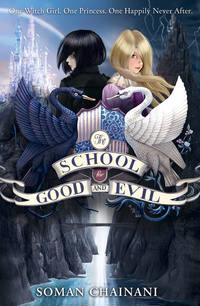

The School for Good and Evil

Falling too fast to scream, Agatha whizzed through chutes, ping-ponged through pipes, and slid down vents until she somersaulted through a grate and landed on a beanstalk.

She hugged the thick green trunk, thankful she was still in one piece. But as she looked around, Agatha saw she wasn’t in a garden or forest or anywhere else a beanstalk is supposed to be. She was in a dark room with high ceilings, filled with paintings, sculptures, and glass cases. Her eyes found the frosted doors in the corner, gilded words etched in glass:

THE GALLERY OF GOOD

Agatha inched down the beanstalk until her clumps touched marble floor.

A mural blanketed the long wall with a panoramic view of a soaring gold castle and a dashing prince and beautiful princess wedded beneath its gleaming arch, as thousands of spectators jingled bells and danced in celebration. Blessed by a brilliant sun, the virtuous couple kissed, while baby angels hovered above, showering them with red and white roses. High above the scene, shiny gold block letters peeked out from behind clouds, stretching from one end of the mural to the other:

EVERAFTER

Agatha grimaced. She had always mocked Sophie for believing in Happily Ever After. (“Who wants to be happy all the time?”) But looking at the mural, she had to admit this school did a spookily good job of selling the idea.

She peered into a glass case, holding a thin booklet of flowery handwriting with a plaque next to it: SNOW WHITE, ANIMAL FLUENCY EXAM (LETITIA OF MAIDENVALE). In the next cases, she found the blue cape of a boy who became Cinderella’s prince, Red Riding Hood’s dorm pillow, the Little Match Girl’s diary, Pinocchio’s pajamas, and other remnants of star students who presumably went on to weddings and castles. On the walls, she scanned more drawings of Ever After by former students, a School History exhibit, banners celebrating iconic victories, and a wall labeled “Class Captain,” stacked with portraits of students from each class. The museum got darker as it went on, so Agatha used one of her matches to light a lamp. That’s when she saw the dead animals.

Dozens of taxidermied creatures loomed over her, stuffed and mounted on rosy pink walls. She dusted off their plaques to find the booted Master Cat, Cinderella’s favorite rat, Jack’s sold-off cow, stamped with the names of children who weren’t good enough to become heroes or sidekicks or servants. No Happily Ever After for this lot. Just hooks in a museum. Agatha felt their eerie, glass-eyed stares and turned away. Only then did she see the plaque gleaming on the beanstalk. HOLDEN OF RAINBOW GALE. That wretched plant had once been a boy.

Agatha’s blood ran cold. All these stories she had never believed in. But they were painfully real now. In two hundred years, no kidnapped child had ever made it back to Gavaldon. What made her think she and Sophie would be the first? What made her think they wouldn’t end up a raven or a rosebush?

Then she remembered what made them different from all the rest.

We have each other.

They had to work together to break this curse. Or they’d both end up fossils of a fairy tale.

Agatha found her attention drawn to a corner nook, with a row of paintings by the same artist, depicting the same scenes: children reading storybooks, in hazy, impressionistic colors. As she neared the paintings, her eyes grew wider. Because she recognized where all these children were.

They were in Gavaldon.

She moved from first painting to last, with reading children set against the familiar hills and lake, crooked clock tower and rickety church, even the shadow of a house on Graves Hill. Agatha felt stabs of homesickness. She had mocked the children as batty and delusional. But in the end, they had known what she didn’t—that the line between stories and real life is very thin indeed.

Then she came to the last painting, which wasn’t like the others at all. In this one, raging children heaved their storybooks into a bonfire in the square and watched them burn. All around them, the dark forest went up in flames, filling the sky with violent red and black smoke. Staring at it, Agatha felt a chill up her spine.

Voices. She dove behind a giant pumpkin carriage, hitting her head on a plaque. HEINRICH OF NETHERWOOD. Agatha gagged.

Two teachers entered the museum, an older woman in a chartreuse high-necked dress, speckled with iridescent green beetle wings, and a younger woman in a pointy-shouldered purple gown that slunk behind her. The woman in chartreuse had a grandmotherly beehive of white hair, but luminous skin and calm brown eyes. The woman in purple had black hair yanked in a long braid, amethyst eyes, and bloodless skin stretched over bones like a drum.

