The Sons of Scarlatti

Screens came online.

World leaders started to appear.

FIVE

“Mr President.”

“Commander King.”

“Prime Minister.”

“King. Mr President.”

“Prime Minister.”

“Guten Tag, Frau Chancellor…”

King went through the introductory motions.

Finn thought, I’m supposed to be in double geography right now.

The President of the USA was in shirtsleeves – the Oval Office in the background familiar, if a little less tidy than in its TV incarnations. The British Prime Minister was in a large, book-lined room – not the smooth PM of news bulletins, but an alarmed posh little man. The German Chancellor settled herself into a reclaimed pine ‘ergonomische stuhl’ as the President of France came online from the gilt and ornate Élysée Palace.

“Is Allenby there?” said the US President.

Al leant into shot and waved so that the leaders of the free world could see him.

“Guys,” said Al.

Guys? Finn thought.

“So. What have we got, Commander King?” asked Al.

The room fell silent. The lights dimmed.

“Slide,” ordered King.

A digital projection lit up a wall-sized screen and showed… nothing.

Or at least nothing but a blank whiteness with a black dot in the middle.

King snapped, “Bring it up to scale.”

The lens zoomed in on the dot and suddenly the creature exploded across the screen.

Projected to the size of a man, a vile black, yellow and red-flecked monster, fresh and newborn-slick from its final moult. Its exoskeleton was extended, exaggerated; its thorax like a clutch of girders; its head a felt and fang atrocity; its silver-black wings still plastered against its abdomen which, cruelly coloured, scaled and distended, hung bulbous from its thorax like a great droplet of buzz-fresh poison. And, at its end, an ugly cluster of three barbed, glossy harpoon stings.

Finn froze and the hairs on the back of his neck prickled. For a moment he tasted his own fear. The fear of death he sometimes got when he thought about his mother. A sense of something terrible, unstoppable and unknowable. He gulped it back.

A mouse click and the next image flashed up. A rear shot of the insect with a better view of the array of stings emerging from the bulbous abdomen.

Click. The underside, amour-plated and beetle-black. How does this thing fly? Finn thought.

Click. In the next image, the answer: silver-black wings fully extended, as long as a dragonfly’s, but broader.

Wow.

Click. The head and mouthparts, feelers and proboscis. Finn felt his stomach turn. He didn’t want to look, yet couldn’t tear his eyes away.

Click. The egg pouch and reproductive organ.

The six legs.

The black and yellow and red-tinged whole, like some vile bullet that in flight must look like… Who only knew what.

And the sound? thought Finn. What evil bass buzz would those wings make?

Al watched, face frozen, King pleasantly surprised to observe that even he was stilled by the sight.

“Meet Scarlatti,” said King. “Named after the eighteenth-century Italian composer noted for writing five hundred and fifty-five piano sonatas, because it registers a score of five hundred and fifty-five on the Porton Scale: that used to measure the lethal potential of weaponised organisms. A single Scarlatti could theoretically kill five hundred and fifty-five human beings.”

“Sacré bleu…” said the French President, without a hint of irony.

“During the Cold War, all sides developed and produced biological weapons. One of the main branches of study at our research institute at Porton Down was entomology, the study of insects, and how they could be adapted to carry and spread disease. In 1983 a geneticist accidentally developed a whole new genotype of insect by exposing the embryo of a highly engineered smallpox-carrying wasp – phenotype Vespula cruoris – to gamma radiation. The result was… Scarlatti.”

An old video recording came up onscreen of live Scarlattis being studied in a laboratory.

“Scarlatti is an asexual self-multiplier that, given a sufficient supply of simple protein – the body of a dead mammal say – can lay up to fifty eggs. It’s pesticide resistant, seventy-five millimetres long (the size of a hummingbird or a human thumb) and is all but physically indestructible. It nurtures supplies of a unique and fatal strain of smallpox in the poison sacs of its abdomen. Accelerated development means a single egg can become a viable flying insect in four days. Therefore a single insect can produce a fifty-strong swarm in four days. And swarm they do – given how much protein is required during their nymph, or rapid hemimetabolic, phase. Each swarm produces many new colonies, each swarming every four days, and so on ad infinitum. Or until the supply of protein dries up.”

