A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms

This morning the puppeteers were doing the tale of Florian and Jonquil. The fat Dornishwoman was working Florian in his armor made of motley, while the tall girl held Jonquil’s strings. “You are no knight,” she was saying as the puppet’s mouth moved up and down. “I know you. You are Florian the Fool.”

“I am, my lady,” the other puppet answered, kneeling. “As great a fool as ever lived, and as great a knight as well.”

“A fool and a knight?” said Jonquil. “I have never heard of such a thing.”

“Sweet lady,” said Florian, “all men are fools, and all men are knights, where women are concerned.”

It was a good show, sad and sweet both, with a sprightly sword fight at the end, and a nicely painted giant. When it was over, the fat woman went amongst the crowd to collect coins while the girl packed away the puppets.

Dunk collected Egg and went up to her.

“M’lord?” she said, with a sideways glance and a half smile. She was a head shorter than he was, but still taller than any other girl he had ever seen.

“That was good,” Egg enthused. “I like how you make them move, Jonquil and the dragon and all. I saw a puppet show last year, but they moved all jerky. Yours are more smooth.”

“Thank you,” she said to the boy politely.

Dunk said, “Your figures are well carved too. The dragon, especially. A fearsome beast. You make them yourself?”

She nodded. “My uncle does the carving. I paint them.”

“Could you paint something for me? I have the coin to pay.” He slipped the shield off his shoulder and turned it to show her. “I need to paint something over the chalice.”

The girl glanced at the shield, then at him. “What would you want painted?”

Dunk had not considered that. If not the old man’s winged chalice, what? His head was empty. Dunk the lunk, thick as a castle wall. “I don’t … I’m not certain.” His ears were turning red, he realized miserably. “You must think me an utter fool.”

She smiled. “All men are fools, and all men are knights.”

“What color paint do you have?” he asked, hoping that might give him an idea.

“I can mix paints to make any color you want.”

The old man’s brown had always seemed drab to Dunk. “The field should be the color of sunset,” he said suddenly. “The old man liked sunsets. And the device …”

“An elm tree,” said Egg. “A big elm tree, like the one by the pool, with a brown trunk and green branches.”

“Yes,” Dunk said. “That would serve. An elm tree … but with a shooting star above. Could you do that?”

The girl nodded. “Give me the shield. I’ll paint it this very night and have it back to you on the morrow.”

Dunk handed it over. “I am called Ser Duncan the Tall.”

“I’m Tanselle,” she laughed. “Tanselle Too-Tall, the boys used to call me.”

“You’re not too tall,” Dunk blurted out. “You’re just right for …” He realized what he had been about to say, and blushed furiously.

“For?” said Tanselle, cocking her head inquisitively.

“Puppets,” he finished lamely.

The first day of the tourney dawned bright and clear. Dunk bought a sackful of foodstuffs, so they were able to break their fast on goose eggs, fried bread, and bacon, but when the food was cooked he found he had no appetite. His belly felt hard as a rock, even though he knew he would not ride today. The right of first challenge would go to knights of higher birth and greater renown, to lords and their sons and champions from other tourneys.

Egg chattered all through their breakfast, talking of this man and that man and how they might fare. He was not japing me when he said he knew every good knight in the Seven Kingdoms, Dunk thought ruefully. He found it humbling to listen so intently to the words of a scrawny orphan boy, but Egg’s knowledge might serve him should he face one of these men in a tilt.