“He’s tampering with the tales, Clarissa,” the one in purple said.

“The School Master can’t control the Storian, Lady Lesso,” Clarissa returned.

“He’s on your side and you know it,” Lady Lesso seethed.

“He’s not on anyone’s side—” Clarissa stopped short. So did Lady Lesso.

Agatha saw what they were looking at. The last painting.

“I see you’ve welcomed another of Professor Sader’s delusions,” Lady Lesso said.

“It is his gallery,” Clarissa sighed.

Lady Lesso’s eyes flashed. Magically, the painting tore off the wall and landed behind a glass case, inches from Agatha’s head.

“This is why they’re not in your school’s gallery,” said Clarissa.

“Anyone who believes the Reader Prophecy is a fool,” hissed Lady Lesso. “Including the School Master.”

“A School Master must protect the balance,” Clarissa said gently. “He sees Readers as part of that balance. Even if you and I cannot understand.”

“Balance!” scoffed Lady Lesso. “Then why hasn’t Evil won a tale since he took over? Why hasn’t Evil defeated Good in two hundred years?”

“Perhaps my students are just better educated,” said Clarissa.

Lady Lesso glowered and walked away. Swishing her finger, Clarissa moved the painting back into place and scurried to keep up.

“Maybe your new Reader will prove you wrong,” she said.

Lady Lesso snorted. “I hear she wears pink.”

Agatha listened to their footsteps go quiet.

She looked up at the dented painting. The children, the bonfire, Gavaldon burning to the ground. What did it all mean?

Twinkly flutters echoed through the air. Before she could move, glowing fairies burst in, searching every crevice like flashlights. Far across the museum, Agatha saw the doors through which the two teachers had left. Just when the fairies reached the pumpkin, she sprinted for it. The fairies squealed in surprise as she slid between three stuffed bears, threw open the doors—

Pink-dressed classmates streamed through the foyer in two perfect lines. As they held hands and giggled, the best of friends, Agatha felt familiar shame rise. Everything in her body told her to shut the door again and hide. But this time instead of thinking of all the friends she didn’t have, Agatha thought about the one she did.

The fairies swooped in a second later, but all they found were princesses on their way to a Welcoming. As they hovered furiously above, hunting for signs of guilt, Agatha slipped into the pink parade, put on a smile . . . and tried to blend.

Despite her ghastly new uniform, Sophie had no intention of sitting with Evil. One look at the Good girls’ glossy hair, dazzling smiles, chic pink dresses, and she knew she had found her sisters. If the fairies wouldn’t rescue her, surely her fellow princesses would. With villains shoving her along, she tried to get the Good girls’ attention, but they were ignoring her side of the theater. Finally Sophie battled her way to the aisle, waved her arms, and opened her mouth to yell, when a hand yanked her under a rotted bench.

Agatha tackled her in a hug. “I found the School Master’s tower! It’s in the moat and there’s guards, but if we can just get up there then we can—”

“Hi! Nice to see you! Give me your clothes,” said Sophie, staring at Agatha’s pink dress.

“Huh?”

“Quick! It will solve everything.”

“You can’t be serious! Sophie, we can’t stay here!”

“Exactly,” Sophie smiled. “I need to be in your school and you need to be in mine. Just like we talked about, remember?”

“But your father, my mother, my cat!” Agatha sputtered. “You don’t know what they’re like here! They’ll turn us into snakes or squirrels or shrubbery! Sophie, we have to get back home!”

“Why? What do I have in Gavaldon to go back to?” Sophie said.

Agatha blushed with hurt. “You have . . . um, you have . . .”

“Right. Nothing. Now, my dress, please.”

Agatha folded her arms.

“Then I’ll take it myself,” Sophie scowled. But right as she grabbed Agatha by her flowered sleeve, something made her stop cold. Sophie listened, ears piqued, and took off like a panther. She slid under warped benches, dodged villains’ feet, ducked behind the last pew, and peeked around it.

Agatha followed, exasperated. “I don’t know what’s gotten into yo—”

Sophie covered Agatha’s mouth and listened to the sounds grow louder. Sounds that made every Good girl bolt upright. Sounds they had waited their whole lives to hear. From the hall, the stomp of boots, the clash of steel—

The west doors flew open to sixty gorgeous boys in swordfight.

Sun-kissed skin peeked through light blue sleeves and stiff collars; tall navy boots matched high-cut waistcoats and knotted slim ties, each embroidered with a single gold initial. As the boys playfully crossed blades, their shirts came untucked from tight beige breeches, revealing slender waists and flashes of muscle. Sweat glistened on glowing faces as they thrust down the aisle, boots cracking on marble, until swiftly the swordfight climaxed, boys pinning boys against pews. In a last chorus of movement, they drew roses from their shirts and with a shout of “Milady!” threw them to the girls who most caught their eye. (Beatrix found herself with enough roses to plant a garden.)

Agatha watched all this, seasick. But then she saw Sophie, heart in throat, longing for her own rose.

In the decayed pews, the villains booed the princes, brandishing banners with “NEVERS RULE!” and “EVERS STINK!” (Except for weasel-faced Hort, who crossed his arms sulkily and mumbled, “Why do they get their own entrance?”) With a bow, the princes blew kisses to villains and prepared to take their seats when the west doors suddenly slammed open again—

And one more walked in.

Hair a halo of celestial gold, eyes blue as a cloudless sky, skin the color of hot desert sand, he glistened with a noble sheen, as if his blood ran purer than the rest. The stranger took one look at the frowning, sword-armed boys, pulled his own sword . . . and grinned.

Forty boys came at him at once, but he disarmed each with lightning speed. The swords of his classmates piled up beneath his feet as he flicked them away without inflicting a scratch. Sophie gaped, bewitched. Agatha hoped he’d impale himself. But no such luck, for the boy dismissed each new challenge as quickly as it came, the embroidered T on his blue tie glinting with each dance of his blade. And when the last had been left swordless and dumbstruck, he sheathed his own sword and shrugged, as if to say he meant nothing by it at all. But the boys of Good knew what it meant. The princes now had a king. (Even the villains couldn’t find reason to boo.)

Meanwhile, the Good girls had long learned that every true princess finds a prince, so no need to fight each other. But they forgot all this when the golden boy pulled a rose from his shirt. All of them jumped up, waving kerchiefs, jostling like geese at a feeding. The boy smiled and lofted his rose high in the air—

Agatha saw Sophie move too late. She ran after her but Sophie dashed into the aisle, leapt over the pink pews, lunged for the rose—and caught a wolf instead.

As it dragged Sophie back to her side, she locked eyes with the boy, who took in her fair face, then her horrid black robes and cocked his head, baffled. Then he saw Agatha agog in pink, his rose plopped in her open palm, and recoiled in shock. As the wolf dumped Sophie with Evil and fairies shoved Agatha with Good, the boy gawked wide-eyed, trying to make sense of it all. Then a hand pulled him into a seat.

“Hi. I’m Beatrix,” she said, and made sure he saw all of her roses.

From the Evil seats, Sophie tried to get his attention.

“Turn yourself into a mirror. Then you’ll have a chance.”

Sophie turned to Hester, sitting next to her.

“His name is Tedros,” her roommate said. “And he’s just as stuck-up as his father.”

Sophie was about to ask who his father was, but then glimpsed his sword, dazzling silver, with a hilt of diamonds. A sword with a lion crest she knew from storybooks. A sword named Excalibur.

“He’s King Arthur’s son?” Sophie breathed. She studied Tedros’ high cheekbones, silky blond hair, and thick, tender lips. His broad shoulders and strong arms filled out his blue shirt, tie loosened and collar undone. He looked so serene and assured, as if he knew destiny was on his side.

Gazing at him, Sophie felt her own destiny lock into place.

He’s mine.

Suddenly she felt a hot glare across the aisle.

“We’re going home,” Agatha mouthed clearly.

“Welcome to the School for Good and Evil,” said the nicer of the two heads.

From their seats on opposite sides of the aisle, Sophie and Agatha tracked the massive dog with two heads attached to a single body, pacing across a silver stone stage, cracked down the middle. One head was rabid, drooling, and male, with a grizzly mane. The other head was cuddly and cute, with a weak jaw, scanty fur, and singsong voice. No one was sure if the cuter head was male or female, but whatever it was, it seemed to be in charge.

