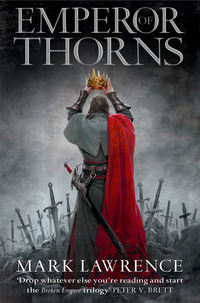

Emperor of Thorns

‘So enjoy the show!’ He shook his head, tried to hide a grimace, then looked at me. ‘What can I do for you, my king?’

‘As always,’ I said. ‘Advice.’

‘You hardly need it. I’ve never even seen Vyene, not even been close. I haven’t got anything that will help you in the Holy City. Sharp wits and all that book learning should serve you well enough. You survived the last Congression, didn’t you?’

I let that memory tug a bleak smile from me. ‘I’ve got some measure of cleverness perhaps, old man, but what I need from you is wisdom. I know you’ve had my library brought through this chamber one book at a time. The men bring you tales and rumour from all corners. Where do my interests lie in Vyene? Where shall I drop my seven votes?’

I stepped closer, across the bare stones. Coddin was ever the soldier: no rugs or rushes for him even as an invalid.

‘You don’t want to hear my wisdom, Jorg. If that’s what it is.’ Coddin turned to the window again, the sun catching his age, and catching the lines that pain had etched into him.

‘I had hoped you’d changed your mind,’ I said. There are hard paths and there are the hardest paths.

The stench of his wound came stronger now I stood close. Corruption is nibbling at our heels from the hour we’re born. The stink of rot just reminds us where our feet are leading us, whichever direction they point in.

‘Vote with your father. Be at peace with him.’

Good medicines often taste foul, but some pills are too bitter to swallow. I paused to take the anger from my voice. ‘It’s been nearly more than I can do not to march my armies into Ancrath and lay waste. If it’s a struggle to keep from open war … how can there be peace?’

‘You two are alike. Your father perhaps a touch colder, more stern and with less ambition, but you fell from the same tree and similar evils forged you.’

Only Coddin could tell me I was my father’s son and live. Only a man who had already died in my employ and lay rotting in my service still, out of duty, only such a man could speak that truth.

‘I don’t need him,’ I said.

‘Didn’t this ghost of yours, this Builder, tell you two Ancraths together would end the power of the hidden hands? Think, Jorg! Sageous set your uncle against you. Sageous wanted you and your brother in the ground. And failing that he drove a wedge between father and son. And what would end the power of men like Sageous, of the Silent Sister, Skilfar, and all their ilk? Peace! An emperor on the throne. A single voice of command. Two Ancraths! You think your father has been idle all this time, the years that grew you, and the years before? He may not have your arching ambition, but he is not without his own measure. King Olidan has influence in many courts. I won’t say he has friends, but he commands loyalty, respect, and fear in equal measures. Olidan knows secrets.’

‘I know secrets.’ Many I did not wish to know.

‘The Hundred will not follow the son whilst the father stands before them.’

‘Then I should destroy him.’

‘Your father took that path – it made you stronger.’

‘He faltered at the last.’ I looked at my hand, remembering how I had lifted it from my chest, dripping crimson. My blood, father’s knife. ‘He faltered. I will not.’

If it had been the dream-witch who drove a wedge between us then he had done his job well. It wasn’t in me to forgive my father. I doubted it was in him to accept such forgiveness.

‘The hidden hands might think two Ancraths will end their power. Me, I think one is enough. It was enough for Corion. Enough for Sageous. I will be enough for all of them if they seek to stop me. In any event, you know in what high esteem I hold prophecy.’

Coddin sighed. ‘Harran is waiting for you. You have my advice. Carry it with you. It won’t slow you down.’

The captains of my armies, nobles from the Highlands, a dozen lords on petitioning visits from various corners of the seven kingdoms, and scores of hangers-on all waited for me in the entrance hall before the keep doors. The time when I could just slip away had … just slipped away. I acknowledged the throng with a raised hand.

‘My lords, warriors of my house, I’m off to Congression. Be assured I will carry your interests there along with my own and present them with my usual blend of tact and diplomacy.’

That raised a chuckle. I’d bled a lot of men dry to take my little corner of empire so I felt I should play out the game for my court, as long as it cost me nothing. And besides, their interests lay with mine, so I hardly lied.

I singled Captain Marten out amongst the crowd, tall and weathered, nothing of the farmer left in him. I gave no rank higher than captain but the man had led five thousand soldiers and more in my name.

‘Keep her safe, Marten. Keep them both safe.’ I put a hand to his shoulder. Nothing else needed to be said.

I came into the courtyard flanked by two knights of my table, Sir Kent and Sir Riccard. The spring breeze couldn’t carry the aroma of horse sweat away fast enough, and the herd of more than three hundred appeared to be doing their best to leave the place knee-deep in manure. I find that massed cavalry are always best viewed from a certain distance.

Makin eased his horse through the ranks to reach us. ‘Many happy returns, King Jorg!’

‘We’ll see,’ I said. It all felt a little too comfortable. Happy families with my tiny queen above. Birthday greetings and a golden escort down below. Too much soft living and peace can choke a man sure as any rope.

Makin raised an eyebrow but said nothing, his smile still in place.

‘Your advisors are ready to ride, sire.’ Kent had taken to calling me sire and seemed happier that way.

‘You should be taking wise heads not men-at-arms,’ Makin said.

‘And who might you be bringing, Lord Makin?’ I had decided to let him select the single advisor his vote entitled him to bring to Congression.

He pointed across the yard to a scrawny old man, pinch-faced, a red cloak lifting around him as the wind swirled. ‘Osser Gant. Chamberlain to the late Baron of Kennick. When I’m asked what my vote will cost, Osser’s the man who will know what is and what isn’t of worth to Kennick.’

I had to smile at that. He might pretend it wasn’t so, but part of old Makin wanted to play out his new role as one of the Hundred in grand style. Whether he would model his rule on my father’s or that of the Prince of Arrow remained unclear.

‘There’s not much of Kennick that ain’t marsh, and what the Ken Marshes need is timber. Stilts, so your muddy peasants’ houses don’t sink overnight. And you get that from me now. So don’t let your man forget it.’

Makin coughed as if some of that marsh had got into his chest. ‘So who exactly are you taking as advisors?’

It hadn’t been a difficult choice. Coddin’s final trip came when they carried him down from the mountain after the battle for the Haunt. He wouldn’t travel again. I had grey heads aplenty at court, but none whose contents I valued. ‘You’re looking at two of them.’ I nodded to Sirs Kent and Riccard. ‘Rike and Grumlow are waiting outside, Keppen and Gorgoth with them.’

‘Christ, Jorg! You can’t bring Rike! This is the emperor’s court we’re talking about! And Gorgoth? He doesn’t even like you.’

I drew my sword, a smooth glittering motion, and hundreds of golden helms turned to follow its arc. I held the blade high, turning it this way and that to catch the sun. ‘I’ve been to Congression before, Makin. I know what games they play there. This year we’re going to play a new game. Mine. And I’m bringing the right pieces.’

2

Several hundred horsemen throw up a lot of dust. We left the Matteracks in a shroud of our own making, the Gilden Guard stretched out across half a mile of winding mountain path. Their gleam didn’t survive long and we made a grey troop as we came to the plains.

Makin and I rode together along the convolutions of the track on which we once met the Prince of Arrow, headed for my gates. Makin looked older now, a little iron in the black, worry lines across his brow. On the road Makin had always seemed happy. Since we came to wealth and fortune and castles he had taken to worry.

‘Will you miss her?’ he asked. For an hour just the clip and clop of hooves on stony ground, and then from nowhere, ‘Will you miss her?’

‘I don’t know.’ I’d grown fond of my little queen. When she wanted to she could excite me, as most women could: my eye is not hard to please. But I didn’t burn for her, didn’t need to have her, to keep her in my sight. More than fondness, I liked her, respected her quick mind and ruthless undercurrents. But I didn’t love her, not the irrational foolish love that can overwhelm a man, wash him away and strand him on unknown shores.

‘You don’t know?’ he asked.

‘We’ll find out, won’t we?’ I said.

Makin shook his head.

‘You’re hardly the champion of true love, Lord Makin,’ I told him. In the six years since we came to the Haunt he had kept no woman with him, and if he had a mistress or even a favourite whore he had them well hidden.

He shrugged. ‘I lost myself on the road, Jorg. Those were black years for me. I’m not fit company for any woman I’d desire.’

‘What? And I am?’ I turned in the saddle to watch him.

‘You were young. A boy. Sin doesn’t stick to a child’s skin the way it clings to a man’s.’

My turn to shrug. He had seemed happier when murdering and robbing than he did thinking back on it in his vaulted halls. Perhaps he just needed something to worry about again, so he could stop worrying.

