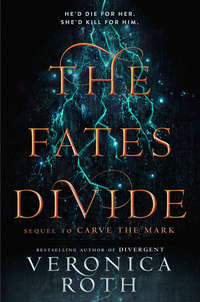

The Fates Divide

“Miss Kereseth,” he says, without looking at me. “You look so much like the elder of your two brothers.” He glances at me, then, appraising. “Are you not curious what’s become of him?”

I want to answer coolly, like Ryzek is nothing to me. I want to meet his eyes with strength. I want a thousand fantasies of revenge to come suddenly to life like hushflowers at the Blooming.

I open my mouth, but nothing comes out.

Fine, I think, and I let out a peal of my currentgift, like a clap of my hands. I’ve come to understand that not everybody can control their currentgifts the way I can. I just wish I could master the part that keeps me from saying what I want to.

I see how he relaxes when my gift hits him. It has no effect on Isae—none that I can see, anyway—but maybe it will loosen his tongue. And whatever Isae is planning, she seems to need him to talk first.

“My father, the great Lazmet Noavek, taught me that people can be like blades, if you learn to wield them, but your best weapon should still be yourself,” Ryzek says. “I have always taken that to heart. Some of the kills I have commanded have been carried out by others, Chancellor, but rest assured, those deaths are still mine.”

He slumps forward over his knees, clasping his hands between them. He and Isae are just breaths apart.

“I will mark your sister’s life on my arm,” he says. “It will be a fine trophy to add to my collection.”

Ori. I remember which tea she drank in the morning (harva bark, for energy and clarity) and how much she hated the chip in her front tooth. And I hear the chants of the Shotet in my ears: Die, die, die.

“That clarifies things,” Isae says.

She holds her hand out for him to take. He gives her an odd look, and no wonder—what kind of person wants to shake hands with the man who just admitted to ordering her sister’s death? And being proud of it?

“You really are an odd one,” he says. “You must not have loved your sister very much, to offer your hand to me now.”

I see the skin pull taut over the knuckles of her other hand, the one not held out to him. She opens her fist, and inches her fingers toward her boot.

Ryzek takes the hand she offered, then stiffens, eyes widening.

“On the contrary, I loved her more than anyone,” Isae says. She squeezes him, hard, digging in her fingernails. And all the while, her left hand moves toward her boot.

I’m too stunned to realize what’s happening until it’s too late. With her left hand she tugs a knife out of her boot, from where it’s strapped to her leg. With her right, she pulls him forward. Knife and man come together, and she presses, and the sound of his gurgling moan carries me to my living room, to my adolescence, to the blood that I scrubbed from the floorboards as I sobbed.

Ryzek slumps, and bleeds.

I slam my hand down on the door handle and stumble into the hallway. I am wailing, crying, pounding on the walls; no, I’m not, my currentgift won’t let me.

All it allows me to do, in the end, is let out a single, weak scream.

I RAN TOWARD CISI Kereseth’s scream, Akos on my heels, not even bothering with the rungs of the ladder that took me below deck—I just jumped down. I went straight toward Ryzek’s cell, knowing, of course, that he was likely the source of anything that caused screaming on this ship. I saw Cisi braced against the corridor wall, the storage room door across from her open. Behind her, Teka dropped down from the other end of the ship, beckoned here by the same noise. Isae Benesit stood inside Ryzek’s cell, and below her, in a jumble of legs and arms, was my brother.

There was a certain amount of poetry in it, I supposed, that just as Akos had watched his father spill his life on the floor, so I now watched my brother do the same.

It took far longer for him to die than I anticipated. That was intentional, I assumed; Isae Benesit stood over his body the entire time, bloody knife in her fist, eyes blank but watchful. She had wanted to take her time with this moment, her moment of triumph over the one who killed her sister.

Well, one of the ones who killed her sister, because Eijeh, who had held the actual blade, was still in the next room.

Ryzek’s eyes found mine, and almost as if he’d touched me, I was buoyed into a memory. Not one that he was taking from me, but one I had almost hidden from myself.

