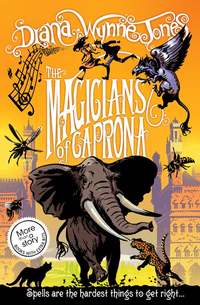

The Magicians of Caprona

The long golden villas on the hillside below the Palace each had a leaf-green or cherry-red disc on their walls. Some were half hidden by the dark spires of the elegant little trees planted in front of them, but Tonino knew they were there. And the stone and metal arches of the New Bridge, sweeping away from him towards the villas and the Palace, each bore an enamel plaque, green and red alternately. The New Bridge had been sustained by the strongest spells the Casa Montana and the Casa Petrocchi could produce.

At the moment, when the river was just a shingly trickle, they did not seem necessary. But in winter, when the rain fell in the Apennines, the Voltava became a furious torrent. The arches of the New Bridge barely cleared it. The Old Bridge – which Tonino could see by craning out and sideways – was often under water, and the funny little houses along it could not be used. Only Montana and Petrocchi spells deep in its foundations stopped the Old Bridge being swept away.

Tonino had heard Old Niccolo say that the New Bridge spells had taken the entire efforts of the entire Montana family. Old Niccolo had helped make them when he was the same age as Tonino. Tonino could not have done. Miserable, he looked down at the golden walls and red pantiles of Caprona below. He was quite certain that every single one hid at least a leaf-green scrip. And the most Tonino had ever done was help stamp the winged horse on the outside. He was fairly sure that was all he ever would do.

He had a feeling somebody was calling him. Tonino looked round at the Piazza Nuova. Nobody. Despite the view, the Piazza was too far for the tourists to come. All Tonino could see were the mighty iron griffins which reared up at intervals all round the parapet, reaching iron paws to the sky. More griffins tangled into a fighting heap in the centre of the square to make a fountain. And even here, Tonino could not get away from his family. A little metal plate was set into the stone beneath the huge iron claws of the nearest griffin. It was leaf-green. Tonino found he had burst into tears.

Among his tears, he thought for a moment that one of the more distant griffins had left its stone perch and come trotting round the parapet towards him. It had left its wings behind, or else had them tightly folded. He was told, a little smugly, that cats do not need wings. Benvenuto sat down on the parapet beside him, staring accusingly.

Tonino had always been thoroughly in awe of Benvenuto. He stretched out a hand to him timidly. “Hallo, Benvenuto.”

Benvenuto ignored the hand. It was covered with water from Tonino’s eyes, he said, and it made a cat wonder why Tonino was being so silly.

“There are our spells everywhere,” Tonino explained. “And I’ll never be abley—Do you think it’s because I’m half English?”

Benvenuto was not sure quite what difference that made. All it meant, as far as he could see, was that Paolo had blue eyes like a Siamese and Rosa had white fur—

“Fair hair,” said Tonino.

—and Tonino himself had tabby hair, like the pale stripes in a tabby, Benvenuto continued, unperturbed. And those were all cats, weren’t they?

“But I’m so stupid—” Tonino began.

Benvenuto interrupted that he had heard Tonino chattering with those kittens yesterday, and he had thought Tonino was a good deal cleverer than they were. And before Tonino went and objected that those were only kittens, wasn’t Tonino only a kitten himself?

At this, Tonino laughed and dried his hand on his trousers. When he held the hand out to Benvenuto again, Benvenuto rose up, very high on all four paws, and advanced to it, purring. Tonino ventured to stroke him. Benvenuto walked round and round, arched and purring, like the smallest and friendliest kitten in the Casa. Tonino found himself grinning with pride and pleasure. He could tell from the waving of Benvenuto’s brush of a tail, in majestic, angry twitches, that Benvenuto did not altogether like being stroked – which made it all the more of an honour.

That was better, Benvenuto said. He minced up to Tonino’s bare legs and installed himself across them, like a brown muscular mat. Tonino went on stroking him. Prickles came out of one end of the mat and treadled painfully at Tonino’s thighs. Benvenuto continued to purr. Would Tonino look at it this way, he wondered, that they were both, boy and cat, a part of the most famous Casa in Caprona, which in turn was part of the most special of all the Italian States?

“I know that,” said Tonino. “It’s because I think it’s wonderful too that I—Are we really so special?”

