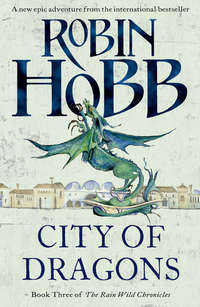

City of Dragons

Human shrieks and dragon roars culminated in a full-throated trumpeting from Mercor as he crashed into the knot of struggling males.

Sestican went down, bowled over by the impact. His spread wing bent dangerously as he rolled on it and she heard his huff of pain and dismay. Ranculos was trapped under the flailing Kalo. Kalo attempted to roll and meet Mercor with the longer claws of his powerful hind legs. But Mercor had reared onto his hind legs on top of the heap of struggling dragons. Suddenly he leapt forward and pinned Kalo’s wide-spread wings to the ground with his hind legs. A wild slash from the trapped dragon’s talons scored a gash down Mercor’s ribs, but before he could add another stripe of injury, Mercor shifted his stance higher. Kalo’s head and long neck lashed like a whip but Mercor clearly had the advantage. Trapped beneath the two larger dragons, Sestican roared in helpless fury. A thick stench of male dragon musk rose from the struggle.

A horde of frightened and angry keepers ringed the struggling dragons, shrieking and shouting the names of the combatants or attempting to keep other gawking dragons from joining the fray. The smaller females, Fente and Veras, had arrived and were craning their necks and ignoring their keepers as they ventured dangerously close. Baliper, scarlet tail lashing, prowled the outer edges of the conflict, sending keepers darting for safety, squeaking indignantly at the danger he presented.

The struggle ended almost as abruptly as it had begun. Mercor flung back his golden head and then snapped it forward, jaws wide. Screams from the keepers and startled roars from the watching dragons predicted Kalo’s death by acid spray. Instead, at the last moment, Mercor snapped his jaws shut. He darted his head down and spat, not a mist or a stream, but only a single blot of acid onto Kalo’s vulnerable throat. The blue-black dragon screamed in agony and fury. With three powerful beats of his wings, Mercor lifted off him and alighted a ship’s length away. Blood was running freely from the long gash on his ribs, sheeting down his gold-scaled side. He was breathing heavily, his nostrils flared wide. Colour rippled through his scales and the protective crests around his eyes stood tall. He lashed his tail and the smell of his challenge filled the air.

The moment Mercor had lifted his weight off him, Kalo had rolled to his feet. Snarling his frustration and humiliation, he headed immediately toward the river to wash the acid from his flesh before it could eat any deeper. Carson, Spit’s keeper, ran beside him, shouting at him to stop and let him look at the injury. The black dragon ignored him. Bruised and shaken but not much injured, Ranculos scrambled to his feet and staggered upright. He shook his wings out and then folded them slowly as if they were painful. Then, with what dignity he could muster, he limped away from the trampled earth of the combat site.

Mercor roared after the retreating Kalo. ‘Don’t forget that I could have killed you! Don’t ever forget it, Kalo!’

‘Lizard spawn!’ the dark dragon roared back at him but did not slow his retreat toward the icy waters of the river.

Sintara turned away from them. It was over. She was surprised it had lasted as long as it had. Battle, like mating, was something that dragons did on the wing. Had the males been able to take flight, the contest might have gone on for hours, perhaps the entire day, and left all of them acid-seared and bloodied. For a moment, her ancestral memories of such trials seized her mind and she felt her heart race with excitement. The males would have battled for her regard, and in the end, when only one was the victor, still he would have had to match her in flight and meet her challenge before he could claim the right to mate with her. They would have soared through air, going higher and higher as the drake sought to match her loops and dives and powerful climbs. And if he had succeeded, if he had managed to come close enough to match her flight, he would have locked his body to hers, and as their wings synchronized …

‘SINTARA!’

Mercor’s bellow startled her out of her reflection. She was not the only one who turned to see what the gold drake wanted of her. Every dragon and keeper on the meadow was staring at him. And at her.

The great golden dragon lifted his head and then snapped opened his wings with an audible crack. A fresh wave of his scent went out on the wind. ‘You should not provoke what you cannot complete,’ he rebuked her.

She stared at him, feeling anger flush her colours brighter. ‘It had nothing to do with you, Mercor. Perhaps you should not intrude into things that do not concern you.’

He spread his wings wider still, and lifted his body tall on his powerful hind legs. ‘I will fly.’ He did not roar the words, but even so they still carried clearly through the wind and rain. ‘As will you. And when the time comes for mating battles, I will win. And I will mate you.’

She stared at him, more shocked than she had thought she could be. Unthinkable for a male to make such a blatant claim. She tried not to be flattered that he had said she would fly. When the silence grew too long, when she became aware that everyone was watching her, expecting a response, she felt anger. ‘So say you,’ she retorted lamely. She did not need to hear Fente’s snort of disdain to know that her feeble response had impressed no one.

Turning away from them all, she began stalking back to the forest and the thin shelter of the trees. She didn’t care. She didn’t care what Mercor had said nor that Fente had mocked her. There was none among them worth impressing. ‘Scarcely a proper battle at all,’ she sneered quietly.

‘Was a “proper battle” what you were trying to provoke?’ Her snippy little keeper Thymara was abruptly beside her, trotting to keep up. Her black hair hung in fuzzy, tattered braids, a few still adorned with wooden charms. Her roll down the hill had coated her ragged cloak with dead grass. Her feet were bound up in mismatched rags, the make-shift shoes soled with crudely-tanned deerskin. She had grown thinner of late, and taller. The bones of her face stood out more. The wings that Sintara had gifted her with bounced lightly beneath her cloak as she jogged. Despite the rudeness of her first query, Thymara sounded concerned as she added, ‘Stop a moment. Crouch down. Let me see your neck where he bit you.’

‘He didn’t draw blood.’ Sintara could scarcely believe she was answering such an impudent demand from a mere human.

‘I want to look at it. It looks as if several scales are loosened.’

‘I did nothing to provoke that silly squabble.’ Sintara halted abruptly and lowered her head so that Thymara could inspect her neck. She resented doing it, feeling that she had somehow given way to the human’s domineering manner. Anger simmered in her. Briefly she considered ‘accidentally’ knocking Thymara off her feet with a swipe of her head. But as she felt the girl’s strong hands gently easing her misaligned neck scales back into smoothness, she relented. Her keeper and her clever hands had their uses.

‘None of the scales are torn all the way free, though you may shed some of them sooner rather than later.’

Sintara sensed her keeper’s annoyance as she set her scales to rights. Despite Thymara’s frequent rudeness to Sintara, the dragon knew the girl took pride in her health and appearance. Any insult to Sintara rankled Thymara as well. And she would be aware of her dragon’s mood, too.

As she focused more on the girl, she knew that they shared more than annoyance. The frustration was there as well. ‘Males!’ the girl exclaimed suddenly. ‘I suppose it takes no more to provoke a male dragon to stupidity than it does a human male.’

Sintara’s curiosity was stirred by the comment, though she would not let Thymara know that. She reviewed what she knew of Thymara’s most recent upsets and divined the source of her sour mood. ‘The decision is yours, not theirs. How foolishly you are behaving! Just mate with both of them. Or neither. Show them that you are a queen, not a cow to be bred at the bull’s rutting.’

‘I chose neither,’ Thymara told her, answering the question that the dragon hadn’t asked.

Her scales smoothed, Sintara lifted her head and resumed her trek to the forest’s edge. Thymara hurried to stay beside her, musing as she jogged. ‘I just want to let it alone, to leave things as they’ve always been. But neither of them seems willing to let that happen.’ She shook her head, her braids flying with the motion. ‘Tats is my oldest friend. I knew him back in Trehaug, before we became dragon keepers. He’s part of my past, part of home. But when he pushes me to bed with him, I don’t know if it’s because he loves me, or simply because I’ve refused him. I worry that if we become lovers and it doesn’t work out, I’ll lose him completely.’

