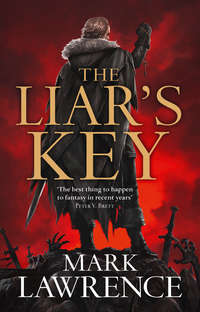

The Liar’s Key

‘She is not welcome here,’ Kara said, and returned to steering the boat.

‘She and Baraqel are all Snorri and I have in our corner. They’re ancient spirits, angel and … well… There are people after us, things, after us that work magic as easily as breathing. We need them. The Red Queen’s sister gave us—’

‘The Red Queen moves you on her board like all her other pawns. What she gives you is as much a collar as a weapon.’ Kara took up the tiller again. Adjusted course. ‘Don’t be fooled about these creatures’ nature. Baraqel is no more a valkyrie or angel than you or me. He and Aslaug were human once. Some among the Builders copied themselves into their machines – others, when the Wheel first turned, escaped their flesh into new forms.’

‘Aslaug never told me—’

‘She’s the daughter of lies, Jalan!’ Kara shrugged. ‘Besides, she probably doesn’t remember. Their spirits have been shaped by expectation for so long. When the Day of a Thousand Suns came their will released them and they were free. Gods in an empty world … then we came back. New men, roaming the earth as the poisons faded. New will. And slowly, without us knowing it, or them, our stories bound about the spirits and our will made them into something suited to our expectations.’

‘Uh.’ I leaned back, trying to make sense of the völva’s words. After a while my head started to hurt. So I stopped, and watched the waves instead.

We sailed on. Snorri and Kara seemed to find excitement in each newly revealed stretch of dreary Norse coastline. Even the sea itself could fascinate them. The swell is doing that, the wind is turning, the rocks are this, the current is westerly. Pah. I’d heard more interesting discussions between herdmen cataloguing the ailments of sheep. Or I probably would have if I’d listened.

A consequence of boredom is that a man is forced to look either to the future or the past, or sideways into his imagination. I tend to find my imagination too worrisome to contemplate, and I had already exhausted the possible scenarios for my homecoming. So, sulking in the Errensa’s prow I spent long hours considering the circumstances of my abduction from Red March and forced march across half of Empire to the Black Fort. Time and again my thoughts returned to great uncle Garyus and his silent sister – born a conjoined monstrosity, the rightful king and queen of Red March. Their father, Gholloth had set the chirurgeons to splitting them, but neither could ever be set upon the throne when age claimed him. He passed them over for Alica, the younger sister. My grandmother. A less obvious monster. But which of them ruled? Which of them had truly set Snorri and myself upon our path north? Which of them had gambled my life and soul against the Dead King? The blood-men with their sharp knives and blunt opinions had cut Garyus from his sister, but the twins had not split even. Garyus a broken teller of stories, his nameless sister a silent voyeur of years yet to come. And Grandmother, the Red Queen, the beating heart of the Marches for a generation, the iron queen with no give in her, her armies feared across the south, her name reviled.

In the empty hours memories plagued me as they are wont to do with nothing to drown out their whispering. Garyus had given me Mother’s locket, and over years I’d so wrapped it in lies that I couldn’t see its value when sat in my palm. Perhaps I’d been equally blind to its purpose. Dr Taproot, the man who had known obscure facts about the Scraa slopes and Nfflr ridges of the Uuliskind, had told me a thing about my mother and I had laughed at his mistake. Had I wrapped her life in as many lies as her locket? Did I look at her death with the same blindness that had hidden the locket’s nature from me?

It’s not like me to brood on the past. I’m not comfortable with uncomfortable truths. I prefer to round off the edges and corners until I have something worth keeping. But a boat and the wide sea give a man little else to do.

‘Show me the key,’ I said.

Snorri sat beside me trailing a line and hook into the sea. He’d caught nothing in all the hours he’d been at it.

‘It’s safe.’ He placed a hand on his chest.

‘I don’t think that thing can be described as safe.’ I sat up to face him. ‘Show it to me.’

With reluctance Snorri tied his line to the oarlock and drew the key from his shirt. It didn’t look like part of the world. It looked as if it had no place there in the daylight. As the key turned on its thong it seemed to change, flickering from one possibility to the next. I supposed a key that could open any lock had to entertain many shapes. I reached for it, but Snorri pushed my hand aside.