I was in the passage behind the Weapons Hall, with my eye pressed to the crack in the wall panel. I had gone there to spy on my father’s meeting with a prominent Shotet businessman-turned-slumlord, because I often spied on my father’s meetings when I was bored and curious about the happenings of this house. But this meeting had gone bad, which had never happened before when I peeked in. My father had stretched out a hand, two fingers held aloft, like a Zoldan ascetic about to give a blessing, and the businessman had drawn his own knife, his movements jerky, like he was fighting his own muscles.

He brought the knife to the inside corner of his eye.

“Cyra!” hissed a voice behind me, making me jerk to attention. A young, spotted ryzek slid to his knees beside me. He cradled my face in his hands. I had not realized, before that moment, that I was crying. As the screaming started in the next room, he pressed his palms flat to my ears, and brought my face to his chest.

I struggled, at first, but he was too strong. All I could hear was the pounding of my own heart.

At last he pulled me away, wiped the tears from my cheeks, and said, “What does Mother always say? Those who go looking for pain …”

“Find it every time,” I replied, completing the phrase.

Teka held me by the shoulders, and jostled me a little, saying my name. I looked at her, then, confused.

“What is it?” I said.

“Your currentshadows were …” She shook her head. “Never mind.”

I knew what she meant. My currentgift had likely gone haywire, sending sprawling black lines all over me. The currentshadows had changed since Ryzek tried to use me to torture Akos in the cell block beneath the amphitheater. They drifted on top of my skin now, instead of burrowing beneath it like dark veins. But they were still painful, and I could tell this episode had been worse—my vision was blurry, and there were impressions of fingernails in my palms.

Akos was kneeling in my brother’s blood, his fingers on the side of Ryzek’s throat. I watched as his hand fell away, and he slumped, bracing himself on his thighs.

“It’s done,” Akos said, sounding thick, like his throat was coated in milk. “After everything Cyra did to help me—after everything—”

“I won’t apologize,” Isae said, finally looking away from Ryzek. She scanned all our faces—Akos, surrounded by blood; Teka, wide-eyed at my shoulder; me, arms streaked black; Cisi, holding her stomach near the wall. The air was pungent with the smell of sick.

“He murdered my sister,” Isae said. “He was a tyrant and a torturer and a killer. I won’t apologize.”

“It’s not about him. You think I didn’t want him dead?” Akos lurched to his feet. Blood ran down the front of his pants, from knees to ankles. “Of course I did! He took more from me than he did from you!” He was so close to her I wondered if he would lash out, but he made a fitful motion with his hands, and that was all. “I wanted him to fix what he did first, I wanted him to set Eijeh right, I …”

It seemed to hit him all at once. Ryzek was—had been—my brother, but the grief was his. He had persevered, carefully orchestrated every element of his brother’s rescue, only to find himself blocked, again and again, by people more powerful than he was. And now, he had succeeded in getting his brother out of Shotet, but he had not saved him, and all the planning, all the fighting, all the trying … was for nothing.

Akos fell against the nearest wall to hold himself up, closed his eyes, and swallowed a moan.

I found my way out of my trance.

“Go upstairs,” I said to Isae. “Take Cisi with you.”

She looked like she might object, for a moment, but it didn’t last. Instead, she dropped the murder weapon—a simple kitchen knife—right where she stood, and went to Cisi’s side.

“Teka,” I said. “Would you get Akos upstairs, please?”

“Are you—” Teka started, and stopped. “Okay.”

Isae and Cisi, Teka and Akos, they left me there, alone, with my brother’s body. He had died next to a mop and a bottle of disinfectant. How convenient, I thought, and stifled a laugh. Or tried to. But it wouldn’t stay stifled. In moments my knees were weak with laughter, and I fumbled through my hair for the side of my head that was now silverskin, to remind myself how he had sliced and diced me for the entertainment of a crowd, how he had planted pieces of himself inside me, as if I was just a barren field to sow with pain. My entire body carried the scars Ryzek Noavek had given me.

And now, at last, I was free of him.

When I calmed, I set about cleaning up Isae Benesit’s mess.

Ryzek’s body didn’t frighten me, and neither did blood. I dragged him by his legs into the hallway, sweat tickling the back of my neck as I heaved and pulled. He was heavy, in death, as I was sure he had been in life, skeletal though he was. When Akos’s oracle mother, Sifa, appeared to help me, I didn’t say anything to her, just watched as she worked a sheet beneath him so we could wrap him in it. She produced a needle and thread from the storage room, and helped me stitch the makeshift burial sack closed.

