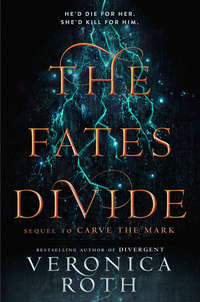

The Fates Divide

But he didn’t say anything, just typed her name into his device and waved her past. She kept her hand in Akos’s, her arm stretched out behind her until he, too, was waved along.

Teka tripped over to them, her eyes wide and shining.

“Amazing, right?” she said, smiling. “I always wanted to see it.”

“You’ve never come before?” Cyra said. “Not even to see your mother?”

“No, I was never allowed to visit her.” There was an edge to her voice. “It wasn’t safe. The exile colony has been here for over two generations, though, ever since the Noaveks came into power.”

“And the Ograns just … let you stay here?” Akos said. “They say anyone who can survive this planet has a right to be here,” Teka said.

“It doesn’t look as dangerous as I was expecting,” Cyra said. “Everyone always talks about how hard it is to survive here, but it seems peaceful enough.”

“Don’t let it fool you,” Teka said. “Everything here is ready to attack or defend—the plants, the animals, even the planet itself. They can’t eat sun, so they eat each other instead—or you.”

“The plants are carnivorous?” Akos said.

“From what I know.” She shrugged. “Or they eat the current. Which probably explains why they’ve been able to survive here—if there’s anything Ogra has a lot of, it’s the current.” She smiled, with some mischief. “And as if the constant threat of being devoured wasn’t enough … well, let’s just say he’s not talking about a little Awakening shower when he says ‘storms.’”

“Cryptic, aren’t you?” Cyra said, frowning.

“Yes!” She grinned. “It’s nice to have the upper hand for once. Come on.”

Teka led them to one of the canals. They had to go down some steps to get to the water’s edge. They were cracked from the tree roots, and uneven. Akos reached down to run his hand over the persistent roots, which were covered in a fine, dark fuzz.

There were plants here. He hadn’t thought about foreign plant species on Pitha, mostly because there were no plants to be found on Pitha, at least not where he could reach them. But Ogra was thick with trees. He wondered, with a thrill of excitement, what you could make with the plants here.

A boat waited at the edge of the canal, long and narrow, with room for only four people across each row of benches. Akos guessed by its glint that it was made of metal. It was dark except for the glow of the water beneath it, a streak of rosy pink.

“What’s that light?” he asked Teka.

But Teka wasn’t the one who answered, it was the woman stationed at the front of the boat, her dark eyes lined with white paint. At first he thought maybe there was a practical reason for the paint, but the longer he looked at her, the more it seemed just decorative, like the black lines people smudged near their eyelashes at home. Here, white just showed up better.

“There are many strains of bacteria that live in Ogra’s waters,” she said. “They light up in different colors. Let them remind you that only our darkest water is safe to drink.”

Even the water could defend itself on Ogra.

Akos followed Teka down the unsteady plank that connected shore to boat, and stepped on one bench to get to another. Cyra settled herself next to him, and he put his hand on her wrist, where the armor ended. He squeezed, and leaned over the edge of the boat to look at the water. The streaks of pink were moving, lazy, with the current of the water.

He tried not to think about Sifa and Eijeh settling in behind them, Sifa’s eyes watchful so his own didn’t have to be. But the boat dipped with their weight, and his stomach sank, too. He couldn’t avoid Eijeh on Ogra like he had on the ship. They were going to be stuck together, the Thuvhesits among Shotet among Ograns.

The woman at the front sat, taking into her hands huge oars that dangled on either side of the vessel. With a sharp yank she drove them forward, her face showing no effort. She was strong.

“A useful currentgift,” Cyra commented.

“It comes in handy every now and then. Most of the time I am called upon to open stubborn jars,” the woman said, as she found a rhythm in her rowing. The ship cut through the water like a hot knife through butter. “Don’t put your hands in the water, by the way.”

“Why not?” Cyra said.

She just laughed.

Akos kept looking over the side, at the changing colors beneath the water’s surface. The pink glow clung to the shallows, near the edge of the canal. Where it was deeper, there were specks of blue, wisps of purple, and wells of deep red.