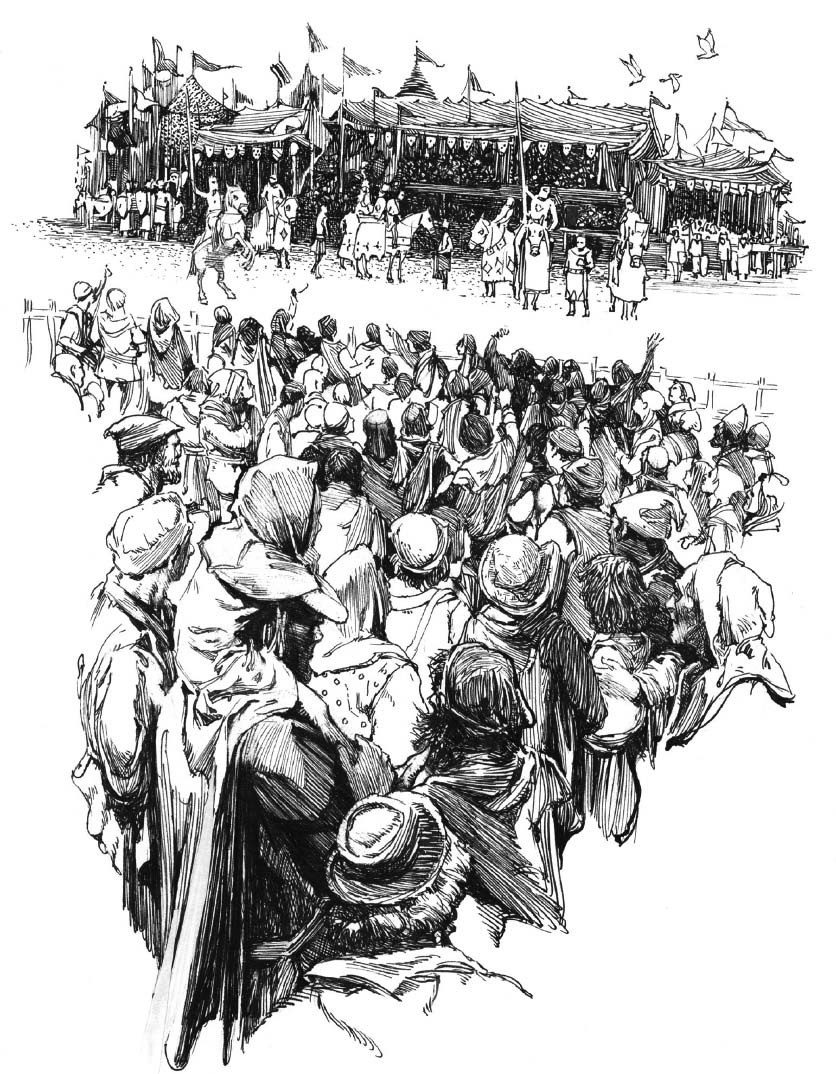

The meadow was a churning mass of people, all trying to elbow their way closer for a better view. Dunk was as good an elbower as any, and bigger than most. He squirmed forward to a rise six yards from the fence. When Egg complained that all he could see were arses, Dunk sat the boy on his shoulders.

Across the field, the viewing stand was filling up with highborn lords and ladies, a few rich townfolk, and a score of knights who had decided not to compete today. Of Prince Maekar he saw no sign, but he recognized Prince Baelor at Lord Ashford’s side. Sunlight flashed golden off the shoulder clasp that held his cloak and the slim coronet about his temples, but otherwise he dressed far more simply than most of the other lords. He does not look a Targaryen in truth, with that dark hair. Dunk said as much to Egg.

“It’s said he favors his mother,” the boy reminded him. “She was a Dornish princess.”

The five champions had raised their pavilions at the north end of the lists with the river behind them. The smallest two were orange, and the shields hung outside their doors displayed the white sun-and-chevron. Those would be Lord Ashford’s sons Androw and Robert, brothers to the fair maid. Dunk had never heard other knights speak of their prowess, which meant they would likely be the first to fall.

Beside the orange pavilions stood one of deep-dyed green, much larger. The golden rose of Highgarden flapped above it, and the same device was emblazoned on the great green shield outside the door. “That’s Leo Tyrell, Lord of Highgarden,” said Egg.

“I knew that,” said Dunk, irritated. “The old man and I served at Highgarden before you were ever born.” He hardly remembered that year himself, but Ser Arlan had often spoken of Leo Longthorn, as he was sometimes called; a peerless jouster, for all the silver in his hair. “That must be Lord Leo beside the tent, the slender greybeard in green and gold.”

“Yes,” said Egg. “I saw him at King’s Landing once. He’s not one you’ll want to challenge, ser.”

“Boy, I do not require your counsel on who to challenge.”

