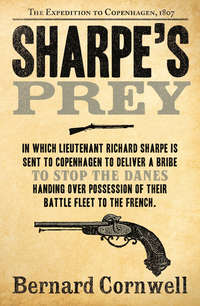

Sharpe’s Prey: The Expedition to Copenhagen, 1807

‘I will, sir.’

The two officers did not speak as they were rowed out to the Cleopatra which, in her haste to use a favourable wind and tide, was already hauling her anchor. Sharpe could hear the chant of the seamen as they tramped round the capstan and see the quivering cable shedding drops of water and lumps of mud as it came from the grey river. The topmen were aloft, ready to drop the high sails. Sharpe and Lavisser scrambled up the ship’s side to be met by the dutiful squeal of bosuns’ whistles and by a harassed lieutenant who hurried them aft to the quarterdeck while the hulking Barker carried the baggage down below and a dozen seamen hauled a line to bring the gold on deck. ‘Captain Samuels begs to be excused while we get under way,’ the Lieutenant said, ‘and requests that you keep to the stern rail, gentlemen, until the sails are set.’

Lavisser grinned as the Lieutenant hurried away. ‘Meaning that Captain Samuels don’t want us in the way while he makes a muck of getting under sail. And he’s under the eye of the Admiral, no less! Rather like setting the guard at Windsor Castle. I don’t suppose you’ve ever done that, Sharpe? Placed a guard at Windsor?’

‘I haven’t, sir,’ Sharpe said.

‘You do it perfectly, then some decrepit old fool who last saw action fighting against William the Conqueror informs you that Guardsman Bloggs has an ill-set flint in his musket. And for God’s sake stop calling me “sir”,’ Lavisser said with a smile. ‘You make me feel old, and that’s dreadful unkind of you. So what was on that piece of paper little William gave to you?’

‘Little William?’

‘Lord Pumps. He was a pallid little worm at Eton and he’s no better now.’

‘It’s just his address,’ Sharpe said. ‘He says I should report to him when I get back.’

‘Nonsense,’ Lavisser said, though he did not appear offended that Sharpe had lied to him. ‘If my guess is any good then it’s the name of a man in Copenhagen who might help us, a name, I might add, that the suspicious bastards at the Foreign Office refused to give me. Divide and rule, that’s the Foreign Office way. Aren’t you going to tell me the name?’

‘If I remember it,’ Sharpe said. ‘I threw the paper overboard.’

Lavisser laughed at that untruth. ‘Don’t tell me little Pumps told you to keep it secret! He did? Poor little Pumps, he sees conspiracy everywhere. Well, so long as one of us has the name I suppose it don’t matter.’ He looked upwards as the topsails were released. The canvas shook loudly until the seamen sheeted the sails home. Men slid down shrouds and scrambled along spars to loose the mainsails. It was all so very familiar to Sharpe after his long voyage home from India. Captain Samuels, heavy and tall, stood at the white line which marked off the quarterdeck from the rest of the flush-decked frigate. He said nothing, just watched his men.

‘How long a voyage is it?’ Sharpe asked Lavisser.

‘A week? Ten days? Sometimes much longer. It all depends on Aeolus, our god of the winds. May he blow us swiftly and safely.’

Sharpe grunted an acknowledgement, then just stared ashore where the herring smokers made a haze over the land. He leaned on the stern rail, suddenly wishing he was anywhere but at sea.

Lavisser leaned on the rail beside him. ‘You ain’t happy, Sharpe,’ the guardsman said. Sharpe frowned at the words, which struck him as intrusive. He said nothing, but was acutely aware of Lavisser so close beside him. ‘Let me guess.’ The Guards Captain raised his eyes to the wheeling gulls and pretended to think for a while, then looked at Sharpe again. ‘My guess, Sharpe, is that you met Lady Grace Hale on shipboard and that you’ve not been afloat since.’ He held up a cautionary hand when he saw the anger in Sharpe’s eyes. ‘My dear Sharpe, please don’t mistake me. I feel for you, indeed I do. I met the Lady Grace once. Let me see? It must be a dozen years or more ago and I was only a sprat of fifteen, but I could spot a beauty even then. She was lovely.’

