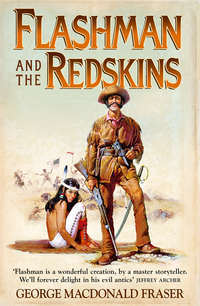

Flashman and the Redskins

‘We can’t do anything,’ says I. ‘What, doctor a lot of sick Indians? We’ve nothing but jallup and sulphur, and it’d be poor business wasting it on a pack of savages. Anyway, God knows what foul infection they’ve got – it might be plague!’

‘’Pears it’s a big gripe in their innards,’ says he. ‘No festerin’ sores, nuthin’ thataway. But thar keelin’ over in windrows, the chief say. En he reckons we got med’cine men in our train who cud—’

‘Who, in God’s name? Not our party of invalids? Christ, they couldn’t cure a chilblain – they can’t even look after themselves! They’ve been wheezing and hawking all the way from Council Grove!’

‘Cheyenne don’t know that – but they see th’ gear en implements on the coaches. See them coons doctorin’ tharselves with them squirt-machines. They want ’em doctor thar people, too.’

‘Well, tell ’em we can’t, dammit! We’ve got to get on; we can’t afford to mess with sick Indians!’

He gave me the full stare of those blue eyes. ‘Cap’n – we cain’t ’fford not to. See, hyar’s the way on’t. Cheyenne ’bout the only real friendlies on these yar Plains – ’thout them, ifn they die or go ’way, we get bad Injun trouble. That the best side on’t. At wust – we give ’em the go-by, they don’t fergit. Could be we even hev ’em ki-yickin’ roun’ our waggons wi’ paint on – en thar’s three thousand on ’em ’cross the river, en Osage an’ ’Rapaho ter boot. That a pow’ful heap o’ Injun, cap’n.’

‘But we can’t help them! We’re not doctors, man!’

‘They kin see us tryin’,’ says he.

There was no arguing with him, and I’d have been a fool to try; he knew Indians and I didn’t. But I was adamant against going down to their camp, which would be reeking with their bloody germs – let them bring one of their sick to the far bank of the river, and if it would placate them for one of our invalids to look at him, or put up a prayer, or spray him with carbolic, or dance in circles round him, so be it. But I told him to impress on them that we were not doctors, and could promise no cure.

‘They best hyar it f’m you,’ says he. ‘You big chief, wagon-captain.’ And he was in dead earnest, too.

So now you see Big Chief Wagon-Captain, standing before a party of assorted nomads, palavering away with a few halting Sioux phrases, but Wootton translating most of the time, while I nodded, stern but compassionate. And I wasn’t acting, either; one look at this collection and I took Wootton’s point. They were the first Cheyenne I’d ever seen close to, and if the Brulé Sioux had been alarming, these would have put the fear of God up Wellington. On average, they were the biggest Indians I ever saw, as big as I am – great massive-shouldered brutes with long braided hair and faces like Roman senators, and even in their distress, proud as grandees. We went with them to the river bank, taking the Major commanding the fort in tow, and the most active and intelligent of our invalids – he was a hobbling idiot, but all for it; let him at the suffering heathen, and if it was asthma or bronchitis (which it plainly wasn’t) he’d have them skipping like goats in no time. Then we waited, and presently a travois was dragged up on the far bank, and Wootton and I and the invalid, with the Cheyenne guiding the way, crossed the ford and mud-flats, and the invalid took a look at the young Indian who was lying twitching on the travois, feebly clutching at his midriff. Then he raised a scared face to me.

‘I don’t know,’ says he. ‘It looks as though he has food poisoning, but I fear … they had an epidemic back East, you know. Perhaps it’s … cholera.’

That was enough for me. I ordered the whole party back to our side of the river and told Wootton that right, reason or none, we weren’t meddling any further.

‘Tell them it’s a sickness we know, but we can’t cure it. Tell them it’s … oh, Christ, tell ’em it’s from the Great Spirit or something! Tell them to get every well person away from their camp – that there’s nothing they can do. Tell ’em to go south, and to boil their water, and … and, I don’t know, Uncle Dick. There’s nothing we can do for them – except get as far away from them as we can.’

He told them, while I racked my brain for a suitable gesture. They heard him in silence, those half-dozen Cheyenne elders, their faces like stone, and then they looked at me, and I did my best to look full of manly sympathy, while I was thinking, Jesus, don’t let it spread to us, for I’d seen it in India, and I knew what it could do. And we had no doctors, and no medicines.