“There,” the Ogran woman said, and he followed the tilt of her head to a massive shape in the canal. At first he thought it was just more of the bacteria, finding the current. But as they slid past it, he saw it was a creature, twice as wide as their narrow boat and twice again as long. It had a bulbous head—or he assumed it was a head—and at least a dozen tentacles that tapered to feathery ends. He was able to see it only because of how the bacteria clung to it, like paint streaking its smooth sides.

It turned, tentacles twisting together like rope, and on its flank he saw a mouth as big as his own torso, framed all around by sharp, narrow teeth. He stiffened.

“The undersides of these boats are made of a current-shielding material we call ‘soju,’” the Ogran woman said. “The animal—a galansk—is drawn to the current, to devour it. If you put your hand in the water, it would be drawn to you. But it can’t sense us in this boat.”

And true to her word, with the next pull of her oars, the galansk turned again, and dove deep, becoming just a faint glow under the surface of the water. A moment later it was gone.

“You mine this metal here?” Teka asked the woman.

“No, no. There is nothing on this planet that is not current-rich,” the woman said. “We import soju from Essander.”

“Why do you live on a planet so determined to kill you?” he said.

The Ogran woman smiled at him. “I could ask the Shotet the same question.”

“I’m not Shotet,” he said.

“Are you not?” she said with a shrug, and continued to row.

His back ached by the time they got to their destination, from the stress of the landing followed by sitting on the uncomfortable bench in the boat. The Ogran woman steered them toward the edge of the canal, where there were stone steps overrun with the same velvet-soft wood he had touched earlier. Next to the steps was the yawn of a tunnel.

“We must go underground to avoid the storms,” she said. “You can explore the Shotet sector another time.”

The storms. She said it reverently, but not fondly—it was something she feared, this woman with the strength of half a dozen people, and that made Akos fear it, too.

He climbed out of the boat on unsteady legs, relieved to find solid ground. He reached back to help Cyra, his mouth drawn into a thin line.

“I thought the Shotet were fierce,” he said. “But the people here must be downright lethal.”

“A different kind of ferocity, perhaps,” she said. “They don’t hesitate, but they fight without finesse. It’s a kind of … clumsy courage. And a kind of madness, too, to live in a place like this.”

Akos knew, listening to her, that she had spent more time observing the Ograns than she would ever admit to—that she didn’t even realize there was anything to admit to, because she assumed all other people were as inquisitive as she was. She had likely watched every piece of footage of Ogran combat she could get her hands on, and half a dozen other subjects, besides. All those files were stored in her quarters on the sojourn ship, her little den of knowledge.

They walked into the tunnel, led at first by the Ogran woman’s whistling alone. But ten paces in, Akos saw light. Some of the stones in the walls of the tunnel were glowing. They were small, smaller than his fist, and set at random into the walls and ceiling.

The woman whistled louder, and the stones grew brighter. Akos pursed his lips, hiding his face as he tried a whistle of his own. The light in the stones near him went white, with the warmth of sunlight. Was this as close to sunlight as Ogra ever got?

He glanced at Cyra. She winced, the currentshadows lively across the back of her neck, but she was smiling at him.

“What?” he said.

“You’re excited,” she said. “This planet is probably going to kill us, and you love it.”

“Well,” he said, feeling defensive, “it’s fascinating, that’s all.”

“I know,” she said. “It’s just, I don’t expect other people to love the odd and dangerous things I love.”

She draped her arm around his waist, her touch light, so he didn’t feel her weight. He leaned into her, slinging his own arm over her shoulders. Her skin went blank again at his touch.

Then he heard it—the low rumble, like the planet itself was growling, and at this point, he wouldn’t have been surprised to hear that it was.

“Come along, ice-dwellers,” the Ogran woman sang, her voice ringing.

She reached down and stuck her pinkie through something—a metal loop in the dark floor. With a flick of her wrist, a trapdoor pulled up from the ground, scattering dust. Akos spotted narrow stairs that disappeared into nothingness.

Well, he thought, time to summon some Shotet mettle.

THE LAST TIME I had walked into a crowd, it was to pretend to kill my own brother, and they had thirsted for my blood.

And before that, he had carved my skin from my head to the tune of hundreds of cheers. I reached up to touch the silverskin that covered me from throat to jaw to skull.

