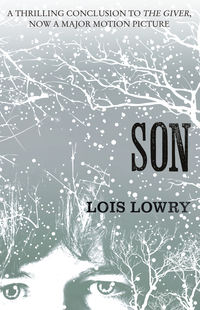

Son

Now she would be working here, at the Hatchery. And living here too, she assumed, at least until … until when? Citizens were given dwellings when they were assigned spouses. Birthmothers never had spouses, so she had not thought about it until now. Now she wondered. Was she eligible now for a spouse, and eventually for—? Claire sighed. It was troubling, and confusing, to think about such things. She turned away from the holding ponds, made her way to the front door of the main building, and was met there by Dimitri.

* * *

That night, alone in the small bedroom she’d been assigned, Claire looked down from her window to the darkened, surging river below. She yawned. It had been a long and exhausting day. This morning she had awakened in her familiar surroundings, the place where she had lived for so many months, but by midday her entire life had shifted. She had not had a chance to say goodbye to her friends, the other Vessels. They would be wondering where she had gone, but would likely forget her soon. She had taken her place here, been issued a nametag, and been introduced to the other workers. They seemed pleasant enough. Some, older than Claire, had spouses and dwellings, and left at the end of the day’s work. Others, like herself, lived here, in rooms along the corridor. One, Heather, had been the same year as Claire; she had been a Twelve at the same ceremony. Surely she would remember Claire’s Assignment as Birthmother. Her eyes flickered in recognition when they were introduced, but Heather said nothing. Neither did Claire. There was nothing really to say.

She supposed that she and the younger workers, including Heather, would become friends, of a sort. They would sit together at meals and go in groups to attend community entertainments. After a while they would have shared jokes, probably things about fish, phrases that would make them chuckle. It had been that way with the other Vessels, and Claire found herself missing, already, the easy camaraderie among them. But she would fit in here. Everyone welcomed her cheerfully and said they’d be glad of her help.

The work wouldn’t be hard. She had been allowed to watch the lab attendants, in gowns and gloves, strip eggs from what they called the breeder fish, anesthetized females. A little like squeezing toothpaste, she thought, amused at the image. Nearby, other attendants squeezed what they told her was “milt” from the male; then they added the creamy substance to the container that held the fresh eggs. It had to be very precisely timed, they explained. And antiseptic. They worried about contamination, and bacteria. The temperature made a difference as well. Everything was carefully controlled.

In a nearby room lit by dim red lights, she had watched another gloved worker look through trays of stacked fertilized eggs.

“See those spots?” the worker had asked Claire. She pointed to the tray of glistening pink eggs. Claire peered down and saw that most of them had two dark spots. She nodded.

“Eyes,” the girl told her.

“Oh,” Claire said, amazed that already, so young and tiny that she could hardly think of it as a fish, it had eyes.

“See here?” Using a metal tool, the girl pointed to a discolored, eyeless egg. “This one’s dead.” Carefully she plucked it from the tray with her forceps and discarded it in the sink. Then she returned the tray to its rack and reached for the next one.

“Why did it die?” Claire asked. She found that she was whispering. The room was so dimly lit, so quiet and cool, that her voice was hushed.

But the worker replied in a normal tone, very matter-of-fact. “I don’t know. The insemination went wrong, I guess.” She shrugged and removed another dead egg from the second tray. “We have to take them out so they don’t contaminate the good ones. I check them every day.”

Claire felt a vague discomfort. The insemination had gone wrong. Was that what had happened to her? Had her Product, like the discolored, eyeless egg, been thrown aside someplace? But no. They had told her that number Thirty-six was “fine.” She tried to set aside her troubling thoughts and pay attention to the worker’s voice and explanations.

“Claire?” The door opened and it was Dimitri, the supervisor, looking for her. “I want to show you the dining room. And they have your schedule almost ready to give you.”