‘I told ’em our hearts are on the ground,’ says Wootton.

‘Good for you,’ says I, and then I faced them and spread my arms wide, palms up, and the only thing I could think of was ‘For what we are about to receive may the Lord make us truly thankful, for Christ’s sake, amen.’ Well, their tribe was dying, so what the hell was there to say?22

It seemed to be the right thing. Their chief, a splendid old file with silver dollars in his braids, and a war-bonnet of feathers trailing to his heels, raised his head to me; he had a chin and nose like the prow of a cruiser, and furrows in his cheeks you could have planted crops in. Two great tears rolled down his cheeks, and then he lifted a hand in salute and turned away in silence, and the others with him. I heaved a great sigh of relief, and Wootton scratched his head and said:

‘They satisfied, I rackon. We done the best thing.’

We hadn’t. Two days later, as we were rolling up to the crossing at Chouteau’s Island, four people in the caravan came down with cholera. Two of them were young men in the Pittsburgh Pirates company; a third was a woman among the emigrant families. The fourth was Wootton.

I’m well aware that, as the poet says, every man’s death diminishes us; I would add only that some diminish us a damned sight more than others, and they’re usually the fellows we took for granted, without ever realising how desperately we depended on them. One moment they’re about, as merry as grigs, and all’s as well as could be, and the next they’ve rolled over and started drumming their heels. And it hits you like a thunderbolt: this ain’t any ordinary misfortune, it’s utter catastrophe. That’s when you learn the true meaning of grief – not for the dear departed, but for yourself.

Wootton didn’t actually depart, thank heaven, but I’ve never seen a human being so close to the edge. He hovered for three days, by which time he was wasted as a corpse, and as I gazed down at him shivering in his buffalo robe after he’d vomited out his innards for the twentieth time, it seemed he might as well have gone over, for all the use he would be to us. The spark was flickering so low that we didn’t dare even move him, and it would plainly be weeks before he could sit a pony, assuming he didn’t pop off in the meantime. And we daren’t wait; already we had barely enough grub to take us to Bent’s, or the big cache on the Cimarron; there wasn’t a sign of another caravan coming up behind, and to crown all, the game had vanished from the prairie, as it does, unaccountably, from time to time. We hadn’t seen a buffalo since Fort Mann.

But grub wasn’t the half of our misfortunes; the stark truth was that without Wootton we were lost souls, and the dread sank into me as I realised it.

Without him, we didn’t have a brain; we were lacking something even more vital than rations or ammunition: knowledge. Twice, for example, we might have had Indian mischief but for him; his presence had been enough to make the Brulés let us alone, and his wisdom had placated the Cheyenne when I might have turned ’em hostile. Without Wootton, we couldn’t even talk properly to Indians, for Grattan’s guards and the teamsters, who’d looked so useful back at Westport, were just gun-toters and mule-skinning louts with no more real understanding of the Plains than I had; Grattan himself had made the trip before, but under orders, not giving ’em, and with seasoned guides showing the way. Half a dozen times, when grazing had been bad, Wootton had known where to find it; without him, our beasts could perish because we wouldn’t know there was good grass just over the next hill. If we hit a two-day dust-storm and lost the trail; if we missed the springs on the south road; if we lost time in torrential rain; if hostiles crossed our path – Wootton could have found the trail again, wouldn’t have missed the springs, would have known where there was a cache, or the likelihood of game, would have sniffed the hostiles two days ahead and either avoided them or known how to manage them. There wasn’t a man in the caravan, now, who could do any of these things.

He had lucid moments, on the third day, though he was still in shocking pain and entirely feeble. He would hole up where he was, he whispered, but we must push on, and if he got better he would make after us. I told him the other sick would stay with him – for one thing, we daren’t risk infection by carrying them with us – and the stricken woman’s husband and brothers would take care of them. We would leave a wagon and beasts and sufficient food. I don’t know if he understood; he had only one thing in his mind, and croaked it out painfully, his skin waxen and his eyes like piss-holes in the snow.

‘Make fer Bent’s … week, ten days mebbe. Don’t … take … Cimarron road … lose trail … You make Bent’s. St Vrain … see you … pretty good. ’Member … not Cimarron. Poor bull23 … thataways …’ He closed his eyes for several minutes, and then looked at me again. ‘You git … train … through. You … wagon-cap’n …’

Then he lost consciousness, and began to babble – none of it more nonsensical than the last three words he’d said while fully conscious. Wagon-captain! And it was no consolation at all to look about me at our pathetic rabble of greenhorns and realise that there wasn’t another man as fit for the job. So I gave the order to yoke up and break out, and within the hour we were creaking on up the trail, and as I looked back at the great desolation behind us, and the tiny figures beside the sick wagon by the river’s edge, I felt such a chill loneliness and helplessness as I’ve seldom felt in my life.

