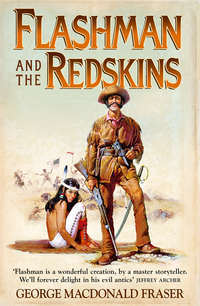

Flashman and the Redskins

It was the most ordinary, trivial thing, and it changed the course of my life, as such things do. Perhaps it killed Custer; I don’t know. As I took my first step from the table a tall man standing at the bar roared with laughter, and stepped back, just catching me with his shoulder. Another instant and I’d have been past him, unseen – but he jostled me, and turned to apologise.

‘Your pardon, suh,’ says he, and then his eyes met mine, and stared, and for full three seconds we stood frozen in mutual recognition. For I knew that face: the coarse whiskers, the scarred cheek, the prominent nose and chin, and the close-set eyes. I knew it before I remembered his name: Peter Omohundro.

You all know these embarrassing little encounters, of course – the man you’ve borrowed money off, or the chap whose wife has flirted with you, or the people whose invitation you’ve forgotten, or the vulgarian who accosts you in public. Omohundro wasn’t quite like these, exactly – the last time we’d met I’d been stealing one of his slaves, and shots had been flying, and he’d been roaring after me with murder in his eye, while I’d been striking out for the Mississippi shore. But the principle was the same, and so, I flatter myself, was my immediate behaviour.

I closed my mouth, murmured an apology, nodded offhand, and made to pass on. I’ve known it work, but not with this indelicate bastard. He let out an appalling oath and seized my collar with both hands.

‘Prescott!’ he bawled. ‘By God – Prescott!’

‘I beg your pardon, sir,’ says I, damned stiff. ‘I haven’t the honour of your acquaintance.’

‘Haven’t you, though, you nigger-stealin’ son-of-a-bitch! I sure as hell got the honour o’ yores! Jim – git a constable – quick, dammit! Why, you thievin’ varmint!’ And while they gaped in astonishment, he thrust me by main strength against the wall, pinning me there and roaring to his friends.

‘It’s Prescott – Underground Railroader that stole away George Randolph on the Sultana last year! Hold still, goddam you! It’s him, I say! Here, Will, ketch hold t’other arm – now, you dog, you, hold still there!’

‘You’re wrong!’ I cried. ‘I’m someone else – you’ve got the wrong man, I say! My name’s not Prescott! Get your confounded hands off me!’

‘He’s English!’ bawled Omohundro. ‘You all hear that? The bastard’s English, an’ so was Prescott! Well, you dam’ slave-stealer, I got you fast, and you’re goin’ to jail till I can get you ’dentified, and then by golly they gonna hang you!’

As luck had it, there weren’t above a dozen men in the place, and while those who’d been with Omohundro crowded round, the others stared but kept their distance. They were a fairly genteel bunch, and Omohundro and I were both big strapping fellows, which can’t have encouraged them to interfere. The man addressed as Jim was hanging irresolute half way to the door, and Will, a burly buffer in a beard and stove-pipe hat, while he laid a hand on my arm, wasn’t too sure.

‘Hold on a shake, Pete,’ says he. ‘You certain this is the feller?’

‘Course I’m sartin, you dummy! Jim, will you git the goddam constable? He’s Prescott, I tell you, an’ he stole the nigger Randolph – got him clear to Canada, too!’

At this two of the others were convinced, and came to lend a hand, seizing my wrists while Omohundro took a breather and stepped back, glowering at me. ‘I’d know the sneakin’ blackguard anywhere – an’ his dadblasted fancy accent—’

‘It’s a lie!’ I protested. ‘A fearful mistake, gentlemen, I assure you … the fellow’s drunk … I never saw him in my life – or his beastly nigger! Let me loose, I say!’

‘Drunk, am I?’ shouts Omohundro, shaking his fist. ‘Why, you brass-bollocked impident hawg, you!’

‘Tarnation, shet up, can’t ye?’ cries Will, plainly bewildered. ‘Why, he sure don’t talk like a slave-stealer, an’ that’s a fact – but, see here, mister, jes’ you rest easy, we git this business looked to. And you hold off, Pete; Jim can git the constable while we study this thing. You, suh!’ This was to Spring, who hadn’t moved a muscle, and was standing four-square, his hands jammed in his pockets, watching like a lynx. ‘You was settin’ with this feller – can you vouch for him, suh?’

They all looked to Spring, who glanced at me bleakly and then away. ‘I never set eyes on him before,’ says he deliberately. ‘He came to my table uninvited and begged for drink.’ And on that he turned towards the door, the perfidious wretch, while I was stricken speechless, not only at the brute’s brazen treachery, but at his folly. For:

‘But you was talkin’ with him a good ten minutes,’ says Will, frowning. ‘Talkin’ an’ laughin’ – why, I seen you my own self.’

‘They come in together,’ says another voice. ‘Arm in arm, too,’ and at this Omohundro moved nimbly into Spring’s path.

‘Now, jes’ you hold on there, mister!’ cries he suspiciously. ‘You English, too, ain’t you? An’ you settin’ all cosy-like with this ’bolitionist skunk Prescott – ’cos I swear on a ton o’ Bibles, Will, that Prescott agin’ the wall there. I reckon we keep a grip o’ both o’ you, till the constable come.’

‘Stand out of my way,’ growls Spring, and although he didn’t raise his voice, it rasped like a file. Will gave back a step.

‘You min’ your mouth!’ says Omohundro, and braced himself. ‘Mebbe you clear, maybe you ain’t, but I warnin’ you – don’t stir another step. You gonna stay here – so now!’

I wouldn’t feel sorry for Omohundro at any time, least of all with two of his bullies pinioning me and blowing baccy juice in my face, but I confess to a momentary pang just then, as though he’d passed port to the right. For giving orders to J. C. Spring is simply one of the things that are never done; you’d be better teasing a mating gorilla. For a moment he stood motionless, while the scar on his brow turned purple, and that unholy mad spark came into his eyes. His hands came slowly from his pockets, clenched.

‘You infernal Yankee pipsqueak!’ says he. ‘Stand aside or, by heaven, it will be the worse for you!’

‘Yankee?’ roars Omohundro. ‘Why, you goddam—’ But before his fist was half-raised, Spring was on him. I’d seen it before, of course, when he’d almost battered a great hulking seaman to death aboard ship; I’d been in the way of his fist myself, and it had been like being hit with a hammer. You’d barely credit it; here was this sober-looking, middle-aged bargee, with the grey streaks in his trim beard and the solid spread to his middle, burly but by no means tall, as proper a citizen as ever spouted Catullus or graced a corporation – and suddenly it was Attila gone berserk. One short step he took, and sank his fists left and right in Omohundro’s midriff; the planter squawked like a burst football, and went flying over a table, but before he had even reached the ground, Spring had seized the dumbfounded Will by the collar and hurled him with sickening force against the wall.

‘And be damned to all of you!’ roars he, jerking down his hat-brim, which was unwise, for it gave the fellow Jim time to wallop him with a chair. Spring turned bellowing, but before Jim could reap the consequences of his folly, one of the coves holding me had let loose, and collared Spring from behind. If I’d been wise I’d have stayed still, but with only one captor I tried to struggle free, and he and I went down wrestling together; he wasn’t my weight, and after some noisy panting and clawing I got atop of him and pounded him till he hollered. Given time, I’d have enjoyed myself for a minute or two pulping his figurehead, but flight was top of the menu just then, so I rolled off him and came up looking frantically for the best way to bolt.

Hell’s delight was taking place a yard away; Omohundro was on his feet again, clutching his belly – which must have been made of cast-iron – and retching for breath; the fellow Will was on the floor but had a hold on Spring’s ankle, which I thought uncommon game of him, while my other captor had Spring round the neck. Even as I looked, Spring sent him flying and turned to stamp on Will’s face – those evenings in the Oriel combination room weren’t wasted, thinks I – and then a willowy cove among the onlookers took a hand, shrieking in French and trying to brain my gallant captain with an ebony cane.

Spring grabbed it and jerked – and the cane came away in his hand, leaving the Frog holding two feet of naked, glittering steel, which he flourished feebly, with Gallic squeals. Poor fool, there was a sudden flurry, the snap of a breaking bone, the Frog was screaming on the floor, and Spring had the sword-stick in his hand. I heard Omohundro’s shout as he flung himself at Spring, hauling a pistol from beneath his coat; Spring leaped to meet him, bawling ‘Habet!’ – and, by God, he had. Before my horrified gaze Omohundro was swaying on tiptoe, staring down at that awful steel that transfixed him; he flopped to his knees, the pistol clattering to the floor, and fell forward on his face with a dreadful groan.

There was a dead silence, broken only by the scraping of Omohundro’s nails at the boards – and presently by a wild scramble of feet as one of the principal parties withdrew from the scene. If there’s one thing I know, it’s when to leave; I was over the counter and through the door behind it like a shot, into a store-room with an open window, and then tearing pell-mell up an alley, blind to all but the need to escape.

