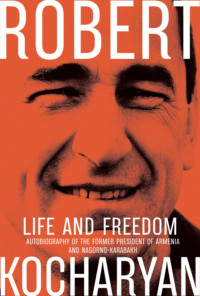

Life and Freedom. The autobiography of the former president of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh

Contrary to my fears, I did pretty well on the exams and was admitted to the university's Department of Power Engineering. I called my father. Mobile phones didn't exist yet, so I had to go to the post office, place an order, indicate the call duration, and sit and wait for the connection to make the long-distance phone call. My father was happy that I got accepted. Despite his usual emotional restraint, I could sense that he was proud that his son would go to college in the capital.

Now I had time to take a breath and look around. When I was in the seventh or eighth grade, I had visited Moscow, but it was a really short trip, and I didn't remember much of it. This time, however, for a young fellow from a small mountain town, Moscow's scale and atmosphere, its vast palatial underground metro, and its entirely different crowd were awe-inspiring. I didn't feel lost; instead, I was happy and proud. I spent the summer days walking around, absorbing the spirit of the capital.

My classes started in the fall. They turned out to be easier than I expected but not too exciting either. Perhaps the reason was that a fascinating and well-educated person, a walking encyclopedia – Kim Grigorian, my brother-in-law – came into my life. I had never met a man of such erudition before, and I haven't, perhaps, ever since then. Kim was also from Stepanakert. He had graduated from Moscow's Textile Institute and headed аn engineering design bureau at some large factory. I stayed at a dorm in Lefortovo but spent all my weekends at my sister and Kim's tiny apartment in Reutov. My informal education began there.

We spent evenings in the kitchen. Kim talked about unusual things. I grew up in a family where the fairness and effectiveness of the Soviet system were never questioned. As an ordinary Soviet boy, the son of a communist, I believed that I lived in the best country in the world. But now, day after day, evening after evening, Kim showed me the reality. I learned about Stalin's repressions and the millions of people who died of starvation during the collectivization. I learned about Red commanders arrested right before World War II and Stalin's secret pact with Hitler to divide Europe.

Kim wasn't an active dissident; he was just a clear thinker who relentlessly criticized the system. Few in the Soviet Union back then understood the horrific realities of Stalin's regime or how stagnant Brezhnev's rule was. Kim found a grateful listener in me and unleashed all these truths upon me. Toward the middle of the night, tired of our long discussions, we listened to jammed Radio Liberty programs or to jazz.

Kim introduced me to a range of literature on politics, philosophy, and theology. These were not samizdat publications, yet their content had a profound impact on reshaping my mindset.

We began with Baruch Spinoza's Theologico-Political Treatise. I had never read anything like it before. It was a very tough but insanely exciting read. The world opened up to me in a different way. I came to believe that only through a social contract, accepted voluntarily and based on reason, could an individual's passions and flaws be reined in. These ideas had little in common with Soviet realities, but I didn't try to tie them together at the time – I was simply absorbing them. Although it is possible that, decades later, when I became president of post-Soviet Armenia, this 17th-century book that I read at the age of 17 subliminally impacted many of my decisions.

Once, Kim gave me a copy of the Bible. It was a small, pocket-sized book with a soft cover that contained 1,000 pages – a miracle by itself. I read it quickly, not understanding why I needed it. I did not become a believer, of course. Still, it shook the ideological framework instilled in every one of us by the Soviet system. The Bible seemed more humanistic than "The Moral Code of the Builder of Communism," posted as visual propaganda in every school's hallways.

Although my conversations with Kim seriously shook me, they didn't turn me into a philosopher or a dissident. They had a cooling effect on my studies, however. Technical sciences didn't offer answers to philosophical questions, and these issues consumed me more and more. I had a feeling that I hadn't chosen the right college, but I continued to attend classes and completed the first semester quite well. At the same time, my social life as a student was thriving. I made friends, and together we walked around Moscow and went to the movies and cafes. There were many options for rest and recreation in the city that distracted us from our studies. The Metelitsa café on Kalinin boulevard (today's Noviy Arbat) was particularly trendy among students for some reason, and going there was considered very chic. On Saturdays, we went to the dance club in our dorm. One of these visits to the dance club ended up being a turning point in my student life.

