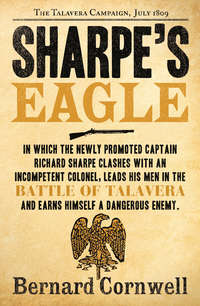

Sharpe’s Eagle: The Talavera Campaign, July 1809

But it was not just Simmerson. He looked at the road leading to the town where an indistinct group of women stood, the wives of the Battalion, and wondered whether the girl, Josefina Lacosta, was there. He had at least learned her name and seen her, a dozen times, mounted on the delicate black mare with a crowd of Simmerson’s Lieutenants laughing and joking with her. He had listened to the rumours about her; that she was the widow of a rich Portuguese officer, that she had run away from the Portuguese officer, no one seemed sure, but what was certain was that she had met Gibbons at a ball in Lisbon’s American Hotel and, within hours, had decided to go to the war with him. It was said that they planned to marry once the army reached Madrid and that Gibbons had promised her a house and a life of dancing and gaiety. Whatever the truth of Josefina there was no denying her presence, entrancing the whole Battalion, flirting even with Sir Henry who responded with a heavy gallantry and told the officers that young men would be young men. ‘Christian needs his exercise, what?’ Simmerson would repeat the joke and laugh each time. The Colonel’s indulgence reached to letting his nephew break his standing order and take a suite of rooms in the town where he lived with the girl and entertained friends in the long, warm evenings. Gibbons was the envy of all the officers, Josefina the jewel in his crown, and Sharpe shivered on the bridge and wondered if she would ever go back to the flatlands of Essex and to a big house built on the profits of salted fish.

Seven chimed and there was a stir of excitement as a group of horsemen appeared from the houses and spurred towards the waiting Battalion. The riders turned out to be British and the ranks relaxed again. Hogan and Sharpe walked back to their men paraded next to Lennox’s Light Company at the left of the Battalion and watched the newcomers ride to join Simmerson. All the riders but one were in uniform and the exception wore blue trousers under a grey cloak and on his head a plain bicorne hat. Ensign Denny, sixteen years old and full of barely suppressed excitement, was standing near the Riflemen and Sharpe asked him if he knew who the apparent civilian was.

‘No, sir.’

‘Sergeant Harper! Tell Mr Denny who the gentleman in the grey cloak is.’

‘That’s the General, Mr Denny. Sir Arthur Wellesley himself. Born in Ireland like all the best soldiers!’

A ripple of laughter went through the ranks but they all straightened up and stared at the man who would lead them towards Madrid. They saw him take out a watch and look towards the town from where the Spanish should be coming but there was still no sign of the Regimienta even though the sun was well over the horizon and the dew fading fast from the grass. One of the staff officers with Wellesley broke away from the group and trotted his horse towards Hogan. Sharpe supposed he wanted to talk to the Engineer and he walked away, back to the bridge, to give Hogan some privacy.

‘Sharpe! Richard!’

The voice was familiar, from the past. He turned to see the staff officer, a Lieutenant Colonel, waving to him but the face was hidden beneath the ornate cocked hat.

‘Richard! You’ve forgotten me!’

Lawford! Sharpe’s face broke into a smile. ‘Sir! I didn’t even know you were here!’

Lawford swung easily out of the saddle, took off his hat, and shook his head. ‘You look dreadful! You must really buy yourself a uniform one of these days.’ He smiled and shook Sharpe’s hand. ‘It’s good to see you, Richard.’

‘And to see you, sir. A Lieutenant Colonel? You’re doing well!’

‘It cost me three thousand, five hundred pounds, Richard, and well you know it. Thank God for money.’

Lawford. Sharpe remembered when the Honourable William Lawford was a frightened Lieutenant and a Sergeant called Sharpe had guided him through the heat of India. Then Lawford had repaid the debt. In a prison cell in Seringapatam the aristocrat had taught the Sergeant to read and write, the exercise had stopped them both going mad in the dank hell of the Sultan Tippoo’s dungeons. Sharpe shook his head. ‘I haven’t seen you for …’

‘It’s been months. Far too long. How are you?’

Sharpe grinned. ‘As you see me.’

‘Untidy?’ Lawford smiled. He was the same age as Sharpe but there the resemblance stopped. Lawford was a dandy, dressed always in the finest cloth and lace, and Sharpe had seen him pay a Regimental Tailor seven guineas to achieve a tighter fit on an already immaculately tailored jacket. He spread his hands expansively.