Sharpe said nothing, just watched Lavisser.

‘She was lovely and she was clever,’ the Guards Captain went on softly, ‘and then she was married off to a tedious old bore. And you, Sharpe, forgive my being forward, gave her a time of happiness. Isn’t that something to remember with satisfaction?’ Lavisser waited for Sharpe to respond, but the rifleman said nothing. ‘Am I right?’ Lavisser asked gently.

‘She left me in bloody misery,’ Sharpe admitted. ‘I can’t seem to shake it. And, yes, being on a ship brings it back.’

‘Why should you shake it?’ Lavisser asked. ‘My dear Sharpe, may I call you Richard? That’s kind of you. My dear Richard, you should be in mourning. She deserves it. The greater the affection, the greater the mourning. And it’s been cruel for you. All the gossip! It’s no one’s business what you and Lady Grace did.’

‘It was everyone’s business,’ Sharpe said bitterly.

‘And it will pass,’ Lavisser said gently. ‘Gossip is ephemeral, Richard, it vanishes like dew or smoke. Your grief remains, the rest of the world will forget. They’ve mostly forgotten already.’

‘You haven’t.’

Lavisser smiled. ‘I’ve been racking my brains all day trying to place you. It only came to me as we climbed aboard.’ A rush of feet interrupted them as seamen came aft to secure the mizzen sheets. The great sail banged above their heads, then was brought under control and the frigate picked up speed. Her ensign, blue because the fleet’s commander was an Admiral of the Blue, flapped crisply in the evening wind. ‘The grief will pass, Richard,’ Lavisser went on in a low voice, ‘it will pass. I had a sister who died, a dear thing, and I grieved for her. It’s not the same, I know, but we should not be ashamed of demonstrating our feelings. Not when it is grief for a lovely woman.’

‘It won’t stop me doing my job,’ Sharpe said stoically, fighting off the tears that threatened.

‘Of course it won’t,’ Lavisser said fervently, ‘nor, I trust, will it stop you from enjoying the fleshpots of Copenhagen. They are meagre and few, I can assure you, but such as they are we shall enjoy.’

‘I can’t afford fleshpots,’ Sharpe said.

‘Don’t be so dull, Richard! We’re sailing with forty-three thousand of the government’s guineas and I intend to steal as many of them as I decently can without getting caught.’ He smiled so broadly and with such infectious enjoyment that Sharpe had to laugh. ‘There!’ Lavisser said. ‘You see I shall be good for you!’

‘I hope so,’ Sharpe replied. He was watching the Cleopatra’s rippling wake. The tide was ebbing and the wind was out of the west so that the anchored ships presented their sterns to the frigate’s quarterdeck. The ugly bomb ships sat low in the water. One was called Thunder, another Vesuvius, then there was Aetna with Zebra close by. The frigate sailed so close to Zebra that Sharpe could look down into her welldeck which was stuffed with what looked like coils of rope, put there to cushion the shock of the two great mortars that squatted in the ship’s belly. The mortars were capped with tompions, but Sharpe guessed they threw a shell about a foot across and, because the flash of their firing would blast up into the air to lob the bombs in a high arc, the forward stays of the Zebra were not made of hemp, but of thick chain. Another eight guns, carronades by the look of them, were mounted aft of the mainmast. An ugly vessel, Sharpe thought, but a brute with massive teeth, and there were sixteen of the bomb ships moored or anchored in the river, along with a host of gun brigs that were shallow-draught vessels armed with heavy cannon. These were not ships designed to fight other ships, but to hammer targets ashore.

The Cleopatra was picking up speed now as the crew trimmed the big sails. She leaned to larboard and the water began to gurgle and seethe at her stern. The dusk was drawing in, shadowing the big seventy-fours that were the workhorses of the British fleet. Sharpe recognized some of the ships’ names from Trafalgar: the Mars, the Minotaur, the Orion and the Agamemnon, but most he had never seen before. The Goliath, belying her name, was dwarfed by the Prince of Wales, a 98-gun monster which flew the Admiral’s pennant. A gunport opened at the Prince of Wales’s bow to return the salute that the Cleopatra was firing as she passed. The sound of the guns was huge, the smoke thick and the tremor of the cannon, even though they were unshotted, shook the deck beneath Sharpe’s feet.

