Английский детектив. Джон Бакен. Тридцать девять ступеней / John Buchan. The Thirty-Nine Steps

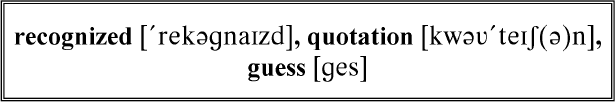

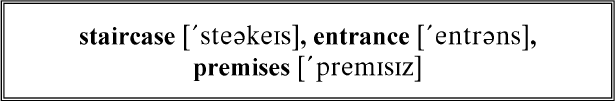

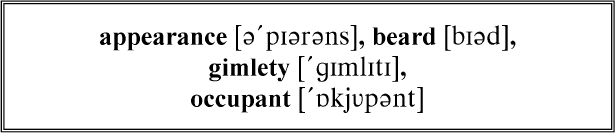

I was just fitting my key into the door (я как раз вставлял ключ в /замок/ двери) when I noticed a man at my elbow (когда заметил какого-то мужчину /совсем/ рядом: «у своего локтя»). I had not seen him approach (я не видел, как он подошел), and the sudden appearance made me start (и его внезапное появление заставило меня вздрогнуть). He was a slim man (это был худой мужчина), with a short brown beard and small, gimlety blue eyes (с короткой каштановой бородой и небольшими сверлящими голубыми глазами; brown – коричневый, бурый; /о цвете волос/ каштановый; gimlet – буравчик: eyes like gimlets – пронзительный или пытливый взгляд). I recognized him as the occupant of a flat on the top floor (я узнал в нем жильца квартиры на верхнем этаже), with whom I had passed the time of day on the stairs (с которым я здоровался: «обменивался временем дня» на лестнице).

‘Can I speak to you (могу я с вами поговорить)?’ he said. ‘May I come in for a minute (могу я зайти на минутку)?’ He was steadying his voice with an effort (он с трудом сдерживал голос; to steady – делать прочным, придавать устойчивость; успокаивать; steady – устойчивый; effort – усилие, попытка; напряжение), and his hand was pawing my arm (и его ладонь охватила мою руку; paw – лапа /животного/; лапища, ручища /о руке человека/; to paw – трогать лапой; хватать руками, лапать, шарить).

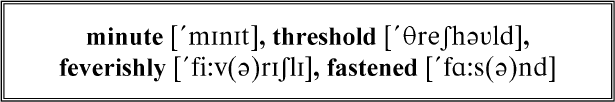

I got my door open and motioned him in (я открыл дверь: «сделал свою дверь открытой» и жестом пригласил его внутрь = войти; to get). No sooner was he over the threshold than he made a dash for my back room (как только он переступил порог, он бросился в дальнюю комнату: «сделал бросок в мою заднюю комнату»), where I used to smoke and write my letters (где я обычно курил и писал письма). Then he bolted back (после чего прибежал обратно; to bolt – запирать на засов; нестись стрелой, убегать; bolt – /арбалетная/ стрела).

‘Is the door locked (дверь заперта; lock – замок, запор; to lock – запирать на замок)?’ he asked feverishly, and he fastened the chain with his own hand (возбужденно спросил он и закрыл дверь на цепочку своей собственной рукой; fever – жар, лихорадка; нервное возбуждение; feverishly – лихорадочно; возбужденно; to fasten – связывать, скреплять; запирать).

I got my door open and motioned him in. No sooner was he over the threshold than he made a dash for my back room, where I used to smoke and write my letters. Then he bolted back.

‘Is the door locked?’ he asked feverishly, and he fastened the chain with his own hand.

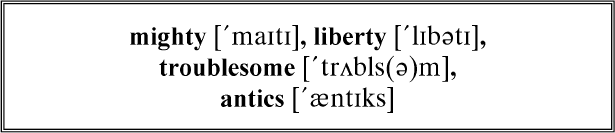

‘I’m very sorry (я очень сожалею),’ he said humbly (робко сказал он). ‘It’s a mighty liberty (это ужасная бесцеремонность; mighty – могущественный, мощный; /эмоц.-усил./ громадный; liberty – свобода; вольность, бесцеремонность), but you looked the kind of man who would understand (но у вас вид человека, который поймет; to look – смотреть, глядеть; выглядеть, иметь вид). I’ve had you in my mind all this week (я думал о вас: «имел вас в своем уме» всю эту неделю) when things got troublesome (когда /положение/ вещей стало затруднительным). Say, will you do me a good turn (послушайте, не окажете ли вы мне добрую услугу; turn – вращение, поворот; услуга)?’