‘You can stop worrying, Richard, Lawford is here. The French will probably surrender when they hear. God! It’s taken me months to get this job! I was stuck in Dublin Castle, changing the bloody guard, and I’ve pulled a hundred strings to get on to Wellesley’s staff. And here I am! Arrived two weeks ago!’ The words tumbled out. Sharpe was delighted to see him. Lawford, like Gibbons, summed up all that he hated most about the army; how money and influence could buy promotion while others, like Sharpe, rotted in penury. Yet Sharpe liked Lawford, could feel no resentment, and he supposed that it was because the aristocrat, for all the assurance of his birth, responded to Sharpe in the same way. And Lawford, for all his finery and assumed languor, was a fighting soldier. Sharpe held up a hand to stop the flow of news.

‘What’s happening, sir? Where are the Spanish?’

Lawford shook his head. ‘Still in bed. At least they were, but the bugles have sounded, the warriors have pulled on their trousers and we’re told they’re coming.’ He leaned closer to Sharpe and dropped his voice. ‘How do you get on with Simmerson?’

‘I don’t have to get on with him. I work for Hogan.’

Lawford appeared not to hear the answer. ‘He’s an extraordinary man. Did you know he paid to raise this Regiment?’ Sharpe nodded. ‘Do you know what that cost him, Richard? Unimaginable!’

‘So he’s a rich man. But it doesn’t make him a soldier.’ Sharpe sounded sour.

Lawford shrugged. ‘He wants to be. He wants to be the best. I sailed out on the same boat and all he did, every day, was sit there reading the Rules and Regulations for His Majesty’s Forces!’ He shook his head. ‘Perhaps he’ll learn. I don’t envy you, though.’ He turned to look at Wellesley. ‘Well. I can’t stay all day. Listen. You must dine with me when you get back from this job. Will you do that?’

‘With pleasure.’

‘Good!’ Lawford swung up into the saddle. ‘You’ve got a scrap ahead of you. We sent the Light Dragoons down south and they tell us there’s a sizeable bunch of Frenchies down there with some horse artillery. They’ve been trying to flush the Guerilleros out of the hills but they’re moving back east now, like us, so good luck!’ He turned his horse away, then looked back. ‘And, Richard?’

‘Sir?’

‘Sir Arthur asked to be remembered.’

‘He did?’

Lawford looked down on Sharpe. ‘You’re an idiot.’ He spoke cheerfully. ‘Shall I remember you to the General? It’s the done thing, you know.’ He grinned, raised his hat and turned away. Sharpe watched him go, the apprehension of the cold dawn suddenly dissipated by the rush of friendship. Hogan joined him.

‘Friends in high places?’

‘Old friend. We were in India.’

Hogan said nothing. He was staring across the field, his jaw sagging in astonishment, and Sharpe followed his gaze. ‘My God.’

The Regimienta had arrived. Two trumpeters in powdered wigs led the procession. They were mounted on glossy black horses, bedecked in uniforms that were a riot of gold and silver, their trumpets festooned with ribbons, tassels, and banners.

‘Hell’s teeth.’ The voice came from the ranks. ‘The Fairies are on our side.’

The colours came next, two flags covered in armorial bearings, threaded with gold, tasselled, looped, crowned, curlicued, emblazoned, carried by horsemen whose mounts stepped delicately high as though the earth was scarcely fit to carry such splendid creations. The officers came next. They should have delighted the soul of Sir Henry Simmerson for everything that could be polished had been burnished to an eye-hurting intensity; whether of leather, or bronze, silver or gold. Epaulettes of twisted golden strands were encrusted with semi-precious stones; their coats were piped with silver threads, frogged and plumed, sashed and shining. It was a dazzling display.

The men came next, a shambling mess, rattled on to the field by energetic but erratic drummers. Sharpe was appalled. All he had heard of the Spanish army seemed to be true in the Regimienta; their weapons looked dull and uncared for, there was no spirit in their bearing, and Madrid seemed suddenly a long way off if this was the quality of the allies who would help clear the road. There was a renewed energy from the Spanish drummers as the two trumpeters challenged the sky with a resounding fanfare. Then silence.

‘Now what?’ Hogan muttered.

Speeches. Wellesley, wise in the ways of diplomacy, escaped as the Spanish Colonel came forward to harangue the South Essex. There was no official translator but Hogan, who spoke passable Spanish, told Sharpe the Colonel was offering the British a chance, a small chance, to share in the glorious triumph of the Spanish warriors over their enemy. The glorious Spanish warriors, prompted by their non-commissioned officers, cheered the speech while the South Essex, prompted by Simmerson, did the same. Salutes were exchanged, arms presented, there were more fanfares, more drums, all climaxing in the appearance of a priest who, riding a small grey donkey, blessed the Santa Maria with the help of small, white-surpliced boys. Pointedly the pagan British were not included in the pleas to the Almighty.