No, I did not have pleasant memories of crowds, and I was not likely to form them here, with only Ograns and Shotet exiles waiting for me.

We had walked down the dark stairs, feeling our way with the soles of our shoes and the brushes of our fingers, and turned a sharp corner, and here we were: in a dim waiting space with creaky wood floors, and the glow of Ogran clothing, most of which adorned Shotet bodies, though I only knew because of the language they spoke.

Ogran clothing—which even the Shotet wore, here—had no real distinct style, some of it tight and some flowing, some ornate and some simple, but the embrace of that ever-present glow was there, in bracelets and anklets and necklaces, shoelaces and belts and buttons. One man I passed even had stripes of red light—faint, but still, light—stitched into the back of his jacket. It gave everyone an eerie look, lit from beneath by their garments, their faces difficult to see. Those with fair skin, like Akos’s, almost gave off their own light—not an advantage on a planet as hostile as this.

There were benches for sitting, and high tables for standing around. Some held glasses with a clear substance that scattered light inside them. I watched a bottle passed through a group of people, bobbing along like their hands were waves. Children sat in a circle near my feet, playing a game with quick hand motions passed in a round. Two boys, a few seasons younger than me, play-fought near one of the massive room’s wooden pillars. This was a space for gathering and, I sensed, not much else; this was not where the Shotet lived, or worked, or ate, but just a space to wait out the storms. The Ogran woman had remained vague about what “the storms” actually were. Not surprising. Ograns seemed to trade in vague language and weighty looks.

Teka melded into the crowd right away, throwing her arms around the nearest exile she recognized. That was when people began to take notice of us—Teka, with her pale skin and even paler hair, required no introduction. Akos was a head taller than most people in the room, and drew eyes naturally.

And then there was me. Glinting silverskin and currentshadows crawling all over my body.

I tried not to tense as some people went quiet at the sight of me, and others muttered, or pointed—who had taught them manners?

I was used to this sort of reaction, I reminded myself. I was Cyra Noavek. Guards at the manor backed away from me instinctively, women held their children near at the sight of me. I drew myself up straighter, taller, and shook my head when Akos reached for me, to help me with my pain. No, better to let them see me as I was. Better to get this over with.

I pretended I was not breathing harder.

“Hey.” Teka pinched the elbow of my oddly sized mechanic’s jumpsuit and tugged. “Come on, we should introduce ourselves to the leadership.”

“You don’t know them already?” I said, as Akos searched behind him—for his mother and brother, I assumed, though he had been avoiding them since we landed.

I tried to imagine how I would have acted if my mother had returned to my life after I had accepted that I would never see her again. In my mind, it was a happy reunion, and we fell into our old rhythms of care and understanding. It certainly wasn’t that simple for Akos, with the history of betrayal and subterfuge that existed between him and Sifa, but even without that, perhaps it was never simple. Perhaps I would have avoided Ylira just as he avoided his mother.

Or maybe it was just that she spoke in riddles, and it was exhausting.

Once Akos had rounded up his family, we all followed Teka deeper into the room. I tried to keep myself from marching, though that was my instinct—scare them on purpose, so I didn’t have to watch them grow frightened by accident.

“So we’re right near the village of Galo,” Teka said. “It’s mostly full of Shotet exiles now, but there are still some Ograns who live here. Merchants, mostly. My mother said we’d integrated pretty well—oh!”

Teka threw her arms around a pale-haired man with a mug in hand, then shook hands with a woman with a shaved head, who tapped Teka’s eye patch in gentle mocking.

“I’m saving my fancy one for a special occasion,” Teka replied. “Do you know where Ettrek is? I have to introduce him to—ah.”

A man had stepped forward, tall, though not as tall as Akos, with long dark hair drawn up into a knot. I couldn’t decide, in this light, if he was my age or ten seasons older. The rumble in his voice didn’t do much to help.

“Ah, here she is,” the man said. “Ryzek’s Scourge turned Ryzek’s Executioner.”

He put an arm around me, turning as if to draw me into a group of people all holding glasses of whatever-it-was. I pulled away from him so quickly he might not have had the chance to feel my currentgift.