“I’m Pollux, Welcoming Leader,” said the nice head.

“AND I’M CASTOR, WELCOMING LEADER ASSISTANT AND EXECUTIVE EXECUTIONER OF PUNISHMENT FOR ANYONE WHO BREAKS RULES OR ACTS LIKE A DONKEY,” the rabid one boomed.

All the children looked scared of Castor. Even the villains.

“Thank you, Castor,” said Pollux. “So let me first remind you why it is you’re here. All children are born with souls that are either Good or Evil. Some souls are purer than others—”

“AND SOME SOULS ARE CRAP!” Castor barked.

“As I was saying,” said Pollux, “some souls are purer than others, but all souls are fundamentally Good or Evil. Those who are Evil cannot make their souls Good, and those who are Good cannot make their souls Evil—”

“SO JUST ’CAUSE GOOD IS WINNING EVERYTHING DOESN’T MEAN YOU CAN SWITCH SIDES,” snarled Castor.

The Good students cheered, “EVERS! EVERS!”; Evil students retorted, “NEVERS! NEVERS!” before wolves doused Evers with water buckets, fairies cast rainbows over the Nevers, and both sides shut up.

“Once again,” said Pollux tightly, “those who are Evil cannot be good and those who are Good cannot be Evil, no matter how much you’re persuaded or punished. Now sometimes you may feel the stirrings of both but this just means your family tree has branches where Good and Evil have toxically mixed. But here at the School for Good and Evil, we will rid you of stirrings, we will rid you of confusion, we will try to make you as pure as possible—”

“AND IF YOU FAIL, THEN SOMETHING SO BAD WILL HAPPEN TO YOU THAT I CAN’T SAY, BUT IT INVOLVES YOU NEVER BEING SEEN AGAIN!”

“One more and it’s the muzzle!” Pollux yelled. Castor stared at his toes.

“None of these brilliant students will fail, I’m sure,” Pollux smiled at the relieved children.

“You say that every time and then someone fails,” Castor mumbled.

Sophie remembered Bane’s scared face on the wall and shuddered. She had to get to Good soon.

“Every child in the Endless Woods dreams of being picked to attend our school. But the School Master chose you,” said Pollux, scanning both sides. “For he looked into your hearts and saw something very rare. Pure Good and Pure Evil.”

“If we’re so pure, then what’s that?”

An impish blond boy with spiky ears stood from Evil and pointed to Sophie.

A burly boy from Good pointed to Agatha. “We have one too!”

“Ours smells like flowers!” yelled a villain.

“Ours ate a fairy!”

“Ours smiles too much!”

“Ours farted in our face!”

Sophie turned to Agatha, aghast.

“Every class, we bring two Readers here from the Woods Beyond,” Pollux declared. “They may know our world from pictures and books, but they know our rules just as well as you. They have the same talents and goals, the same potential for glory. And they too have been some of our finest students.”

“Like two hundred years ago,” Castor snorted.

“They are no different than the rest of you,” Pollux said defensively.

“They look different than the rest of us,” cracked an oily, brown-skinned villain.

Students from both schools murmured in agreement. Sophie stared down Agatha, as if to say this could all be solved with a simple costume change.

“Do not question the School Master’s selections,” said Pollux. “All of you will respect each other, whether you’re Good or Evil, whether you’re from a famous tale family or a failed one, whether you’re a sired prince or a Reader. All of you are chosen to protect the balance between Good and Evil. For once that balance is compromised . . .” His face darkened. “Our world will perish.”

A hush fell over the hall. Agatha grimaced. The last thing she needed was this world perishing while they were still in it.

Castor raised his paw. “What,” Pollux groaned.

“Why doesn’t Evil win anymore?”

Pollux looked like he was about to bite his head off, but it was too late. The villains were rumbling.

“Yeah, if we’re so balanced,” yelled Hort, “why do we always die?”

“We never get good weapons!” shouted the impish boy.

“Our henchmen betray us!”

“Our Nemesis always has an army!”

Hester stood. “Evil hasn’t won in two hundred years!”

Castor tried to control himself, but his red face swelled like a balloon. “GOOD IS CHEATING!”