Hogan took out his snuff box. ‘Do you think they’ll fight?’

‘God knows.’ The year before, Sharpe knew, a Spanish army had forced the surrender of twenty thousand Frenchmen so there was no doubting that the Spaniards could fight if their leadership and organisation were equal to their ambitions. But, to Sharpe, the evidence of the Regimienta suggested that their immediate allies had neither the organisation nor the leaders to do anything except, perhaps, make bombastic speeches.

At half past ten, five hours late, the Battalion finally shrugged on its packs and followed the Santa Maria across the old bridge. Sharpe and Hogan travelled ahead of the South Essex and immediately behind a far from warlike Spanish rearguard. A bunch of mules was being coaxed along, loaded high with luxuries to keep the Spanish officers comfortable in the field, while, in the middle of the beasts, rode the priest who continually turned and smiled nervously with blackened teeth at the heathens on his tail. Strangest of all were three white-dressed young women who rode thoroughbred horses and carried fringed parasols. They giggled constantly, turned and peeped at the Riflemen, and looked incongruously like three brides on horseback. What a way, Sharpe thought, to go to war.

By midday the column had covered a mere five miles and had come to a complete stop. Trumpets sounded at the head of the Regimienta, officers galloped in urgent clouds of dust up and down the ranks, and the soldiers simply dropped their weapons and packs and sat down in the road. Anyone with any kind of rank started to argue, the priest, stuck among the mules, screamed hysterically at a mounted officer, while the three women wilted visibly and fanned themselves with their white-gloved hands. Christian Gibbons walked his horse to the head of the British column and sat staring at the three women. Sharpe looked up at him.

‘The middle one is the prettiest.’

‘Thank you.’ Gibbons spoke with a heavy irony. ‘That’s civil of you, Sharpe.’ He was about to urge his horse forward when Sharpe put a hand on the bridle.

‘Spanish officers, I hear, are very fond of duelling.’

‘Ah.’ Gibbons stared icily down on Sharpe. ‘You may have a point.’ He wheeled his horse back down the road.

Hogan was shouting at the priest, in Spanish, trying to discover why they had stopped. The priest smiled his blackened smile and raised his eyes to heaven as if to say it was all God’s will and there was nothing to be done about it.

‘Damn this!’ Hogan looked round urgently. ‘Damn! Don’t they know how much time we’ve lost? Where’s the Colonel?’

Simmerson was not far behind. He and Forrest arrived with a clatter of hooves. ‘What the devil’s happening?’

‘I don’t know, sir. Spanish have sat down.’

Simmerson licked his lips. ‘Don’t they know we’re in a hurry?’ No one spoke. The Colonel looked round the officers as though one of them might suggest an answer. ‘Come on, then. We’ll see what it’s about. Hogan, will you translate?’

Sharpe fell his men out as the mounted officers rode up the column and the Riflemen sat beside the road with their packs beside them. The Spanish appeared to be asleep. The sun was high and the road surface reflected a searing heat. Sharpe touched the muzzle of his rifle by mistake and flinched from the hot metal. Sweat trickled down his neck and the glare of the sun, reflected from the metal ornaments of the Spanish infantry, was dazzling. There were still fifteen miles to go. The three women rode their horses slowly towards the head of the Regimienta, one of them turned and waved coquettishly to the Riflemen and Harper blew her a kiss, and when they had gone the dust drifted gently on to the thin grass of the verge.

Fifteen minutes of silence passed before Simmerson, Forrest and Hogan pounded back from their meeting with the Spanish Colonel. Sir Henry was not pleased. ‘Damn them! They’ve stopped for the day!’

Sharpe looked questioningly at Hogan. The Engineer nodded. ‘It’s true. There’s an inn up there and the officers have settled in.’

‘Damn! Damn! Damn!’ Simmerson was pounding the pommel of his saddle. ‘What are we to do?’

The mounted officers glanced at each other. Simmerson was the man who had to make the decision and none of them answered his question, but there was only one thing to do. Sharpe looked at Harper.

‘Form up, Sergeant.’

Harper bellowed orders. The Spanish muleteers, their rest disturbed, looked curiously as the Riflemen pulled on their packs and formed ranks.

‘Bayonets, Sergeant.’

The order was given and the long, brass-handled sword-bayonets rasped from the scabbards. Each blade was twenty-three inches long, each sharp and brilliant in the sun. Simmerson looked nervously at the weapons. ‘What the devil are you doing, Sharpe?’

‘Only one thing to do, sir.’

Simmerson looked left and right at Forrest and Hogan, but they offered him no help. ‘Are you proposing we should simply carry on, Sharpe?’

It’s what you should have proposed, thought Sharpe, but instead he nodded. ‘Isn’t that what you intended, sir?’

Simmerson was not sure. Wellesley had impressed on him the need for speed but there was also the duty not to offend a touchy ally. But what if the bridge should already be occupied by the French? He looked at the Riflemen, grim in their dark uniforms, and then at the Spanish who lolled in the roadway smoking cigarettes. ‘Very well.’

‘Sir.’ Sharpe turned to Harper. ‘Four ranks, Sergeant.’

Harper took a deep breath. ‘Company! Double files to the right!’

There were times when Sharpe’s men, for all their tattered uniforms, knew how to startle a Militia Colonel. With a snap and a precision that would have done credit to the Guards the even numbered files stepped backwards; the whole company, without another word of command, turned to the right and instead of two ranks there were now four facing towards the Spanish. Harper had paused for a second while the movement was carried out. ‘Quick march!’

They marched. Their boots crashed on to the road scattering mules and muleteers before them. The priest took one look, kicked his heels, and the donkey bolted into the field.

‘Come on, you bastards!’ Harper shouted. ‘March as if you mean it!’

They did. They pushed their tempo up to the Light Infantry quick march and stamped with their boots so that the dust flew up. Behind them the South Essex were formed and following, before them the Regimienta split apart into the fields, the officers running from the white-walled inn and screaming at the Riflemen. Sharpe ignored them. The Spanish Colonel, a vision of golden lace, appeared at the inn doorway to see his Regiment in tatters. The men had scattered into the fields and the British were on their way to the bridge. The Colonel was without his boots and in his hand he held a glass of wine. As they drew level with the inn Sharpe turned to his men.

‘Company! To the right! Salute!’

He drew the long blade, held it in the ceremonial salute, and his men grinned as they presented their arms towards the Colonel. There was little he could do. He wanted to protest but honour was honour and the salute should be returned. The Spaniard was in a quandary. In one hand, the wine, and in the other a long cigar. Sharpe watched the debate on the Spanish Colonel’s face as he looked from one hand to the other, trying to decide which to abandon, but in the end the Colonel of the Santa Maria stood to attention in his stockings and held the wine glass and cigar at a dutifully ceremonious angle.

‘Eyes front!’

Hogan laughed out loud. ‘Well done, Sharpe!’ He looked at his watch. ‘We’ll make the bridge before nightfall. Let’s hope the French don’t.’

Let’s hope the French don’t make it at all, thought Sharpe. Defeating an ally was one thing but his doubts about the ability of the South Essex to face the French were as real as ever. He looked at the white, dusty road stretching over the featureless plain and in a fleeting, horrid moment wondered whether he would return. He pushed the thought away and gripped the stock of his rifle. With his other hand he unconsciously felt the lump over his breastbone. Harper saw the gesture. Sharpe thought it was a secret that round his neck he had a leather bag in which he kept his worldly wealth but all his men knew it was there and Sergeant Harper knew that when Sharpe touched the bag with its few gold coins looted from old battlefields then the Lieutenant was worried. And if Sharpe was worried? Harper turned to the Riflemen. ‘Come on, you bastards! This isn’t a funeral! Faster!’

CHAPTER SIX

Valdelacasa did not exist as a place where human beings lived, loved, or traded, it was simply a ruined building and a great stone bridge that had been built to span the river at a time when the Tagus was wider than the flow which now slid darkly between the three central arches of the Roman stonework. And from the bridge, with its attendant building, the land spread outwards in a vast, shallow bowl bisected by the river in one direction and the road which led to and from the bridge in the other. The Battalion had marched down the almost imperceptible incline as the shadows of dusk began to creep across the pale grasslands. There was no farming, no cattle, no sign of life; just the ancient ruin, the bridge, and the water slipping silently towards the far-off sea.

‘I don’t like it, sir.’ Harper’s face had been genuinely worried.

‘Why not?’

‘No birds, sir. Not even a vulture.’

Sharpe had to admit it was true, there was not a bird to be seen or heard. It was like a place forgotten and as they marched towards the building the men in green jackets were unnaturally quiet as if infected by some ancient gloom.

‘There’s no sign of the French.’ Sharpe could see no movement in the darkening landscape.