So she had continued her tour of the facility, and been instructed in her next day’s duties (cleaning, mostly—everything had to be kept spotless), and later she had had supper with a group of the workers who lived, as she would now, at the Hatchery. They talked, mostly, about what they had done during recreation time. There was an hour allotted each day when they could do whatever they liked. Someone mentioned a bike ride and a picnic lunch along the river; apparently the kitchen staff would pack your lunch in a basket if you asked in advance. Two young men had joined a ball game. Someone had watched repairs being done on the bridge. It was aimless, pleasant chat, but it served to remind Claire that she was freer now than she had been in a long time. She could go for a walk after lunch, she thought, or in the evening.

Later, in her room, thinking, she realized what she wanted to do when she had time. Not just an ordinary walk. She wanted to try to find a girl named Sophia, a girl her own age, a girl who had turned twelve when Claire did. They had not been particular friends, just acquaintances and schoolmates who had happened to share a birth year. But Sophia had been seated next to Claire at the ceremony when they were given their Assignments.

“Birthmother,” the Chief Elder had announced when it was Claire’s turn to stand and be acknowledged. She had shaken the Chief Elder’s hand, smiled politely at the audience, taken her official Assignment papers, and gone back to her seat. Sophia had stood, next.

“Nurturer,” the Chief Elder had named Sophia.

It had meant little to Claire, then. But now it meant that Sophia, an assistant at first, probably by now fully trained, was working in the Nurturing Center, the place where Claire’s Product—her child, her baby—was being held, and fed.

* * *

Days passed. Claire waited for the right time. Usually the workers took their breaks in pairs or groups. People would wonder if she wandered off alone during a break; there would be murmurs about her, and questions. She didn’t want that. She needed them to see her as hard-working and responsible, as someone ordinary, someone without secrets.

So she waited, worked, and began to fit in. She made friends. One lunchtime she joined several coworkers in a picnic along the riverbank. They leaned their bikes against nearby trees and sat on some flat rocks in the high grass while they unpacked the prepared food. Nearby, on the path, two young boys rode by on their bikes, laughing at something, and waved to them.

“Hey, look!” One boy was pointing. “Supply boat!”

Eagerly the two youngsters dropped their bikes and scrambled down the sloping riverbank to watch as the bargelike boat passed, its open deck heavy with wooden containers of various sizes.

Rolf, one of the picnickers, looked at his watch and then at the boys. “They’re going to be late getting back to school,” he commented with a wry smile.

The others all chuckled. Now that they were finished with school, it was easy to be amused by the regulations that they had all lived by as children. “I was late once,” Claire told them, “because a groundskeeper sliced his hand when he was pruning the bushes over by the central offices. I stopped and watched while they bandaged him and took him off to the infirmary for stitches.

“I used to hope I’d be assigned Nursing Attendant,” she added.

There was an awkward silence for a moment. Claire wasn’t certain if they knew her background. Undoubtedly there had been some explanation given for her sudden appearance at the Hatchery, but probably they had been told no details. To have failed at one’s Assignment—to be reassigned—had something of a shame to it. No one would ever mention it, if they did know. No one would ask.

“Well, the committee knows best,” Edith commented primly as she passed sandwiches around. “Anyway, there’s an element of nursing at the Hatchery. All the labs and procedures.”

Claire nodded.

“Hatchery wouldn’t have been my first choice,” a tall young man named Eric said. “I was really hoping for Law and Justice.”

“My brother’s there,” Claire told him.

“Does he like it?” Eric asked with interest.

Claire shrugged. “I guess so. I never see him. He was older. Once he finished his training, he moved away from our dwelling. He might even have a spouse by now.”

“You’d know that,” Rolf pointed out. “You see the Spouse Assignments at the Ceremony.

“I’ve applied for a spouse,” he added, grinning. “I had to fill out about a thousand forms.”

Claire didn’t tell them that she had not attended the last two ceremonies. Birthmothers did not leave their quarters during their years of production. Claire had never seen a Vessel until she became one. She had not known, until she had both experienced and observed it, that human females swelled and grew and reproduced. No one had told her what “birth” meant.