Only one ship, another seventy-four, lay beyond the Prince of Wales. She was a good-looking ship and Sharpe had learned enough in his voyage home from India to recognize that she was French-built, one of the many ships that had been captured from the enemy. Water gushed from her pumps as the Cleopatra sailed by and Sharpe looked up to see men pausing in their work to watch the sleek frigate pass. Then the Cleopatra left the seventy-four behind and Sharpe could read the gold-painted name scrolled across her stern. Pucelle. His heart leaped. The Pucelle! His own ship, the ship he had been aboard at Trafalgar and which was captained by his friend, Joel Chase, though whether Chase was still a captain, or aboard the Pucelle or even alive, Sharpe did not know. He just knew that he and Grace had known happiness on board the ship that had been named by her French builders for Joan of Arc, la pucelle or the virgin. He wanted to wave at the ship, but it was too far for him to recognize anyone aboard.

‘You’re welcome, gentlemen.’ Captain Samuels, dark-faced, grey-haired and scowling, had come to greet his guests. ‘Lieutenant Dunbar will show you your quarters.’ He frowned at Sharpe, who had turned to stare at the Pucelle again. ‘You find my remarks tedious, Lieutenant?’

‘I’m sorry, sir. I was aboard that ship once.’

‘The Pucelle?’

‘Didn’t she take the Revenant at Trafalgar, sir?’

‘What if she did? There were easy pickings at that battle, Lieutenant.’ The envy of a man who had not sailed with Nelson was naked in Samuels’s voice.

‘You were there, sir?’ Sharpe asked, knowing it would needle the Captain.

‘I was not, but nor were you, Lieutenant, and now you will show me the courtesy of remarking my words.’ He went on to tell them the rules of the ship, that they were not to smoke aboard, not to climb the rigging and that they must salute the quarterdeck. ‘You will take your meals in the officers’ mess and I’ll thank you not to get in the crew’s way. I’ll do my duty, God knows, but that doesn’t mean I must like it. I’m to put you and your damned cargo ashore by stealth and that I’ll do, but I’ll be glad to see the back of you both and get back to some proper sailoring.’ He left them as abruptly as he had come.

‘I do love feeling welcome,’ Lavisser murmured.

Sharpe stared aft again, but the Pucelle was lost in the dark loom of the land. She was gone and he was sailing away again. Sailing to a war, or to stop a war, or to be tangled in treachery, but whatever it was, he was still a soldier.

Sharpe was a soldier without weapons. He had come aboard the Cleopatra with his official-issue sabre, but nothing else. Nothing useful. He complained of it to Lavisser who said Sharpe could be amply supplied in Vygârd. ‘It’s the house where my mother grew up and it’s rather beautiful.’ He sounded wistful. ‘My grandfather has anything you might need; pistols, swords, everything, though I truly doubt we’ll encounter trouble. I’m sure the French do have agents in Copenhagen, but they’re hardly likely to try murder.’

‘Where’s Vygârd?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Near Køge where our hospitable Captain is supposed to put us ashore.’ They were eleven days out of Harwich, sailing a sunlit sea. Lavisser was leaning on the stern rail where he looked as though he did not have a care in the world. He wore no hat and his golden hair lifted in the wind. He had blue eyes and a sharp-cut face, so that he looked like one of his Viking ancestors who had sailed this same cold sea. ‘You really won’t need weapons, Richard,’ Lavisser went on. ‘We’ll simply borrow a carriage from Vygârd to carry the gold to Copenhagen, conclude our business with the Crown Prince and so have the satisfaction of preserving peace.’

Lavisser had spoken confidently, but Sharpe recalled Lord Pumphrey’s doubts that the Danish Crown Prince was a man open to bribery. ‘What if the Crown Prince refuses?’ he asked.