The fourth pavilion was sewn together from diamond-shaped pieces of cloth, alternating red and white. Dunk did not know the colors, but Egg said they belonged to a knight from the Vale of Arryn named Ser Humfrey Hardyng. “He won a great melee at Maidenpool last year, ser, and overthrew Ser Donnel of Duskendale and the Lords Arryn and Royce in the lists.”

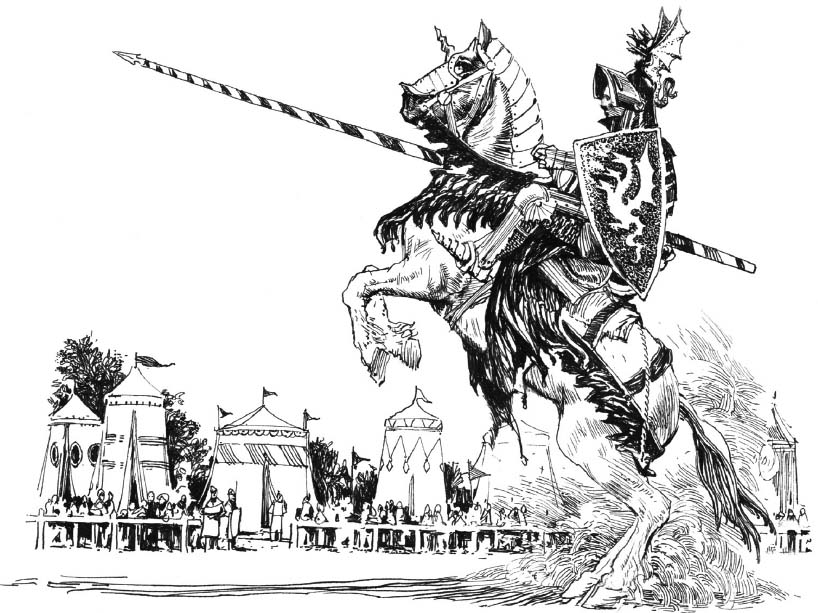

The last pavilion was Prince Valarr’s. Of black silk it was, with a line of pointed scarlet pennons hanging from its roof like long red flames. The shield on its stand was glossy black, emblazoned with the three-headed dragon of House Targaryen. One of the Kingsguard knights stood beside it, his shining white armor stark against the black of the tent cloth. Seeing him there, Dunk wondered whether any of the challengers would dare to touch the dragon shield. Valarr was the king’s grandson, after all, and son to Baelor Breakspear.