Finn could taste something sickening.

He means people by ‘the supply of protein’. He means… us.

Onscreen, the video turned nasty. White mice were introduced to the test chamber and seized upon by frenzied Scarlattis. They seemed to relish the kill, whipping their stings into the poor creatures long after they were disabled or dead.

“This hideous project was immediately discontinued, the remaining nymphs first being frozen and then incinerated at the end of the Cold War under the Biological Weapons Convention.

“However, two specimens remained. One was sent to the United States under the Hixton-Fardale Shared Research Agreement, and has presumably been destroyed.. A second was secretly frozen and stored at Porton Down by the government of the day ‘just in case’ or, as we like to put it more formally, for ‘Reasons of National Security’.”

Commander King allowed his eyelids to close so as to avoid the righteous glares of the other committee members. Then he took a deep breath.

“One of our Porton Down research fellows, a Dr Cooper-Hastings, seems to have lost all reason, found a way to access the secure cold store and… has released the last remaining Scarlatti.”

There were gasps.

“He did what?” asked the US President.

King turned to his screen. “Dr Cooper-Hastings released the specimen into the atmosphere, sir.”

A staff-card mugshot of a middle-aged scientist flashed up. Thick glasses. Dull eyes.

“He stayed late at work, leaving at 10pm. A search was initiated six minutes later when an algorithm discovered an access control code override on his staff card. An empty cryogenic support cylinder was eventually found outside his abandoned car at 03:32 this morning near the village of Hazelbrook, thirty-six miles north of here.”

A map of Hazelbrook flashed up onscreen and a photo of the abandoned car.

“The area around the village has been declared a biohazard zone and evacuated. We’re conducting a full investigation and every available officer from every agency is involved in the manhunt for Cooper-Hastings.”

“Cut to the chase. What exactly are we talking about here – worst case?” asked the US President.

King and Professor Channing exchanged looks. The Professor stood up to deliver the bad news.

“Worst case: we estimate that with a first swarm in four days national contamination will be total within four to six weeks, continental within three months, global-temperate within six months.”

“Global-temperate?” repeated the US President.

“Nearly all of Western Europe, a good two-thirds of North America, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, most of South America, Australia. Only cold air and altitude offer any protection. In total, two-thirds of the land mass of the earth.”

There was a pause.

“Nearly six billion people,” said King.

DAY ONE 13:38 (BST). English Channel

Dr Miles Cooper-Hastings opened his eyes. They stung. Blackness and stars swam before him. His throat was so dry he half retched to bring forth some saliva. He could see nothing, but he could feel his head pressed up against something wooden. He was freezing. For a waking moment of pure terror, he wondered if he was buried alive. But, as his body repulsed and kicked out at these thoughts, the lid of the sea chest he had been locked in for eight hours or so leapt up as far as its lock and clasp would allow and for a split second let in a strip of daylight.

He kicked out again. He saw light flash again. And he realised he could taste the freezing sea.

“Where is it?” Cooper-Hastings yelled into the blackness, fear filling his lungs. “What have you done?”

SIX

“On day one the Scarlatti lays its eggs,” said King. “On day two the nymphs hatch and grow. On day three the nymphs develop distinct body sections and the wings separate – shedding their skin several times. By the start of day four – after their final moult – they can swarm.”

The danger was spelt out in a fan graph that showed a range of possible development outcomes if the Scarlatti had located a ‘host protein’ overnight. The blood-red line of development started tight on day one and by day four spread to cover the entire graph.

“Four days. We’re already halfway through day one and we daren’t risk day four,” said King.

He turned away from the graph and back to his guests.

“So far, so bad. What matters is what we do now,” he said.

There was an air of stunned disbelief in the control gallery and around the world.