“Look!” Eric said suddenly. “The supply boat’s stopping at the Hatchery. Good! I put in an order quite a while ago.” He glanced down at the riverbank, where the two youngsters were still watching the boat. “Boys!” he called. When they looked up, he pointed to the watch on his own wrist. “The school bell is going to ring in less than five minutes!”

Reluctantly they climbed back up the bank and went to retrieve their bikes. “Thank you for the reminder,” one said politely to Eric.

“You think the supply boat will still be there after school?” the other boy asked eagerly.

But Eric shook his head. “They unload quickly,” he told the boy, who looked disappointed.

“I wish I could be a boat worker,” they could hear one boy say to the other as they set their bikes upright. “I bet they go lots of places we don’t even know about. I bet if I were working on a supply boat, I’d get to see—”

“If we don’t get back on time,” his friend said nervously, “we’re not going to be assigned anything! Come on, let’s get going!”

The boys rode away toward the school building in the distance.

“I wonder what he thought he’d get to see, as a boat worker,” Rolf commented. They began to tidy up the picnic and to pack away the uneaten food.

“Other places. Other communities. The boats must make a lot of stops.” Eric folded the napkins and placed them in the basket.

“They’d all be the same. What’s so exciting about seeing a different hatchery, a different school, a different nurturing center, a different—”

Edith interrupted them. “It’s pointless to speculate,” she said in her terse, businesslike tone. “Accomplishes nothing. ‘Wondering’ is very likely against the rules, though I suppose it isn’t a serious infringement.”

Eric rolled his eyes and handed Rolf the basket. “Here,” he said. “Strap this on your bike and take it back, would you? I have to do an errand. I told the lab chief that I’d pick up some stuff at the Supply Center.”

Rolf, attaching the basket to his bike by its transportation straps, commented, “It might be nice to travel on the river, though, just for the trip. Fun to see new things. Even,” he added facetiously, “if you haven’t wondered about them.”

Edith ignored that.

“Could be dangerous,” Eric pointed out. “That water’s deep.” He looked around, making sure they had collected everything. “Ready to go back?” Claire and Edith nodded and moved their bikes to the path. Eric waved and rode off on his errand.

Even if it might be against the rules, some kind of infringement (it would be hard to know without studying the thick book of community regulations, though it was always available on the monitor in the Hatchery lobby, but there were pages and pages of very small print, and no one ever bothered to look at it, as far as Claire could tell), there would be no way for anyone to get caught in the act of wondering, Claire thought. It was an invisible thing, like a secret. She herself spent a great deal of time at it … wondering.

Pedaling back, she rehearsed in her mind, silently, how easy it would be to say in a casual voice, “I have to run an errand.” How she could slip away—it wouldn’t take long—and ride over to the Nurturing Center, to find Sophia and ask some questions.

THEN THE OCCASION came.

“I just realized that the biology teacher never returned the posters I let him use,” Dimitri said irritably at lunch. “And I’ll need them tomorrow morning.”

“I’ll go get them,” Claire offered.

“Thanks.” The lab director nodded in her direction. “That’s a help. There will be a group of volunteers starting indoctrination, and the visual aids make things easier.”

They were eating in the Hatchery cafeteria, six of them at the same table. There was no assigned seating, and today Claire, balancing her tray of prepared food, had made her way to an empty chair at this table where the director was already sitting with several technicians. He was talking about a set of demonstration posters that he liked to use when there were visitors being given a tour of the facility. The biology teacher had borrowed them and they had not yet been returned.

“Notify the school. They’ll have a student bring them.” One of the technicians had finished eating and was tidying his tray. “And they’ll chastise the teacher,” he added, with a malicious chuckle, as he stood.

“No need,” Claire said. “I have another errand over that way. It’ll be easy for me to stop by the school.” That wasn’t really a lie, she told herself. Lying was against the rules. They all knew that, abided by it. And she hadn’t made it up, the other errand she had mentioned. She only hoped no one would ask her what it was. But their attention was elsewhere now. They were crumpling their napkins, looking at their watches, preparing to return to work.

It was her chance to look for Sophia.

