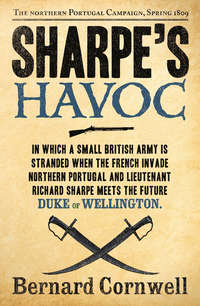

Sharpe’s Havoc: The Northern Portugal Campaign, Spring 1809

‘Whitehall? The Horse Guards?’

‘Dear me, no,’ Hogan had said. The Horse Guards were the headquarters of the army and it was plain Hogan believed Christopher came from somewhere altogether more sinister. ‘The world is a convoluted place, Richard,’ he had explained, ‘and the Foreign Office believes that we soldiers are clumsy fellows, so they like to have their own people on the ground to patch up our mistakes. And, of course, to find things out.’ Which was what Lieutenant Colonel Christopher appeared to be doing: finding things out. ‘He says he’s mapping their minds,’ Hogan had mused, ‘and what I think he means by that is discovering whether Portugal is worth defending. Whether they’ll fight. And when he knows, he’ll tell the Foreign Office before he tells General Cradock.’

‘Of course it’s worth defending,’ Sharpe had protested.

‘Is it? If you look carefully, Richard, you might notice that Portugal is in a state of collapse.’ There was a lamentable truth in Hogan’s grim words. The Portuguese royal family had fled to Brazil, leaving the country leaderless, and after their departure there had been riots in Lisbon, and many of Portugal’s aristocrats were now more concerned with protecting themselves from the mob than defending their country against the French. Scores of the army’s officers had already defected, joining the Portuguese Legion that fought for the enemy, and what officers remained were largely untrained, their men were a rabble and armed with ancient weapons if they possessed weapons at all. In some places, like Oporto itself, all civil rule had collapsed and the streets were governed by the whims of the ordenança who, lacking proper weapons, patrolled the streets with pikes, spears, axes and mattocks. Before the French had come the ordenança had massacred half Oporto’s gentry and forced the other half to flee or barricade their houses though they had left the English residents alone.

So Portugal was in a state of collapse, but Sharpe had also seen how the common people hated the French, and how the soldiers had slowed as they passed the gate of the House Beautiful. Oporto might be falling to the enemy, but there was plenty of fight left in Portugal, though it was hard to believe that as yet more soldiers followed the retreating six-pounder gun down to the river. Lieutenant Colonel Christopher glanced at the fugitives, then looked back at Sharpe. ‘What on earth was Captain Hogan thinking of?’ he asked, evidently expecting no answer. ‘What possible use could you be to me? Your presence can only slow me down. I suppose Hogan was being chivalrous,’ Christopher went on, ‘but the man plainly has no more common sense than a pickled onion. You can go back to him, Sharpe, and tell him that I don’t need assistance in rescuing one damned silly little girl.’ The Colonel had to raise his voice because the sound of cannons and musketry was suddenly loud.

‘He gave me an order, sir,’ Sharpe said stubbornly.

‘And I’m giving you another,’ Christopher said in the indulgent tone he might have used to address a very small child. The pommel of his saddle was broad and flat to make a small writing surface and now he laid a notebook on that makeshift desk and took out a pencil, and just then another of the red-blossomed trees on the crest was struck by a cannonball so that the air was filled with drifting petals. ‘The French are at war with the cherries,’ Christopher said lightly.

‘With Judas,’ Sharpe said.

Christopher gave him a look of astonishment and outrage. ‘What did you say?’

‘It’s a Judas tree,’ Sharpe said.

Christopher still looked outraged, then Sergeant Harper chimed in. ‘It’s not a cherry, sir. It’s a Judas tree. The same kind that Iscariot used to hang himself on, sir, after he betrayed our Lord.’

Christopher still gazed at Sharpe, then seemed to realize that no slur had been intended. ‘So it’s not a cherry tree, eh?’ he said, then licked the point of his pencil. ‘You are hereby ordered’ – he spoke as he wrote – ‘to return south of the river forthwith – note that, Sharpe, forthwith – and report for duty to Captain Hogan of the Royal Engineers. Signed, Lieutenant Colonel James Christopher, on the forenoon of Wednesday, March the 29th in the year of our Lord, 1809.’ He signed the order with a flourish, tore the page from the book, folded it in half and handed it to Sharpe. ‘I always thought thirty pieces of silver was a remarkably cheap price for the most famous betrayal in history. He probably hanged himself out of shame. Now go,’ he said grandly, ‘and “stand not upon the order of your going”?’ He saw Sharpe’s puzzlement, ‘Macbeth, Lieutenant,’ he explained as he spurred his horse towards the gate, ‘a play by Shakespeare. And I really would urge haste upon you, Lieutenant,’ Christopher called back, ‘for the enemy will be here any moment.’