‘He won’t,’ Lavisser said. ‘My grandfather is his chamberlain and he tells me that the bribe is the Prince’s own suggestion.’ He smiled. ‘He needs money, Sharpe, to rebuild the Christiansborg Palace that got burned down a few years back. It will all be very easy and we shall go home as heroes. Where’s the danger? There are no Frogs in Vygârd, none in my grandfather’s town house in Bredgade, and the Prince’s own guards will keep the bastards well out of our way. You really do not need weapons, Richard. Indeed, I don’t wish to offend you, but your own presence, though utterly welcome, is also superfluous.’

‘Things can go wrong,’ Sharpe said stubbornly.

‘How very true. An earthquake could devastate Copenhagen. Maybe there will be a plague of toads. Perhaps the four horsemen of the apocalypse will ravage Denmark. Richard! I’m going home. I’m calling on a prince to whom I am distantly related. Like me, he’s half English. Did you know that? His mother is King George’s sister.’

Lavisser was persuasive, but Sharpe felt naked without proper weapons and other men who were senior to Lavisser had thought it wise to give the guardsman protection and so Sharpe went below to the tiny cabin that he shared with Lavisser and there pulled open his pack. His civilian clothes were inside, the good clothes that Grace had bought for him, along with the telescope that had been a grudging gift from Sir Arthur Wellesley. But at the very bottom of the canvas pack, hidden and half forgotten, was his old picklock. He pulled it out, then unfolded the slightly rusting picks. Grace had discovered it once and wondered what on earth it was. She had laughed in disbelief when he told her. ‘You could be hanged for possessing such a thing!’ she had declared.

‘I keep it for old times’ sake,’ Sharpe had explained lamely.

‘You’ve never used it, surely?’

‘Of course I’ve used it!’

‘Show me! Show me!’

He had shown her how to pick a lock, a thing he had done scores of times in the past. He was out of practice now, but the picks still made brief work of the padlock which secured the great chest in which the government money was stored. There were plenty of weapons on board the Cleopatra, but to get some Sharpe knew he would have to cross some tar-stained hands with gold.

Sharpe had money of his own. He had taken twenty-four pounds, eight shillings and fourpence halfpenny from Jem Hocking and the bulk of that had been in coppers and small silver which Sergeant Matthew Standfast, the new owner of the Frog Prick, had been happy to exchange for gold. ‘At a price, sir,’ Standfast had insisted.

‘A price?’

‘Filthy stuff!’ Standfast had poked the grimy coppers. ‘I’ll have to boil them in vinegar! What have you been doing, Lieutenant? Robbing poor boxes?’ He had exchanged the twenty-four pounds, eight shillings and fourpence halfpenny for twenty-two shining guineas that were now safely wrapped in one of Sharpe’s spare shirts.

He could have used his own money to get weapons, but he did not see why he should. Britain was sending him to Denmark and it was Britain’s enemies who threatened Lavisser, so Britain, Sharpe reckoned, should pay, and that meant taking gold from the big chest that half filled the cabin that Sharpe and Lavisser shared. Sharpe had to edge one of the hanging cot beds aside to open the chest’s lid. Inside were layers of grey canvas bags secured with wire ties that were sealed with crimped lead tags blobbed with red wax. Sharpe lifted three bags from the top layer and selected a lower bag that he slit with his knife.

Guineas. The golden horsemen of Saint George. Sharpe lifted one, looking at the image of the saint lancing the writhing dragon. Rich, thick, gold coins, and the chest had enough to suborn a kingdom, but it could spare a little for Lieutenant Sharpe and so he stole fifteen of the heavy coins that he secreted in his pockets before restoring the bags. He was just putting the last one in place when there was the thud of feet dropping down the companionway ladder immediately outside the cabin. Sharpe closed the chest lid and sat on it to hide the absence of a padlock. The cabin door opened and Barker came in with a bucket. He saw Sharpe and paused.

Sharpe pretended to be pulling on his boots. He looked up at the hulking Barker who had to stoop beneath the beams. ‘So you were a footpad, Barker?’

‘That’s what the Captain told you.’ Barker put the bucket down.

‘Where?’ Sharpe asked.

Barker hesitated, as if suspecting a trap in the question, then shrugged. ‘Bristol.’

‘Don’t know it,’ Sharpe said airily. ‘And now you’re reformed?’