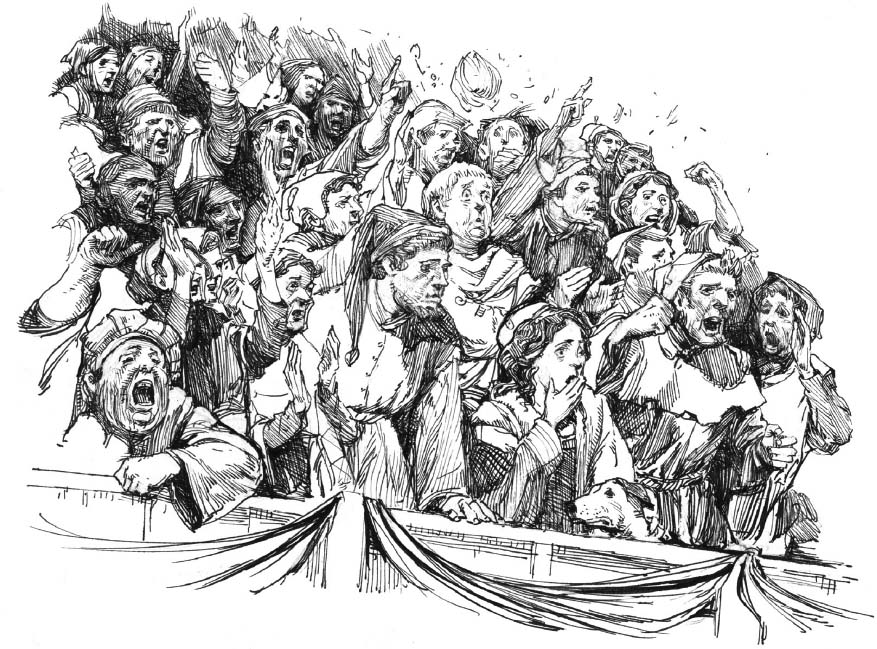

He need not have worried. When the horns blew to summon the challengers, all five of the maid’s champions were called forth to defend her. Dunk could hear the murmur of excitement in the crowd as the challengers appeared one by one at the south end of the lists. Heralds boomed out the name of each knight in turn. They paused before the viewing stand to dip their lances in salute to Lord Ashford, Prince Baelor, and the fair maid, then circled to the north end of the field to select their opponents. The Grey Lion of Casterly Rock struck the shield of Lord Tyrell, while his golden-haired heir Ser Tybolt Lannister challenged Lord Ashford’s eldest son. Lord Tully of Riverrun tapped the diamond-patterned shield of Ser Humfrey Hardyng, Ser Abelar Hightower knocked upon Valarr’s, and the younger Ashford was called out by Ser Lyonel Baratheon, the knight they called the Laughing Storm.

The challengers trotted back to the south end of the lists to await their foes: Ser Abelar in silver and smoke colors, a stone watchtower on his shield, crowned with fire; the two Lannisters all crimson, bearing the golden lion of Casterly Rock; the Laughing Storm shining in cloth-of-gold, with a black stag on breast and shield and a rack of iron antlers on his helm; Lord Tully wearing a striped blue-and-red cloak clasped with a silver trout at each shoulder. They pointed their twelve-foot lances skyward, the gusty winds snapping and tugging at the pennons.