‘Then bed Rapskal and be done with it,’ the dragon suggested. Thymara was boring her. How could humans seriously believe that a dragon could be interested in the details of their lives? As well worry about a moth or a fish.

The keeper took the dragon’s comment as an excuse to keep talking. ‘Rapskal? I can’t. If I take him as a mate, I know that would ruin my friendship with Tats. Rapskal is handsome, and funny … and a bit strange. But it’s a sort of strange that I like. And I think he truly cares about me, that when he pushes me to sleep with him, it’s not just for the pleasure.’ She shook her head. ‘But I don’t want it, with either of them. Well, I do. If I could just have the physical part of it, and not have it make everything else complicated. But I don’t want to take the chance of catching a child, and I don’t really want to have to make some momentous decision. If I choose one, have I lost the other? I don’t know what—’

‘You’re boring me,’ Sintara warned her. ‘And there are more important things you should be doing right now. Have you hunted for me today? Do you have meat to bring me?’

Thymara bridled at the sudden change of topic. She replied grudgingly, ‘Not yet. When the rain lets up, I’ll go. There’s no game moving right now.’ A pause, and then she broached another dangerous subject. ‘Mercor said you would fly. Were you trying? Have you exercised your wings today, Sintara? Working on the muscles is the only way that you will ever—’

‘I have no desire to flap around on the beach like a gull with a broken wing. No desire to make myself an object of mockery.’ Even less desire to fail and fall into the icy, swift-flowing river and drown. Or over-estimate her skills and plummet into the trees as Baliper had done. His wings were so swollen that he could not close them, and he’d torn a claw from his left front foot.

‘No one mocks you! Exercising your wings is a necessity, Sintara. You must learn to fly; all of the dragons must. You all have grown since we left Cassarick, and it is becoming impossible for me to kill enough game to keep you well fed, even with the larger game that we’ve found here. You will have to hunt for your own food, and to do that, you must be able to fly. Would not you rather be one of the first dragons to leave the ground than one of the last ones?’

That thought stung. The idea that the smaller females such as Veras or Fente might gain the air before she did was intolerable. It might actually be easier for such stunted and scrawny creatures to fly. Anger warmed her blood and she knew the liquid copper of her eyes would be swirling with emotion. She’d have to kill them, that was all. Kill them before either one could humiliate her.

‘Or you could take flight before they did,’ Thymara suggested steadily.

Sintara snapped her head around to stare at the girl. Sometimes she was able to overhear the dragon’s thoughts. Sometimes she was even impudent enough to answer them.

‘I’m tired of the rain. I want to go back under the trees.’

Thymara nodded and as Sintara stalked off, she followed docilely. The dragon looked back only once.

Down by the river, other keepers were stridently discussing which dragon had started the melee. Carson the hunter had his arms crossed and stood in stubborn confrontation with Kalo. The black dragon was dripping; he’d rinsed Mercor’s acid from this throat, then. Carson’s small silver dragon, Spit, was watching them sullenly from a distance. The man was stupid, Sintara thought. The big blue-black male was not fond of humans to start with: provoked, Kalo might simply snap Carson in two.

Tats was helping Sylve examine the long injury down Mercor’s ribs while his own dragon, Fente, jealously clawed at the mud and muttered vague threats. Ranculos was holding one wing half-opened for his keeper’s inspection. It was likely badly bruised at the very least. Sestican, covered in mud, was dispiritedly bellowing for his keeper but Lecter was nowhere in sight. The squabble was over. For one moment, they had been dragons, vying for the attention of a female. Now they were back to behaving like large cattle. She despised them, and she loathed herself. They weren’t worth her time to provoke. They only made her think of all they were not. All she was not.

If only, she thought, and traced her misfortune back, happenstance after happenstance. If only the dragons had emerged from the metamorphosis fully-formed and healthy. If only they had been in better condition when they cocooned to make the transition from sea serpent to dragon. If only they had migrated home decades ago. If only the Elderlings had not died off, if only the mountain had never erupted and put an end to the world they had once known. She should have been so much more than she was. Dragons were supposed to emerge from their cocoons capable of flight, and take wing to make that first rejuvenating kill. But none of them had. She was like a bright chip of glass, fallen from a gorgeous mosaic of Elderlings and turreted cities and dragons on the wing, to lie in the dirt, broken away from all she that had once been her destiny. She was meaningless without that world.