In that, at least, he was right. A great spume of dust and smoke was boiling out from the central redoubts of the city’s northern defences. That was where the Portuguese had been putting up the strongest resistance, but the French artillery had managed to throw down the parapets and now their infantry assaulted the bastions, and the majority of the city’s defenders were fleeing. Sharpe watched Christopher and his servant gallop through the fugitives and turn into a street that led eastwards. Christopher was not retreating south, but going to the rescue of the missing Savage girl, though it would be a close-run thing if he were to escape the city before the French entered it. ‘All right, lads,’ Sharpe called, ‘time to bloody scarper. Sergeant! At the double! Down to the bridge!’

‘About bloody time,’ Williamson grumbled. Sharpe pretended not to have heard. He tended to ignore a lot of Williamson’s comments, thinking the man might improve but knowing that the longer he did nothing the more violent would be the solution. He just hoped Williamson knew the same thing.

‘Two files!’ Harper shouted. ‘Stay together!’

A cannonball rumbled above them as they ran out of the front garden and turned down the steep road that led to the Douro. The road was crowded with refugees, both civilian and military, all fleeing for the safety of the river’s southern bank, though Sharpe guessed the French would also be crossing the river within a day or two so the safety was probably illusory. The Portuguese army was falling back towards Coimbra or even all the way to Lisbon where Cradock had sixteen thousand British troops that some politicians in London wanted brought home. What use, they asked, was such a small British force against the mighty armies of France? Marshal Soult was conquering Portugal and two more French armies were just across the eastern frontier in Spain. Fight or flee? No one knew what the British would do, but the rumour that Sir Arthur Wellesley was being sent back to take over from Cradock suggested to Sharpe that the British meant to fight and Sharpe prayed the rumour was true. He had fought across India under Sir Arthur’s command, had been with him in Copenhagen and then at Rolica and Vimeiro and Sharpe reckoned there was no finer General in Europe.

Sharpe was halfway down the hill now. His pack, haversack, rifle, cartridge box and sword scabbard bounced and banged as he ran. Few officers carried a longarm, but Sharpe had once served in the ranks and he felt uncomfortable without the rifle on his shoulder. Harper lost his balance, flailing wildly because the new nails on his boot soles kept slipping on patches of stone. The river was visible between the buildings. The Douro, sliding towards the nearby sea, was as wide as the Thames at London, but, unlike London, the river here ran between great hills. The city of Oporto was on the steep northern hill while Vila Nova de Gaia was on the southern, and it was in Vila Nova that most of the British had their houses. Only the very oldest families, like the Savages, lived on the northern bank and all the port was made on the southern side in the lodges owned by Croft, Savages, Taylor Fladgate, Burmester, Smith Woodhouse and Gould, nearly all of which were British owned and their exports contributed hugely to Portugal’s exchequer, but now the French were coming and, on the heights of Vila Nova, overlooking the river, the Portuguese army had lined a dozen cannon on a convent’s terrace. The gunners saw the French appear on the opposite hill and the cannon slammed back, their trails gouging up the terrace’s flagstones. The round shots banged overhead, their sound as loud and hollow as thunder. Powder smoke drifted slowly inland, obscuring the white-painted convent as the cannonballs smashed into the higher houses. Harper lost his footing again, this time falling. ‘Bloody boots,’ he said, picking up his rifle. The other riflemen had been slowed by the press of fugitives.

‘Jesus.’ Rifleman Pendleton, the youngest in the company, was the first to see what was happening at the river and his eyes widened as he stared at the throng of men, women, children and livestock that was crammed onto the narrow pontoon bridge. When Captain Hogan had led Sharpe and his men north across the bridge at dawn there had been only a few people going the other way, but now the bridge’s roadway was filled and the crowd could only go at the pace of the slowest, and still more people and animals were trying to force their way onto the northern end. ‘How the hell do we get across, sir?’ Pendleton asked.