‘I’ll listen to you (я вас выслушаю),’ I said. ‘That’s all I’ll promise (вот и все, что я пообещаю).’ I was getting worried by the antics of this nervous little chap (меня все больше тревожили гримасы: «я становился встревоженным гримасами» этого нервного малого; little – маленький, небольшой; невысокий, небольшого роста).

‘I’ll listen to you,’ I said. ‘That’s all I’ll promise.’ I was getting worried by the antics of this nervous little chap.

There was a tray of drinks on a table beside him (на столе рядом с ним стоял поднос с напитками), from which he filled himself a stiff whisky-and-soda (с которого он /взял стакан/ и наполнил /его/ крепким виски с содовой; stiff – жесткий, крепкий; крепкий /о напитках/). He drank it off in three gulps (он осушил: «выпил» его тремя большими глотками; to drink), and cracked the glass as he set it down (и расколол стакан, когда поставил его /обратно/; glass – стекло; стакан).

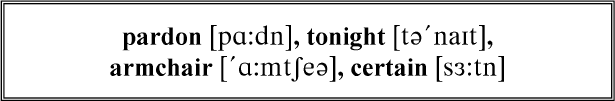

‘Pardon (извините),’ he said, ‘I’m a bit rattled tonight (я немного взволнован сегодня вечером; to rattle – трещать, грохотать; /разг./ взволновать, смутить, испугать). You see, I happen at this moment to be dead (видите ли, случилось так, что в этот момент я мертв).’

I sat down in an armchair and lit my pipe (я опустился в кресло и разжег трубку; to sit; to light).

‘What does it feel like (ну, и на что это похоже: «как это чувствуется»)?’ I asked (спросил я). I was pretty certain that I had to deal with a madman (я был совершенно уверен, что мне приходится иметь дело с сумасшедшим).

‘Pardon,’ he said, ‘I’m a bit rattled tonight. You see, I happen at this moment to be dead.’

I sat down in an armchair and lit my pipe.

‘What does it feel like?’ I asked. I was pretty certain that I had to deal with a madman.

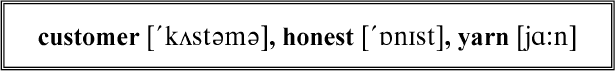

A smile flickered over his drawn face (улыбка промелькнула на его перекошенном лице; to flicker – мерцать; мелькнуть; drawn – искаженный, искривленный; to draw – тащить, тянуть). ‘I’m not mad – yet (я не сумасшедший – пока). Say, Sir, I’ve been watching you (послушайте, сэр, я наблюдал за вами), and I reckon you’re a cool customer (и я считаю, что вы человек хладнокровный; to reckon – считать, подсчитывать /особ. в уме/; полагать, придерживаться мнения; cool – прохладный, свежий; дерзкий, нахальный; customer – покупатель, заказчик; /разг./ тип, субъект). I reckon, too, you’re an honest man (я считаю, к тому же, что вы честный человек), and not afraid of playing a bold hand (и не боитесь играть смело: «смелой рукой»). I’m going to confide in you (я собираюсь довериться вам). I need help worse than any man ever needed it (я нуждаюсь в помощи больше, чем кто бы то ни было: «хуже, чем любой человек, который когда-либо нуждался в ней»), and I want to know if I can count you in (и я хочу знать, могу ли я привлечь вас; to count in – включить /в число, список и т. п./).’

‘Get on with your yarn (продолжайте свой рассказ; yarn – пряжа, нитки; /разг./ длинный рассказ о чем-л., история /особ. о приключениях/),’ I said, ‘and I’ll tell you (и я скажу вам).’

‘Get on with your yarn,’ I said, ‘and I’ll tell you.’

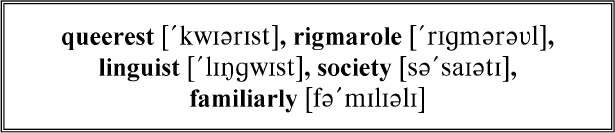

He seemed to brace himself for a great effort (он, казалось, собрал все силы для значительного напряжения; to brace – связывать, привязывать; напрячь силы, волю), and then started on the queerest rigmarole (и затем начал /нести/ наистраннейший вздор). I didn’t get hold of it at first (я не уловил смысл поначалу; to get hold – суметь схватить /часто мысль/), and I had to stop and ask him questions (и мне пришлось прерывать его и задавать ему вопросы). But here is the gist of it (вот в чем суть):

He was an American, from Kentucky (он был американцем из Кентукки), and after college, being pretty well off, he had started out to see the world (и после колледжа, будучи довольно хорошо обеспеченным, он отправился посмотреть мир). He wrote a bit, and acted as war correspondent for a Chicago paper (он немного писал и выступал в роли военного корреспондента для одной чикагской газеты; to write; to act – действовать, поступать; работать, действовать в качестве), and spent a year or two in South-Eastern Europe (и провел год или два в Юго-Восточной Европе; to spend). I gathered that he was a fine linguist (я понял /из его рассказа/, что он был прекрасным знатоком языков: «лингвистом»; to gather – собирать; делать вывод, умозаключение /на основании чего-л./), and had got to know pretty well the society in those parts (и что он узнал довольно хорошо общество в тех краях). He spoke familiarly of many names that I remembered to have seen in the newspapers (он свободно говорил о многих именах, которые, как я помню, я видел в газетах; to speak; familiarly – бесцеремонно, фамильярно; обычно, привычно).

