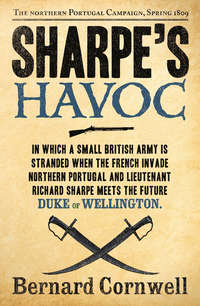

Sharpe’s Havoc: The Northern Portugal Campaign, Spring 1809

Christopher saw his hesitation. ‘If we are to persuade the British authorities that your plans are worth supporting,’ he said, ‘then we must give them names. We must. And you must trust us, my friend.’ Christopher placed a hand over his heart. ‘I swear to you upon my honour that I shall never betray those names. Never!’

Argenton, reassured, listed the men who would lead the revolt against Soult. There was Colonel Lafitte, the commanding officer of his own regiment, and the Colonel’s brother, and they were supported by Colonel Donadieu of the 47th Regiment of the Line. ‘They are respected,’ Argenton said earnestly, ‘and the men will follow them.’ He gave more names that Christopher jotted down in his notebook, but he observed that none of the mutineers was above the rank of colonel.

‘An impressive list,’ Christopher lied, then he smiled. ‘Now give me another name. Tell me who in your army would be your most dangerous opponent.’

‘Our most dangerous opponent?’ Argenton was puzzled by the question.

‘Other than Marshal Soult, of course,’ Christopher went on. ‘I want to know who we should watch. Who, perhaps, we might want to, how can I put it? Render safe?’

‘Ah.’ Argenton understood now and he thought for a short while. ‘Probably Brigadier Vuillard,’ he said.

‘I’ve not heard of him.’

‘A Bonapartiste through and through,’ Argenton said disapprovingly.

‘Spell his name for me, will you?’ Christopher asked, then wrote it down: Brigadier Henri Vuillard. ‘I assume he knows nothing of your scheme?’ he continued.

‘Of course not!’ Argenton said. ‘But it is a scheme, Colonel, that cannot work without British support. General Cradock is sympathetic, is he not?’

‘Cradock is sympathetic,’ Christopher said confidently. He had reported his earlier conversations to the British General who had seen in the proposed mutiny an alternative to fighting the French and so had encouraged Christopher to pursue the matter. ‘But alas,’ Christopher went on, ‘it’s rumoured he will soon be replaced.’

‘And the new man?’ Argenton enquired.

‘Wellesley,’ Christopher said flatly. ‘Sir Arthur Wellesley.’

‘Is he a good general?’

Christopher shrugged. ‘He’s well connected. Younger son of an earl. Eton, of course. He wasn’t thought clever enough for anything except the army, but most people think he did well near Lisbon last year.’

‘Against Laborde and Junot!’ Argenton said scathingly.

‘And he had some successes in India before that,’ Christopher added in warning.

‘Oh, in India!’ Argenton said, smiling. ‘Reputations made in India rarely stand up to a volley in Europe. But will this Wellesley want to fight Soult?’

Christopher thought about that question. ‘I think,’ he said eventually, ‘that he would prefer not to lose. I think,’ he went on, ‘that if he knows the strength of your sentiments, then he will cooperate.’ Christopher was not nearly as certain as he sounded; indeed he had heard that General Wellesley was a cold man who might not look kindly on an escapade that depended for its success on so many assumptions, but Christopher had other fish to fry in this unholy tangle. He doubted whether the mutiny could ever succeed and did not much care what Cradock or Wellesley thought of it, but knew his knowledge of it could be used to great advantage and, for the moment anyway, it was important that Argenton saw Christopher as an ally. ‘Tell me,’ he said to the Frenchman, ‘exactly what you want of us.’

‘Britain’s influence,’ Argenton said. ‘We want Britain to persuade the Portuguese leaders to accept Soult as their king.’

‘I thought you’d found plenty of support already,’ Christopher said.

‘I’ve found support,’ Argenton confirmed, ‘but most won’t declare themselves for fear of the mob’s vengeance. But if Britain encourages them they’ll find their courage. They don’t even have to make their support public, merely write letters to Soult. And then there are the intellectuals’ – Argenton’s sneer as he said the last word would have soured milk – ‘most of whom will back anyone other than their own government, but again they need encouragement before they’ll find the bravery to express support for Marshal Soult.’

‘I’m sure we would be happy to provide encouragement,’ Christopher said. He was not sure at all.

‘And we need an assurance,’ Argenton said firmly, ‘that if we lead a rebellion the British will not take advantage of the situation by attacking us. I shall want your General’s word on that.’