* * *

Her stop at the school was brief, and the biology teacher didn’t recognize her. Claire had never studied biology. At twelve, when the selections were made and the future jobs assigned, the children’s education took different paths. Some in her group—she remembered a boy named Marcus, who excelled in school and was assigned a future as an engineer—would continue on and learn various sciences. He had probably completed biology by now, she guessed, and would be studying higher mathematics, or astrophysics, or biochemistry, one of the subjects that was whispered about, when they were young, as incomprehensibly difficult. Marcus wouldn’t be in this ordinary school anymore, but in one of the higher education buildings reserved for scholars.

Though she had been young at the time, Claire remembered when Peter, her brother, had moved on to higher education. Maybe Peter had even learned biology in school. But then he had been transferred over to the law buildings, for his clerkship and studies.

The hallways were familiar, and she found the biology classroom without difficulty.

“I had intended to return these,” the biology teacher told her, handing Claire the rolled-up posters. “Would you please tell him that I didn’t realize he would need them back so soon?” He sounded slightly annoyed.

“Yes, I’ll tell him. Thank you.” Claire left the teacher there at his desk in the classroom and made her way down the hall toward the front door. She glanced into the empty rooms. School hours had ended and the children had gone to their various volunteer jobs in the community. But she was familiar with some of the rooms, and she recognized a language teacher who leaned over a desk, packing things into a briefcase. Claire nodded uncertainly when the woman looked up and saw her.

“Claire, is it?” The teacher smiled. “What a surprise! What—”

But she didn’t continue the question, though the look on her face was curious. Certainly the teacher would have remembered her selection as Birthmother, and clearly a Birthmother had no business in the school, or in fact anywhere in the day-to-day geography of the community. But it would have been extremely rude to ask why Claire was there. So the teacher cut off her own question and simply smiled in greeting.

“I’m just here collecting something,” Claire explained, holding up the cylinder of posters. “It’s nice to see you again.”

She continued down the hall and out through the front entrance of the education building, and took her bicycle from the rack by the steps. Carefully she attached the bundle of papers securely to the holder on the back of the bike. Nearby, a gardener transplanting a bush glanced at her without interest. Two children on bicycles pedaled past quickly, rushing toward something, probably worried about being late for their required volunteer hours.

Everything was familiar, unchanged, but it still felt odd to Claire to be back in the community again. She had not ventured far from the Hatchery before this, just the short excursions with her coworkers. Over there, she thought, looking down the path she had ridden to get to the school, I can almost see the dwelling where I grew up.

Briefly she wondered about her parents, whether they ever thought of her—or, for that matter, of Peter. They had raised two children successfully, fulfilling the job of Adults with Spouses. Peter had achieved a highly prestigious Assignment. And she, Claire, had not. Birthmother. At the ceremony, standing on the stage to receive her Assignment, she had not been able to see her parents’ faces in the crowd. But she could imagine how they looked, how disappointed they would have been. They had hoped for more from their female child.

“There’s honor in it,” she remembered her mother saying reassuringly that night. “Birthmothers provide our future population.”

But it felt a little like those times when they had opened the dinner delivery containers to find that the evening meal would be grains prepared with fish oil. “High vitamin D,” her mother would say in that same cheerful voice, in an attempt to make the meal seem more appealing than it really was.

Claire biked away from the education buildings and hesitated at the corner, where several paths intersected. She could turn right and ride past the back of Law and Justice, straight along that path, and be back at the Hatchery in a few minutes. But instead, she continued straight, then turned left, so that the House of the Old, surrounded by trees, was just ahead of her. She turned right here and slowed her bicycle near the Childcare Center, steering carefully around a food delivery vehicle being unloaded. Then she made her way straight ahead toward the Nurturing Center.

It was surprising, she thought, as she approached the structure, that she had never spent volunteer hours there as a schoolgirl. She had worked often at the Childcare Center, and had enjoyed the time playing educational games with the toddlers and young children, but infants—they were called newchildren—had never interested her. Some of her friends and age-mates had thought the little ones “cute.” But not Claire. From what she had heard described, they were endless work—feeding, rocking, bathing—and they cried too much. She had avoided doing her hours there.