Of course, purred Benvenuto. And if Tonino were to lean out and look across at the Cathedral, he would see why.

Obediently, Tonino leaned and looked. The huge marble bubbles of the Cathedral domes leapt up from among the houses at the end of the Corso. He knew there never was such a building as that. It floated, high and white and gold and green. And on the top of the highest dome the sun flashed on the great golden figure of the Angel, poised there with spread wings, holding in one hand a golden scroll. It seemed to bless all Caprona.

That Angel, Benvenuto informed him, was there as a sign that Caprona would be safe as long as everyone sang the tune of the Angel of Caprona. The Angel had brought that song in a scroll straight from Heaven to the First Duke of Caprona, and its power had banished the White Devil and made Caprona great. The White Devil had been prowling round Caprona ever since, trying to get back into the city, but as long as the Angel’s song was sung, it would never succeed.

“I know that,” said Tonino. “We sing the Angel every day at school.” That brought back the main part of his misery. “They keep making me learn the story – and all sorts of things – and I can’t, because I know them already, so I can’t learn properly.”

Benvenuto stopped purring. He quivered, because Tonino’s fingers had caught in one of the many lumps of matted fur in his coat. Still quivering, he demanded rather sourly why it hadn’t occurred to Tonino to tell them at school that he knew these things.

“Sorry!” Tonino hurriedly moved his fingers. “But,” he explained, “they keep saying you have to do them this way, or you’ll never learn properly.”

Well, it was up to Tonino of course, Benvenuto said, still irritable, but there seemed no point in learning things twice. A cat wouldn’t stand for it. And it was about time they were getting back to the Casa.

Tonino sighed. “I suppose so. They’ll be worried.”

He gathered Benvenuto into his arms and stood up.

Benvenuto liked that. He purred. And it had nothing to do with the Montanas being worried. The aunts would be cooking lunch, and Tonino would find it easier than Benvenuto to nick a nice piece of veal.

That made Tonino laugh. As he started down the steps to the New Bridge, he said, “You know, Benvenuto, you’d be a lot more comfortable if you let me get those lumps out of your coat and comb you a bit.”

Benvenuto stated that anyone trying to comb him would get raked with every claw he possessed.

“A brush then?”

Benvenuto said he would consider that.

It was here that Lucia encountered them. She had looked for Tonino all over Caprona by then and she was prepared to be extremely angry. But the sight of Benvenuto’s evil lop-sided countenance staring at her out of Tonino’s arms left her with almost nothing to say. “We’ll be late for lunch,” she said.

“No we won’t,” said Tonino. “We’ll be in time for you to stand guard while I steal Benvenuto some veal.”

“Trust Benvenuto to have it all worked out,” said Lucia. “What is this? The start of a profitable relationship?”

You could put it that way, Benvenuto told Tonino. “You could put it that way,” Tonino said to Lucia.

At all events, Lucia was sufficiently impressed to engage Aunt Gina in conversation while Tonino got Benvenuto his veal. And everyone was too pleased to see Tonino safely back to mind too much. Corinna and Rosa minded, however, that afternoon, when Corinna lost her scissors and Rosa her hairbrush. Both of them stormed out on to the gallery. Paolo was there, watching Tonino gently and carefully snip the mats out of Benvenuto’s coat. The hairbrush lay beside Tonino, full of brown fur.

“And you can really understand everything he says?” Paolo was saying.

“I can understand all the cats,” said Tonino. “Don’t move, Benvenuto. This one’s right on your skin.”

It says volumes for Benvenuto’s status – and therefore for Tonino’s – that neither Rosa nor Corinna dared say a word to him. They turned on Paolo instead. “What do you mean, Paolo, standing there letting him mess that brush up? Why couldn’t you make him use the kitchen scissors?”

Paolo did not mind. He was too relieved that he was not going to have to learn to understand cats himself. He would not have known how to begin.

From that time forward, Benvenuto regarded himself as Tonino’s special cat. It made a difference to both of them. Benvenuto, what with constant brushing – for Rosa bought Tonino a special hairbrush for him – and almost as constant supplies filched from under Aunt Gina’s nose, soon began to look younger and sleeker. Tonino forgot he had ever been unhappy. He was now a proud and special person. When Old Niccolo needed Benvenuto, he had to ask Tonino first. Benvenuto flatly refused to do anything for anyone without Tonino’s permission. Paolo was very amused at how angry Old Niccolo got.