‘It’s not the French that worry me.’ Harper was really concerned. ‘It’s this place, sir. It’s not good.’

‘You’re being Irish, Sergeant.’

‘That may be, sir. But tell me why there’s no village here. The soil is better than the stuff we’ve marched past, there’s a bridge, so why no village?’

Why not? It seemed an obvious place for a village but on the other hand they had passed only one small hamlet in the last ten miles so it was possible that there were simply not enough people on the vast remoteness of the Estramaduran plain to inhabit every likely spot. Sharpe tried to ignore Harper’s concern but, coming as it did on top of his own gloomy presentiments, he had begun to feel that Valdelacasa really did have a sinister air about it. Hogan did not help.

‘That’s the Puente de los Malditos; the Bridge of the Accursed.’ Hogan walked his horse beside them and nodded at the building. ‘That must have been the convent. The Moors beheaded every single nun. The story goes that they were killed on the bridge, that their heads were thrown into the water but the bodies left to rot. They say no one lives here because the spirits walk the bridge at night looking for their heads.’

The Riflemen heard him in silence. When Hogan had finished Sharpe was surprised to see his huge Sergeant surreptitiously cross himself and he guessed that they would spend a restless night. He was right. The darkness was total, there was no wood on the plain so the men could build no fires, and in the small hours a wind brought clouds that covered the moon. The Riflemen were guarding the southern end of the bridge, the bank on which the French were loose, and it was a nervous night as shadows played tricks and the chill sentries were not certain whether they imagined the noises that could either be headless nuns or patrolling Frenchmen. Just before dawn Sharpe heard the sound of a bird’s wings, followed by the call of an owl, and he wondered whether to tell Harper that there were birds after all. He decided not; he remembered that owls were supposed to be harbingers of death and the news might worry the Irishman even more.

But the new day, even if it did not bring the Regimienta who were presumably still at the inn, brought a brilliant blue sky with only a scattering of high, passing clouds that followed the night’s belt of light rain. Harsh ringing blows came from the bridge where Hogan’s artificers hammered down the parapet at the spot chosen for the explosion and the apprehensions of the night seemed, for the moment, to be like a bad dream. The Riflemen were relieved by Lennox’s Light Company and, with nothing else to do, Harper stripped naked and waded into the river.

‘That’s better. I haven’t washed in a month.’ He looked up at Sharpe. ‘Is anything happening, sir?’

‘No sign of them.’ Sharpe must have stared at the horizon, a mile to the south, fifty times since dawn but there had been no sign of the French. He watched as Harper came dripping wet out of the river and shook himself like a wolfhound. ‘Perhaps they’re not here, sir.’

Sharpe shook his head. ‘I don’t know, Sergeant. I’ve a feeling they’re not far away.’ He turned and looked across the river, at the road they had marched the day before. ‘Still no sight of the Spanish.’

Harper was drying himself with his shirt. ‘Perhaps they’ll not turn up, sir.’

It had occurred to Sharpe that possibly the whole job would be done before the Regimienta reached Valdelacasa and he wondered why he still felt the stirrings of concern about the mission. Simmerson had behaved with restraint, the artificers were hard at work, and there were no French in sight. What could go wrong? He walked to the entrance of the bridge and nodded to Lennox. ‘Anything?’

The Scotsman shook his head. ‘All’s quiet. I reckon Sir Henry won’t get his battle today.’

‘He wanted one?’

Lennox laughed. ‘Keen as mustard. I suspect he thinks Napoleon himself is coming.’

Sharpe turned and stared down the road. Nothing moved. ‘They’re not far away. I can feel it.’

Lennox looked at him seriously. ‘You think so? I thought it was us Scots who had the second sight.’ He turned and looked with Sharpe at the empty horizon. ‘Maybe you’re right, Sharpe. But they’re too late.’

Sharpe agreed and walked on to the bridge. He chatted with Knowles and Denny and, as he left them to join Hogan, he reflected gloomily on the atmosphere in the officers’ mess of the South Essex. Most of the officers were supporters of Simmerson, men who had first earned their commissions with the Militia, and there was bad feeling between them and the men from the regular army. Sharpe liked Lennox, enjoyed his company, but most of the other officers thought the Scotsman was too easy with his company, too much like the Riflemen. Leroy was a decent man, a loyalist American, but he kept his thoughts to himself as did the few others who had little trust in their Colonel’s ability. He pitied the younger officers, learning their trade in such a school, and was glad that as soon as this bridge was destroyed his Riflemen would get away from the South Essex into more congenial company.