At the end of May, right before the second semester finals, a new and somewhat arrogant guy showed up at the dance club. He behaved defiantly, believing that he could do anything he wanted and was clearly looking for a fight. I lashed out. Friends tried to stop me by telling me his dad was someone important, and it wasn't worth it. I didn't budge, and a fight broke out. I struck him hard. I didn't hurt him too much, didn't break a bone, but he ended up with a big shiner. I didn't pay too much attention to this: stuff happens – you get all worked up, then you calm down, make peace, and even become friends.

Two days later, I was summoned to the dean's office. They made me write a statement and threatened to expel me. I tried to explain that he had been looking for a fight. It turned out that this guy was related to someone in the institute's leadership. As a result, the dance floor incident got blown out of proportion. They didn't expel me right away, perhaps because the guy's guilt was too obvious: he was extremely drunk and instigated the fight. However, the issue dragged on; I found myself visiting the dean's office over and over, my relationship with the department deteriorated significantly, and my already waning interest in my studies dimmed completely. There was no way I could tell my parents about this incident, and for some reason, I didn't share it with my sister or Kim either.

In the end, I told the dean that I would transfer to another college and asked for a chance to leave on my own volition. He agreed.

It was summer again, another June. One year prior, I had come to Moscow, taken college entrance exams, got accepted, and called my father to tell him that I got in. My father was so proud of his son… Now, I was holding expulsion papers in my hand. The fact itself didn't bother me too much, but I was unbearably ashamed to tell my father, and I couldn't bring myself to talk to him for a long time. I knew that this news would become a real tragedy for him.

But I couldn't delay any longer, and I went to the post office. I gave our home number to the phone operator and sat down to wait for the connection. The time couldn't have crawled any slower. Minutes felt like hours. And finally, far away in the receiver, I heard my father's happy voice through static and crackling – his son was calling!

"Dad, I quit the institute."

My father was overwhelmed with the unexpected news.

"Why? What happened?"

I struggled to find an answer. I couldn't tell him about the conflict, and he wouldn't believe I had flunked my classes – I was always a straight-A student, after all.

"It just didn't work out. I don't want to study anymore. I'll join the army."

My father went silent. He didn't know what to say.

"I'll go to Kharkov."

My mother's brothers lived in Kharkov. I just couldn't go home – I didn't know how to look my father in the eye.

I hung out in Kharkov for a month and then went back to Stepanakert. I could see that my father was upset, but he didn't ask me anything. I was very much avoiding the conversation about my interrupted studies too.

I got a job as a machine operator-assembler at the electrotechnical plant. I worked five days a week, and on weekends, I would head to the mountains with friends, often bringing a gun. Fall, always incredibly picturesque in Karabakh, painted the hills with a range of bright colors. Sometimes, I didn't even feel like hunting, not wanting to interrupt the peace and quiet. Instead, I simply walked the mountain trails. My memories of being a college student in Moscow got pushed further and further back and gradually faded.

CHAPTER 3

THE ARMY

I didn't make any plans for the future; I waited to be called in for military service. All my friends got drafted on November 9, and I wanted to go with them, hoping that we would serve together. But the draft board seemed to have forgotten about me – my records had probably gotten stuck somewhere since I had gone out of town to attend college. So I had to ask for my father's help. He called the military commissar, whom he knew very well, and told him that I wanted to serve immediately. The military commissar was startled. He said, "You are the first to call asking to expedite military service. People usually ask me to help dodge the draft or delay it!" He fulfilled my father's request, and I was drafted right after the November holidays.

I ended up in the railway troops, whose existence I didn't even suspect before. I thought we would crisscross the country by rail performing military tasks. But as it turned out, we were to build those railways for others to travel on. The only thing that differentiated the construction battalions was that we weren't paid to do it. With this, any poetics of performing military service disappeared immediately.

First, I was sent to a boot camp in Cherepovets. The only memorable part of that town for me was the chimneys of its metallurgical plant. All the way to the horizon – chimneys, chimneys, and more chimneys, each spewing smoke of a different color ranging from black to orange. The following day it snowed, and the ground was covered with varying shades of the same smoke. The training center gathered groups from various republics, different regions of the country; there were about 10 of us from Karabakh, and none of my friends were among them.

Boot camp is a special place. A whole lot of guys from the same draft season end up in an unusual setting, where they must understand and get a sense of what military service is going to be like. In part, that understanding comes through adjusting and forming an internal hierarchy. For instance: who sleeps on the top bunk and who sleeps on the bottom, or who is responsible for cleaning the bathrooms. I didn't want to clean bathrooms at all.

It was here that I finally understood the essence of the "natural law" in Spinoza's Political Treatise. Fists, and the perpetual willingness to use them, became the only means of self-assertion. I was in good shape. My years of freestyle wrestling came in very handy, and my courage and will were over the top. Boldness and aggression, which I never thought I had, suddenly surfaced in me. Very soon, I started to get respect. A guy who grew up in a cultured family from an upscale part of a quiet town unexpectedly ended up in a setting where he had to fight for a place in the sun – brutally and without mercy. I faced the kind of reality I was shielded from during my childhood and adolescence. This played a critical role in my self-formation. I acquired the skills necessary to function in unfriendly and even highly aggressive environments. Without these skills, I probably couldn't have faced the ordeals awaiting me in the future.

From boot camp, I was sent to Pushkin, near Leningrad, and later to Vologda. It was the same story: adjusting and self-assertion, but it was much easier to do this time.

This type of service could hardly be called military service. I saw the shooting range only once, and I shot nine rounds there. I didn't see any military hardware, only tractors and dump trucks. For the next two months, I lived a free life in Leningrad. We repaired trailers in the workshops of the Defense Ministry for a month. We lived there, too, and worked hard, but we were free at night. I drove all over Leningrad dressed in a tracksuit. We didn't have any bosses, only a guard – a retired old man. Then I worked at an army farm near Viborg for a month. Together with seven other soldiers, I harvested potatoes and vegetables for our military base. We lived in the local cultural center under my supervision – no marching drills, no army service regulations. Here, too, just like in Pushkin, we worked hard during the day, but at night, we went to the local dance hall, where we were very popular with local girls.

I served my final year in Mongolia – in Darkhan and Erdenet. It was very different from serving in stationary military units. Our command was ordered to form a special battalion to build a railway from Darkhan to Erdenet in order to reach Mongolia's molybdenum mines. Every military base in the railway troops sent several servicemen, according to quotas, to form this new battalion.

To get rid of the troublemakers, commanding officers gave them favorable reviews and assigned them to the newly-formed battalion. I was serving in Vologda at the time and volunteered for the battalion to join my friend, who was number one on the list to be sent away. Kolya, from Bryansk, was our commanding officer's biggest headache. He was awfully rowdy, a regular in the stockade, yet brilliant and well-read. He annoyed the entire command with his very well-written complaint letters to various agencies. He wrote them all the time, triggering multiple inspections to check on the complaints. Our commanding officer was furious, of course.

I remember that during the morning flag assembly, enraged by another inspection, he screamed at the top of his lungs, "We can't find someone to write even a couple of lines for our unit's newspaper, yet this dick composed a whole letter and sent it to none other than the minister of defense himself!" I think our commanding officer was the happiest man in the world to hear that a critical railroad was to be built in Mongolia.

Thus, the new battalion boarded a train and spent the next 10 days getting to its destination. Imagine a crowd of the rowdiest heavy-drinking rebels – some new recruits, some about to be discharged – on a train together for 10 days. No one knew what they were capable of. The adjustment, this time on the road, began right away. We saw our platoon commander only twice – once at the place we boarded and once at the destination, but this time with a big shiner. I don't know how he got it, but I could tell that he had been drinking non-stop. As it turned out, the officers were selected using the same criteria: they were the ones to be gotten rid of. Even though the commanding officer and the political officer were capable professionals, it took a lot of effort to control this bedlam.