Pain darted across my cheek, and followed my next swallow down my throat. “Call me that again and I will—”

“What? Hurt me?” The man smirked. “It would be interesting to see you try. Then we would see if you are as good at fighting as they say.”

“Regardless of whether I am a good fighter or not,” I snapped, “I am not Ryzek’s ‘Executioner.’”

“So humble!” an older woman across from me said, tipping some of her drink into her mouth. “We all saw what you did on the news feed, Miss Noavek. There’s no need to be shy about it.”

“I am neither shy nor humble,” I said, feeling my mouth twist into my sourest smile. My head was pounding. “I just don’t believe everything I see. You should have learned that lesson well enough, exile.”

I almost laughed, seeing all their eyebrows pop up in unison. Akos touched my shoulder, the part covered with fabric, and bent closer to my ear.

“Slow down on making enemies,” he said. “There’s plenty of time for that later.”

I stifled a laugh. He had a point, though.

At first, all I saw next was a broad smile in the dark, and then Jorek collided with Akos. Akos looked too confused to return the embrace—actually, he didn’t seem particularly affectionate, as a rule, I had noticed—but he managed to give Jorek a good-natured slap on the shoulder as he pulled away.

“Took you long enough to get here,” Jorek said. “I was beginning to think you guys got kidnapped by the chancellor.”

“No,” Akos said. “Actually, we abandoned her in an escape pod.”

“Really?” Jorek’s eyebrows popped up. “That’s sort of a shame. I liked her.”

“You liked her?” I said.

“Miss Noavek,” Jorek said, bobbing his head to me. He turned back to Akos. “Yeah, she was a little scary, and apparently I gravitate toward that quality in friends.”

My cheeks warmed as he looked from Akos to me and back again, pointedly. Jorek thought of me as a friend?

“How’s your mom?” Akos said to him. “Is she here?”

Jorek had stayed behind after our little mission to ensure that his mother made it through the chaos of Voa.

“Safe and sound, but no, she’s not here,” Jorek said. “She said if she ever manages to land on Ogra, she’s never going to try to take off again. No, she’s keeping an eye on things for us in Voa. Moved in with her brother and his children.”

“Good,” Akos said. He scratched the back of his neck, and his fingertips scraped along the thin chain he wore, the one with the ring Ara Kuzar had given him hanging from the end of it. He didn’t wear it out of affection, as Ara and Jorek had undoubtedly hoped he would, but as a burden. A reminder.

Teka had disappeared for a moment, but she returned now with a sturdy woman at her side. She was not tall or short, really, and her hair was pulled back into a tight braid. The smile she gave me was warm enough, though like the others, she didn’t even glance in Akos’s direction. Her attention was solely mine.

“Miss Noavek,” the woman said, offering your hand. “I am Aza. I sit on our council here.”

I glanced at Akos, asking a silent question. He rested his hand on the bare skin where my neck met my shoulder, extinguishing my currentshadows. I knew without trying that I was not capable of controlling my gift right now, as I had learned to in the renegade hideout in Voa. Not in Ogra’s currentgift-enhancing atmosphere, with days of limited sleep behind me. It was taking all the energy I had just to keep it contained, so it wouldn’t explode out of me as it had when we first landed.

I took the woman’s hand, and shook it. Akos may not have commanded her attention before, but his ability to extinguish my gift certainly did. In fact, everyone around us looked at him—specifically, at the hand he kept on my skin.

“Call me Cyra, please,” I said to Aza.

Aza’s gaze was curious, and sharp. When I dropped her hand, Akos dropped his, and my currentshadows returned. His cheeks were bright with color, and it was spreading to his neck.

“And you are?” Aza asked him.

“Akos Kereseth,” he said, a little too quietly. I wasn’t used to the meek side of him, but now that we weren’t constantly surrounded by the people who had kidnapped him or killed his father or otherwise tormented him—well. Perhaps this was what he was like, under somewhat more normal circumstances.

“Kereseth,” Aza repeated. “It’s funny—for the duration of this exile colony’s existence, we have never had a fated person pass through our doors. And now we have two.”

“Four, actually,” I said. “Akos’s older brother Eijeh is … somewhere. And his mother, Sifa. They’re both oracles.”