‘Am I?’

‘Are you?’

Barker grimaced. ‘I’m looking for Mister Lavisser’s coat.’

Sharpe could see the padlock in a corner of the cabin and hoped Barker did not notice it. ‘So what will you do if the French interfere with us?’

Barker scowled at Sharpe. It seemed as if he had not understood the question, or else he just hated talking to Sharpe, but then he sneered. ‘How will they even know we’re there? The master speaks Danish and you and I will keep our gobs shut.’ He plucked a coat from a hook on the back of the door and left without another word.

Sharpe waited for his steps to fade, then restored the padlock to the hasp. He did not like Barker and the feeling was evidently mutual. On the face of it the man made a strange servant for Lavisser, yet Sharpe had met plenty of gentlemen who liked to mix with brutes from the gutter. Such men enjoyed listening to the stories and felt flattered by the friendships, and presumably Lavisser shared their taste. Maybe, Sharpe reflected, that explained why Lavisser was being so friendly to himself.

Next day he used two of the guineas to bribe the ship’s Master-at-Arms who made the gold vanish into a pocket with the speed of a conjurer and an hour later brought Sharpe a well-honed cutlass and two heavy sea-service pistols with a bag of cartridges. ‘I’d be obliged, sir, if Captain Samuels didn’t know about this,’ the Master-at-Arms said, ‘on account that he’s a flogger when he’s aggravated. Keep ’em hidden till you’re ashore, sir.’ Sharpe promised he would. There would be no difficulty in keeping the promise during the voyage, but he did not see how he was to carry the weapons off the ship without Captain Samuels seeing them, then thought of the chest. He asked Lavisser to put them with the gold.

Lavisser laughed when he saw the cutlass and heavy-barrelled guns. ‘You couldn’t wait till we reached Vygârd?’

‘I like to know I’m armed,’ Sharpe said.

‘Armed? You’ll look like Bluebeard if you carry that lot! But if it makes you happy, Richard, why not? Your happiness is my prime concern.’ Lavisser took the chest’s key from a waistcoat pocket and raised the lid. ‘A sight to warm your chill heart, eh?’ he said, indicating the dull grey bags. ‘A fortune in every one. I fetched it myself from the Bank of England and, Lord, what a fuss! Little men in pink coats demanding signatures, enough keys to lock up half the world, and deep suspicion. I’m sure they thought I was going to steal the gold. And why not? Why don’t you and I just divide it and retire somewhere gracious? Naples? I’ve always wanted to visit Naples where I’m told the women are heartbreakingly beautiful.’ Lavisser saw Sharpe’s expression and laughed. ‘For a man up from the ranks, Richard, you’re uncommonly easy to shock. But I confess I’m tempted. I suffer the cruel fate of being the younger son. My wretched brother will become earl and inherit the money while I am expected to fend for myself. You find that risible, yes? Where you come from everyone fends for themselves, so I shall do the same.’ He put Sharpe’s new weapons on the grey bags, then closed the chest. ‘The gold will go to Prince Frederick,’ he said, securing the padlock, ‘and there will be peace on earth and goodwill to all mankind.’

Next evening the frigate passed the northernmost tip of Jutland. The low headland was called the Skaw and it showed dull and misty in the grey twilight. A beacon burned at its tip and the light stayed in view as the Cleopatra turned south towards the Kattegat. Captain Samuels was plainly worried about that narrow stretch of water, in one place only three miles wide, which was the entrance to the Baltic and guarded on its Swedish bank by the great cannon of Helsingborg and on the Danish by the batteries of Helsingør’s Kronborg Castle. The frigate had seen few other ships between Harwich and the Skaw, merely a handful of fishing boats and a wallowing Baltic trader with her main deck heavily laden with timber, but now, sailing into the narrowing gut between Denmark and Sweden, the traffic was heavier. ‘What we don’t know’ – Captain Samuels deigned to speak to Sharpe and Lavisser on the morning after they had passed the Skaw – ‘is whether Denmark is still neutral. We can pass Helsingør by staying close to the Swedish shore, but the Danes will still see us pass and know we’re up to no good.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов