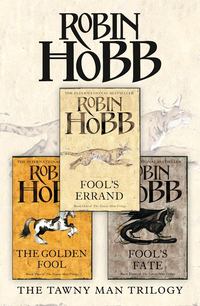

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

The depths of the night had passed and we were venturing towards the shallows of dawn when there was a tap at the door. A dour-faced maid informed me that my master required my assistance. Heart in mouth, I followed her, to discover Lord Golden senseless with drink on a bench in a parlour. He sprawled there like a cast-off garment. If other folk had witnessed his collapse, they had left. Even the maid gave a small toss of her head as she abandoned me to tend to him. As soon as she left, I half-expected him to rouse and tip me a wink that this was all a sham. He did not.

I hauled him to his feet but even that did not stir him. I could either drag him or carry him. I resorted to the undignified expediency of slinging him over my shoulder and toting him back to his chamber like a sack of grain. I dumped him unceremoniously onto the bed, and fastened the door behind us. Then I dragged off his boots and shook him out of his jacket. As he fell back onto the bed, he said, ‘Well, I did it. I’m certain of it. I’ll apologize tomorrow, most abjectly, to Lady Bresinga. Then we’ll leave immediately. And all will be relieved to see us go. No one will follow us, no one will suspect we track the Prince.’ His voice wavered towards the end of this speech. He still had not opened his eyes. Then, in a strained voice he added, ‘I think I’m going to vomit.’

I brought him the washbasin and set it on the bed next to him. He crooked an arm around it as if it were a doll. ‘What, exactly, did you do?’ I demanded.

‘Oh, Eda, make it all stand still.’ He clenched his eyes tightly and spoke. ‘I kissed him. I knew that would do it.’

‘You kissed Sydel? Civil’s intended?’

‘No,’ he groaned, and I knew a short-lived moment of relief. ‘I kissed Civil.’

‘What?’

‘I had gone to piss. When I came back, he was waiting for me outside the parlour where the others were gaming. He grabbed my arm and all but dragged me into a sitting room where he confronted me. What were my intentions towards Sydel? Did not I grasp that they had an understanding?’

‘What did you say?’

‘I said–’ He paused abruptly and his eyes grew round. He leaned towards the basin, but after a moment he only burped gassily and lay back. He groaned, then continued: ‘I said I understood their understanding, and hoped that perhaps we could come to an understanding of our own. I clasped his hand in mine. I said I saw no difficulty. That Sydel was a lovely girl, as lovely a girl as he was a boy, and that I hoped we might all become close and loving friends.’

‘And then you kissed him?’ I was incredulous.

Lord Golden screwed his eyes shut. ‘He seemed a bit naïve. I wanted to be sure he took the fullness of my meaning.’

‘Eda and El in a tangle,’ I swore. I stood up and he groaned as the bed moved beneath him. I walked to the window and stared out. ‘How could you?’ I demanded of him.

He took a breath and strained mockery crept into his voice. ‘Oh, please, beloved. You needn’t be jealous. It was the most brief and chaste kiss you can imagine.’

‘Oh, Fool,’ I rebuked him. How could he make a jest of something like this?

‘It wasn’t even on the mouth. Just a warm press of my lips to the palm of his hand, a single flick of my tongue.’ He smiled feebly. ‘He snatched it away as if I had branded him.’ Suddenly he hiccuped loudly and then made a sour face. ‘You’re dismissed. To your room, Badgerlock. I’ve no more need of you tonight.’

‘Are you certain?’

He nodded, a short vehement nod. ‘Go away,’ he said plainly. ‘If I’m going to puke, I don’t want you watching me.’

I understood his need to preserve that much dignity. He had little enough left. I retreated to my room and shut the door. I busied myself with packing my things. A short time later, when I heard the sounds of his misery, I did not go to him. Some things a man should do alone.

I did not sleep well. I longed to touch minds with my wolf, but dared not allow myself that comfort. Necessary they might be, yet I still felt dirtied by the Fool’s political manipulations. I longed to live the direct and clean life of a wolf. Towards dawn, I came out of a doze to the sound of the Fool moving about in his chamber. I found him sitting at the small table looking haggard. Somehow the fresh clothing he had donned only made him look the more rumpled. Even his hair looked sweaty and dishevelled. He had a little box in front of him and a mirror. As I watched, puzzled, he dipped his finger in something and wiped it under his eye. The shadow there deepened to a pouch. Then he sighed. ‘I hate what I did last night.’