Now you’ll understand that these were not emotions shared by my companions. None of them had seen as much of Wootton as I had, or appreciated how vitally we relied on him; Grattan probably knew how great a loss he was, but to the rest I had always been the wagon-captain, and they trusted me to see them through. That’s one of the disadvantages of being big and bluff and full of swagger – folk tend to believe you’re as good a man as you look. Mind you, I’ve been trading on it all my life, with some success, so I can’t complain, but there’s no denying that it can be an embarrassment sometimes, when you’re expected to live up to your appearance.

So there was nothing for it now but to play the commander to the hilt, and it was all the easier because most of them were in a great sweat to get on – the farther they could leave the cholera behind them, the better they’d like it. And it was simple enough so long as all went well; I had taken a good inventory of our supplies during the three days of waiting to see whether Wootton would live or die, and reckoned that by going to three-quarter rations we should make Bent’s Fort with a little to spare. By the map it couldn’t be much over 120 miles, and we couldn’t go adrift so long as we kept to the river … provided nothing unforeseen happened – such as the grazing disappearing, or a serious change in the weather, or further cases of cholera, or distemper among the animals. Or Indians.

For two days it went smooth as silk – indeed, we made better than the usual dozen to fifteen miles a day, partly because it never rained and the going was easy, partly because I pushed them on for all I was worth. I was never out of the saddle, from one end of the train to the other, badgering them to keep up, seeing to the welfare of the beasts, bullyragging the guards to keep their positions on the flanks – and all the time with my guts churning as I watched the skyline, dreading the sight of mounted figures, or the tiny dust-cloud far across the plain that would herald approaching enemies. Even at night I was on the prowl, in nervous terror as I stalked round the wagons – and keeping mighty close to them, you may be sure – before returning to my tent to rattle my fears away with Cleonie. She earned her com, no error – for there’s nothing like it for distracting the attention from other cares, you know; I even had a romp with Susie, for my comfort more than hers.

Aye, it went too well, for the rest of the train never noticed the difference of Wootton’s absence, and since it had been an easy passage from Council Grove, they never understood what a parlous state we would be in if anything untoward arose now. The only thing they had to grumble at was the shorter commons, and when we came to the Upper Crossing on the third day, the damfools were so drugged with their false sense of security that they made my reduction in rations an excuse for changing course. As though having to make do with an ounce or two less of corn and meat each day mattered a curse against the safety of the entire expedition. Yet that is what happened; on the fourth morning I was confronted by a deputation of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Their spokesman was a brash young card in a cutaway coat with his thumbs hooked in his galluses.

‘See here, captain,’ says he, ‘it’s near a hundred miles to Bent’s Fort – why, that’s another week with empty bellies! Now, we know that if we cross the river on the Cimarron road, there’s the big cache that Mr Wootton spoke of – and it’s less than thirty miles away. Well, me and the boys are for heading for it; it’ll mean only two more days of going short, and then we can replenish with all the grub we want! And everyone knows it’s the short way to Santa Fe – what d’you say, captain?’

‘I say you’re going to Bent’s.’

‘Why so? What’s the point in five days o’ discomfort?’

‘You ain’t in discomfort,’ says I. ‘And your bellies aren’t empty – but they would be if we went the Cimarron road. We’re going to Bent’s as agreed; for one thing, it’s safer.’

‘Who says that, now?’ cries this barrack-room lawyer, and his mates muttered and swore; other folk began to cluster round, and I saw I must scotch this matter on the spot.

‘I say it, and I’ll tell you why. If we were fool enough to leave the river, we could be astray in no time. It’s desert over yonder, and if you lose the trail you’ll die miserably—’

‘Ain’t no reason ter lose the trail,’ cries a voice, and to my fury I saw it was one of Grattan’s guards, a buckskinned brute called Skate. ‘I bin thataways on the cut-off; trail’s as plain as yer hand.’ At which the Pittsburgh oafs hurrahed and clamoured at me.