Seated beside the US President, General Jackman – the grizzly bear Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the world’s most powerful soldier – punctured the silence:

“Create hell. Flood the area with chemicals. Go nuclear.”

“Thank you, General Jackman. The problem is – scale,” explained King.

On a projected map he drew a rough semicircle east of the village of Hazelbrook.

“Last night’s turbulent air could have taken it twenty miles north and east, which means an area that covers roughly a third of London.”

“Nuke London…?” said someone, appalled.

“Or,” King said before a hubbub could break out, “following on from discussions with the scientists this morning, there may be another way.”

With a quick glance at Al, King turned to the corner of the gallery.

“Entomologists, would you oblige us?”

Channing beckoned a pair of entomologists from Porton Down into camera view, part of the group that had been there since early morning. A grey, middle-aged man with a much younger, sharper colleague.

“Professor Lomax and Dr Spiro were colleagues of Dr Cooper-Hastings at Porton Down.”

Lomax wore a suit under his lab coat, Spiro a T-shirt and jeans.

“Professor Channing? The hypothesis, please.”

Finn remembered his mum explaining that hypothesis was a term scientists used to describe an idea so they didn’t sound common.

“Pheromones,” Channing began, pushing back his glasses as if addressing a learned symposium, “are tiny distinct chemical signals that all living things emit.”

“‘Phero’ from the Greek for ‘to carry’,” Professor Lomax helpfully explained, “‘mone’ from ‘hormone’ or—”

Dr Spiro cut across them with the urgency the occasion demanded.

“If we can trace the Scarlatti’s pheromones then we can catch it before its first swarm. We could locate it, find its nest and destroy a much, much smaller area.”

“Possibly,” interjected Lomax, glaring. But Spiro continued.

“The ’83 data is categorical. Scarlatti pheromones are very distinct – the result of atomic mutation almost certainly – and emitted in very large quantities, with receptor sensitivity heightened by a super-developed swarm instinct. These insects will do anything to be with their own kind. Anything.”

“Thank you, Dr Spiro, I did produce much of that data…” muttered Lomax.

But how? How would you trace the pheromones? Finn wanted to yell, wriggling in his hidey-hole and finding it difficult to keep his mouth shut. King sensed it and shot an eyebrow his way.

“How?” asked Al obligingly. “How would you begin to define and then detect the appropriate molecules, let alone—”

“With another member of the same species!” Professor Channing announced, striking a blow for the over-fifties by jumping in before young Dr Spiro.

Al looked across at Finn. He raised his eyebrows at him: “Plausible?”

Finn shrugged back a Why not?

“Non!” said the French Conseiller Scientifique. “You would have to replicate Scarlatti. If Scarlatti is a random atomic mutation, you could never replicate it exactement. Never. C’est impossible!”

“Unless, of course, there is still a second sample left in existence?” mused Commander King, letting the cynical words hang in the air.

“Ach, the American one?” said the German Chancellor. “Destroyed, nein?”

“Like we destroyed ours?” said the British Prime Minister.

All eyes turned to the US President.

“Retained for ‘Reasons of National Security’ you mean?” said Commander King, enjoying the moment. “Where would it be, I wonder? The Fort Detrick facility outside Washington? One might look in warehouse nine, aisle eight, section two S.”

“Find out,” the President snapped at someone off-screen, furious that King should so easily reel off a US state secret. General Jackman bristled.

“Forget it. Even if it is there,” said the US Chief Scientist, a silver-haired woman on the President’s other side, “you’d never be able to get a viable tracking device on to something that small.”

King smiled. Inside.

“Any thoughts? Dr Allenby?”

Al pushed himself out of his seat and walked over to the giant image of the Scarlatti, deep in thought. He turned back to Spiro. “You’re sure they’ll read each other’s pheromones over great distances?”

“Over miles, definitely,” said Spiro.

“More than ten?”

“Reasonable probability,” said Spiro.