‘She’s a good woman, Jorg. And she’s going to make you a father soon. Have you thought about that?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘It had slipped my mind.’ In truth though it surfaced in my thoughts in each waking hour, and many dreaming ones. I couldn’t find a way to grip the idea and it did indeed slip from me. I knew a squalling infant would soon appear, but what that would mean to me – what it was to be a father – I had no hold on. Coddin told me I would know how to feel. Instinct would tell me – something written in the blood. And perhaps it would come to me, like a sneeze arriving when pepper’s in the air, but until it did I had no way of imagining it.

‘Perhaps you’ll be a good father,’ Makin said.

‘No.’ Whether I somehow came to understand the process or not I would make a poor father. I had failed my brother and I would doubtless fail my son. Somehow the curse Olidan of Ancrath bestowed on me, and got most likely from his own sire, would infect any child of mine.

Makin pursed his lips but had the grace or the wisdom not to argue.

There’s not much of the Renar Highlands that lies flat enough to grow crops on, but close to the border with Ancrath the land stops leaping and diving long enough for farming and for a city, of sorts. Hodd Town, my capital. I could see the stain of it on the horizon.

‘We’ll camp here,’ I said.

Makin leaned in his saddle to tell Sir Riccard, and he raised my colours on his lance.

‘We could make Hodd Town,’ Makin said. ‘We’d be there an hour or so past sunset.’

‘Bad beds, grinning officials, and fleas.’ I swung out of Brath’s saddle. ‘I’d rather sleep in a tent.’

Gorgoth sat down. He let the guard work around him, tethering their horses, organizing their feed, setting up pavilions, each big enough for six men, with two ribbons streaming from the centre-point, the emperor’s black and gold. Keppen and Grumlow threw their saddlebags beside the leucrota and sat on them to play dice.

‘We should at least pass through town tomorrow, Jorg.’ Makin tied off the feedbag on his mount’s nose and turned back to me. ‘The people love to see the guard ride past. You can give them that at least?’

I shrugged. ‘It should be enough that I keep court in the Highlands. Do you think they’ve forgotten that I’ve a palace bigger than the whole of Hodd Town down in Arrow?’

Makin kept his eyes on mine. ‘Sometimes it seems you’ve forgotten it, Jorg.’

I turned away and squatted to watch the dice roll. The ache in my thighs told me I’d been too long in the throne and the bed and the banquet hall. Makin had it right, I should travel my seven kingdoms, even if it were only to spend time on the road and keep its lessons sharp in my mind.

‘Son of a bitch!’ Keppen spat. All five of Grumlow’s dice showed sixes. Keppen started to empty his coin pouch, spat again, and threw the whole lot down at Grumlow’s feet. I shook my head. It seemed a waste of good fortune to buck such odds for a pouch of coin.

‘Don’t use up all your luck, Brother Grumlow. You might need it later.’ I stood again, biting back a curse at my legs.

I hadn’t wanted to live in the palace Prince Orrin had built for Katherine. I spent a few weeks there after we had secured the allegiance of Arrow’s surviving lords. The building reminded me of Orrin, austere but splendid, high arches, pillars of white stone, it could have been copied from the ruins of Macedon where Alexander grew to greatness. I rattled around in its many rooms with the brothers as my guards, and my captains planning the capture of Arrow’s remaining conquests. The palace felt deserted despite a staff of hundreds, strangers all of them. In the end I’d been glad to ride out to secure Normardy, somehow a relief though it proved the bloodiest of that spring’s campaigns.

If life in the Haunt had left me too soft for a day in the saddle then I was wise to avoid the luxury of that palace. Better the mountains than the plains, better the howl of the wind about snow-clad peaks than the foul air blowing off the Quiet Sea laden with the stench of the Drowned Isles. Besides, in Ancrath and in Renar the blood of my line ran thickest. I might not hunger for the warmth of family but in troubled times it’s wiser to be surrounded by subjects who follow out of habit rather than out of new-found fear.

A gentle rain began to fall as the light faded. I pulled my cloak tighter and moved to one of the campfires.

‘A tent for the king!’ Sir Riccard shouted, catching the arm of a passing guardsman.

‘A little wet won’t hurt me,’ I told him. A good swordsman, Riccard, and brave, but rather too taken with his rank and with shouting.

Time spent around a fire, among the bustle of warriors, was more to my liking than watching the walls of a tent twitch and flap, and imagining what might lie behind them. I watched the guards organize their camp and let the aroma of the stew-pots tease my nose.