‘We’re going to Bent’s!’ I barked, and they gave back. ‘Now, mark this – suppose the trail was as good as this fellow says – which I doubt – does anyone know where Wootton’s cache is? No, and you’d never find it; they don’t make ’em with finger-posts, you know. And if you did, you’d discover it contained precious little but jerked meat and beans – well, if that’s your notion of all the grub you want, it ain’t mine. At Bent’s you’ll find every luxury you can imagine, as good as St Louis.’ They still looked surly, so I capped the argument. ‘There’s also more likelihood of encountering hostile tribes along the Cimarron. That’s why Wootton insisted we make for Bent’s – so you can yoke up and prepare to break out.’

‘Not so fast, there!’ says the cutaway coat. ‘We got a word to say to that, if you please—’

I turned my back. ‘Mr Nugent-Hare, you can saddle up,’ I was saying, when Skate pushed forward.

‘This ain’t good enough fer me!’ cries he. ‘You don’t know a dam’ thing more’n we do, mister. Fact, yore jest a tenderfoot, when all’s said—’

‘What’s this, Mr Nugent-Hare?’ cries I. ‘Have you no control of your rascals?’

‘Easy, now, captain,’ says he, pulling his long Irish nose. ‘You’ll mind I said we weren’t in the army.’

‘I say we take a vote!’ bawls Skate, and I noted that most of the guards were at back of him. ‘We all got a say hyar, jest as much as any high-an’-mighty lime-juice sailor – oh, beg pardon, Captain Comber!’ And the scoundrel leered and swept off his cap in an elaborate bow; the Pittsburgh clowns held on to each other, guffawing. ‘En I kin tell yuh,’ continued Skate, ‘thet Dick Wootton wuz jest as consarned ’bout Ute war-parties up on the Picketwire, as ’bout any other Injuns by Cimarron. Well, Picketwire’s nigh on Bent’s, ain’t it? So I’m fer the cut-off, en I say let’s see a show o’ hands!’

Of course the Pirates yelled acclaim, sticking both hands up, and Skate glared round at his mates until most of them followed suit. Grattan turned aside, whistling softly between his teeth; the fathers of the emigrant families were looking troubled, and our invalids were looking scared. I know I was red in the face with rage, but I was holding it in while I considered quickly what to do – I was long past the age when I thought I could bluster my way out of a position like this. In the background I saw Susie looking towards me; behind her the sluts were already seated in the wagons. I shook my head imperceptibly at Susie; the last thing I wanted was her railing at the mutineers.

The Pittsburgh Pirates made up about half our population, so a bare majority was voting for Cimarron. This wasn’t enough for Skate.

‘Come on, you farmers!’ roars he. ‘You gonna let milord hyar tell you whut you kin en cain’t do? Let’s see yer hands up!’

A number of them complied, and the cutaway coat darted about, counting, and turned beaming on me. ‘I reckon we got a democratic majority, captain! Hooraw, boys! Ho for Cimarron!’ And they all cheered like anything, and as it died down they looked at me.

‘By all means,’ says I, very cool. ‘Good day to you.’ And I turned away to tighten the girths on my pony. They stared in silence. Then:

‘What you mean?’ cries Skate. ‘We got a majority! Caravan goes to Cimarron, then!’

‘It’s going to Bent’s,’ says I, quietly. ‘At least, the part of it that I command does. Any deserters—’ I tugged at a strap ‘—can go to Cimarron, or to hell, as they please.’

I was counting on my composure to swing them round, you see; they were used to me as wagon-captain, and I reckoned if I played cool and business-like it would sway them. And indeed, a great babble broke out at once; Skate looked as though he was ready to do murder, but even some of the Pirates looked doubtful and fell to wrangling among themselves. And I believe all would have been well if Susie, who was fairly bursting with fury, hadn’t cut loose at them, abusing Skate in Aldgate language, and even turning on the sober emigrants, insisting that they obey me.

‘You’re bound on oath!’ she shrilled. ‘Why, I’ll have the law on you – you treacherous scallawags, you! You’ll do as you’re bidden, so there!’

I could have kicked her fat satin backside; it was the worst line she could have taken. The leader of the emigrant families, who’d been muttering about how the wagon-captain was the boss, wasn’t he, went dark crimson at Susie’s railing, and drew himself up. He was a fine, respectable-looking elder and his beard fairly bristled at her.

‘Ain’t no hoor-mistress gonna order me aroun’!’ says he, and stalked off; most of the emigrants reluctantly followed him, and the Pittsburgh boys hoorawed anew, and began to make for their wagons. So you see the wagon-captain with his bluff called – and not a thing to be done about it.