I cast a glance around for both of them. Sifa emerged from the shadows behind me, almost as if summoned by her name alone. Eijeh was a few paces behind her.

“Oracles. Two oracles,” Aza said. She was finally startled, it seemed.

“Aza,” Sifa said, nodding. She wore a smile intended, I was sure, to be inscrutable. I almost rolled my eyes.

“Thank you for sheltering us,” Sifa said. “All of you. We have walked a hard road to get here.”

“Of course,” Aza said stiffly. “The storms will be over soon, and we will be able to find a place for you to rest.” Aza stepped closer. “But I must ask, Oracle … should we be concerned?”

Sifa smiled. “Why do you ask?”

“Hosting two oracles at once seems like …” Aza frowned. “Not a good sign for the future.”

“The answer to your question is yes. Now is indeed the time for concern,” Sifa said softly. “But that would be the case whether I was here or not.”

She tilted her head, and another Ogran woman—this one fair-skinned, dotted with freckles, and wearing bracelets that lit up a gentle white—stepped forward. The bracelets helped me to see her face when she gestured to me, whispering in Ettrek’s ear.

“Miss Noavek,” the Ogran woman said then, when her whispering was finished. Her eyes—as dark as my own—followed the currentshadows that now cradled my throat like a choking hand, and felt much the same. “My name is Yssa, and I have just heard from someone in our communications tower. We have received a call for you, from Assembly Headquarters.”

“For me?” I raised my eyebrows. “Surely you’re mistaken.”

“The recording was broadcast on the Assembly-wide news feed a few hours ago. That is as quickly as we can receive them on Ogra. Unfortunately, this one has a time limit,” she said. “The message is from Isae Benesit. If you wish to respond, you must be prepared to act immediately.”

“What?” I demanded. I felt a buzzing in my chest, like the hum of the current but stronger, more visceral. “I have to respond immediately?”

“Yes,” Yssa said. “Or you will not get back to her in time. Our communications delay is regrettable, but there is no way to bypass it. We can record you from here and send the footage up to the next satellite, which departs our atmosphere in just minutes. Otherwise we must wait another hour. Come with me, please.”

I reached for Akos’s hand. He gave it, and held on tight, and we followed Yssa through the crowd.

Yssa had the message cued to a screen on the far wall. It was as large as I was with my arms outstretched. She had me stand on a mark on the floor, shooed away everyone who was standing around me—including Akos—and turned on a light that cast my face in yellow. This was for the camera that would record my message, I assumed.

I had been instructed in matters of diplomacy by my mother, but only as a child. After her death, neither my father nor my brother had bothered to continue that part of my education. They had assumed—reasonably—that I would never need to know those things, weaponized girl that I was. I tried to remember what she had told me. Stand up straight. Speak clearly. Don’t be afraid to think about your answer—the pause feels longer to you than it does to them. That was all I could remember. It would have to be enough.

Isae Benesit appeared on the screen before me, larger now than she had ever been in life. Her face was uncovered—the disguise was unnecessary now that her sister had been killed, I assumed, and the two could no longer be confused for each other. The scars stood out from her skin, prominent but not garish. Though the rest of her face was painted with makeup, the scars had been left alone. At her insistence, I assumed.

Her black hair shone, pulled back from her face, and she wore a high-collared dress—I assumed, I could only see to her waist—made of a thick, black material that looked almost liquid. An off-center button shone gold against her throat. And there was a gold band around her forehead. A crown, of sorts, though the least ornamental one I had ever seen. This was not a chancellor who wanted to be associated with the abundance and wealth of Othyr. This chancellor led Osoc, Shissa, and most important, Hessa. The very heart of Thuvhe.

She appeared to have taken great pains not to appear pretty or delicate. She was striking, eyes lined in careful black, skin left to its usual olive tone without embellishment other than powder to limit its shine.

I, meanwhile, hadn’t had a proper bath in over a week, and I was wearing an ill-fitting jumpsuit.

Wonderful.

“This is Isae Benesit, Fated Chancellor of Thuvhe, speaking on behalf of the nation-planet of Thuvhe,” she began. The room went quiet around me. I squeezed my hands into fists at my sides. Pain raced through my body, sparking in my feet and spreading through my legs and around my abdomen.