“Really…” Lomax sighed. “More than ‘reasonable’ at ten, unlikely beyond twenty.”

“Can we anchor a tracking device on to that thorax?”

Spiro and Lomax looked puzzled.

Al changed tack.

“Theoretically, if we could drill into it, or glue it on to, say, this cross member here?” He pointed out a girder-like section of the armoured thorax that flattened at the centre.

“Theoretically? Yes,” said Spiro. “This is cellulose material without nerve endings.”

“You would have to ‘theoretically’ be extremely careful then,” said Lomax, attempting sarcasm. “The thorax plates move against each other to allow greater flexibility than in other wasp species. It’s a weak point so the joints between the plates are packed with nerve endings.”

Al checked his watch, a Rolex adapted to his own design to incorporate a Geiger counter, pressure gauge and half a dozen other tiny instruments (the secret gift from a grateful nation), and turned things over in his mind. Tick tick tick tick tick.

“Well, Allenby? Will you revisit Project Boldklub?” said the Prime Minister.

Most people in the meeting didn’t have a clue what he was talking about. The name Boldklub was obscure, being short for Akademisk Boldklub, the football club that Niels Bohr, the father of subatomic physics, once played for.

Al looked at King, suspicious. King studied his nails.

“We’ve faced down one chemical and two nuclear Armageddons in the recent past. I don’t see why we can’t pull together as a team to deal with this.”

King looked back up at Al.

The world waited. Al looked over at Finn.

And from his hiding place Finn studied the Scarlatti. The colours, the grotesque armour, the clutch of stings, the distorted feelers and proboscis… everything about it gave off a sense of anger and suffering. In a perverse way Finn felt sorry for it. Yet within a few months this thing could wipe out six billion people. Everyone he knew, as well as the four he loved (Grandma, Al, Yo-yo and sometimes Christabel), plus everyone that filled his day, from everyone he watched on telly to everyone he travelled to school with. All gone. Like his mum.

Finn was fascinated, locked on.

“Oh… go on then,” said Al at last.

“What? Go on what?” barked General Jackman from the US.

Al seemed to snap awake. “We haven’t got much time. I suppose I’d better explain.”

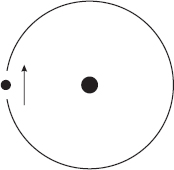

He picked up an iPad linked to an interactive whiteboard and started to draw.

SEVEN

Al looked up, as if to a classroom of kids.

“Anyone know what this is?”

“It’s an atom,” said General Mount, irritated by Al’s playful tone.

“Is this a physics class?” asked the American President.

“Yep. Everyone needs to get a handle on this. It is indeed an atom,” said Al. “Which one?”

Hydrogen! Finn wanted to say, itching to put his hand up.

“Hydrogen,” muttered the US Chief Scientist.

“Good, a hydrogen atom, nice and simple: a nucleus in the centre and one electron spinning around, with a constant spatial relationship between the nucleus and the electron – this distance, this distance right here.” Al drew a dotted red line between the dot at the centre and the dot on the outside.

He then tapped the two spots again, the nucleus and the electron. “Now these two dots are something, matter, stuff,” he explained, “but this –” he waved around inside the circle all over the place – “is absolutely nothing.”

“Me, you, everything around us is more than 99.9 per cent nothing, because every single one of the atoms we’re constructed from is more than 99.9 per cent nothing, with only a tiny bit of actual atomic stuff. Everyone got that?”

Al looked up at the world leaders, then glanced across at Finn, to make sure they were all still with him; with furrowed brows and a big grin respectively, they were.

“I will never understand this,” said the British Prime Minister.

“There’s a whole quantum dark energy/dark matter thing we could go into, but it’s better to think of it as a beautiful mystery. Think of atoms as being balloons rather than building blocks, balloons filled with nothingness and a tiny nucleus.”

“Bravo,” said the French President. “But this not catch flies.”