Shotet funerals, when they took place on land, involved fire, like most cultures in our varied solar system. But it was a special honor to die in space, on the sojourn. We covered the bodies, all but the head, so the loved ones of whoever was lost could see and accept the person’s death. When Sifa pulled the sheet back, away from Ryzek’s face, I knew she had at least studied our customs.

“I see so many possibilities for how things will unfold,” Sifa said finally, dragging her arm across her forehead to catch some of the sweat. “I didn’t think this one was likely, or I might have warned you.”

“No, you wouldn’t have,” I said, lifting a shoulder. “You only intervene when it suits your purposes. My comfort and ease don’t matter to you.”

“Cyra …”

“I don’t care,” I said. “I hated him. Just … don’t pretend that you care about me.”

“I am not pretending,” she replied.

I had thought, surely, that I might see some of Akos in her. And in her mannerisms, yes, perhaps he was there. Mobile eyebrows and quick, decisive hands. But her face, her light brown skin, her modest stature, they were not his.

I didn’t know how to evaluate her honesty, so I didn’t bother.

“Help me carry him to the trash chute,” I said.

I took the heavy side of his body, his head and shoulders, and she took his feet. It was lucky that the trash chute was only a few feet away, another unexpected convenience. We took it in stages, a few steps at a time. Ryzek’s head lolled around, his eyes open but sightless, but there was nothing I could do about it. I set him down next to the chute, and pressed the button to open the first set of doors, at waist height. It was fortunate that he was so narrow, or his shoulders wouldn’t have fit. Together Sifa and I folded him into the short channel, bending his legs so the inner doors would be able to close. Once they had, I pressed the button again, to open the outer doors and slide the tray in the chute forward to launch his body into space.

“I know the prayer, if you want me to say it,” Sifa said.

I shook my head.

“They said that prayer at my mother’s funeral,” I said. “No.”

“Then let us just acknowledge that he has suffered his fate,” Sifa said. “To fall to the family Benesit. He no longer needs to fear it.”

It was kind enough.

“I’m going to clean myself up,” I said. The blood on my palms was beginning to dry, making them itch.

“Before you do,” Sifa said, “I will warn you of this. Ryzek was not the only person the chancellor blamed for her sister’s death. In fact, she likely began with him because she was saving the more important piece of retribution for later. And she won’t stop there, either. I have seen enough of her to know her nature, and it is not forgiving.”

I blinked at her for a moment before it made sense to me. She was talking about Eijeh, still locked away in the other storage room. And not just Eijeh, but the rest of us—complicit, Isae believed, in Orieve’s death.

“There is an escape pod,” Sifa said. “We can put her in it, and someone from the Assembly will fetch her.”

“Tell Akos to drug her,” I said. “I don’t feel up to a fight right now.”

AKOS WADED THROUGH THE cutlery that was all over the galley floor. The water was already heating, and the vial of sedative was ready to dump into the tea, he just had to get some dried herbs into the strainer. The ship bumped along, and he stepped on a fork, flattening the tines with his heel.

He cursed his stupid head, which couldn’t stop telling him that there was still hope for Eijeh. There are so many people across the galaxy, with so many gifts. Somebody will know how to put him right. Truth was, Akos was tired of hanging on to hope. He’d been clawing at it since he first got to Shotet, and now he was ready to let go and just let fate take him where it wanted him to go. To death, and Noaveks, and Shotet.

All he’d promised his dad was that he would get Eijeh home. Maybe here—floating in space—was the best he could do. Maybe that would just have to be enough.

But—

“Shut up,” he said to himself, and he dumped the herbs from the galley cabinet into a strainer. There weren’t any iceflowers, but he’d learned enough about Shotet plants to make a simple calming blend. At this point, though, there was no artistry in it. He was just going through the motions, folding bits of garok root into powdered fenzu shell and squeezing a little nectar on top of it all, for taste. He didn’t even know what to call the plants that made up the nectar—he’d taken to calling the little fragile flowers “mushflowers” while he was at the army training camp outside Voa, because of how easily they fell apart, but he’d never learned the right name for them. They tasted sweet, and that seemed to be their only use.