I did not need him to explain. I tried to ease his conscience. ‘Perhaps it was a kindness. Perhaps it is better they discovered, before they wed, that Sydel’s heart is not as constant as Civil believed.’

He shook his head, refusing the comfort. ‘If I had not led, she would not have followed in that dance. Her first sallies were but a girl’s coquetry. I think it as instinctive for a girl to flirt as it is for boys to show off their muscles and daring. Girls of her age are like little kittens pouncing at grass to practise their hunting skills. They do not yet know the meaning of the motions they make.’ He sighed, and went back to his little box of coloured powders.

Silently I watched as he not only made himself look more ill, but added a decade to his years by delineating the lines in his face.

‘Do you think that’s necessary?’ I asked him as he snapped the little box shut and handed it to me. I tucked it back into his case, which was, I noted, already neatly packed for our journey.

‘I do. I wish to be sure that the glamour I put over Sydel is completely broken before I depart. Let her see me as substantially older than she is, and dissolute. She will wonder what she was thinking, and flee back to Civil. I hope he will have her. It would be better than her pining after me.’ He gave a melodramatic sigh, but I knew his ridicule was for himself. This morning, Lord Golden’s façade was fractured and the Fool shone forth from the cracks.

‘A glamour?’ I asked sceptically.

‘Of course. No one is invulnerable to me if I choose to enchant them. No one but you, that is.’ He rolled his eyes at me dolorously. ‘But there is no time for me to mourn that. Now you must go forth and make it known that I wish a private moment with Lady Bresinga. Then go and tap at Laurel’s door and let her know that we ride soon.’

By the time I returned from the second half of my errand, Lord Golden had departed the room to his meeting with Lady Bresinga. It was a very brief meeting, and when he returned, he indicated that I should take our bags down immediately. He did not stop to eat anything, but I had already purloined all the fruit that had been in our room. We would survive, and he was probably wiser to avoid food for a time yet.

Our horses were brought round. Lady Bresinga descended to wish us a chill farewell. Not even the servants deigned to notice our departure. Lord Golden offered yet another apology, attributing much of his behaviour to the fine quality of her wines. If this flattery was meant to appease her, it failed. We rode slowly from her courtyard, Lord Golden setting a very easy pace for us. At the foot of the hill, we turned towards the ferry. Only when the line of trees along the road hid us from the manor’s view did he halt and ask me, ‘Which way?’

Laurel had been riding in a mortified silence. She had said nothing, but I gathered that in humiliating himself, Lord Golden had daubed her with the same brush. Now she looked shocked as I said, ‘This way,’ and turned Myblack off the road and into the sun dappled forest.

‘Don’t wait for us,’ he told me brusquely. ‘Go as swiftly as you can to close the gap. We’ll catch up as we may, though my poor head may hold us back a bit. The worry now is that we may lose his trail. I am certain Laurel can follow yours. Go now.’

I wanted no more than that. I saw the purpose of his order at once. It would allow me to be alone when I overtook Nighteyes and to confer with him privately. I nodded once and set my heels to Myblack. She sprang forwards willingly, and I let my heart lead us. I did not bother looping back to where I had last seen the wolf, but reined her north and east to where I knew he was today. I let a tiny thread of my awareness tug at him to let him know I was coming and felt the twitch of his response. I urged Myblack to greater speed.

Nighteyes had covered a surprising amount of ground. I did not let myself worry about whether or not Laurel could track me easily. My drive now was to rejoin my wolf, see that he was well, and then to push on in pursuit of the Prince. My uneasiness for him had been steadily swelling.

The day was hot, summer’s last sprawl across the land, and the sun beat down on us even through the thin shade of the trees. The dry air seemed laden with dust that sucked the moisture from my mouth and clung to my eyelashes. I did not bother trying to find trails but pushed Myblack through the forested hills and down into the dales between them. Lusher vegetation showed where creeks sometimes ran, but their waters seeped under the surface now. Twice we crossed streams, and each time I stopped to let Myblack water and to drink deeply myself. Then we pushed on.