How far I ran, I don’t know, doubling through alleys, over fences, across backyards, stopping only when I was utterly blown and there was no sound of pursuit behind. By the grace of God it was coming on to evening, and the light was fading fast; I staggered into an empty lane and panted my soul out, and then I took stock.

That was escape to England dished, anyway; Spring’s passage out was going to be at the end of a rope, and unless I shifted I’d be dancing alongside him. Once the traps had me the whole business of the slavers Cassy had killed would be laid at my door – hadn’t I seen the reward bill naming me murderer? – and the Randolph affair and Omohundro would be a mere side-dish. I had to fly – but where? There wasn’t a safe hole for me in the whole damned U.S.A.; I forced down my panic, and tried to think. I couldn’t run, I had to hide, but there was nowhere – wait, though, there might be. Susie Willinck had sheltered me before, when she’d thought I was an American Navy deserter – but would she do it now, when they were after me for the capital act? But I hadn’t killed Omohundro – she needn’t even know about him, or Spring. And she’s been besotted with me, the fond old strumpet, piping her eye when I left her – aye, a little touch of Harry in the night and she’d be ready to hide me till the next election.

But the fix was, I’d no notion of where in New Orleans I might be, or where Susie’s place lay, except that it was in the Vieux Carré. I daren’t strike off at random, with the Navy’s bulldogs – and the civil police, too, by now – on the lookout for me. So I set off cautiously, keeping to the alleys, until I came on an old nigger sitting on a doorstep, and he put me on the right road.

The Vieux Carré, you must know, is the old French heart of New Orleans, and one gigantic fleshpot – fine houses and walks, excellent eating-places and gardens, brilliantly lit by night, with music and gaiety and colour everywhere, and every second establishment a knocking-shop. Susie’s bawdy-house was among the finest in New Orleans, standing in its own tree-shaded grounds, which suited me, for I intended to sneak in through the shrubbery and seek out my protectress with the least possible ado. Keeping away from the main streets, I found my way to that very side-alley where months earlier the Underground Railroad boys had got the drop on me; it was empty now, and the side-gate was open, so I slipped in and went to ground in the bushes where I could watch the front of the house. It was then I realised that something was far amiss.

It was one of these massive French colonial mansions, all fancy ironwork and balustrades and slatted screens, just as I remembered it, but what was missing now was signs of life – real life, at any rate. The great front door and windows should have been wide to the warm night, with nigger music and laughter pouring out, and the chandeliers a-glitter, and the half-naked yellow tarts strutting in the big hall, or taking their ease on the verandah like tawny cats on the chaise-longues, their eyes glowing like fireflies out of the shadows. There should have been dancing and merriment and drunken dandies taking their pick of the languid beauties, with the upper storeys shaking to the exertions of happy fornicators. Instead – silence. The great door was fast, and while there were lights at several of the shuttered windows, it was plain that if this was still a brothel, it must be run by the Band of Hope.

A chill came over me that was not of the night air. All of a sudden the dark garden was eerie and full of dread. Faint music came from another house beyond the trees; a carriage clopped past the distant gates; overhead a nightbird moaned dolefully; I could hear my own knees creaking as I crouched there, scratching the newly healed bullet-wound in my backside and wondering what the deuce was wrong. Could Susie have gone away? Terror came over me like a cold drench, for I had no other hope.

‘Oh, Christ!’ I whispered half-aloud. ‘She must be here!’

‘Who must be?’ grated a voice at my ear, a hand like a vice clamped on my neck, and with a yap of utter horror I found myself staring into the livid, bearded face of John Charity Spring.

‘Shut your trap or I’ll shut it forever!’ he hissed. ‘Now then – what house is that, and why were you creeping to it? Quick – and keep your voice down!’

He needn’t have fretted; the shock of that awful moment had almost carried me off, and for a spell I couldn’t find my voice at all. He shook me, growling, while I absorbed the dreadful realisation that he must have been dogging me all the way – first in my headlong flight, then on the streets, unseen. It was horrifying, the thought of that maniac prowling and watching my every move, but not as horrifying as his presence now, those pale eyes glaring round as he scanned the house and garden. And knowing him, I answered to the point, in a hoarse croak.

‘It … it belongs to a friend … of mine. A … an Englishwoman. But I don’t know … if she’s there now.’

‘Then we’ll find out,’ says he. ‘Is she safe?’

‘I … I don’t know. She … she took me in once before …’

‘What is she – a whore?’

‘No … yes … she owns the place – or did.’

‘A bawd, eh?’ says he, and bared his teeth. ‘Trust you to make for a brothel. Plura faciunt homines e consuetudine, quam e ratione,fn1 you dirty little rip. Now then, see here. Thanks to you, I’m in a plight; can I lie up in that ken for a spell? And I’m asking your opinion, not your bloody permission.’

My answer was true enough. ‘I don’t know. Christ, you killed a man back there – she may … may not …’

‘Self-defence!’ snarls he. ‘But we agree, a New Orleans jury may take a less enlightened view. Now then – this strumpet … she’s English, you say. Good-natured? Tolerant? A woman of sense?’

‘Why … why, yes … she’s a decent sort …’ I sought for words to describe Susie. ‘She’s a Cockney … a common woman, but—’

‘She must be, if she took you in,’ says this charmer. ‘And we have no course but to try. Now then,’ and he tightened his grip until I thought my neck would break, ‘see here. If I go under, you go under with me, d’ye see? So this bitch had better harbour us, for if she doesn’t …’ He shook me, growling like a mastiff. ‘So you’d better persuade her. And mind what Seneca says: Qui timide rogat, docet negare.’

‘Eh?’

‘Jesus, did Arnold teach you nothing? Who asks in fear is asking for a refusal. Right – march!’

I remember thinking as I tapped on the front door, with him at my elbow, brushing his hat on his sleeve: how many poor devils have ever had a mad murderer teaching ’em Latin in the environs of a leaping-academy in the middle of the night – and why me, of all men? Then the door opened, and an ancient nigger porter stuck his head out, and I asked for the lady of the house.

‘Miz Willinck, suh? Ah sorry, suh. Miz Willinck goin’ ’way.’

‘She isn’t here?’

‘Oh no, suh – she here – but she goin’ ’way pooty soon. Our ’stablishment, suh, is closed, pummanent. But if you goin’ next doah, to Miz Rivers, she be ’commodatin’ you gennamen—’

Spring elbowed me aside. ‘Go and tell your mistress that two English gentlemen wish to see her at her earliest convenience,’ says he, damned formal. ‘And present our compliments and our apologies for intruding upon her at this untimely hour.’ As the darkie goggled and tottered away, Spring rounded on me. ‘You’re in my company,’ he snaps, ‘so mind your bloody manners.’

I was looking about me, astonished. The spacious hall was shrouded in dust-sheets, packages were stacked everywhere, bound and labelled as for a journey; it looked like a wholesale flitting. Then from the landing I heard a female voice, shrill and puzzled, and the nigger butler came shambling into view, followed by a stately figure that I knew well, clad in a fine embroidered silk dressing-gown.

As always, she was garnished like Pompadour, her hennaed hair piled high above that plump handsome face, jewels glistening in her ears and at her wrists and on that splendid bosom that I remembered so fondly; even in my anxious state, it did me good just to watch ’em bounce as she swayed down the stairs – as usual in the evening, she plainly had a pint or two of port inside her. She descended grand as a duchess, peering towards us in the hall’s dim light, and then she checked with a sudden scream of ‘Beauchamp!’ and came hurrying down the last few steps and across the hall, her face alight.

‘Beauchamp! You’ve come back! Well, I never! Wherever ’ave you been, you rascal! I declare – let’s ’ave a look at you!’

For a moment I was taken aback, until I recalled that she knew me as Beauchamp Millward Comber – God knew how many names I’d passed under in America: Arnold, Prescott, Fitz-something-or-other. But at least she was glad to see me, glowing like Soul’s Awakening and holding out her hands; I believe I’d have been enveloped if she hadn’t checked modestly at the sight of Spring, who was bowing stiffly from the waist with his hat across his guts.

‘Susie,’ says I, ‘this is my … my friend, Captain John Charity Spring.’

‘Ow, indeed,’ says she, and beamed at him, up and down, and blow me if he didn’t take her hand and bow over it. ‘Most honoured to make your acquaintance, marm,’ says he. ‘Your humble obedient.’

‘I never!’ says Susie, and gave him a roving look. ‘A distinguished pleasure, I’m sure. Oh, stuff, Beauchamp – d’you think I’m goin’ to do the polite with you, too? Come ’ere, an’ give us a kiss!’

Which I did, and a hearty slobber she made of it, while Spring looked on, wearing what for him passed as an indulgent smile. ‘An’ wherever ’ave you been, then? – I thought you was back in England months ago, an’ me wishin’ I was there an’ all! Now, come up, both of you, an’ tell me wot brings you back – my, I almost ’ad apoplexy, seeing you sudden like that …’ And then she stopped, uncertain, and the laughter went out of her fine green eyes, as she looked quickly from one to other of us. She might be soft where well-set-up men were concerned, but she was no fool, and had a nose for mischief that a peeler would have envied.

‘Wot’s the matter?’ she said sharply. Then: ‘It’s trouble – am I right?’

‘Susie,’ says I, ‘it’s as bad as can be.’

She said nothing for a moment, and when she did it was to tell the butler, Brutus, to bar the door and admit no one without her leave. Then she led the way up to her private room and asked me, quite composed, what was up.

It was only when I began to tell it that the enormity of what I was saying, and the risk I was running in saying it, came home to me. I confined it to the events of that day, saying nothing of my own adventures since I’d last seen her – all she had known of me then was that I was an Englishman running from the Yankee Navy, a yarn I’d spun on the spur of the moment. As I talked, she sat upright on her chair in the silk-hung salon, her jolly, handsome face serious for once, and Spring was mum beside me on the couch, holding his hat on his knees, prim as a banker, although I could feel the crouched force in him. I prayed Susie would play up, because God knew what the lunatic would do if she decided to shop us. I needn’t have worried; when I’d done, she sat for a moment, fingering the tassels on her gaudy bedgown, and then says:

‘No one knows you’re ’ere? Well, then, we can take our time, an’ not do anythin’ sudden or stupid.’ She took a long thoughtful look at Spring. ‘You’re Spring the slaver, aren’t you?’ Oh, Moses, I thought, that’s torn it, but he said he was, and she nodded.

‘I’ve bought some of your Havana fancies,’ says she. ‘Prime gels, good quality.’ Then she rang for her butler, and ordered up food and wine, and in the silence that followed Spring suddenly spoke up.

‘Madam,’ says he, ‘our fate is in your hands,’ which seemed damned obvious to me, but Susie just nodded again and sat back, toying with her long earring.

‘An’ you say it was self-defence? ’E barred your way, an’ there was a ruckus, an’ ’e drew a pistol on you?’ Spring said that was it exactly, and she pulled a face.

‘Much good that’d do you in court. I daresay ’is pals would tell a different tale … if they’re anythin’ like ’e was. Oh, I’ve ’ad ’im ’ere, this Omo’undro, but not above once, I can tell you. Nasty brute.’ She wrinkled her nose in distaste. ‘What they call a floggin’ cully – not that ’e was alone in that, but ’e was a real vile ’un, know wot I mean? Near killed one o’ my gels, an’ I showed him the door. So I shan’t weep for ’im. An’ if it was ’ow you say it was – an’ I’ll know that inside the hour, though I believe you – then you can stay ’ere till the row dies down, or—’ and she seemed to glance quickly at me, and I’ll swear she went a shade pinker ‘—we can think o’ somethin’ else. There’s only me an’ the gels and the servants, so all’s bowmon. We don’t ’ave no customers these days.’

At that moment Brutus brought in a tray, and Susie went to see rooms prepared for us. When we were alone Spring slapped his fist in triumph and made for the victuals.

‘Safe as the Bank. We could not have fallen better.’

Well, I thought so, too, but I couldn’t see why he was so sure and trusting, and said so; after all, he didn’t know her.

‘Do I not?’ scoffs he. ‘As to trust, she’ll be no better than any other tearsheet – we notice she don’t bilk at abetting manslaughter when it suits her whim. No, Flashman – I see our security in that full lip and gooseberry eye, which tell me she’s a sensualist, a voluptuary, a profligate wanton,’ growls he, tearing a chicken leg in his teeth, ‘a great licentious fleshtrap! That’s why I’ll sleep sound – and you won’t.’

‘How d’you mean?’

‘She can’t betray me without betraying you, blockhead!’ He grinned at me savagely. ‘And we know she won’t do that, don’t we? What – she never took her eyes off you! She’s infatuated, the poor bitch. I supposed you stallioned her out of her wits last time. Aye, well, you’d best fortify yourself, for soevit amor ferri,fn2 or I’m no judge; the lady is working up an appetite this minute, and for our safety’s sake you’d best satisfy it.’

Well, I knew that, but if I hadn’t, our hostess’s behaviour might have given me a hint, just. When she came back, having plainly repainted, she was flushed and breathless, which I guessed was the result of having laced herself into a fancy corset under the gown – that told me what was on her mind, all right; I knew her style. It was in her restless eye, too, and the cheerful way she chattered when she obviously couldn’t wait to be alone with me. Spring presently begged to be excused, and bowed solemnly over her hand again, thanking her for her kindness and loyalty to two distressed fellow-countrymen; when Brutus had led him off, Susie remarked that he was a real gent and a regular caution, but there was something hard and spooky about him that made her all a-tremble.