When the water was hot, he poured it through the strainer. The extract it left behind was a murky brown, perfect for hiding the yellow of the sedative. His mom had told him to drug Isae and he hadn’t even asked why. He didn’t care, as long as it got her out of his sight. He couldn’t quite escape the image of her standing there watching Ryzek Noavek gush blood like it was some kind of show. Isae Benesit may have worn Ori’s face, but she wasn’t anything like her. He couldn’t imagine Ori just standing there and watching someone die, no matter how much she hated them.

Once the extract was brewed and mixed with the drug, he brought it to Cisi, who was sitting alone on the bench just outside the galley.

“You waiting for me?” he said.

“Yeah,” she said. “Mom told me to.”

“Good,” he said. “Will you take this to Isae? It’s just to calm her down.”

Cisi raised an eyebrow at him.

“Don’t drink any of it yourself,” he added.

She reached for it, but instead of taking the mug, she put her hand on his wrist. The look in her eyes changed—sharpened—like it always did when his currentgift dampened her own.

“What’s left of Eijeh?” she asked.

Akos’s whole body clenched up. He didn’t want to think about what was left of Eijeh.

“Someone who served Ryzek Noavek,” he said, with venom. “Who hated me, and Dad, and probably you and Mom, too.”

“How is that possible?” She frowned. “He can’t hate us just because someone put different memories into his head.”

“You think I know?” Akos all but growled.

“Then, maybe—”

“He held me down while someone tortured me.” Akos shoved the mug into her hands.

Some of the hot tea spilled on both their hands. Cisi jerked away, wiping her knuckles on her pants.

“Did I burn you?” he said, nodding to her hand.

“No,” she said. The softness her currentgift brought to her expression was back. Akos didn’t want tenderness of any kind, so he turned away.

“This won’t hurt her, will it?” Cisi said, tapping a fingernail on the mug so he would hear the ting ting ting.

“No,” he said. “It’s to keep from having to hurt her.”

“Then I’ll give it to her,” Cisi said.

Akos grunted a little. There was some more sedative in his pack, maybe he ought to take it. He’d never been so worn, like a half-finished weaving, light showing between all the threads. It would be easier just to sleep.

Instead of drugging himself to oblivion, though, he just took a dried hushflower petal from his pocket and stuck it between his cheek and his teeth. It wouldn’t knock him out, but it would dull him some. Better than nothing.

Akos was coasting on hushflower an hour later when Cisi came back.

“It’s done,” she said. “She’s out.”

“All right,” he said. “Then let’s get her into the escape pod.”

“I’m going with her,” Cisi said. “If Mom’s right, and we’re headed into war—”

“Mom’s right.”

“Yeah,” Cisi said. “Well, in that case, whoever’s against Isae is against Thuvhe. So I’m going to stick with my chancellor.”

Akos nodded.

“I take it you won’t be,” Cisi said.

“Fated traitor, remember?” he said.

“Akos.” She crouched in front of him. At some point he had sat down on the bench, which was hard and cold and smelled like disinfectant. Cisi rested an arm on his knee. She had tied her hair back, messy, and a chunk of curls had come loose, falling around her face. She was pretty, his sister, her face a shade of cool brown that reminded him of Trellan pottery. A lot like Cyra’s, and Eijeh’s, and Jorek’s. Familiar.

“You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to, just because Mom raised us fate-faithful and obedient to the oracles and all that,” Cisi said. “You’re a Thuvhesit. You should come with me. Leave everyone else to their war, and we’ll go home and wait it out. No one needs us here.”

He’d thought about it. He was as torn now as he’d ever been, and not just because of his fate. When he came out of the daze of the hushflower, he would remember how nice it felt to laugh with Cyra earlier that day, and how warm she was, pressed up against him. And he would remember that as much as he wanted to just be in his house again, walk up the creaky stairs and stoke the burnstones in the courtyard and send flour up into the air as he kneaded the bread, he had to live in the real world. In the real world, Eijeh was broken, Akos spoke Shotet, and his fate was still his fate.

“Suffer the fate,” he said. “For all else is delusion.”