We reached our deployment location at night. There was nothing but a bare steppe, but we had to settle there. We put up tents. We had to do everything ourselves: organize our work, get equipment, and build shelters. There were no settlements for many miles around. You could drive for three hours and not see anything except for a couple of yurts and a herd of cattle.

In these harsh and very unusual living and working conditions, soldiers built very different relationships from those on regular stationary military bases. Sticks and carrots didn't work. The stockade was far away in Ulan Bator. There was nowhere to go after dismissal – only wild nature all around us. Our leisure time was built around the high bar, weights, parallel bars, and boxing gloves. There was a pool table set up for the officers in the field, but it remained there only until a sandstorm lifted it 50 meters high and slammed it onto the ground, smashing it to pieces.

Matters were not settled by the army service regulations. Although we were privates, three of us – Gena from Riga, Kolya from Bryansk, and I – ended up at the top of the hierarchy. We were on good terms with the officers, and our detachment was completing tasks ahead of schedule. But enforcing service regulations – the way they did in Moscow or Germany, where soldiers lived in good barracks, had showers, followed precise daily schedules, and were well fed – was impossible.

We didn't have barracks at all – we lived in tents. As the railroad construction progressed, our base moved three times to be closer to the work site. Each time, we had to settle in from scratch. The nature was breathtaking: very unique landscapes, unusual to my eye. Gently sloping mountains that stretched across the steppe underscored the vastness of pristine wilderness. The climate was markedly harsh: -35° centigrade in the winter and 40° during the summer. In May, it was -3° at night and 27° during the day. Yet, we stayed in tents, 30 soldiers in each tent. For heat, we used woodburning stoves with long chimneys. It was cold on the bottom of the bunk bed and scorching hot on the top, where all the earlier recruits slept. With no refrigerators in the steppe, meat would go bad before it could reach us during the summer. So that we wouldn't be eating canned meat all summer, our commanding officer let us put together a fishing brigade, which I joined thanks to my hunting skills. We caught burbots at night in the Orkhon and Selenga rivers for the entire military base and slept during the day. Sometimes we shot antelopes by chasing them down in GAZ-66 trucks, although it wasn't encouraged. This is how the summer went by.

Serving in the army was а priceless character-building life experience for me.

After being discharged, my relationships with my army friends didn't last for too long. We went our separate ways, and long-distance communications back then – without mobile telephone service and social media – required much effort.

CHAPTER 4

SUCCESSION OF CHANGES

Limitchik[4]I was discharged from the army at the end of December, right before New Year's Eve, and made it home for the holidays. By then, all of my friends, classmates, acquaintances, and neighbors of the same age had already returned to Stepanakert, having concluded their military service. The phone rang almost every day. "Oh, you're already here? We have to meet!" I wanted to see everybody, and I met up with someone every day. During one of these get-togethers, I got drunk for the first time. Luckily, I realized it when I was already home.

A month and a half flew by in the blink of an eye.

As I began getting back into civilian life, I pondered what to do next. First, I tried settling down in Moscow. I flew to the capital and moved in with my sister in Reutov. I went to the Moscow Power Engineering Institute. I realized that nothing had changed there, and there was no way I could get re-admitted. So I gave up and began looking for a job. Those like me, who were dismissively called "limitchiks," were drawn in by the prospect of a Moscow residence status. We were actively encouraged to join construction projects, Moscow's Metrostroy transport authority, or work in the factories – jobs that weren't too popular with Muscovites. The capital grew rapidly, and working hands were desperately needed. Newspapers were full of laborer job ads.

Before long, I got a job as a laborer at the Reinforced Concrete Plant (RCP) #11, not too far away from the Hammer and Sickle metro station. I had no idea what RCP was – I chose it by chance. I wanted to get a construction job, and my sister researched all the ads and found a company that, by Moscow standards, was not too far away from home. Besides, they provided decent housing in a newly constructed high-rise apartment complex, which became the determining factor.