He was an American, from Kentucky, and after college, being pretty well off, he had started out to see the world. He wrote a bit, and acted as war correspondent for a Chicago paper, and spent a year or two in South-Eastern Europe. I gathered that he was a fine linguist, and had got to know pretty well the society in those parts. He spoke familiarly of many names that I remembered to have seen in the newspapers.

He had played about with politics, he told me, at first for the interest of them (он занимался политической игрой, сказал он мне, поначалу из интереса к ней; politics – политика; политические махинации, интриги), and then because he couldn’t help himself (а затем – потому что уже не мог остановиться; cannot help oneself – быть не в состоянии /удержаться от чего-л./). I read him as a sharp, restless fellow (я определил его как умного, беспокойного малого; to read – читать; толковать, интерпретировать; sharp – острый, отточенный; умный, сообразительный), who always wanted to get down to the roots of things (которому всегда хотелось добраться до сути вещей; root – корень; база, основа). He got a little further down than he wanted (он зашел немного дальше, чем он сам того хотел).

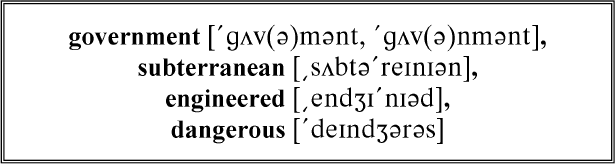

I am giving you what he told me as well as I could make it out (я сообщаю: «даю» вам то, что он рассказал мне, так, как я /сам/ смог разобрать). Away behind all the Governments and the armies there was a big subterranean movement going on (далеко позади всех правительств и армий разворачивалось большое тайное движение; subterranean – подземный; секретный, тайный, скрытый; to go on – продолжать путь; продолжаться, развиваться /о действии, процессе, состоянии/), engineered by very dangerous people (организованное очень опасными людьми; to engineer – создавать, сооружать; подстраивать, организовывать /путем происков, махинаций/).

I am giving you what he told me as well as I could make it out. Away behind all the Governments and the armies there was a big subterranean movement going on, engineered by very dangerous people.

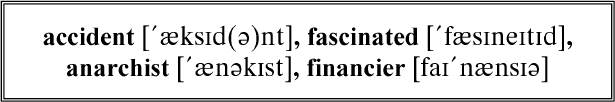

He had come on it by accident (он вышел на него случайно: «по случаю»; accident – несчастный случай, катастрофа; случай, случайность); it fascinated him (оно увлекло его); he went further, and then he got caught (он пошел дальше, а затем попался; to catch). I gathered that most of the people in it were the sort of educated anarchists that make revolutions (я пришел к выводу, что большинство людей в нем = в этом движении были кем-то вроде тех образованных анархистов, которые устраивают: «делают» революции), but that beside them there were financiers who were playing for money (но что кроме них были и финансисты, которые играли ради денег). A clever man can make big profits on a falling market (умный делец: «человек» может сделать большие барыши: «крупные прибыли» на падающем рынке), and it suited the book of both classes to set Europe by the ears (и это совпадало с планами обоих классов – поссорить Европу; to suit smb.’s books – совпадать с чьими-л. планами, подходить кому-л.; by the ears – в ссоре: «за уши»).

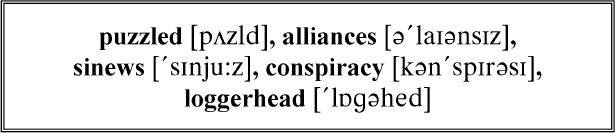

He told me some queer things that explained a lot that had puzzled me (он рассказал мне о некоторых странных событиях, которые объясняли многое из того, что озадачивало меня) – things that happened in the Balkan War (о событиях, которые произошли во время Балканской войны), how one state suddenly came out on top (о том, как одно государство неожиданно победило: «вышло на вершину»; to come out on top – победить /в состязании, и т. п./), why alliances were made and broken (почему союзы заключались и разрывались; to break), why certain men disappeared (почему исчезли определенные люди), and where the sinews of war came from (и откуда взялись материальные средства, необходимые для ведения войны; sinew – сухожилие, жила; деньги, финансы). The aim of the whole conspiracy was to get Russia and Germany at loggerheads (целью всего заговора было довести до ссоры Россию и Германию; loggerhead – олух, болван; to get to loggerheads – /уст./ дойти до драки).