‘Best not.’

‘You’re worried I’ll drop it in the sea?’ I asked.

‘You might.’

‘I won’t.’ Hand held out.

Snorri raised a brow. A simple but eloquent expression. I had been known to lie before.

‘We came as close to dying for this thing as men can come, Snorri. Both of us. I have a right.’

‘It wasn’t for the key.’ Voice low, eyes seeing past me now. ‘We didn’t go for the key.’

‘But it’s all we got,’ I said, angry that he should deny me.

‘It’s not a thing you want to touch, Jal. There’s no joy in it. As a friend I say don’t do this.’

‘As a prince of Red March I say give me the fucking key.’

Snorri lifted the thong from about his neck and with a sigh dangled the key into my palm, still retaining the tie.

I closed my hand about it. For the briefest moment I considered ripping it free and arcing it out across the water. In the end I lacked either the courage or the cruelty to do it. I’m not sure which.

‘Thank you.’ The thing seemed to shift in my grasp and I squeezed it to force one form upon it.

There isn’t much I remember about my mother. Her hair – long, dark, smelling of softness. I recall how safe her arms felt. I remember the comfort in her praise, though I could summon none of the words to mind. The sickness that took her I recollected as the story I told about it when people asked. A story without drama or tragedy, just the everyday futility of existence. A beautiful princess laid low by common disease, wasted away without romance by a flux. Isolated by her contagion – her last words spoken to me through a screen. The betrayal a child feels when a parent abandons them returned to me now – still sharp.

‘Oh.’ And without transition the key was no longer a key. I held my mother’s hand, or she held mine, a seven-year-old boy’s hand encompassed in hers. I caught her scent, something fragrant as honeysuckle.

Snorri nodded, his eyes sympathetic. ‘Oh.’

Without warning the boat, the sea, Snorri, all of it vanished, just for the beat of a heart. A blinding light took its place, dazzling, dying away as I blinked to reveal a familiar chamber with star-shaped roundels studding the ceiling. A drawing room in the Roma Hall where my brothers and I would play on winter nights. Mother stood there, half bent toward me, a smile on her face – the face in my locket, but smiling, eyes bright. All replaced a moment later with the boat, the sky, the waves. ‘What?’ I dropped the key as though it had bitten me. It swung from Snorri’s hand on the thong. ‘What!’

‘I’m sorry.’ Snorri tucked the key away. ‘I warned you.’

‘No.’ I shook my head. Too young she was for the assassin’s blade. Taproot’s words, as if he spoke them in my ear. ‘No.’ I stood up, staggered by the swell. I closed my eyes and saw it again. Mother bending toward me, smiling. The man’s face looming over her shoulder. No smile there. Half familiar but not a friend. Features shadowed, offered only in rumour, hair so black as to be almost the blue beneath a magpie’s wing, with grey spreading up from the temples.

The world returned. Two steps brought me to the mast and I clung for support, the sail flapping inches from my nose.

‘Jal!’ Snorri called, motioning for me to come back and sit before the sweep of the boom took me into the water.

‘There was a blade, Snorri.’ Each blink revealed it, light splintering from the edge of a sword held low and casual, the fist at his side clenched about its hilt. ‘He had a sword!’ I saw it again, some secret hidden in the dazzle of its steel, putting an ache in my chest and a pain behind my eyes.

‘I want the truth.’ I stared at Kara. Aslaug hadn’t arrived with the setting sun. To me, that was proof enough of the völva’s power. ‘You can help me,’ I told her.

Kara sighed and bound the tiller. The wind had fallen to a breeze. The sails would soon be furled. She sat beside me on the bench and looked up to study my face. ‘Truth is rarely what people want, Prince Jalan.’

‘I need to know.’

‘Knowledge and truth are different things,’ Kara said. She brushed stray hair from her mouth. ‘I want to know, myself. I want to know many things. I braved the voyage to Beerentoppen, sought out Skilfar, all in search of knowing. But knowledge is a dangerous thing. You touched the key – against Snorri’s strongest advice – and it brought you no peace. Now I advise you to wait. We’re aimed at your homeland. Ask your questions there, the traditional way. The answers are likely not secrets, just facts you’ve avoided or misplaced whilst growing up.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги