after I did, the captain remained adamant. Lord Golden offered him a substantial purse to leave without the waggons, but the captain shook his head with a smile. ‘I’d have your coins once, and nice as they might clink, I could only spend them once. I wait for the waggons at Lady Bresinga’s request. Her coins come to me every week, and I’ll not do anything to risk her ill-will. You’ll have to wait, good sir, begging your pardon.’

Lord Golden was little pleased with this, but there was nothing he could do. He told me to remain there with the horses, and took himself off to the landing inn where he could have a mug of ale in comfort while he waited. It was in keeping with our roles, and I harboured no resentment. I told myself this several times. If Laurel had not been with us, perhaps he would have found a way for us to share some time without compromising our public roles. I had looked forwards to a companionable journey with him and time in which we did not have to maintain our façade of master and servant but I resigned myself to what was necessary. Still, something of my regrets must have showed in my face, for Laurel came to keep pace with me as I walked the horses about in a field near the ferry landing. ‘Is something troubling you?’ she asked me.

I glanced at her in some surprise at the sympathy in her voice. ‘Just missing an old friend,’ I replied honestly.

‘I see,’ she answered, and when I offered no more on the topic, she observed, ‘You’ve a good master. He held no grudge against you that you beat him in our race. Many’s the master who would have found a way to make you regret your victory over him.’

The idea startled me, not as Tom Badgerlock but as Fitz. It had never occurred to me that the Fool might resent a race fairly won. Plainly I was not fully settled into my role. ‘That’s true, I suppose. But the victory was his as much as mine. He chose the horse, and at first I was not much impressed with the beast. But she can run, and in running she showed a spirit I didn’t suspect she had. I think I can make a good mount of her yet.’

Laurel stepped back to run a critical eye over my black. ‘She seems a good mount to me. What made you doubt her?’

‘Oh.’ I searched for words that would not make me sound Witted. ‘She seemed to lack a certain willingness. Some horses want to please. Your Whitecap is one, and Malta another. My black seems to lack that. But as we get to know one another, perhaps it will come.’

‘Myblack? That’s her name?’

I shrugged and smiled. ‘I suppose so. I hadn’t given her one, but, yes, I suppose that’s what I’ve been calling her.’

She gave me a sideways glance. ‘Well, it’s a little better than Blacky or Queenie.’

I grinned at her disapproval. ‘I know what you mean. Well, she may yet show me a name that fits her more truly, but for now she’s Myblack.’

For a time we walked in silence. She kept glancing up the roads that led down to the ferry landing. ‘I wish those waggons would come. I don’t even see them.’

‘Well, the land rises and falls a good deal along here. They may crest a hill anytime and come into view for us.’

‘I hope so. I’d like to be on our way. I’d hoped to reach Galeton before full dark. I’d like to get up in the hills as soon as possible and take a look around.’

‘For the Queen’s quarry,’ I supplied.

‘Yes.’ She glanced aside from me for a time. Then, as if making sure I understood that she did not break a confidence, she said bluntly, ‘Queen Kettricken told me that both you and Lord Golden are to be trusted. That I need hold nothing back from either of you.’

I bowed my head to that. ‘The Queen’s confidence honours me.’

‘Why?’

‘Why?’ I was startled. ‘Well, such confidence from such a great lady to one like me is –’

‘Unbelievable. Especially when you arrived in Buckkeep Castle but a few days ago.’ Her eyes met mine squarely.

Kettricken had chosen her confidante well. Yet her very intelligence could be a threat to me. I licked my lips, debating my answer. A small piece of truth, I decided. Truth was easiest to keep straight in later conversations. ‘I have known Queen Kettricken of old. I served her in several confidential ways during the time of the Red Ship war.’

‘Then it was for her that you came to Buckkeep rather than Lord Golden?’

‘I think it is fair to say I came for myself.’

There was a time of silence. Together we led our horses to the river and allowed them to drink. Myblack showed no caution of the water, wading out to drink deep. I wondered how she would react to boarding the ferry. She was big and the river was wide. If she decided to give trouble, it could be an unpleasant crossing for me. I dipped a kerchief in the cold water and wiped my face with it.

‘Do you think the Prince just ran away?’

I dropped the kerchief from my eyes to stare at her in surprise. This woman was blunt. She did not look away from me. I glanced about to be sure no one could hear us. ‘I don’t know,’ I said as bluntly. ‘I suspect he may have been lured rather than taken by force. But I do think others were involved in his leaving.’ Then I bit my tongue and chided myself for being too open. How would I back up that opinion? By revealing I was Witted? Better to listen than to talk.

‘Then we may be opposed in recovering him.’

‘It’s possible.’

‘Why do you think they lured him away?’

‘Oh, I don’t know.’ I was beginning to sound vapid and I knew it.

She met my eyes squarely. ‘Well, I also think he was lured away, if not taken outright. I speculate that those who took him did not approve of the Queen’s plan for marrying him to the Outislander narcheska.’ She glanced away and added, ‘Nor do I.’

Those words gave me pause. It was the first hint that she was not unquestioning in her loyalty to the Queen. All Chade’s old training came to the fore, as I sought to see how deep her disagreement ran. Could she have had something to do with the Prince’s disappearance? ‘I am not sure that I agree with it myself,’ I replied, inviting her to say more.

‘The Prince is too young to be pledged to anyone,’ Laurel said forthrightly. ‘I have no confidence that the Out Islands are our best allies, let alone that they will remain true. How can they? They are little more than city-states scattered along the coast of a forbidding land. No one lord holds true power there, and they squabble constantly. Any alliance we make there is as like to draw us into one of their petty wars as to benefit us in trade.’

I was taken aback. She had obviously given this a great deal of thought, and in a depth I would not have expected of a huntswoman. ‘What would you favour, then?’