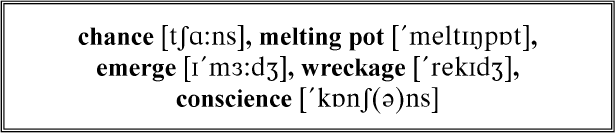

When I asked why (когда я спросил у него, зачем), he said that the anarchist lot thought it would give them their chance (он сказал, что анархисты думали, что это даст им шанс; lot – лот, жребий; группа, компания /каких-л. людей/; to think). Everything would be in the melting-pot (всё оказалось бы в плавильном котле; to melt – таять; плавить; pot – горшок, котелок), and they looked to see a new world emerge (и они надеялись увидеть появление нового мира: «как появляется новый мир»; to look – смотреть, глядеть; ожидать с уверенностью, надеяться). The capitalists would rake in the shekels (капиталисты загребли бы деньги; to rake – сгребать граблями; rake – грабли; shekel – шекель; деньги), and make fortunes by buying up wreckage (и сделали бы состояния, скупив обломки /старого мира/). Capital, he said, had no conscience and no fatherland (у капитала, сказал он, нет совести и нет отечества). I could not help saying that his anarchists seemed to have got left behind a little (я не мог удержаться, чтобы не сказать, что эти его анархисты, казалось, немного отстали; to leave behind – забывать /где-л./; оставлять позади, опережать).

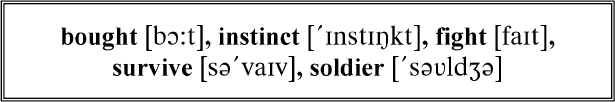

‘Yes and no (и да, и нет),’ he said. ‘They won up to a point (они выиграли в некотором смысле; to win; point – точка; вопрос, дело), but they struck a bigger thing than money (но они нашли нечто гораздо большее, чем деньги; to strike – ударять, бить; находить, наталкиваться), a thing that couldn’t be bought (то, что невозможно купить: «что не может быть куплено»; to buy), the old elemental fighting instincts of man (древние врожденные: «старые природные» бойцовские инстинкты человека). If you’re going to be killed you invent some kind of flag and country to fight for (если вас собираются убить: «если вы собираетесь быть убитыми», вы придумываете что-то вроде флага и страны, за которые /будете/ сражаться; to invent – изобретать, создавать; выдумывать, сочинять), and if you survive you get to love the thing (и если вы выживете, вы начнете любить их; to get to do smth. – /разг./ начинать делать что-л.). Those foolish devils of soldiers have found something they care for (эти глупые солдаты-сорвиголовы обнаружили что-то, что они любят; devil – /эмоц.-усил./ черт; a devil of a fellow – сущий черт, сорвиголова; to care – заботиться; любить, питать интерес), and that has upset the pretty plan laid in Berlin and Vienna (и это расстроило прекрасный план, придуманный в Берлине и Вене; to lay – класть, положить; излагать, представлять /факты, сведения/; to lay plans – разрабатывать планы). But my friends haven’t played their last card by a long sight (но мои друзья еще не разыграли свою последнюю карту, отнюдь; not by a long sight – отнюдь нет!). They’ve gotten the ace up their sleeves (у них есть туз в рукаве), and unless I can keep alive for a month they are going to play it and win (и, если только я не смогу остаться в живых еще на месяц, они разыграют его и выиграют; unless – если не).’

‘But I thought you were dead (но я думал, что вы мертвы),’ I put in (вставил я).

‘Mors janua vitae (смерть – преддверие жизни /лат./),’ he smiled (улыбнулся он). (I recognized the quotation (я узнал эту цитату): it was about all the Latin I knew (это почти вся латынь, которую я знаю; to know).) ‘I’m coming to that (я подхожу к этому), but I’ve got to put you wise about a lot of things first (но сперва мне надо рассказать вам о многих вещах: «сделать вас осведомленным во многих вещах»; wise – мудрый; осведомленный, знающий). If you read your newspaper (если вы читали газету), I guess you know the name of Constantine Karolides (я полагаю, вы знаете имя Константина Каролидеса; to guess – догадываться, предполагать; думать, полагать, считать)?’

I sat up at that (я выпрямился, услышав это: «при этом»; to sit up – садиться, приподниматься /из лежачего положения/; выпрямляться /сидя в кресле и т. п./), for I had been reading about him that very afternoon (потому что я читал о нем в тот самый день).