By early afternoon, I had an indefinable conviction that Nighteyes was near. Before I saw him or scented him, I began to get the strange feeling that I had seen this terrain before, that something about those trees ahead was oddly familiar. I pulled in the horse and slowly scanned the hills around me, only to have him step out from a patch of alder brush scarce a stone’s throw away. Myblack flinched and then focused her full attention on him. I set a hand to her neck. Calm. No need to fear. Calm.

Too tired and not hungry enough to chase you, Nighteyes added helpfully.

‘I brought you meat.’

I know. I smell it.

I had scarcely unwrapped it before it was gone. I wanted to look at his injuries, but knew better than to bother him with that while he was eating. And as soon as he had finished eating, he gave himself a shake. Let’s go.

Let me look at …

No. Maybe tonight. But while they have light, they travel, and so must we. They already have a good start on us, and the dry soil holds their scents poorly. Let’s go.

He was right about tracking them. The dry ground resisted both print and scent. Before the afternoon was over, we had twice been stymied, and had only rediscovered their trail by casting for it in a wide circle. The shadows were growing long when Lord Golden and Laurel caught up with us. ‘I see your dog has found us again,’ she observed wryly, and I could think of nothing to say in reply.

‘Lord Golden tells me that you track the Prince, that a serving girl told you the Prince had fled north?’ There was question in her voice, and her mouth was flat with disapproval. I did not know if she hoped to catch Lord Golden in a lie, or if I was supposed to have seduced someone for the information.

‘She didn’t know he was the Prince. She simply called him a lad with a hunting cat.’ I tried to think of something that would divert her from more questions. ‘The trail is poor. Any help you could give me would be welcome.’

My ruse worked. She proved an able tracker. As the light went out of the day, she picked up small signs that I might have missed, and thus we kept following them long past the hour when I would have said the light was too poor. We came to a creek where they had stopped to water. The spoor of two men, two horses and the cat were all plain in the damp soil at the water’s edge. There we decided to make camp for the night. ‘It’s better to stop tracking while we know we are on the right trail than to wait until we are not certain, and have confused things with our own tracks. Early tomorrow we will start again,’ Laurel announced.

We made a bare camp, little more than a tiny fire and our blankets beside it. Food was in short supply, but at least we had plenty of water. The fruit I had taken from our room was warm and bruised but welcome. Laurel carried, from habit, some twists of dried meat and travel bread. There was precious little of it, and she unwittingly bought much good favour from me when she announced, ‘We don’t need the meat as much as the dog does. We have both fruit and bread.’ Another woman, I thought, might have ignored the wolf’s hunger and hoarded the meat for the next day. Nighteyes, for his part, deigned to take it from her hand. And afterwards, when I insisted on looking at his scratches, he did not snarl when she joined me, though she was wise enough not to attempt to touch him. As I had suspected, he had licked most of the unguent away. The scratches were scabbed closed and the flesh beside them did not look too angry. I decided against putting more ointment on them. As I put the unused pot away, Laurel nodded her head in quiet agreement. ‘Better dry and closed than greased too well and the scab softened too much.’

Lord Golden had already stretched out on his blanket. I surmised that neither his head nor his belly were yet calm. He had spoken little throughout our camp-making and sparse meal. In the gathering dark, I could not tell if his eyes were closed or if he stared up at the sky.

‘Well, I suppose he has the right of it,’ I said, gesturing at him. ‘Early to bed, and an early start tomorrow. Perhaps, with luck, we’ll overtake them.’

I think Laurel assumed Lord Golden was already asleep. She lowered her voice. ‘It will take some hard riding, as well as a measure of luck. They ride assuredly, knowing where they are bound, while we must go carefully lest we lose them.’ Laurel cocked her head and studied me across the small fire. ‘How did you know when to leave the road to find their trail?’

I took a breath and chose a lie at random. ‘Luck,’ I replied quietly. ‘I had a feeling they would be going in this direction, and when I struck their trail, we followed it.’

‘And your dog had the same feeling, which is why he had gone ahead of you?’

I just looked at her. The words rose to my tongue without my volition. ‘Maybe I’m Witted.’

‘Oh, yes,’ she replied sarcastically. ‘And that is why the Queen trusts you to go after her son. Because you are one of those she most fears. You are not Witted, Tom Badgerlock. I’ve known Witted folk before; I’ve endured their disdain and snubs for folks who do not share their magic. Where I grew up, there were plenty of them, and in that place and time, they did little to conceal it. You are no more Witted than I am, though you are one of the best trackers I’ve ever ridden with.’

I did not thank her for the compliment. ‘Tell me about the Witted folk you grew up with,’ I suggested. I smoothed a wrinkle out of my blanket and lay back on top of it. I closed my eyes almost all the way, as if I were only mildly interested in her words. The moon, a paring less than full, looked down at us through the trees. At the edge of the fire’s light, Nighteyes was diligently licking himself. Laurel fussed for a moment with her own blanket, tossing small stones out from under it. Then she smoothed it to the earth and lay back on it. She was silent for a moment or two and I did not think she was going to answer me.

Then, ‘Oh, they were not so bad. Not like the tales folk tell. They did not turn into bears or deer or seals at the light of the full moon, nor did they eat raw meat and steal children. Still, they were bad enough.’

‘How?’

‘Oh,’ she hesitated. ‘It just was not fair,’ she said at last, with a sigh. ‘Imagine never being sure that you were alone, for some little bird or lurking fox might carry the eyes and ears of your neighbour. They took full advantage of their Wit, for their animal partners forever told them where the hunting was best or the berries first ripened.’

‘Were they that open that they were Witted? Never have I heard of such a village.’

‘It was not that they were open about what they were, so much as that I was excluded for what I was not. Children are not subtle.’

The bitterness of her words shocked me. I recalled, abruptly, how the rest of Galen’s coterie had treated me with disdain when I could not seem to master the Skill. I tried to imagine growing up amidst such snubbing. Then a thought intruded. ‘I thought your father was Huntsman for Lord Sitswell. Did not you grow up on his estate, then?’ I wanted to know where this place was, where Witted ones were so common their children had come to expect it of their playmates.

‘Oh. Well, but that came later, you see.’

I was not sure if she lied then, or if she had lied earlier, only that the untruth hung almost palpably between us. It made an uncomfortable silence. My mind darted amongst the possibilities. That she was Witted, that she was an unWitted child in a family with Witted siblings or parents, that she had made the whole tale up, that all of Lord Sitswell’s manor was riddled with Witted servants. Perhaps Lord Sitswell himself was of the Old Blood. Such speculation was not entirely useless. It prepared the mind to sort whatever other information she might toss my way into the appropriate possibilities. I harked back to an earlier conversation we had had, and found a chance remark that put a chill down my back. She had said she would know these hills well, having spent time not far from Galeton, amongst her mother’s folk. Chade, too, had mentioned something of that. I tried to find a way to renew the conversation.

‘So. You sound as if you do not share the currently fashionable hatred of the Witted. That perhaps you do not wish to see them all burned and cut up.’

‘It’s a filthy habit,’ she said, and the way she said it made me feel as if fire and blade were too small a cure for it. ‘I think that parents who teach their children to indulge it should be whipped. Those that choose to practise it should not marry nor have children. They already have a beast to share their homes and lives. Why should they cheat a woman or a man by taking a spouse? Those who are Witted should have to choose, early in their lives, which they will bind to, an animal or another human. That’s all.’

Her voice had risen on the vehemence of her reply. At her last words, it dropped away, as if she suddenly recalled that Lord Golden was sleeping. ‘Good night, Tom Badgerlock,’ she added belatedly. She tried to soften her tone, perhaps, but it still plainly told me that our talk was over. As if to emphasize it, she rolled on her blanket to put her back to me.

Nighteyes rose with a groan and came stiffly to me. He lay down beside me with a sigh. I let my hand come to rest on his ruff. Our shared thoughts flowed as secretly as our blood.

She knows.

Then you think she is Witted? I asked him.

I think she knows that you are Witted, and I don’t think she likes it much.

For a time, I lay silently mulling that. But she fed you.

Oh, well, I think she likes me. It’s you she’s not sure about.

Go to sleep.

Are you going to reach after them tonight?