One thing I knew, I was not crossing the river. I could see Wootton’s face now. ‘Not Cimarron … poor bull.’ The thought of that desert, and losing the trail, was enough for me. It was all very well for Skate and his pals; if they got lost, they could in desperation ride back to the Arkansas for water, and struggle down to Fort Mann – but the folk in the wagons would be done for. And our own little party was in an appalling fix; we had our eight wagons and the carriage, with their drivers, but we faced a week’s trip to Bent’s without guards. If we met marauding Indians … we would have my guns and those of the teamsters and savaneros.

But I was wrong – we also had the invalids. They approached me with some hesitation and said they would prefer to continue to Bent’s; the air on the north bank of the river was purer, they were sure of that – and they didn’t approve of Skate and those Pittsburgh rapscallions, no, indeed. ‘We, sir, have some notions of loyalty and good behaviour, I hope,’ says the one whose diagnosis of the Cheyenne had proved so accurate. His pals cried bravo and hear, hear! and flourished their sprays and steam-kettles in approval; dear God, thinks I, whores and invalids; at least they were both well-disciplined.

‘I’d better see to the rations, or friend Skate’ll be leaving us the scrapings of the barrel,’ says Nugent-Hare.

‘You’re not going with them?’ says I, astonished.

‘Why would I do that?’ says he. ‘I hired for the trip to California, and I keep my engagements.’ D’ye know, even then, when I should have been grateful at the thought of another good pair of hands, I didn’t believe a word of it. ‘Besides,’ says he, with a gallant inclination to Susie, who was now standing alarmed and woebegone, ‘Grattan’s never the boy to desert a lady in time of trouble, so he’s not.’ And he sauntered off, humming, while my fond spouse assailed me with lamentations and self-reproaches – for she was sharp enough to see that her folly had tipped the balance. If I’d had less on my mind I’d probably have given vent to my feelings, full tilt; as it was I just told her, pretty short, to get into the coach and make sure Skate’s bullies didn’t try to run off any of our crinoline herd.

There was a pretty debate going on round our supply-wagons; Skate was claiming that he and his mates were entitled to food since they had been part of our caravan; Grattan was taking the line that when they stopped working for us, they stopped eating, and if they tried to pilfer he’d drop the first man in his tracks. He pushed back his coat and hooked a thumb in his belt beside his Colt as he said it; Skate bawled and gnashed a bit, but gave way, and I judged the time right to remind the emigrants that if they wished to change their mind, they’d be welcome. None did, and I believe it was simply that they clung to the larger party, and to the firepower of Skate’s fellows.

They were just starting to struggle over the crossing when our depleted party rolled off up the Arkansas, and I scouted to a ridge to see what lay ahead. As usual, it was just rolling plain as far as you could see, with the muddy line of the Arkansas and its fringe of cottonwoods and willows; nothing moved out on that vastness, not even a bird; I sat with my heart sinking as our little train passed me and pitched and rolled slowly down the slope; Susie’s carriage with its skinner, and the servants perched behind; the four wagons whose oxen had been exchanged for mules, and the other four with the cattle teams, all with their drivers. The covers were up on the trulls’ wagons, and there they were in their bonnets against the early sun, sitting demurely side by side. The Cincinnati Health Improvement Society came last in their two carriages, with their paraphernalia on top; you could hear them comparing symptoms at a quarter of a mile.

We made four days up the river without seeing a living thing, and I couldn’t believe our luck; then it rained, such blinding sheets of water as you’ve never seen, sending cataracts across the trail and turning it into a hideous, glue-like mud from which one wagon had to be dragged free by the teams of four others. We took to what higher ground there was, and pushed on through a day that was as dark as late evening, with great blue forks of lightning flickering round the sky and thunder booming incessantly overhead. It died away at nightfall, and we made camp in a little hollow near the water’s edge and dried out. After the raging of the storm everything fell deathly still; we even talked in undertones, and you could feel a great oppression weighing down on you, as though the air itself was heavy. It was dank and drear, without wind, a silence so absolute that you could almost listen to it.

Grattan and I were having a last smoke by the fire, our spirits in our boots, when he came suddenly to his feet and stood, head cocked, while I whinnied in alarm and demanded to know what the devil he was doing. For answer he upended the cooking pot on to the fire with a great hiss and sputter of sparks and steam, and then he was running from wagon to wagon calling softly; ‘Lights out! Lights out!’ while I gave birth and glared about me. Here he was back, dropping a hand on my shoulder, and stifling my inquiries with: ‘Quiet! Listen!’