Sharpe had no answer for that. ‘Just keep going!’ he said and led his men down an alley that ran like a narrow stone staircase towards a lower street. A goat clattered ahead of him on sharp hooves, trailing a broken rope from around its neck. A Portuguese soldier was lying drunk at the bottom of the alley, his musket beside him and a wineskin on his chest. Sharpe, knowing his men would stop to drink the wine, kicked the skin onto the cobbles and stamped on it so that the leather burst. The streets became narrower and more crowded as they neared the river, the houses here were taller and mingled with workshops and warehouses. A wheelwright was nailing boards over his doorway, a precaution that would only annoy the French who would doubtless repay the man by destroying his tools. A red painted shutter banged in the west wind. Abandoned washing was strung to dry between the high houses. A round shot crashed through tiles, splintering rafters and cascading shards into the street. A dog, its hip cut to the bone by a falling tile, limped downhill and whined pitifully. A woman shrieked for a lost child. A line of orphans, all in dull white jerkins like farm labourers’ smocks, were crying in terror as two nuns tried to make a passage for them. A priest ran from a church with a massive silver cross on one shoulder and a pile of embroidered vestments on the other. It would be Easter in four days, Sharpe thought.

‘Use your rifle butts!’ Harper shouted, encouraging the riflemen to force their way through the crowd that blocked the narrow arched gateway leading onto the wharf. A cart loaded with furniture had spilled in the roadway and Sharpe ordered his men to pull it aside to make more space. A spinet, or perhaps it was a harpsichord, was being trampled underfoot, the delicate inlay of its cabinet shattering into scraps. Some of Sharpe’s men were pushing the orphans towards the bridge, using their rifles to hold back the adults. A pile of baskets tumbled and dozens of live eels slithered across the cobbles. French gunners had got their artillery into the upper city and now unlimbered to return the fire of the big Portuguese battery arrayed on the convent’s terrace across the valley.

Hagman shouted a warning as three blue-coated soldiers appeared from an alley, and a dozen rifles swung towards the threat, but Sharpe yelled at the men to lower their guns. ‘They’re Portuguese!’ he shouted, recognizing the high-fronted shakoes. ‘And lower your flints,’ he ordered, not wanting one of the rifles to accidentally fire in the press of refugees. A drunk woman reeled from a tavern door and tried to embrace one of the Portuguese soldiers and Sharpe, glancing back because of the soldier’s protest, saw two of his men, Williamson and Tarrant, vanish through the tavern door. It would be bloody Williamson, he thought, and shouted to Harper to keep going, then followed the two men into the tavern. Tarrant turned to defy him, but he was much too slow and Sharpe banged him in the belly with a fist, cracked both men’s heads together, punched Williamson in the throat and slapped Tarrant’s face before dragging both men back to the street. He had not said a word and still did not speak to them as he booted them towards the arch.

And once through the arch the press of refugees was even greater as the crews of some thirty British merchant ships, trapped in the city by an obstinate west wind, tried to escape. The sailors had waited until the last moment, praying that the winds would change, but now they abandoned their craft. The lucky ones used their ships’ tenders to row across the Douro, the unlucky joined the chaotic struggle to get onto the bridge. ‘This way!’ Sharpe led his men along the arched facade of warehouses, struggling along the back of the crowd, hoping to get closer to the bridge. Cannonballs rumbled high overhead. The Portuguese battery was wreathed in smoke and every few seconds that smoke became thicker as a gun fired and there would be a glow of sudden red inside the cloud, a jet of dirty smoke would billow far across the river’s high chasm and the thunderous sound of a cannonball would boom overhead as the shot or shell streaked towards the French.

A pile of empty fish crates gave Sharpe a platform from which he could see the bridge and judge how long before his men could cross safely. He knew there was not much time. More and more Portuguese soldiers were flooding down the steep streets and the French could not be far behind them. He could hear the crackle of musketry like a descant to the big guns’ thunder. He stared over the crowd’s head and saw that Mrs Savage’s coach had made it to the south bank, but she had not used the bridge, instead crossing the river on a cumbrous wine barge. Other barges still crossed the river, but they were manned by armed men who only took passengers willing to pay. Sharpe knew he could force a passage on one of those boats if he could only get near the quayside, but to do that he would need to fight through a throng of women and children.

He reckoned the bridge might make an easier escape route. It consisted of a plank roadway laid across eighteen big wine barges that were firmly anchored against the river’s current and against the big surge of tides from the nearby ocean, but the roadway was now crammed with panicked refugees who became even more frantic as the first French cannonballs splashed into the river. Sharpe, turning to look up the hill, saw the green coats of French cavalry appearing beneath the great smoke of the French guns while the blue jackets of French infantry showed in the alleyways lower down the hill.

‘God save Ireland,’ Patrick Harper said, and Sharpe, knowing that the Irish Sergeant only used that prayer when things were desperate, looked back to the river to see what had caused the three words.

He looked and he stared and he knew they were not going to cross the river by the bridge. No one was, not now, because a disaster was happening. ‘Sweet Jesus,’ Sharpe said softly, ‘sweet Jesus.’

In the middle of the river, halfway across the bridge, the Portuguese engineers had inserted a drawbridge so that wine barges and other small craft could go upriver. The drawbridge spanned the widest gap between any of the pontoons and it was built of heavy oak beams overlaid with oak planks and it was drawn upwards by a pair of windlasses that hauled on ropes through pulleys mounted on a pair of thick timber posts stoutly buttressed with iron struts. The whole mechanism was ponderously heavy and the drawbridge span was wide and the engineers, mindful of the contraption’s weight, had posted notices at either end of the bridge decreeing that only one wagon, carriage or gun team could use the drawbridge at any one time, but now the roadway was so crowded with refugees that the two pontoons supporting the drawbridge’s heavy span were sinking under the weight. The pontoons, like all ships, leaked, and there should have been men aboard to pump out their bilges, but those men had fled with the rest and the weight of the crowd and the slow leaking of the barges meant that the bridge inched lower and lower until the central pontoons, both of them massive barges, were entirely under water and the fast-flowing river began to break and fret against the roadway’s edge. The people there screamed and some of them froze and still more folk pushed on from the northern bank, and then the central part of the roadway slowly dipped beneath the grey water as the people behind forced more fugitives onto the vanished drawbridge which sank even lower.

‘Oh Jesus,’ Sharpe said. He could see the first people being swept away. He could hear the shrieks.

‘God save Ireland,’ Harper said again and made the sign of the cross.

The central hundred feet of the bridge were now under water. Those hundred feet had been swept clear of people, but more were being forced into the gap that suddenly churned white as the drawbridge was sheared away from the rest of the bridge by the river’s pressure. The great span of the bridge reared up black, turned over and was swept seawards, and now there was no bridge across the Douro, but the people on the northern bank still did not know the roadway was cut and so they kept pushing and bullying their way onto the sagging bridge and those in front could not hold them back and instead were inexorably pushed into the broken gap where the white water seethed on the bridge’s shattered ends. The cries of the crowd grew louder, and the sound only increased the panic so that more and more people struggled towards the place where the refugees drowned. Gun smoke, driven by an errant gust of wind, dipped into the gorge and whirled above the bridge’s broken centre where desperate people thrashed at the water as they were swept downstream. Gulls screamed and wheeled. Some Portuguese troops were now trying to hold the French in the streets of the city, but it was a hopeless endeavour. They were outnumbered, the enemy had the high ground, and more and more French forces were coming down the hill. The screams of the fugitives on the bridge were like the sound of the doomed on the Day of Judgment, the cannonballs were booming overhead, the streets of the city were ringing with musket shots, hooves were echoing from house walls and flames were crackling in buildings broken apart by cannon fire.

‘Those wee children,’ Harper said, ‘God help them.’ The orphans, in their dun uniforms, were being pushed into the river. ‘There’s got to be a bloody boat!’

But the men manning the barges had rowed themselves to the south bank and abandoned their craft and so there were no boats to rescue the drowning, just horror in a cold grey river and a line of small heads being swept downstream in the fretting waves and there was nothing Sharpe could do. He could not reach the bridge and though he shouted at folk to abandon the crossing they did not understand English. Musket balls were flecking the river now and some were striking the fugitives on the broken bridge.

‘What the hell can we do?’ Harper asked.

‘Nothing,’ Sharpe said harshly, ‘except get out of here.’ He turned his back on the dying crowd and led his men eastwards down the river wharf. Scores of other people were doing the same thing, gambling that the French would not yet have captured the city’s inland suburbs. The sound of musketry was constant in the streets and the Portuguese guns across the river were now firing at the French in the lower streets so that the hammering of the big guns was punctuated by the noise of breaking masonry and splintering rafters.

Sharpe paused where the wharf ended to make sure all his men were there and he looked back at the bridge to see that so many folk had been forced off its end that the bodies were now jammed in the gap and the water was piling up behind them and foaming white across their heads. He saw a blue-coated Portuguese soldier step on those heads to reach the barge on which the drawbridge had been mounted. Others followed him, skipping over the drowning and the dead. Sharpe was far enough away that he could no longer hear the screams.

‘What happened?’ Dodd, usually the quietest of Sharpe’s men, asked.

‘God was looking the other way,’ Sharpe said and looked at Harper. ‘All here?’

‘All present, sir,’ Harper said. The big Ulsterman looked as if he had been weeping. ‘Those poor wee children,’ he said resentfully.

‘There was nothing we could do,’ Sharpe said curtly, and that was true, though the truth of it did not make him feel any better. ‘Williamson and Tarrant are on a charge,’ he told Harper.

‘Again?’

‘Again,’ Sharpe said, and wondered at the idiocy of the two men who would rather have snatched a drink than escape from the city, even if that drink had meant imprisonment in France. ‘Now come on!’ He followed the civilian fugitives who, arriving at the place where the river’s wharf was blocked by the ancient city wall, had turned up an alleyway. The old wall had been built when men fought in armour and shot at each other with crossbows, and the lichen-covered stones would not have stood two minutes against a modern cannon and as if to mark that redundancy the city had knocked great holes in the old ramparts. Sharpe led his men through one such gap, crossed the remnants of a ditch and then hurried into the wider streets of the new town beyond the walls.

‘Crapauds!’ Hagman warned Sharpe. ‘Sir! Up the hill!’

Sharpe looked to his left and saw a troop of French cavalry riding to cut off the fugitives. They were dragoons, fifty or more of them in their green coats and all carrying straight swords and short carbines. They wore brass helmets that, in wartime, were covered by cloth so the polished metal would not reflect the sunlight. ‘Keep running!’ Sharpe shouted. The dragoons had not spotted the riflemen or, if they had, were not seeking a confrontation, but instead spurred on to where the road skirted a great hill that was topped with a huge white flat-roofed building. A school, perhaps, or a hospital. The main road ran north of the hill, but another went to the south, between the hill and the river, and the dragoons were on the bigger road so Sharpe kept to his right, hoping to escape by the smaller track on the Douro’s bank, but the dragoons at last saw him and drove their horses across the shoulder of the hill to block the lesser road where it bordered the river. Sharpe looked back and saw French infantry following the cavalry. Damn them. Then he saw that still more French troops were pursuing him from the broken city wall. He could probably outrun the infantry, but the dragoons were already ahead of him and the first of them were dismounting and making a barricade across the road. The folk fleeing the city were being headed off and some were climbing to the big white building while others, in despair, were going back to their houses. The cannon were fighting their own battle above the river, the French guns trying to match the bombardment from the big Portuguese battery which had started dozens of fires in the fallen city as the round shot smashed ovens, hearths and forges. The dark smoke of the burning buildings mingled with the grey-white smoke of the guns and beneath that smoke, in the valley of drowning children, Richard Sharpe was trapped.

Lieutenant Colonel James Christopher was neither a lieutenant nor a colonel, though he had once served as a captain in the Lincolnshire Fencibles and still held that commission. He had been christened James Augustus Meredith Christopher and throughout his schooldays had been known as Jam. His father had been a doctor in the small town of Saxilby, a profession and a place that James Christopher liked to ignore, preferring to remember that his mother was second cousin to the Earl of Rochford, and it was Rochford’s influence that had taken Christopher from Cambridge University to the Foreign Office where his command of languages, his natural suavity and his quick intelligence had ensured a swift rise. He had been given early responsibilities, introduced to great men and entrusted with confidences. He was reckoned to be a good prospect, a sound young man whose judgment was usually reliable, which meant, as often as not, that he merely agreed with his superiors, but the reputation had led to his present appointment which was a position as lonely as it was secret. James Christopher’s task was to advise the government whether it would be prudent to keep British troops in Portugal.