When you are a troop of more than three hundred, a small army by most reckonings, all the simple matters of the road require discipline. Latrine trenches must be dug, a watch organized on a defensible perimeter, horses taken to graze and water. Gone the easy ways that suited our band of brothers on the roads of my childhood. Scale changes everything.

A guard captain came with a chair for me, a piece of campaign furniture that would fold down again to a tight flat package with brass-bound corners to weather the knocks and bumps of travel. Captain Harran found me sat in it with a bowl of venison and potatoes in my lap, food from my own stores at the Haunt, no doubt. The guard expected to provision wherever they stopped – a kind of highway robbery legalized by the last echoes of empire.

‘There’s a priest wanting to see you,’ Harran said. I let him drop ‘King Jorg’ into my expectant silence. The captains of the Gilden Guard hold the Hundred in mild contempt and are wont to laugh at our titles behind their oh-so-shiny helms.

‘A priest? Or perhaps the Bishop of Hodd Town?’ I asked. The Gilden Guard have little respect for the church of Roma either, a legacy of centuries punctuated by vicious squabbles between emperors and Popes. For the emperor’s loyalists Vyene is the holy city and Roma an irrelevance.

‘Yes, a bishop.’ Harran nodded.

‘The silly hat gives them away,’ I said. ‘Sir Kent, if you could go and escort Father Gomst to our little circle of piety. I wouldn’t want him coming to grief amongst the guard.’

I sat back in my chair and swigged from a tankard of ale they’d brought me, sour stuff from the breweries of the Ost-Reich. Rike watched the fire, gnawing on a bone from his meal. Most men watch the flames as if seeking answers in the mystery of that bright dance. Rike just scowled. Gorgoth came across and elbowed a space close enough that the glow lit him. Like me he had a measure of understanding when he stared into the flames. The magic I’d borrowed from Gog burned out of me on the day we turned the men of Arrow from the Haunt – it was never truly mine. I think, though, that Gorgoth had wet his hands in what Gog swam through. Not fire-sworn like Gog, but with a touch of it running in his veins.

Grumlow alerted us to Bishop Gomst’s approach, pointing out the mitre swaying above the heads of guardsmen lined for the mess tent. We watched as he emerged, arriving in full regalia with his crook to lean on and a shuffle in his feet, though he had no more years on him than Keppen who could run up a mountain before lunch if the need arose.

‘Father Gomst,’ I said. I’d been calling him that since I could call him anything at all and saw no reason to change my ways just because he’d changed his hat.

‘King Jorg.’ He bowed his head. The rain started to thicken.

‘And what brings the Bishop of Hodd Town out on a damp night like this when he could be warming himself before the votive candles banked in his cathedral?’ A sore point since the cathedral stood half built. I still poked at old Gomsty as if he were stuck in that cage we found him in years back on the lichway. My uncle had over-reached himself when he commissioned the cathedral project, a poorly judged plan conceived the same year my mother squeezed me into the world. Perhaps another bad decision. In any event, the money had run out. Cathedrals don’t come cheap, not even in Hodd Town.

‘I needed to speak with you, my king. Better here than in the city.’ Gomst stood with the rain dripping from the curls of his crook, bedraggled in his finery.

‘Get the man a chair,’ I shouted. ‘You can’t leave a man of God standing in the muck.’ Then in a lower voice, ‘Tell me, Father Gomst.’

Gomst took his time to sit, adjusting his robes, the hems thick with mud. I expected him to come with a priest or two, a church boy to carry his train at least, but my bishop sat before me unattended, dark with rain, and looking older than his years.

‘There was a time when the seas rose, King Jorg.’ He held his crook white-knuckled and stared at the other hand in his lap. Gomst never told stories. He scolded or he flattered, according to the cloth of his audience.

‘The seas rise each day, Father Gomst,’ I said. ‘The moon draws on the deep waters as it draws on women’s blood.’ I knew he spoke of the Flood, but tormenting him came too easy.

‘There were untold years when the seas lay lower, when the Drowned Isles were one great land of Brettan, and the Never Lands fed an empire, before the Quiet Sea stole them. But the waters rose and a thousand cities drowned.’

‘And you think the oceans ready themselves for another bite?’ I grinned and held a hand out to accept the rain. ‘Will it pour for forty days and nights?’

‘Have you had a vision?’ A question rasped from scorched lungs. Red Kent had come to squat beside Gomst’s chair. Since surviving the inferno at the Haunt Sir Kent had got himself a bad case of religion.