Cisi sighed. “Thought you might say that. Sometimes delusion’s nice, though.”

“Stay safe, okay?” he said, taking her hand. “I hope you know I don’t want to leave you again. It’s pretty much the last thing I want.”

“I know.” She squeezed his thumb. “I still have faith, you know. That one day you’ll come home, and Eijeh will be better, and Mom will stop with the oracle bullshit, and we can cobble together something again.”

“Yeah.” He tried to smile for her. He might have halfway accomplished it.

She helped him get Isae settled in the escape pod, and Teka told her how to send out a distress signal so the pod would be picked up by Assembly “goons,” as Teka called them. Then Cisi kissed their mom good-bye, and wrapped her arms tight around Akos’s middle until her warmth was pushed all the way through him.

“You’re so damn tall,” she said, softly, as she pulled away. “Who told you that you could be so much taller than me?”

“I did it just to spite you,” he replied with a grin.

Then she got in the pod, and closed the doors. And he didn’t know when he would ever see her again.

Teka tripped up to the captain’s chair on the nav deck and pried the cover of the control panel off with a wedge tool she kept on her belt. She did it while whistling.

“What are you doing?” Cyra asked. “Now’s not really the time to take apart our ship.”

“First, this is my ship, not ‘ours,’” Teka said with a roll of her blue eye. “I designed most of the features that have kept us alive so far. Second, do you really still want to go to Assembly Headquarters?”

“No.” Cyra sat in the first officer’s chair, to Teka’s right. “The last time I went there, I overheard the representative from Trella call my mother a piece of filth. She didn’t think I could understand her, even though she was speaking Othyrian.”

“Figures.” Teka made a scoffing sound in the back of her throat as she pulled out a handful of wires from the control panel, then ran her fingers down them like she was petting an animal. She reached under the wires, to a part of the control panel Akos couldn’t see, so far her entire arm disappeared. A projection of coordinates flashed up ahead, glowing right across the currentstream in their sights. The ship’s nose—Akos was sure there was a technical name for it, but he didn’t know it, so he called it a “nose”—drifted so they were moving toward the currentstream instead of away.

“You going to tell us where we’re headed?” Akos said, stepping up to the nav deck. The control panel was lit up in all different colors, with levers and buttons and switches everywhere. If Teka had spread her arms wide, she still wouldn’t have been able to reach all of them from where she sat.

“I guess I can, since we’re all stuck in this together now,” Teka said. She gathered her bright hair on top of her head, and tied it with a thick band she wore around her wrist. Swimming in a technician’s coveralls, with her legs folded up beneath her on the captain’s chair, she looked like a kid playing pretend. “We’re going to the exile colony. Which is on Ogra.”

Ogra. The “shadow planet,” people called it. It was rare to meet an Ogran, let alone fly a ship in sight of Ogra. It was as far from Thuvhe as any planet could be without leaving the safe band of currentstream that encircled the solar system. No amount of surveillance could poke through its dense, dark atmosphere, and it was a wonder they could get any signal from the news feed. They never fed any stories into it, either, so almost no one had ever seen the planet’s surface, even in images.

Cyra’s eyes, of course, lit up at the information. “Ogra? But how do you communicate with them?”

“The easiest way to transmit messages without the government listening in is through people,” Teka said. “That’s why my mom was on board the sojourn ship—to represent the exiles’ interests among the renegades. We were trying to work together. Anyway, the exile colony is a good place for us to regroup, figure out what’s going on back in Voa.”

“I have a guess,” Akos said, crossing his arms. “Chaos.”

“And then more chaos,” Teka said with a sage nod. “With a short break in between. For chaos, of course.”

He couldn’t imagine what Voa looked like now that—the Shotet believed—Ryzek Noavek had been assassinated by his younger sister right in front of them. That was how it had looked, anyway, when Cyra appeared to cut her brother in the arena, waiting for the sleeping elixir she had arranged for him to drink that morning to kick in and knock him flat. The standing army might have taken over, under the leadership of Vakrez Noavek, Ryzek’s older cousin, or those who lived on the outer edges of the city might have taken to the streets to fill the power vacuum. Either way, Akos imagined streets full of broken glass and blood spatter and ripped paper floating in the wind.