“That cat has just taken advantage of me!” he stormed. “I ask him to do me a kindness and what do I get? Ingratitude!”

In the end, Tonino had to tell Benvenuto that he was to consider himself at Old Niccolo’s service while Tonino was at school. Otherwise Benvenuto simply disappeared for the day. But he always, unfailingly, reappeared around half-past three, and sat on the water butt nearest the gate, waiting for Tonino. And as soon as Tonino came through the gate, Benvenuto would jump into his arms.

This was true even at the times when Benvenuto was not available to anyone. That was mostly at full moon, when the lady cats wauled enticingly from the roofs of Caprona.

Tonino went to school on Monday, having considered Benvenuto’s advice. And, when the time came when they gave him a picture of a cat and said the shapes under it went: Ker-a-ter, Tonino gathered up his courage and whispered, “Yes. It’s a C and an A and a T. I know how to read.”

His teacher, who was new to Caprona, did not know what to make of him, and called the Headmistress. “Oh,” she was told. “It’s another Montana. I should have warned you. They all know how to read. Most of them know Latin too – they use it a lot in their spells – and some of them know English as well. You’ll find they’re about average with sums, though.”

So Tonino was given a proper book while the other children learnt their letters. It was too easy for him. He finished it in ten minutes and had to be given another. And that was how he discovered about books. To Tonino, reading a book soon became an enchantment above any spell. He could never get enough of it. He ransacked the Casa Montana and the Public Library, and he spent all his pocket money on books. It soon became well known that the best present you could give Tonino was a book – and the best book would be about the unimaginable situation where there were no spells. For Tonino preferred fantasy. In his favourite books, people had wild adventures with no magic to help or hinder them.

Benvenuto thoroughly approved. While Tonino read, he kept still, and a cat could be comfortable sitting on him. Paolo teased Tonino a little about being such a bookworm, but he did not really mind. He knew he could always persuade Tonino to leave his book if he really wanted him.

Antonio was worried. He worried about everything. He was afraid Tonino was not getting enough exercise. But everyone else in the Casa said this was nonsense. They were proud of Tonino. He was as studious as Corinna, they said, and, no doubt, both of them would end up at Caprona University, like Great-Uncle Umberto. The Montanas always had someone at the University. It meant they were not selfishly keeping the Theory of Magic to the family, and it was also very useful to have access to the spells in the University Library.

Despite these hopes for him, Tonino continued to be slow at learning spells and not particularly quick at school. Paolo was twice as quick at both. But as the years went by, both of them accepted it. It did not worry them. What worried them far more was their gradual discovery that things were not altogether well in the Casa Montana, nor in Caprona either.

CHAPTER THREE

It was Benvenuto who first worried Tonino. Despite all the care Tonino gave him, he became steadily thinner and more ragged again. Now Benvenuto was roughly the same age as Tonino. Tonino knew that was old for a cat, and at first he assumed that Benvenuto was just feeling his years. Then he noticed that Old Niccolo had taken to looking almost as worried as Antonio, and that Uncle Umberto called on him from the University almost every day. Each time he did, Old Niccolo or Aunt Francesca would ask for Benvenuto and Benvenuto would come back tired out. So he asked Benvenuto what was wrong.

Benvenuto’s reply was that they might let a cat have some peace, even if the Duke was a booby. And he was not going to be pestered by Tonino into the bargain.

Tonino consulted Paolo, and found Paolo worried too. Paolo had been noticing his mother. Her fair hair had lately become several shades paler with all the white in it, and she looked nervous all the time. When Paolo asked Elizabeth what was the matter, she said, “Oh nothing, Paolo – only all this makes it so difficult to find a husband for Rosa.”

Rosa was now eighteen. The entire Casa was busy discussing a husband for her, and there did, now Paolo noticed, seem much more fuss and anxiety about the matter than there had been over Cousin Claudia, three years before. Montanas had to be careful who they married. It stood to reason. They had to marry someone who had some talent at least for spells or music; and it had to be someone the rest of the family liked; and, above all, it had to be someone with no kind of connection with the Petrocchis. But Cousin Claudia had found and married Arturo without all the discussion and worry that was going on over Rosa. Paolo could only suppose the reason was “all this”, whatever Elizabeth had meant by that.