‘It seems I chose well when making court in the mountains,’ I said. ‘Perhaps the Highland will become the richest island kingdom in the new world.’

Sir Riccard laughed at that. I seldom made a joke that didn’t find an echo in him. Makin twisted a grin. I trusted that more.

‘I speak of a different rising, a darker tide,’ Gomst said. He seemed determined to play the prophet. ‘Word comes from every convent, from Arrow, Belpan, Normardy, from the cold north and from the Port kingdoms. The most pious of the faith’s nuns dream of it. Hermits leave their caves to speak of what the night brings them, icons bleed to testify the truth. The Dead King readies himself. Black ships wait at anchor. The graves empty.’

‘We have fought the dead before, and won.’ The rain felt cold now.

‘The Dead King has overwhelmed the last of Brettan’s lords, he holds all the Isles. He has a fleet waiting to sail. The holiest see a black tide coming.’ Gomst looked up now, meeting my eyes.

‘Have you seen this, Gomst?’ I asked him.

‘I am not holy.’

That convinced me, of his belief and fear at least. I knew Gomst for a rogue, a goat-bearded letch with an eye for his own comfort and a taste for grand but empty oratory. Honesty from him spoke more than from another man.

‘You’ll come to Congression with me. Set this news before the Hundred.’

His eyes widened at that, rain stuttered from his lips. ‘I— I have no place there.’

‘You’ll come as one of my advisors,’ I told him. ‘Sir Riccard will cede his place to you.’

I stood, shaking the wet from my hair. ‘Damn this rain. Harran! Point me at my tent. Sir Kent, Riccard, see the bishop back to his church. I don’t want any ghoul or ghost troubling him on his return.’

Captain Harran had waited in the next fire circle and led me now to my pavilion, larger than the guards’, hide floors within, strewn with black and gold cushions. Makin followed in behind me, coughing and shaking off the rain, my bodyguard, though a pavilion had been set for him as Baron of Kennick. I shrugged off my cloak and it landed with a splat, leaking water.

‘Gomst sends us to bed with sweet dreams,’ I said, glancing around. A chest of provisions sat to my left and a commode had been placed on the opposite side. Silver lamps burning smokeless oil lit me to my bed, carved timber, four posted, assembled from pieces carried by a dozen different guards.

‘I’ve no faith in dreams.’ Makin set his cloak aside and shook like a wet dog. ‘Or the bishop.’

A chess set had been laid on a delicate table beside the bed, board of black and white marble, silver pieces, ruby-set or with emeralds to indicate the sides.

‘The guard lay their tents grander than my rooms at the Haunt,’ I said.

Makin inclined his head. ‘I don’t trust dreams,’ he repeated.

‘The women of Hodd Town wear no blues.’ I started to unbuckle my breastplate. I could have had a boy to do it, but servants are a disease that leaves you crippled.

‘You’re an observer of fashion now?’ Makin worked at his own armour, still dripping on the hides.

‘Tin prices are four times what they stood at when I took my uncle’s throne.’

Makin grinned. ‘Have I missed a guest? You’re speaking to somebody but it’s not me?’

‘That man of yours, Osser Gant? He would understand me.’ I let my armour lie where it fell. My eyes kept returning to the chessboard. They had set one for me on my last journey to Congression too. Every night. As if no one could pretend to the throne without being a player of the game.

‘You’ve led me to the water, but I can’t drink. Tell me plain, Jorg. I’m a simple man.’

‘Trade, Lord Makin.’ I pushed a pawn out experimentally. A ruby-eyed pawn, servant to the black queen. ‘We have no trade with the Isles, no tin, no woad, no Brettan nets, not those clever axes of theirs or those tough little sheep. We have no trade and black ships are seen off Conaught, sailing the Quiet Sea but never coming to port.’

‘There have been wars. The Brettan lords are always feuding.’ Makin shrugged.

‘Chella spoke of the Dead King. I don’t trust dreams but I trust the word of an enemy who thinks me wholly in their power. The marsh dead have kept my father’s armies busy on his borders. We would have had our reckoning years back, father and me, if he were not so tied with holding on to what he has.’

Makin nodded at that. ‘Kennick suffers too. All the men-at-arms who answer to me are set to keep the dead penned in the marshes. But an army of them? A king?’

‘Chella was a queen to the army she raised in the Cantanlona.’