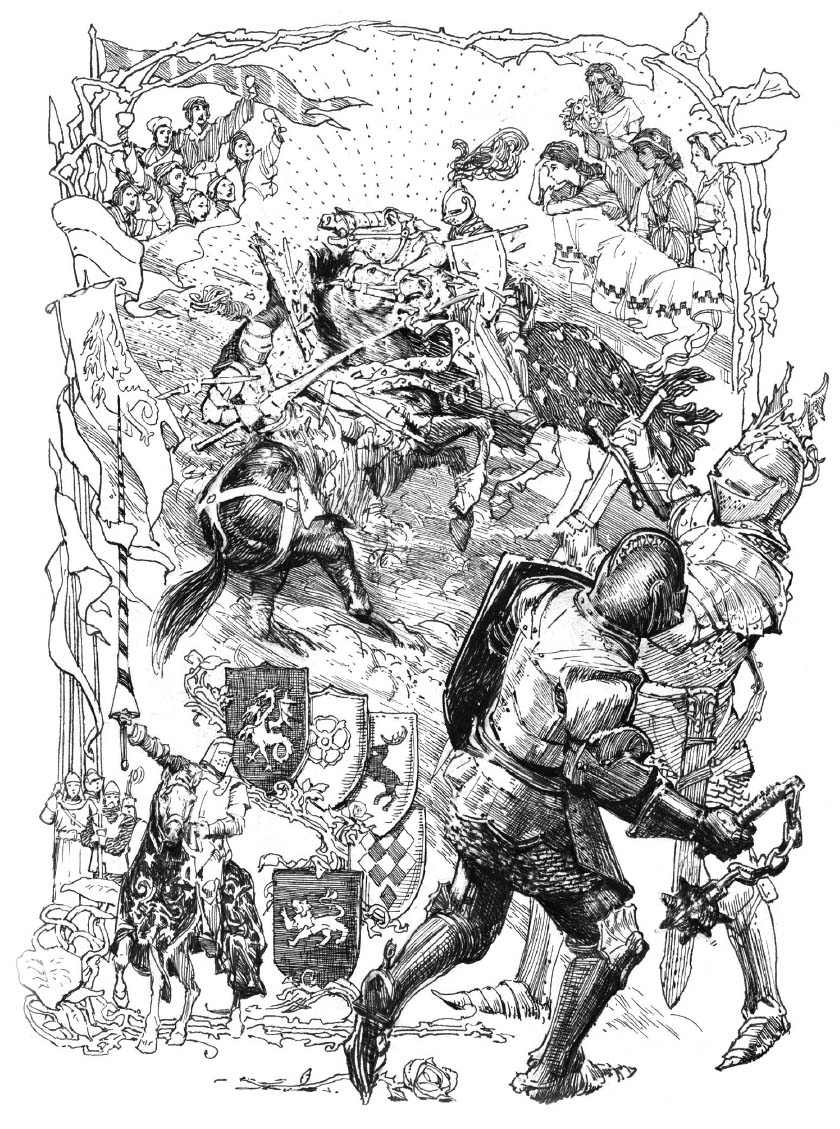

At the north end of the field, squires held brightly barded destriers for the champions to mount. They donned their helms and took up lance and shield, in splendor the equal of their foes: the Ashfords’ billowing orange silks, Ser Humfrey’s red-and-white diamonds, Lord Leo on his white charger with green satin trappings patterned with golden roses, and of course Valarr Targaryen. The Young Prince’s horse was black as night, to match the color of his armor, lance, shield, and trappings. Atop his helm was a gleaming three-headed dragon, wings spread, enameled in a rich red; its twin was painted upon the glossy black surface of his shield. Each of the defenders had a wisp of orange silk knotted about an arm, favors bestowed by the fair maid.

As the champions trotted into position, Ashford Meadow grew almost still. Then a horn sounded, and stillness turned to tumult in half a heartbeat. Ten pairs of gilded spurs drove into the flanks of ten great warhorses, a thousand voices began to scream and shout, forty ironshod hooves pounded and tore the grass, ten lances dipped and steadied, the field seemed almost to shake, and champions and challengers came together in a rending crash of wood and steel. In an instant, the riders were beyond each other, wheeling about for another pass. Lord Tully reeled in his saddle but managed to keep his seat. When the commons realized that all ten of the lances had broken, a great roar of approval went up. It was a splendid omen for the success of the tourney, and a testament to the skill of the competitors.

Squires handed fresh lances to the jousters to replace the broken ones they cast aside, and once more the spurs dug deep. Dunk could feel the earth trembling beneath the soles of his feet. Atop his shoulders, Egg shouted happily and waved his pipestem arms. The Young Prince passed nearest to them. Dunk saw the point of his black lance kiss the watchtower on his foe’s shield and slide off to slam into his chest, even as Ser Abelar’s own lance burst into splinters against Valarr’s breastplate. The grey stallion in the silver-and-smoke trappings reared with the force of the impact, and Ser Abelar Hightower was lifted from his stirrups and dashed violently to the ground.

Lord Tully was down as well, unhorsed by Ser Humfrey Hardyng, but he sprang up at once and drew his longsword, and Ser Humfrey cast aside his lance – unbroken – and dismounted to continue their fight afoot. Ser Abelar was not so spritely. His squire ran out, loosened his helm, and called for help, and two serving men lifted the dazed knight by the arms to help him back to his pavilion. Elsewhere on the field, the six knights who had remained ahorse were riding their third course. More lances shattered, and this time Lord Leo Tyrell aimed his point so expertly he ripped the Grey Lion’s helm cleanly off his head. Barefaced, the Lord of Casterly Rock raised his hand in salute and dismounted, yielding the match. By then Ser Humfrey had beaten Lord Tully into surrender, showing himself as skilled with a sword as he was with a lance.

Tybolt Lannister and Androw Ashford rode against each other thrice more before Ser Androw finally lost shield, seat, and match all at once. The younger Ashford lasted even longer, breaking no less than nine lances against Ser Lyonel Baratheon, the Laughing Storm. Champion and challenger both lost their saddles on their tenth course, only to rise together to fight on, sword against mace. Finally a battered Ser Robert Ashford admitted defeat, but on the viewing stand his father looked anything but dejected. Both Lord Ashford’s sons had been ushered from the ranks of the champions, it was true, but they had acquitted themselves nobly against two of the finest knights in the Seven Kingdoms.

I must do even better, though, Dunk thought as he watched victor and vanquished embrace and walk together from the field. It is not enough for me to fight well and lose. I must win at least the first challenge, or I lose all.

Ser Tybolt Lannister and the Laughing Storm would now take their places amongst the champions, replacing the men they had defeated. Already the orange pavilions were coming down. A few feet away, the Young Prince sat at his ease in a raised camp chair before his great black tent. His helm was off. He had dark hair like his father, but a bright streak ran through it. A serving man brought him a silver goblet and he took a sip. Water, if he is wise, Dunk thought, wine if not. He found himself wondering if Valarr had indeed inherited a measure of his father’s prowess, or whether it had only been that he had drawn the weakest opponent.