Whatever the reason, argument raged. Anxious Antonio talked of going to England and consulting someone called Chrestomanci about it. “We want a really strong spell-maker for her,” he said. To which Elizabeth replied that Rosa was Italian and should marry an Italian. The rest of the family agreed, except that they said the Italian must be from Caprona. So the question was who.

Paolo, Lucia and Tonino had no doubt. They wanted Rosa to marry their cousin Rinaldo. It seemed to them entirely fitting. Rosa was lovely, Rinaldo handsome, and none of the usual objections could possibly be made. There were two snags, however. The first was that Rinaldo showed no interest in Rosa. He was at present desperately in love with a real English girl – her name was Jane Smith, and Rinaldo had some difficulty pronouncing it – and she had come to copy some of the pictures in the Art Gallery down on the Corso. She was a romantic girl. To please her, Rinaldo had taken to wearing black, with a red scarf at his neck, like a bandit. He was said to be considering growing a bandit moustache too. All of which left him with no time for a cousin he had known all his life.

The other snag was Rosa herself. She had never cared for Rinaldo. And she seemed to be the only person in the Casa who was entirely unconcerned about who she would marry. When the argument raged loudest, she would shake the blonde hair on her shoulders and smile. “To listen to you all,” she said, “anyone would think I have no say in the matter at all. It’s really funny.”

All that autumn, the worry in the Casa Montana grew. Paolo and Tonino asked Aunt Maria what it was all about. Aunt Maria at first said that they were too young to understand. Then, since she had moments when she was as passionate as Aunt Gina or even Aunt Francesca, she told them suddenly and fervently that Caprona was going to the dogs.

“Everything’s going wrong for us,” she said. “Money’s short, tourists don’t come here, and we get weaker every year. Here are Florence, Pisa and Siena all gathering round like vultures, and each year one of them gets a few more square miles of Caprona. If this goes on we shan’t be a State any more. And on top of it all, the harvest failed this year. It’s all the fault of those degenerate Petrocchis, I tell you! Their spells don’t work any more. We Montanas can’t hold Caprona up on our own! And the Petrocchis don’t even try! They just keep turning things out in the same old way, and going from bad to worse. You can see they are, or that child wouldn’t have been able to turn her father green!”

This was disturbing enough. And it seemed to be plain fact. All the years Paolo and Tonino had been at school, they had grown used to hearing that there had been this concession to Florence; that Pisa had demanded that agreement over fishing rights; or that Siena had raised taxes on imports to Caprona. They had grown too used to it to notice. But now it all seemed ominous. And worse shortly followed. News came that the Old Bridge had been seriously cracked by the winter floods.

This news caused the Casa Montana real dismay. For that bridge should have held. If it gave, it meant that the Montana charms in the foundations had given too. Aunt Francesca ran shrieking into the yard. “Those degenerate Petrocchis! They can’t even sustain an old spell now! We’ve been betrayed!”

Though no one else put it quite that way, Aunt Francesca probably spoke for the whole family.

As if that was not enough, Rinaldo set off that evening to visit his English girl, and was led back to the Casa streaming with blood, supported by his cousins Carlo and Giovanni. Rinaldo, using curse words Paolo and Tonino had never heard before, was understood to say he had met some Petrocchis. He had called them degenerate. And it was Aunt Maria’s turn to rush shrieking through the yard, shouting dire things about the Petrocchis. Rinaldo was the apple of Aunt Maria’s eye.

Rinaldo had been bandaged and put to bed, when Antonio and Uncle Lorenzo came back from viewing the damage to the Old Bridge. Both looked very serious. Old Guido Petrocchi himself had been there, with the Duke’s contractor, Mr Andretti. Some very deep charms had given. It was going to take the whole of both families, working in shifts, at least three weeks to mend them.

“We could have used Rinaldo’s help,” Antonio said.

Rinaldo swore that he was well enough to get out of bed and help the next day, but Aunt Maria would not hear of it. Nor would the doctor. So the rest of the family was divided into shifts, and work went on day and night. Paolo, Lucia and Corinna went to the bridge straight from school every day. Tonino did not. He was still too slow to be much use. But from what Paolo told him, he did not think he was missing much. Paolo simply could not keep up with the furious pace of the spells. He was put to running errands, like poor Cousin Domenico. Tonino felt very sympathetic towards Domenico. He was the opposite of his dashing brother Rinaldo in every way, and he could not keep up with the pace of things either.