‘Were the decision mine – and well I know it is not – I would hold him back, in reserve as it were, until I saw surely what was happening, not just in the Out Islands but to the south as well, in Chalced and Bingtown and the lands beyond. There has been talk of war down there, and other wild tales. Dragons have been seen, they do say. Not that I believe all I hear, but dragons did come to the Six Duchies during the Red Ship War. I’ve heard those tales too often to set them aside. Perhaps they are attracted to war and the prey it offers them.’

To enlighten her in that regard would have required hours. I merely asked, ‘Then you would marry our prince off to a Chalcedean noblewoman, or a Bingtown Trader’s daughter?’

‘Perhaps it would be best for him to marry within the Six Duchies. There are some who mutter that the Queen is foreign-born, and that a second generation of a foreign queen might not be good.’

‘And you agree?’

She gave me a look. ‘Do you forget I am the Queen’s Huntswoman? Better a foreigner like her than some of the Farrow noblewomen I’ve had to serve in the past.’

Our talk died there for a time. We led the horses away from the river. I removed bits and let the animals graze. I was hungry myself. As if she could read my thoughts, Laurel dug into her saddlebag and came up with apples for us both. ‘I always carry food with me,’ she said as she offered it to me. ‘Some of the folk I’ve hunted for think no more of the comfort of their hunters than they do of their horses or dogs.’

I bit back a response that would have defended Lord Golden from such a charge. Best to let the Fool decide how he wished to present himself. I thanked her and bit into the apple. It was both tart and sweet. Myblack lifted her head suddenly.

Share? I offered her.

She flicked her ears at me disdainfully and went back to grazing.

A few days without me and he’s consorting with horses. I might have known. The wolf used the Wit without subtlety, startling me and spooking all three horses. ‘Nighteyes!’ I exclaimed in surprise. I looked around for him.

‘Beg pardon?’

‘My … dog. He’s followed me from home.’

Laurel looked at me as if I were mad. ‘Your dog? Where?’

Luckily for me, the great wolf had just come into view, slipping out of the shelter of the trees. He was panting, and he headed straight for the river to drink. Laurel stared. ‘That’s a wolf.’

‘He does look a great deal like a wolf,’ I conceded. I clapped my hands and whistled. ‘Here, Nighteyes. Here, boy.’

I’m drinking, you idiot. I’m thirsty. As you might be if you had trotted all the way here instead of riding a horse.

‘No,’ Laurel replied evenly. ‘That is not a dog that looks like a wolf. That is a wolf.’

‘I adopted him when he was very small.’ Nighteyes was still lapping. ‘He’s been a very good companion to me.’

‘Lady Bresinga may not welcome a wolf into her home.’

Nighteyes lifted his head suddenly, looked about, and then without a glance at me, slunk back into the woods. Tonight. He promised me in parting.

I’ll be on the other side of the river by tonight.

So will I. Trust me. Tonight.

Myblack had caught Nighteyes’ scent and was staring after him. She whickered uneasily. I looked back at Laurel and found her regarding me curiously.

‘I must have been mistaken. That was, indeed, a wolf. Looked a great deal like my dog, though.’

You’ve made me look like an idiot.

That wasn’t hard.

‘It was a very peculiar way for a wolf to behave,’ Laurel observed. She was still staring after him. ‘It’s been years since I’ve seen a wolf in these parts.’

I offered Myblack the apple core. She accepted it, and left a coating of green slime on my palm in return. Silence seemed the wisest choice.

‘Badgerlock! Huntswoman!’ Lord Golden summoned us from the roadside. In great relief, I led the horses over to him.

Laurel trailed us. As we approached him across the meadow, she made a small sound of approval in her throat. I glanced back at her in consternation. Her eyes were fixed on Lord Golden, but at my questioning glance, she quirked a small smile at me. I looked back at him.

Aware of our scrutiny, he all but struck a pose. I knew the Fool too well to be fooled by Lord Golden’s careless artifice. He knew how the wind off the river toyed with his golden locks. He had chosen his colours well, blues and white, and his elegant clothing was cut to complement his slender figure. He looked like a creature of sun and sky. Even carrying food bundled in a white linen napkin and a jug, he still managed to look elegantly aristocratic.

‘I’ve brought you a meal and drink so you’ll not be tempted to leave the horses untended,’ he told me. He handed me the napkin and the moisture beaded jug. Then he ran his eyes over Laurel and gave her an approving smile. ‘If the Huntswoman would enjoy it, I would be pleased to share a meal with her while we await those cursed waggons.’

The fleeting glance Laurel sent my way was laden with meaning. She begged my pardon for deserting me even as she was certain I could see this was too rare an opportunity for her to miss it.

‘I am certain I would enjoy it, Lord Golden,’ she replied, inclining her head. I took Whitecap’s reins before she could think to ask me. Lord Golden offered her his arm as if she were a lady. With only the slightest hesitation, she set her sun-browned fingers on the pale blue of his sleeve. He immediately covered her hand with his long, elegant fingers. Before they were three steps away from me, they were in deep conversation about game birds and seasons and feathers.

I closed my mouth, which had been hanging just slightly ajar. Reality re-ordered itself around me. Lord Golden, I suddenly realized, was every bit as complete and real a person as the Fool had been. The Fool had been a colourless little freak, jeering and sharp-tongued, who tended either to rouse unquestioning affection or abhorrence and fear in those who knew him. I had been among those who had befriended King Shrewd’s jester, and had valued his friendship as the truest bond two boys could share. Those who had feared his wickedly-barbed jests and been repulsed by his pallid skin and colourless eyes had been the vast majority of the castle folk. But just now an intelligent and I must admit, very attractive young woman had just chosen Lord Golden’s companionship over mine.