Nevers leapt up in mutiny, hurling food, shoes, and anything else at hand at horrified Evers—

Sophie slunk down in her seat. Tedros couldn’t possibly think she was one of these ugly hooligans, could he? She peeked over the bench and caught him staring right at her. Sophie pinked and ducked back down.

Wolves and fairies pounced on the angry horde around her, but this time rainbows and water couldn’t stop them.

“The School Master’s on their side!” Hester screamed.

“We don’t even have a chance!” howled Hort.

The Nevers fought past fairies and wolves, and charged the Evers’ pews—

“It’s because you’re idiotic apes!”

The villains looked up dumbly.

“Now sit down before I give all of you a slap!” shrieked Pollux.

They sat without argument. (Except Anadil’s rats, who peeked from her pocket and hissed.)

Pollux scowled down at the villains. “Maybe if you stopped complaining, you’d produce someone of consequence! But all we hear is excuse after excuse. Have you produced one decent villain since the Great War? One villain capable of defeating their Nemesis? No wonder Readers come here confused! No wonder they want to be Good!”

Sophie saw kids on both sides of the aisle sneak her sympathetic glances.

“Students, all of you have only one concern here,” Pollux said, softening. “Do the best work you can. The finest of you will become princes and warlocks, knights and witches, queens and sorcerers—”

“OR A TROLL OR PIG IF YOU STINK!” Castor spat.

Students glanced at each other across the aisle, sensing the high stakes.

“So if there are no further interruptions,” Pollux said, glowering at his brother, “let’s review the rules.”

“Rule thirteen. Halfway Bridge and tower roofs are forbidden to students,” Pollux lectured onstage. “The gargoyles have orders to kill intruders on sight and have yet to grasp the difference between students and intruders—”

Sophie found all of this dull, so she tuned out and stared at Tedros instead. She had never seen a boy so clean. Boys in Gavaldon smelled like hogs and slopped around with chapped lips, yellow teeth, and black nails. But Tedros had heavenly tan skin, dabbed with light stubble, and no hint (no chance!) of a blemish. Even after the vigorous swordfight, every last gold hair fell in place. When he licked his lips, white teeth gleamed through in perfect rows. Sophie watched a trickle of sweat crisscross his neck and vanish beneath his shirt. What does he smell like? She closed her eyes. Like fresh wood and—

She opened her eyes and saw Beatrix subtly sniffing Tedros’ hair.

This girl needed to be dealt with immediately.

A headless bird landed in Sophie’s dress. She jumped on her seat, screaming and shaking her tunic until the dead canary plopped to the floor. She recognized the bird with a frown—then noticed the entire hall gaping at her. She gave her best princess curtsy and sat back down.

“As I was saying,” Pollux said testily.

Sophie whipped to Agatha. “What!” she mouthed.

“We need to meet,” Agatha mouthed back.

“My clothes,” Sophie mouthed, and turned back to the stage.

Hester and Anadil looked at the decapitated bird, then at Agatha.

“Her we like,” Anadil quipped, rats squeaking in agreement.

“Your first year will consist of required courses to prepare you for three major tests: the Trial by Tale, the Circus of Talents, and the Snow Ball,” Castor growled. “After the first year, you will be divided into three tracks: one for villain and hero Leaders, one for henchmen and helper Followers, and one for Mogrifs, or those that will undergo transformation.”

“For the next two years, Leaders will train to fight their future Nemeses,” Pollux said. “Followers will develop skills to defend their future Leaders. Mogrifs will learn to adapt to their new forms and survive in the treacherous Woods. Finally, after the third year, Leaders will be paired with Followers and Mogrifs and you will all move into the Endless Woods to begin your journeys . . .”

Sophie tried to pay attention but couldn’t with Beatrix practically in Tedros’ lap. Fuming, Sophie picked at the glittering silver swan crest stitched on her smelly smock. It was the only tolerable thing about it.

“Now as to how we determine your future tracks, we do not give ‘marks’ here at the School for Good and Evil,” said Pollux. “Instead, for every test or challenge, you will be ranked within your classes so you know exactly where you stand. There are 120 students in each school and we have divided you into six groups of 20 for your classes. After each challenge, you will be ranked from 1 to 20. If you are ranked in the top five in your group consistently, you will end up on the Leader track. If you score in the midrange repeatedly, you’ll end up a Follower. And if you’re consistently below a 13, then your talents will be best served as a Mogrif, either animal or plant.”