Work had been going on, often in pouring rain, for nearly a week, when the Duke of Caprona summoned Old Niccolo to speak to him.

Old Niccolo stood in the yard and tore what was left of his hair. Tonino laid down his book (it was called Machines of Death and quite fascinating) and went to see if he could help.

“Ah, Tonino,” said Old Niccolo, looking at him with the face of a grieving baby. “I have gigantic problems. Everyone is needed on the Old Bridge, and that ass Rinaldo is lying in bed, and I have to go before the Duke with some of my family. The Petrocchis have been summoned too. We cannot appear less than they are, after all. Oh why did Rinaldo choose such a time to shout stupid insults?”

Tonino had no idea what to say, so he said, “Shall I get Benvenuto?”

“No, no,” said Old Niccolo, more upset than ever. “The Duchess cannot abide cats. Benvenuto is no use here. I shall have to take those who are no use on the bridge. You shall go, Tonino, and Paolo and Domenico, and I shall take your uncle Umberto to look wise and weighty. Perhaps that way we shan’t look so very thin.”

This was perhaps not the most flattering of invitations, but Tonino and Paolo were delighted nevertheless. They were delighted even though it rained hard the next day, the drilling white rain of winter. The dawn shift came in from the Old Bridge under shiny umbrellas, damp and disgruntled. Instead of resting, they had to turn to and get the party ready for the Palace.

The Montana family coach was dragged from the coach-house to a spot under the gallery, where it was carefully dusted. It was a great black thing with glass windows and monster black wheels. The Montana winged horse was emblazoned in a green shield on its heavy doors. The rain continued to pour down. Paolo, who hated rain as much as the cats did, was glad the coach was real. The horses were not. They were four white cardboard cut-outs of horses, which were kept leaning against the wall of the coach-house. They were an economical idea of Old Niccolo’s father’s. As he said, real horses ate and needed exercise and took up space the family could live in. The coachman was another cardboard cut-out – for much the same reasons – but he was kept inside the coach.

The boys were longing to watch the cardboard figures being brought to life, but they were snatched indoors by their mother. Elizabeth’s hair was soaking from her shift on the bridge and she was yawning until her jaw creaked, but this did not prevent her doing a very thorough scrubbing, combing and dressing job on Paolo and Tonino. By the time they came down into the yard again, each with his hair scraped wet to his head and wearing uncomfortable broad white collars above their stiff Eton jackets, the spell was done. The spell-streamers had been carefully wound into the harness, and the coachman clothed in a paper coat covered with spells on the inside. Four glossy white horses were stamping as they were backed into their traces. The coachman was sitting on the box adjusting his leaf-green hat.

“Splendid!” said Old Niccolo, bustling out. He looked approvingly from the boys to the coach. “Get in, boys. Get in, Domenico. We have to pick up Umberto from the University.”

Tonino said goodbye to Benvenuto and climbed into the coach. It smelt of mould, in spite of the dusting. He was glad his grandfather was so cheerful. In fact everyone seemed to be. The family cheered as the coach rumbled to the gateway, and Old Niccolo smiled and waved back. Perhaps, Tonino thought, something good was going to come from this visit to the Duke, and no one would be so worried after this.

The journey in the coach was splendid. Tonino had never felt so grand before. The coach rumbled and swayed. The hooves of the horses clattered over the cobbles just as if they were real, and people hurried respectfully out of their way. The coachman was as good as spells could make him. Though puddles dimpled along every street, the coach was hardly splashed when they drew up at the University, with loud shouts of “Whoa there!”

Uncle Umberto climbed in, wearing his red and gold Master’s gown, as cheerful as Old Niccolo. “Morning, Tonino,” he said to Paolo. “How’s your cat? Morning,” he said to Domenico. “I hear the Petrocchis beat you up.” Domenico, who would have died sooner than insult even a Petrocchi, went redder than Uncle Umberto’s gown and swallowed noisily. But Uncle Umberto never could remember which younger Montana was which. He was too learned. He looked at Tonino as if he was wondering who he was, and turned to Old Niccolo.