This is how I became a concrete worker. When people ask me about this period, I joke that it was a great experience interacting with Moscow's working class and living in a worker dormitory. It required considerable self-control to resist getting drunk on Sundays, like everyone else. Otherwise, my neighbors were good people.

We were manufacturing concrete columns used in the construction of multi-story residential buildings. It was a labor-intensive process: first, we installed the rebar frame in the mold of the future column, put it on a concrete vibrator, and poured in the concrete. Then, the crane operator placed the contraption in the drying chamber, where it stayed overnight. The following morning, the molds were removed. Finally, the ready column was cured for a couple of days and transported to the construction site.

It was strenuous physical labor, but I was fit, and I managed well. Besides, it paid well – 200 rubles net was considered a decent salary. Moreover, I never had a habit of putting money away, so I made a good living as a single guy.

Our dorm in Novogireyevo was only one commuter train stop away from Reutov, where my sister and her husband lived, so my interaction with Kim continued. I didn't participate in sports that year – my work provided more than enough exercise. In a worker dorm in the 70s, there was nowhere to work out anyway.

So, another year passed in a blur, without any significant developments. I mostly worked and educated myself, reading a lot. But I had always read a lot, even as a child, except for my time in the army.

The library in Mongolia was small, and I read everything remotely interesting there. Besides, life in the army was not particularly conducive to reading, just like jail. Later, during the Karabakh conflict, one of our activists – Murad Petrosian, who had spent a decade in jail – cited Lenin all the time. Once, I asked him, "Look, with your life story, why are you citing classicists of Marxism?" He said that he learned Lenin by heart simply because there was nothing else to read at the jail's library.

I became more and more fascinated with philosophy. I read the original authors, and if I read fiction, it was by authors like Anatole France, who artfully wove philosophy into the narrative fabric. I discussed what I read with Kim in detail. I marvel at myself now – how did I read all that? How could I get through boring authors like Francis Bacon? But back then, I read them unremittingly, excitedly, and enthusiastically. I read works by every author I could find, everything that had been published.

I was quite taken with La Mettrie. Perhaps he isn't all that profound a thinker, but he does have an engaging writing style. And, of course, I read the classics: Rousseau, Montaigne, Hegel, Kant, and Nietzsche in samizdat. I liked Hegel's earliest work, Life of Jesus, which is easy to read. Everything else by him is a nightmare! Every sentence takes up nearly half a page and requires multiple readings to grasp its meaning, which is often quite simple. I made it through Hegel's Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion. Still, I got stuck in the very beginning of his Elements of the Philosophy of Right, perhaps, because of his writing style. German philosophers left an impression on me with their burdensome prose, as if they intentionally complicated the language to emphasize the scientific nature of their views. Perhaps my torments while reading Hegel are the reason behind my overly concise speaking style.

I'm kidding, of course.

Much of what I read was soon forgotten. I read philosophy for fun; I didn't read it to study it. But I am sure it wasn't a waste of time: it gave my brain a good workout, and left a lasting impact on my personality. I felt a strong need to develop intellectually, to learn something new. Perhaps I subconsciously satiated my thirst for knowledge with intensive self-education while I wasn't attending college.

I didn't manage to make many friends in Moscow. I wasn't friends with anyone at work, and in reality, I couldn't be friends with them. They were good guys, but almost all of them loved to drink. They ran to the nearest bar or liquor store to buy a bottle as soon as they got their paychecks. That lifestyle was foreign to my habits and my understanding of life. However, I became friends with a neighbor from the apartment complex next to mine. His name was David Voronov. He was intelligent and cultured – a lot older than me – and at that time, he was already divorced. He was passionate about dogs and equally passionate about postage stamps. David constantly bought, sold, and traded stamps – "speculated" as they said back then. It was considered semi-legal, and one could end up in jail for speculating. He tried recruiting me, and I even learned a little about stamps, but it didn't go beyond curiosity. I wasn't attracted to buying and selling.