Now, planning how she would present herself at the entrance to the Nurturing Center, Claire realized that she was excited, and a little nervous. She rehearsed what she might say when she went inside. To ask for Sophia would be foolish. Sophia would probably barely remember her; they had not been particular friends. But why else would she be appearing there, asking to enter?

Well, Claire decided abruptly, she would lie once again. Against the rules. She knew that. Once, she would have cared. Now she didn’t. As simple as that. And it was just a small lie.

She wheeled her bicycle into the rack where several slots had been left open for visitors. Then she disengaged the rolled posters from the carrier and took them with her to the front door. Inside, a young woman sitting at a desk looked up from her papers and smiled at her. “Good afternoon,” she said politely, peering at Claire’s nametag. “Can I help you?”

Claire introduced herself. “I’m a worker at the Hatchery,” she explained. “We have these extra posters explaining the life cycle of salmon. I was wondering if you could use some to decorate your walls.”

If the young woman said yes, she realized, she would have some explaining to do to the Hatchery director, who was at this very moment expecting his posters back. But it was a pretty safe assumption that the answer would be no. Who would care about examining the growth of fish? It wasn’t even that interesting to those who worked with them.

And, indeed, the young woman smiled and shook her head. “Thank you,” she said, “but we have specially designed equipment to engage the attention of newchildren. We don’t deviate from the standard means of helping them to focus their attention span and to exercise their small muscles. Everything’s pretty carefully calibrated by the experts in infant development.”

Claire nodded. “Interesting,” she said. “I’m sorry I never volunteered here. I don’t know much about nurturing at all. Do you ever let visitors have a tour?”

The receptionist appeared pleased at her interest. “Never been here at all? My goodness! It’s such a fun place! You should certainly take a look, since you’re here anyway! Let me see who’s on duty.” She ran her finger down a list of names.

“Is Sophia here?” Claire asked. “She was with my age group.”

“Oh, Sophia! She’s such a diligent worker. Let me look. Yes—there’s her name. Let’s see if she’s available.”

Summoned through the intercom by the receptionist, Sophia entered the front hallway from a corridor on the side. She hadn’t changed much since they had both been twelve almost three years before. She was thin, with her hair pulled back under a cap, which seemed to be part of her uniform. Claire smiled at her. “Hi,” she said. “I don’t know if you remember me. I was a Twelve when you were. My name’s Claire.”

Sophia looked at Claire’s nametag and nodded with a small smile of recognition, after a moment. “We don’t wear nametags,” Sophia explained, “because the newchildren would grab at them. But I remember you. I think we were in the same math class.”

“I hated math. I was never very good at it.” Claire made a face.

Sophia chuckled. “I did pretty well, but it never interested me much. Remember Marcus? He got such high marks in math! He’s in engineering studies now.”

Claire nodded. “He was always studying,” she recalled.

Sophia frowned and peered toward the small print under Claire’s name on her nametag. “I forget what your Assignment was,” she said. “Your uniform is …”

“Fish Hatchery,” Claire explained quickly. Good. Sophia didn’t remember that she had been assigned Birthmother.

“And so what are you doing here?”

“Hoping to get a tour!” Claire told her. “Somehow I missed out on the whole Nurturing section. And I have a little free time this afternoon.”

“Oh. Well, all right. You can follow along and I’ll explain things. But I have to work. It’s almost feeding time. Come on. Clean your hands first.” Sophia pointed to a disinfectant dispenser on the wall of the corridor, and Claire followed her example, rubbing her hands carefully with the clear medicinal liquid.

“The youngest ones are in this first room.” Youngest ones. That meant the most recent newchildren. Claire thought back, and remembered which of her sister Vessels had been preparing to give birth when she was dismissed. These would be their Products.

“We can’t go in this one without changing to sterile uniforms. But we can look at them.” Sophia pointed through a window to a spotlessly clean area filled with small wheeled carts, many empty. Two workers, a young man in a nurturer’s uniform and a volunteer, a girl of ten or so, were tidying things. They looked up at the window, saw the two observers, and smiled.