Christopher nodded. ‘And I think he will give it,’ he said, ‘but before he commits himself to any such promise he will want to judge for himself the likelihood of your success and that, my friend, means he will want to hear from you directly.’ Christopher unstoppered a decanter of wine, then paused before pouring. ‘And I think you need to hear his personal assurances. I think you must travel south to see him.’

Argenton looked rather surprised by this suggestion, but he thought about it for a moment and then nodded. ‘You can give me a pass that will see me safe through the British lines?’

‘I will do better, my friend. I shall come with you so long as you provide me with a pass for the French lines.’

‘Then we shall go!’ Argenton said happily. ‘My Colonel will give me permission, once he understands what we are doing. But when? Soon, I think, don’t you? Tomorrow?’

‘The day after tomorrow,’ Christopher said firmly. ‘I have an engagement tomorrow that I cannot avoid, but if you join me in Vila Real de Zedes tomorrow afternoon then we can travel the next day. Will that suit?’

Argenton nodded. ‘You must tell me how to reach Vila Real de Zedes.’

‘I shall give you directions,’ Christopher said, then raised his glass, ‘and I shall drink to the success of our endeavours.’

‘Amen to that,’ Argenton said, and raised his glass to the toast.

And Colonel Christopher smiled, because he was rewriting the rules.

CHAPTER THREE

Sharpe ran across the paddock where the dead horses lay with flies crawling in their nostrils and across their eyeballs. He tripped on a metal picketing pin and, as he stumbled forward, a carbine bullet fluttered past him, the sound suggesting it was almost spent, but even a spent bullet in the wrong place could kill a man. His riflemen were shooting from the field’s far side, the smoke of their Baker rifles thickening along the wall. Sharpe dropped beside Hagman. ‘What’s happening, Dan?’

‘Dragoons are back, sir,’ Hagman said laconically, ‘and there’s some infantry there too.’

‘You sure?’

‘Shot one blue bastard,’ Hagman said, ‘and two greens so far.’

Sharpe wiped sweat from his face, then crawled a few paces along the wall to a place where the powder smoke was not so thick. The dragoons had dismounted and were shooting from the edge of a wood some hundred paces away. Too long a range for their carbines, Sharpe thought, but then he saw some blue uniforms where the road ran through the trees and he reckoned the infantry was forming for an attack. There was an odd clicking noise coming from somewhere nearby and he could not place it, but it seemed to offer no threat so he ignored it. ‘Pendleton!’

‘Sir?’

‘Find Lieutenant Vicente. He’s in the village. Tell him to get his men out on the northern path now.’ Sharpe pointed to the track through the vineyards, the same track by which they had entered Barca d’Avintas and where the dead dragoons of the first fight still lay. ‘And, Pendleton, tell him to hurry. But be polite, though.’

Pendleton, a pickpocket and purse snatcher from Bristol, was the youngest of Sharpe’s men and now looked puzzled. ‘Polite, sir?’

‘Call him sir, damn you, and salute him, but hurry!’

Goddamn it, Sharpe thought, but there would be no escape across the Douro today, no slow shuttling back and forth with the small boat, and no marching back to Captain Hogan and the army. Instead they would have to get the hell out northwards and get out fast. ‘Sergeant!’ He looked left and right for Patrick Harper through the misty patches of rifle smoke along the wall. ‘Harper!’

‘I’m with you, sir.’ Harper came running from behind. ‘I was dealing with those two Frogs in the church.’

‘The moment the Portuguese are into the vineyard we get out of here. Are any of our men left in the village?’

‘Harris is there, sir, and Pendleton, of course.’

‘Send someone to make sure the two of them get out.’ Sharpe levelled his rifle across the wall and sent a bullet spinning towards the infantry who were forming up on the road among the trees. ‘And, Pat, what did you do with those two Frogs?’

‘They’d robbed the poor box,’ Harper said, ‘so I sent them to hell.’ He patted his sheathed sword bayonet.

Sharpe grinned. ‘And if you get the chance, Pat, do the same to that bastard French officer.’

‘Pleasure, sir,’ Harper said, then ran back across the paddock. Sharpe reloaded. The French, he thought, were being too cautious. They should have attacked already, but they must have believed there was a larger force in Barca d’Avintas than two stranded half companies, and the rifle fire must have been disconcerting to the dragoons who were not used to such accuracy. There were bodies lying on the grass at the edge of the wood, evidence that the dismounted French horsemen had been taught about the Baker rifle the hard way. The French did not use rifles, reckoning that the spiralling grooves and lands that spun the bullet in the barrel and so gave the weapon its accuracy also made it much too slow to reload, and so the French, like most British battalions, relied on the quicker-firing, but much less accurate musket. A man could stand fifty yards from a musket and stand a good chance of living, but standing a hundred paces in front of a Baker in the hands of a good man was a death warrant, and so the dragoons had pulled back into the trees.

There was infantry in the wood as well, but what were the bastards doing? Sharpe propped his loaded rifle against the wall and took out his telescope, the fine instrument made by Matthew Berge of London which had been a gift from Sir Arthur Wellesley after Sharpe had saved the General’s life at Assaye. He rested the telescope on the wall’s mossy coping and stared at the leading company of French infantry which was well back in the trees, but Sharpe could see they were formed in three ranks. He was looking for some sign that they were ready to advance, but the men were slouching, musket butts grounded, without even fixed bayonets. He whipped the glass right, suddenly fearing that perhaps the French would try to cut off his retreat by infiltrating the vineyard, but he saw nothing to worry him. He looked back at the trees and saw a flash of light, a distinct white circle, and realized there was an officer kneeling in the leafy shadows staring at the village through a telescope. The man was undoubtedly trying to work out how many enemy were in Barca d’Avintas and how to attack them. Sharpe put his own telescope away, picked up the rifle and levelled it on the wall. Careful now, he thought, careful. Kill that one officer and any French attack is slowed, because that officer is the man who makes the decisions, and Sharpe pulled back the flint, lowered his head so that his right eye was gazing down the sights, found the patch of dark shadow that was the Frenchman’s blue coat and then raised the rifle’s foresight, a blade of metal, so that the barrel hid the target and so allowed the bullet to drop. There was little wind, not enough to drift the bullet left or right. A splintering of noise sounded from the other rifles and a drop of sweat trickled past Sharpe’s left eye as he pulled the trigger and the rifle hammered back into his shoulder and the puff of bitter smoke from the pan made his right eye smart and the specks of burning powder stung his cheek as the cloud of barrel smoke billowed in front of the wall to hide the target. Sharpe twisted to see Lieutenant Vicente’s troops streaming into the vineyard accompanied by thirty or forty civilians. Harper was coming back across the paddock. The odd clicking noise was louder suddenly and Sharpe registered that it was the sound of French carbine bullets striking the other side of the stone wall. ‘We’re all clear of the village, sir,’ Harper said.

‘We can go,’ Sharpe said, and he marvelled that the enemy had been so slow, thus giving him time to extricate his force. He sent Harper with most of the greenjackets to join Vicente and they took a dozen French horses with them, each horse worth a small fortune in prize money if they could ever rejoin the army. Sharpe kept Hagman and six other men and they spread along the wall and fired as fast as their rifles would load, which meant they did not wrap the bullets in leather patches which gripped the rifling, but just tapped the balls down the barrels because Sharpe did not care about accuracy, he just wanted the French to see a thick rill of smoke and hear the shots and thus not know that their enemy was withdrawing.

He pulled the trigger and the flint broke into useless scraps so he slung the rifle and backed out of the smoke to see that Vicente and Harper were both well into the vineyard and so he shouted at his remaining men to hurry back across the paddock. Hagman paused to fire a last bullet, then he ran and Sharpe went with him, the last man to leave, and he could not believe it had been that easy to disengage, that the French had been so supine, and just then Hagman went down.

At first Sharpe thought Hagman had tripped on one of the metal pegs with which the dragoons had picketed their horses, then he saw blood on the grass and saw Hagman let go of his rifle and his right hand slowly clench and unclench. ‘Dan!’ Sharpe knelt and saw a tiny wound high up beside Hagman’s left shoulder blade, just an unlucky carbine bullet that had flicked through the smoke and found its target.

‘Go on, sir.’ Hagman’s voice was hoarse. ‘I’m done for.’

‘You’re bloody not,’ Sharpe snarled and he turned Hagman over onto his back and saw no wound in front, which meant the carbine ball was somewhere inside, then Hagman choked and spat up frothy blood and Sharpe heard Harper yelling at him.

‘The bastards are coming, sir!’

Just one minute before, Sharpe thought, he had been congratulating himself on how easy it had been, and now it was all collapsing. He pulled Hagman’s rifle to him, slung it beside his own and picked up the old poacher who gave a gasp and a whimper and shook his head. ‘Leave me, sir.’

‘I’m not leaving you, Dan.’

‘Hurts, sir, it hurts,’ Hagman whimpered again. His face was deathly pale and there was a trickle of blood spilling from his mouth, and then Harper was at Sharpe’s side and took Hagman out of his arms. ‘Leave me here,’ Hagman said softly.

‘Take him, Pat!’ Sharpe said, and then some rifles fired from the vineyard and muskets banged behind him and the air was whistling with balls as Sharpe pushed Harper on. He followed, walking backwards, watching the blue French uniforms appear in the mist of smoke left by their own ragged volley.

‘Come on, sir!’ Harper shouted, letting Sharpe know he had Hagman in the scanty shelter of the vines.

‘Carry him north,’ Sharpe said when he reached the vineyard.

‘He’s hurting bad, sir.’

‘Carry him! Get him out of here.’

Sharpe watched the French. Three companies of infantry had attacked the pasture, but they made no effort to follow Sharpe north. They must have seen the column of Portuguese and British troops winding through the vineyards accompanied by the dozen captured horses and a crowd of frightened villagers, but they did not follow. It seemed they wanted Barca d’Avintas more than they wanted Sharpe’s men dead. Even when Sharpe established himself on a knoll a half-mile north of the village and stared at the French through his telescope, they did not come near to threaten him. They could easily have chased him away with dragoons, but instead they chopped up the skiff that Sharpe had rescued and then set the fragments alight. ‘They’re closing off the river,’ Sharpe said to Vicente.

‘Closing the river?’ Vicente did not understand.

‘Making sure they’ve got the only boats. They don’t want British or Portuguese troops crossing the river, attacking them in the rear. Which means it’s going to be bloody hard for us to go the other way.’ Sharpe turned as Harper came near, and saw that the big Irish Sergeant’s hands were bloody. ‘How is he?’

Harper shook his head. ‘He’s in a terrible bad way, sir,’ he said gloomily. ‘I think the bloody ball’s in his lung. Coughing red bubbles he is, when he can cough at all. Poor Dan.’

‘I’m not leaving him,’ Sharpe said obstinately. He knew he had left Tarrant behind, and there were men like Williamson who had been friends of Tarrant who would resent that Sharpe was not doing the same with Hagman, but Tarrant had been a drunk and a troublemaker while Dan Hagman was valuable. He was the oldest man among Sharpe’s riflemen and he had a wealth of common sense that made him a steadying influence. Besides, Sharpe liked the old poacher. ‘Make a stretcher, Pat,’ he said, ‘and carry him.’

They made a stretcher out of jackets that had their sleeves threaded onto two poles cut from an ash tree and while it was being fashioned Sharpe and Vicente watched the French and discussed how they were to escape them. ‘What we must do,’ the Portuguese Lieutenant said, ‘is go east. To Amarante.’ He smoothed a patch of bare earth and scratched a crude map with a splinter of wood. ‘This is the Douro,’ he said, ‘and here is Porto. We are here’ – he tapped the river very close to the city – ‘and the nearest bridge is at Amarante.’ He made a cross mark well to the east. ‘We could be there tomorrow or perhaps the day after.’

‘So can they,’ Sharpe said grimly, and he nodded towards the village.

A gun had just appeared from among the trees where the French had waited so long before attacking Sharpe’s men. The cannon was drawn by six horses, three of which were ridden by gunners in their dark-blue uniforms. The gun itself, a twelve-pounder, was attached to its limber which was a light two-wheeled cart that served as a ready magazine and as an axle for the heavy gun’s trail. Behind the gun was another team of four horses, these pulling a coffin-like caisson that carried a spare gun wheel on its stern. The caisson, which was being ridden by a half-dozen gunners, held the cannon’s ammunition. Even from half a mile away Sharpe could hear the clink of the chains and thump of the wheels. He watched in silence as an howitzer came into sight, then a second twelve-pounder, and after that a troop of hussars.

‘Do you think they’re coming here?’ Vicente asked with alarm.

‘No,’ Sharpe said. ‘They’re not interested in fugitives. They’re going to Amarante.’

‘This is not the good road to Amarante. In fact it goes nowhere. They’ll have to strike north to the main road.’

‘They don’t know that yet,’ Sharpe guessed, ‘they’re taking any road east that they can find.’ Infantry had now appeared from the trees, then another battery of artillery. Sharpe was watching a small army march eastwards and there was only one reason to send so many men and guns to the east and that was to capture the bridge at Amarante and so protect the French left flank. ‘Amarante,’ Sharpe said, ‘that’s where the bastards are going.’

‘Then we can’t,’ Vicente said.

‘We can go,’ Sharpe said, ‘we just can’t go on that road. You say there’s a main road?’

‘Up here,’ Vicente said, and scratched the earth to show another road to the north of them. ‘That is the high road,’ Vicente said. ‘The French are probably on that as well. Do you really have to go to Amarante?’

‘I’ve got to cross the river,’ Sharpe said, ‘and there’s a bridge there, and there’s a Portuguese army there, and just because the bloody Frogs are going there doesn’t mean that they’ll capture the bridge.’ And if they did, he thought, then he could go north from Amarante until he found a crossing place, then follow the Tamega’s far bank south until he reached a stretch of the Douro unguarded by the French. ‘So how do we reach Amarante if we don’t go by road? Can we go across country?’

Vicente nodded. ‘We go north to a village here’ – he pointed to an empty space on his map – ‘and then turn east. The village is on the edge of the hills, the beginning of the – what do you call it? The wilderness. We used to go there.’

‘We?’ Sharpe asked. ‘The poets and philosophers?’

‘We would walk there,’ Vicente said, ‘spend the night in the tavern and walk back. I doubt there will be Frenchmen there. It is not on the road to Amarante. Not on any road.’

‘So we go to the village at the edge of the wilderness,’ Sharpe said. ‘What’s it called?’

‘Vila Real de Zedes,’ Vicente said. ‘It is called that because the vineyards there once belonged to the King, but that was long ago. Now they are the property of –’

‘Vila Real de what?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Zedes,’ Vicente said, puzzled by Sharpe’s tone and even more puzzled by the smile on Sharpe’s face. ‘You know the place?’

‘I don’t know it,’ Sharpe said, ‘but there’s a girl I want to meet there.’

‘A girl!’ Vicente sounded disapproving.

‘A nineteen-year-old girl,’ Sharpe said, ‘and believe it or not, it’s a duty.’ He turned to see if the stretcher was finished and suddenly stiffened in anger. ‘What the hell is he doing here?’ he asked. He was staring at the French dragoon, Lieutenant Olivier, who was watching as Harper carefully rolled Hagman onto the stretcher.

‘He is to stand trial,’ Vicente said stubbornly, ‘so he is here under arrest and under my personal protection.’

‘Bloody hell!’ Sharpe exploded.

‘It is a matter of principle,’ Vicente insisted.

‘Principle!’ Sharpe shouted. ‘It’s a matter of bloody stupidity, lawyer’s bloody stupidity! We’re in the middle of a bloody war, not in a bloody assizes town in England.’ He saw Vicente’s incomprehension. ‘Oh, never mind,’ he growled. ‘How long will it take us to reach Vila Real de Zedes?’

‘We should be there tomorrow morning,’ Vicente said coldly, then looked at Hagman, ‘so long as he doesn’t slow us down too much.’

‘We’ll be there tomorrow morning,’ Sharpe said, and then he would rescue Miss Savage and find out just why she had run away. And after that, God help him, he would slaughter the bloody dragoon officer, lawyer or no lawyer.

The Savage country house, which was called the Quinta do Zedes, was not in Vila Real de Zedes itself, but high on a hill spur to the south of the village. It was a beautiful place, its whitewashed walls edged with masonry to trace out the elegant lines of a small manor house which looked across the once royal vineyards. The shutters were painted blue, and the high windows of the ground floor were decorated with stained glass which showed the coats of arms of the family which had once owned the Quinta do Zedes. Mister Savage had bought the Quinta along with the vineyards, and, because the house was high, possessed a thick tiled roof and was surrounded by trees hung with wisteria, it proved blessedly cool in summer and so the Savage family would move there each June and stay till October when they took themselves back to the House Beautiful high on Oporto’s slope. Then Mister Savage had died of a seizure and the house had stayed empty ever since except for the half-dozen servants who lived at the back and tended the small vegetable garden and walked down the long curving drive to the village church for mass. There was a chapel in the Quinta do Zedes and in the old days, when the owners of the coats of arms had lived in the long cool rooms, the servants had been allowed to attend mass in the family chapel, but Mister Savage had been a staunch Protestant and he had ordered the altar to be taken away, the statues removed and the chapel whitewashed for use as a food store.

The servants had been surprised when Miss Kate came to the house, but they curtsied or bowed and then set about making the great rooms comfortable. The dust sheets were pulled from pieces of furniture, the bats were knocked off the beams and the pale-blue shutters were thrown open to let in the spring sun. Fires were lit to take away the lingering winter chill, though on that first evening Kate did not stay indoors beside the fires, but instead sat on a balcony built on top of the Quinta’s porch and stared down the drive which was edged with wisteria hanging from the cedar trees. The evening shadows stretched, but no one came.