She had tried to fly, more than once. Thymara need never know of her many private and humiliating failures. It was infuriating that dim-witted Heeby was able to take flight and hunt for herself. Every day, the red female grew larger and stronger, and her keeper Rapskal never tired of singing the praises of his ‘great, glorious girl’ of a dragon. He’d made up a stupid song, more doggerel than poetry, and loudly sang it to her every morning as he groomed her. It made Sintara want to bite his head off. Heeby could preen all she liked when her keeper sang to her. She was still dumber than a cow.

‘The best vengeance might be to learn to fly,’ Thymara suggested again, privy to the feeling rather than the thought.

‘Why don’t you try that yourself?’ Sintara retorted bitterly.

Thymara was silent, a silence that simmered.

The idea came to Sintara slowly. She was startled. ‘What? You have, haven’t you? You’ve tried to fly?’

Thymara kept her face turned away from the dragon as they trudged through the wild meadow and up toward the tree line. Scattered throughout the meadow were small stone cottages, some little more than broken walls and collapsed roofs while others had been restored by the dragon keepers. Once there had been a village here, a place for human artisans to live. They’d plied their trades here, the servant and merchant classes of the Elderlings who had lived in the gleaming city on the far side of the swift-flowing river. She wondered if Thymara knew that. Probably not.

‘You made these wings grow on me,’ Thymara finally replied. ‘If I have to have them, if I have to put up with something that makes it impossible to wear an ordinary shirt, something that lifts my cloak up off my back so that every breeze chills me, then I might as well make them useful. Yes, I’ve tried to fly. Rapskal was helping me. He insists I’ll be able to, one day. But so far all I’ve done is skin my knees and scrape the palms of my hands when I fall. I’ve had no success. Does that please you?’

‘It doesn’t surprise me.’ It did please her. No human should fly when dragons could not! Let her skin her knees and bruise herself a thousand times. If Thymara took flight before she did, the dragon would eat her! Her hunger stirred at the thought and she became sensible. There was no sense in making the girl aware of that, at least not until she’d done her day’s hunting.

‘I’m going to keep trying,’ Thymara said in a low voice. ‘And so should you.’

‘Do as you please and I’ll do the same,’ the dragon replied. ‘And what should please you right now is that you go hunting. I’m hungry.’ She gave the girl a mental push.

Thymara narrowed her eyes, aware that the dragon had used her glamour on her. It didn’t matter. She would still be nagged with an urgent desire to go hunting. Being aware of the source of that suggestion would not make her immune to it.

The winter rains had prompted an explosion of greenery. The tall wet grasses slapped against her legs as they waded through it. They had climbed the slope of the meadow and now the open forest of the hillside beckoned. Beneath the trees, there would be some shelter from the rain, although many of the trees here had lost their foliage. The forest seemed both peculiar and familiar to Sintara. Her own life’s experience had been limited to the dense and impenetrable forest that bordered the Rain Wilds River. Yet her ancestral memories echoed the familiarity of woods such as this. The names of the trees – oak and hickam and birch, alder and ash and goldleaf – came to her mind. Dragons had known these trees, this sort of forest and even this particular place. But they had seldom lingered here in the chill rains of winter. No. For this miserable season, dragons would have flown off to bask in the heat of the deserts. Or they would have taken shelter in the places that the Elderlings created for them, crystal domes with heated floors and pools of steaming water. She turned and looked across the river to fabled Kelsingra. They had come so far, and yet asylum remained out of reach. The swift-flowing river was deep and treacherous. No dragon could swim it. True flight was the only way home.