A fanfare of trumpets announced that three new challengers had entered the lists. The heralds shouted their names. “Ser Pearse of House Caron, Lord of the Marches.” He had a silver harp emblazoned on his shield, though his surcoat was patterned with nightingales. “Ser Joseth of House Mallister, from Seagard.” Ser Joseth sported a winged helm; on his shield, a silver eagle flew across an indigo sky. “Ser Gawen of House Swann, Lord of Stonehelm on the Cape of Wrath.” A pair of swans, one black and one white, fought furiously on his arms. Lord Gawen’s armor, cloak, and horse bardings were a riot of black and white as well, down to the stripes on his scabbard and lance.

Lord Caron, harper and singer and knight of renown, touched the point of his lance to Lord Tyrell’s rose. Ser Joseth thumped on Ser Humfrey Hardyng’s diamonds. And the black-and-white knight, Lord Gawen Swann, challenged the black prince with the white guardian. Dunk rubbed his chin. Lord Gawen was even older than the old man, and the old man was dead. “Egg, who is the least dangerous of these challengers?” he asked the boy on his shoulders, who seemed to know so much of these knights.

“Lord Gawen,” the boy said at once. “Valarr’s foe.”

“Prince Valarr,” he corrected. “A squire must keep a courteous tongue, boy.”

The three challengers took their places as the three champions mounted up. Men were making wagers all around them and calling out encouragement to their choices, but Dunk had eyes only for the prince. On the first pass he struck Lord Gawen’s shield a glancing blow, the blunted point of the lance sliding aside just as it had with Ser Abelar Hightower, only this time it was deflected the other way, into empty air. Lord Gawen’s own lance broke clean against the prince’s chest, and Valarr seemed about to fall for an instant before he recovered his seat.

The second time through the lists, Valarr swung his lance left, aiming for his foe’s breast, but struck his shoulder instead. Even so, the blow was enough to make the older knight lose his lance. One arm flailed for balance and Lord Gawen fell. The Young Prince swung from the saddle and drew his sword, but the fallen man waved him off and raised his visor. “I yield, Your Grace,” he called. “Well fought.” The lords in the viewing stand echoed him, shouting, “Well fought! Well fought!” as Valarr knelt to help the grey-haired lord to his feet.

“It was not either,” Egg complained.

“Be quiet, or you can go back to camp.”

Farther away, Ser Joseth Mallister was being carried off the field unconscious, while the harp lord and the rose lord were going at each other lustily with blunted longaxes, to the delight of the roaring crowd. Dunk was so intent on Valarr Targaryen that he scarcely saw them. He is a fair knight, but no more than that, he found himself thinking. I would have a chance against him. If the gods were good, I might even unhorse him, and once afoot my weight and strength would tell.

“Get him!” Egg shouted merrily, shifting his seat on Dunk’s shoulders in his excitement. “Get him! Hit him! Yes! He’s right there, he’s right there!” It seemed to be Lord Caron he was cheering on. The harper was playing a different sort of music now, driving Lord Leo back and back as steel sang on steel. The crowd seemed almost equally divided between them, so cheers and curses mingled freely in the morning air. Chips of wood and paint were flying from Lord Leo’s shield as Lord Pearse’s axe knocked the petals off his golden rose, one by one, until the shield finally shattered and split. But as it did, the axehead hung up for an instant in the wood … and Lord Leo’s own axe crashed down on the haft of his foe’s weapon, breaking it off not a foot from his hand. He cast aside his broken shield, and suddenly he was the one on the attack. Within moments, the harper knight was on one knee, singing his surrender.