“Not yet, no. But my Big Idea, known to a select few as Boldklub, was –” he pointed again to the red dotted line denoting the distance between the nucleus and the electron – “to see if we could create a magnetic field that could reduce this distance and—”

And before Al could say the next word a neural synapse fired at the speed of light in Finn’s brain and a conclusion so fantastic occurred it smashed any last compunction to stay quiet.

“You’re going to SHRINK stuff?”

Everyone turned. Finn’s eyes were as wide as wonder.

Lit from below by the iPad, and looking 99.9 per cent mad scientist, Al pointed straight at him. “Ta-da!”

“WHAT?”

“What did he say?”

“Shrink stuff?”

“C’est impossible!”

“Mein Gott, was that a child?”

Commander King let his eyelids drop in momentary exasperation. This really was all he needed.

“That’s my nephew,” said Al proudly.

“Young Infinity is here contingent upon Dr Allenby’s cooperation,” King declared. “We really must move on…”

Heads were shaking, voices rising, English, American, French, German – all demanding answers, all offended by such an absurd suggestion, at being caught out by a child.

Finn didn’t give a damn. He was staring at Al in open-mouthed wonder.

“Shrink? Is that really what the boy said?”

“This is flat out impossible,” the US Chief Scientist advised her President.

Al overheard. “No! Possible –” he insisted, adding a much smaller atom to his diagram – “by exploiting a chain reaction at the quantum level, you can create a new type of magnetic field, a ‘hot area’ within which all matter can be reduced, sucking the electron right up tight against the nucleus.”

“That is totally absurd!” the US Chief Scientist responded.

Voices immediately started to rise again.

The entomologists were stunned.

Finn’s mind was spinning. He wanted to ask a million questions. He wanted to understand every impossible detail. He wanted to know about the who and the why and the how. He wanted to know it all and yet somehow, right now, it was all so much to try and take in and he was just thinking: I Want A Go.

He walked straight up to his uncle through the babble, looked into his eyes and asked in wonder and for a second time, just to make sure, “You’re going to shrink stuff. You’re going to shrink some soldiers and get this thing?”

“Yes I am,” said Al, delighted with Finn, who then all but burst with questions.

“Won’t you still be the same weight when you’re tiny as when you’re full size?”

“No, because there’s a proportionate shrinking of dark matter…”

“Will you be really dense and super tough?”

“Theoretically, no, though of course power-to-mass ratios are different and gravity won’t break you so easily…”

“Will bacteria and diseases be able to eat you, like, really easily, like flesh-eating bugs chewing off your face and arms and ears and nose and— Hey! Will you be able to smell?”

“The rule of thumb for nano-to-normal interaction at the molecular level is that complex compounds don’t interact, though atoms and simple molecules do, so you can relax about contracting the Ebola virus…”

They were having to raise their voices as the meeting was all but out of control, until the chilling opening bars of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ emerged from Al’s jacket.

It was the ringtone he had assigned to one very special caller. For the first time, Al looked scared. He checked the time again – nearly two o’clock – and began to panic.

“Shush! Shut uuuuuup! SHUT UP!” he shouted at the room.

The room gradually fell silent as everyone looked at Al, frozen in terror. Once again Finn got there before everyone else.

“Grandma!”

“Is his Grossmutti there too?” the German Chancellor asked.

“Nobody say a word!” insisted Al.

The leaders of the free world, along with their best and brightest, followed orders and “shut up” as Al interrupted The Phantom and took the call.

“Hey! Mum! How’s Oslo? I know I promised, I’m sorry, I lost track of time… No, don’t call the police, we’re fine! That’s ridiculous… Have you transferred to the ship?”

With his outstretched arm, he indicated that everyone could relax a little; he had the situation under control.

“He’s fine, he’s right here, he can tell you himself… oh, school? School’s clo— canteen! No! School canteen’s closed, they were sent home for lunch – no food. Wasp infestation. Astonishing… No, he’s fine! Here…” He put his hand over the mouthpiece and handed it to Finn, whispering, “Speak! Just tell her everything’s fine.”