I didn’t want to. If I succeeded, it would give me a terrible headache. The mere thought of the pain made me nauseous. Yet if I could touch the Prince, I might gain information that could help us catch up sooner. I should try.

I felt his resignation. Go ahead, then. I’ll be right here.

Nighteyes. When I Skill and afterwards … do you share the pain?

Not exactly. Though it is hard for me to remain apart from it, I can. It just feels cowardly when I do.

It’s not cowardly at all. What is the point of both of us suffering?

He made no answer to me, but I sensed that he reserved some thought on that for himself. Something about my question almost amused him. I lifted my hand from his fur and set it on my chest. Then I closed my eyes, centred myself, and tried for a Skill-trance. Dread of pain kept intruding on my thoughts, pushing awry my carefully-constructed peace. Finally, I managed to find a balancing point and held myself there, somewhere between dreaming and waking. I reached forth into the night.

That night I felt, as I had not in years, the sweetness of the pure connection of the Skill. I reached out and it was as if someone reached back and clasped both my hands in welcome. It was a simple, sweet joining, as comforting as homecoming after a long journey. There was the linking of the Skill, and someone drowsing in a soft bed in a loft under the eaves of a thatched roof. The homely smells of a cottage surrounded me, the lingering smell of a good stew cooked that night, and the honey-tang of a beeswax candle burning late somewhere below. I could hear a man and a woman talking, their voices muted as if they did not want to disturb my rest. I could not make out their words, but I knew I was home and safe and that nothing could harm me there. As our Skill-link faded, I sank deeply into the most peaceful sleep I had known in many a year.

NINETEEN The Inn

During the years of the Red Ship War, when Prince Regal the Pretender wrongfully claimed to be King of the Six Duchies, he introduced a system of justice he called the King’s Circle. Trial by arms was not unknown in the Six Duchies. It is said that if two men fight before the Witness Stones, the gods themselves look down and reward victory to him whose cause is just. Regal took this idea one step further. In his arenas, accused criminals faced either his King’s Champions or wild beasts. Those who survived were judged to be innocent of the charges against them. Many Witted met their ends in those circles. Yet those who died in these bloody trials were but half of the evil done there. For what was born in those same contests was a public tolerance of violence and mayhem that swiftly became a hunger. These trials became spectacle and amusement as much as judgement. Although one of Kettricken’s first acts as queen and regent for young Dutiful was to put an end to such trials and have the Circles dismantled, no royal decision could quench the bloodlust that Regal’s spectacles had awakened.

I awoke very early the next morning with a sense of well-being and peace. An early morning fog was in the process of burning off. Dew glimmered on my blanket. For a time I gazed unthinking at the sky through the oak branches overhead. I was in a state of mind in which the black pattern against the blue was all that I needed to satisfy me. After a time, when my mind insisted on recognizing the sight before me as tree branches against the sky, I came back to myself and where I was and what I must do.

I had no headache. I could cheerfully have rolled over and slept most of the day away, but I could not decide if I was truly tired or simply wanted to return to the safety of my dreams. I forced myself to sit up.

Nighteyes was gone. The others still slept. I poked up the embers of the fire and fed it before it occurred to me that we had nothing to cook over it. We’d have to tighten our belts and follow the Prince and his companion. With luck, something edible would cross our path.

I drank from the stream and washed my face in the cool water. The day was already warming. As I was drinking, the wolf came back.

Meat? I asked hopefully.

A nest of mice. I didn’t save you any.

That’s all right. I wasn’t that hungry. Yet.

He lapped alongside me for a time, then lifted his muzzle. Where did you go, last night?

I knew what he meant. I’m not sure. But it felt safe.

It was nice. I’m glad you can get to a place like that.

There was wistfulness in his thought. I looked at him more closely. For an instant, I saw him as another might. He was an ageing wolf, grey on his muzzle, flesh sunken on his flanks. His recent encounter with the cat still hindered him. He ignored my concern to stare into the stream. Fish?

I let my annoyance seep into my thought. ‘Not a sign of one,’ I muttered aloud. ‘And there should be. Plenty of plants, midges buzzing. There should be fish here. But there aren’t.’

I felt his mental shrug at how life was. Wake the others. We need to get moving.