For the rest of the morning and well into the afternoon, it was more of the same, as challengers took the field in twos and threes, and sometimes five together. Trumpets blew, the heralds called out names, warhorses charged, the crowd cheered, lances snapped like twigs, and swords rang against helms and mail. It was, smallfolk and high lord alike agreed, a splendid day of jousting. Ser Humfrey Hardyng and Ser Humfrey Beesbury, a bold young knight in yellow and black stripes with three beehives on his shield, splintered no less than a dozen lances apiece in an epic struggle the smallfolk soon began calling The Battle of Humfrey. Ser Tybolt Lannister was unhorsed by Ser Jon Penrose and broke his sword in his fall, but fought back with shield alone to win the bout and remain a champion. One-eyed Ser Robyn Rhysling, a grizzled old knight with a salt-and-pepper beard, lost his helm to Lord Leo’s lance in their first course, yet refused to yield. Three times more they rode at each other, the wind whipping Ser Robyn’s hair while the shards of broken lances flew round his bare face like wooden knives, which Dunk thought all the more wondrous when Egg told him that Ser Robyn had lost his eye to a splinter from a broken lance not five years earlier. Leo Tyrell was too chivalrous to aim another lance at Ser Robyn’s unprotected head, but even so, Rhysling’s stubborn courage (or was it folly?) left Dunk astounded. Finally the Lord of Highgarden struck Ser Robyn’s breastplate a solid thump right over the heart and sent him cartwheeling to the earth.

Ser Lyonel Baratheon also fought several notable matches. Against lesser foes, he would often break into booming laughter the moment they touched his shield and laugh all the time he was mounting and charging and knocking them from their stirrups. If his challengers wore any sort of crest on their helm, Ser Lyonel would strike it off and fling it into the crowd. The crests were ornate things, made of carved wood or shaped leather, and sometimes gilded and enameled or even wrought in pure silver, so the men he beat did not appreciate this habit, though it made him a great favorite of the commons.

Before long, only crestless men were choosing him. As loud and often as Ser Lyonel laughed down a challenger, though, Dunk thought the day’s honors should go to Ser Humfrey Hardyng, who humbled fourteen knights, each one of them formidable.

Meanwhile the Young Prince sat outside his black pavilion, drinking from his silver goblet and rising from time to time to mount his horse and vanquish yet another undistinguished foe. He had won nine victories, but it seemed to Dunk that every one was hollow. He is beating old men and upjumped squires, and a few lords of high birth and low skill. The truly dangerous men are riding past his shield as if they do not see it.

Late in the day, a brazen fanfare announced the entry of a new challenger to the lists. He rode in on a great red charger whose black bardings were slashed to reveal glimpses of yellow, crimson, and orange beneath. As he approached the viewing stand to make his salute, Dunk saw the face beneath the raised visor, and recognized the prince he’d met in Lord Ashford’s stables.

Egg’s legs tightened around his neck. “Stop that,” Dunk snapped, yanking them apart. “Do you mean to choke me?”

“Prince Aerion Brightflame,” a herald called. “Of the Red Keep of King’s Landing, son of Maekar, Prince of Summerhall of House Targaryen, grandson to Daeron the Good, the Second of His Name, King of the Andals, the Rhoynar, and the First Men, and Lord of the Seven Kingdoms.”

Aerion bore a three-headed dragon on his shield, but it was rendered in colors much more vivid than Valarr’s; one head was orange, one yellow, one red, and the flames they breathed had the sheen of gold leaf. His surcoat was a swirl of smoke and fire woven together, and his blackened helm was surmounted by a crest of red enamel flames.

After a pause to dip his lance to Prince Baelor, a pause so brief that it was almost perfunctory, he galloped to the north end of the field, past Lord Leo’s pavilion and the Laughing Storm’s, slowing only when he approached Prince Valarr’s tent. The Young Prince rose and stood stiffly beside his shield, and for a moment Dunk was certain that Aerion meant to strike it … but then he laughed and trotted past, and banged his point hard against Ser Humfrey Hardyng’s diamonds. “Come out, come out, little knight,” he sang in a loud clear voice, “it’s time you faced the dragon.”

Ser Humfrey inclined his head stiffly to his foe as his destrier was brought out, and then ignored him while he mounted, fastened his helm, and took up lance and shield. The spectators grew quiet as the two knights took their places. Dunk heard the clang of Prince Aerion’s dropping his visor. The horn blew.

Ser Humfrey broke slowly, building speed, but his foe raked the red charger with both spurs, coming hard. Egg’s legs tightened again. “Kill him!” he shouted suddenly. “Kill him, he’s right there, kill him, kill him, kill him!” Dunk was not certain which of the knights he was shouting to.

Prince Aerion’s lance, gold-tipped and painted in stripes of red, orange, and yellow, swung down across the barrier. Low, too low, thought Dunk the moment he saw it. He’ll miss the rider and strike Ser Humfrey’s horse, he needs to bring it up. Then, with dawning horror, he began to suspect that Aerion intended no such thing. He cannot mean to …

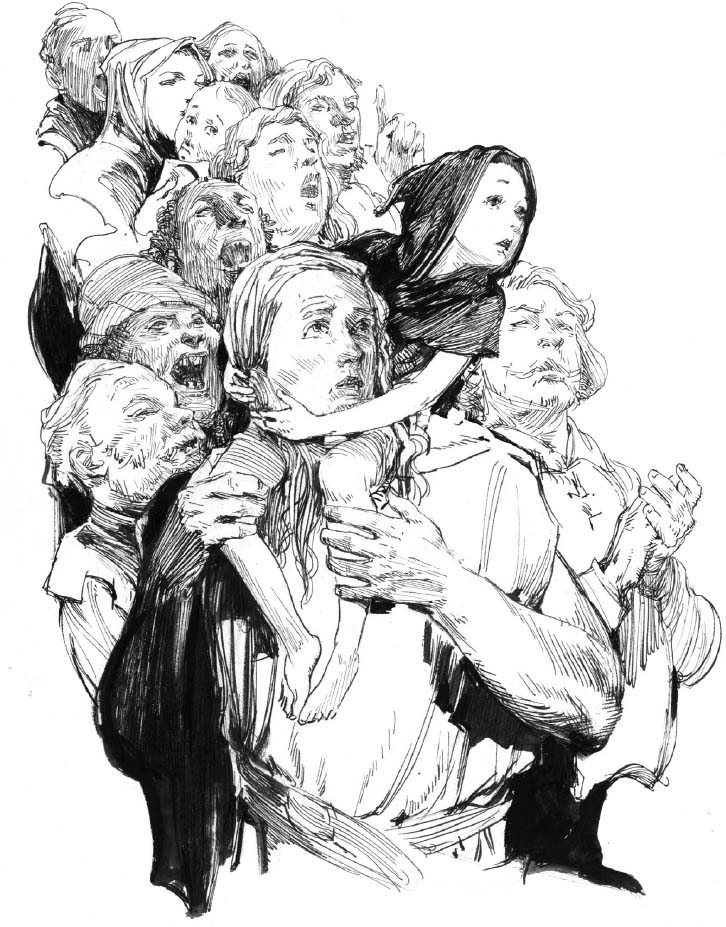

At the last possible instant, Ser Humfrey’s stallion reared away from the oncoming point, eyes rolling in terror, but too late. Aerion’s lance took the animal just above the armor that protected his breastbone, and exploded out of the back of his neck in a gout of bright blood. Screaming, the horse crashed sideways, knocking the wooden barrier to pieces as he fell. Ser Humfrey tried to leap free, but a foot caught in a stirrup and they heard his shriek as his leg was crushed between the splintered fence and falling horse.

All of Ashford Meadow was shouting. Men ran onto the field to extricate Ser Humfrey, but the stallion, dying in agony, kicked at them as they approached. Aerion, having raced blithely around the carnage to the end of the lists, wheeled his horse and came galloping back. He was shouting too, though Dunk could not make out the words over the almost human screams of the dying horse. Vaulting from the saddle, Aerion drew his sword and advanced on his fallen foe. His own squires and one of Ser Humfrey’s had to pull him back. Egg squirmed on Dunk’s shoulders. “Let me down,” the boy said. “The poor horse, let me down.”

Dunk felt sick himself. What would I do if such a fate befell Thunder? A man-at-arms with a poleaxe dispatched Ser Humfrey’s stallion, ending the hideous screams. Dunk turned and forced his way through the press. When he came to open ground, he lifted Egg off his shoulders. The boy’s hood had fallen back and his eyes were red. “A terrible sight, aye,” he told the lad, “but a squire must needs be strong. You’ll see worse mishaps at other tourneys, I fear.”