The ancient Elderling city stood, mostly intact, just as her ancestral memories had recalled it. Even under the overcast, even through the grey onslaught of rain, the towering buildings of black and silver stone gleamed and beckoned. Once, lovely scaled Elderlings had resided there. Friends and servants of dragons, they had dressed in bright robes and adorned themselves with gold and silver and gleaming copper. The wide avenues of Kelsingra and the gracious buildings had all been constructed to welcome dragons as well as Elderlings. There had been a statuary plaza, where the flagstones radiated heat in the winter, though that area of the city appeared to have vanished into the giant chasm that now cleft its ancient roads and towers. There had been baths, steaming vats of hot water where Elderlings and dragons alike had taken refuge from foul weather. Her ancestors had soaked there, not just in hot water, but in copper vats of simmering oils that had sheened their scales and hardened their claws.

And there had been … something else. Something she could not quite recall clearly. Water, she thought, but not water. Something delightful, something that even now sparkled and gleamed and called to her through her dim recollection of it.

‘What are you looking at?’ Thymara asked her.

Sintara hadn’t realized that she had halted to stare across the river. ‘Nothing. The city,’ she said and resumed her walk.

‘If you could fly, you could get across the river to Kelsingra.’

‘If you could think, you would know when to be quiet,’ the dragon retorted. Did the stupid girl not realize how often she thought of that? Daily. Hourly. The Elderling magic of heated tiles might still work. Even if it did not, the standing buildings would provide shelter from the incessant rain. Perhaps in Kelsingra she would feel like a real dragon again rather than a footed serpent.

They reached the edge of the trees. A gust of wind rattled them, sending water spattering down through the sheltering branches. Sintara rumbled her displeasure. ‘Go hunt,’ she told the girl, and strengthened her mental push.

Offended, her keeper turned away and trudged back down the hill. Sintara didn’t bother to watch her go. Thymara would obey. It was what keepers did. It was really all they were good for.

‘Carson!’

The hunter held up a cautioning hand, palm open, toward Sedric. Carson stood his ground, staring up at the blue-black dragon. He was not speaking but had locked gazes with the creature. Carson was not a small man, but Kalo dwarfed him to the size of a toy. A toy the infuriated dragon could trample into the earth, or melt to hollowed bones with a single blast of acid-laced venom. And Sedric would be able to do nothing about it. His heart hammered in his chest and he felt he could not get his breath. He hugged himself, shivering with the chill day and with his fear. Why did Carson have to take such risks with himself?

I will protect you. Sedric’s own dragon, Relpda, nudged him with her blunt nose and her thoughts.

He turned quickly to put a restraining hand on her neck as he tried to force calm on his own thoughts. The little copper female would not stand a chance if she challenged Kalo on Sedric’s behalf. And any challenge to Kalo right now would probably provoke an irrational and violent response. Sedric was not Kalo’s keeper, but he felt the dragon’s emotions. The waves of anger and frustration that radiated from the black dragon would have affected anyone.

‘Let’s step back a bit,’ he suggested to the copper, and pushed on her. She didn’t budge. When he looked at her, her eyes seemed to spin, dark blue with an occasional thread of silver in them. She had decided Kalo was a danger to him. Oh, dear.

Carson was speaking now, firmly, without anger. His muscled arms were crossed on his chest, offering no threat. His dark eyes under his heavy brows were almost kind. The wet wind tugged at his hair and left drops clinging to his trimmed ginger beard. The hunter ignored the wind and rain as he ignored the dragon’s superior strength. He seemed to have no fear of Kalo or the dragon’s suppressed fury. Carson’s voice was deep and calm, his words slow. ‘You need to calm down, Kalo. I’ve sent one of the others to find Davvie. Your own keeper will be here soon, to tend your hurts. If you wish, I will look at them now. But you have to stop threatening everyone.’

The blue-black dragon shifted and scintillations of silver glittered over his scaling in the rain. The colours in his eyes melted and swirled to the green of copper ore; it looked as if his eyes were spinning. Sedric stared at them with fascination tinged with horror. Carson was too close. The creature looked no calmer to him, and if he chose to snap at Carson or spit acid at him, even the hunter’s agility would not be enough to save him from death. Sedric drew breath to plead with him to step back, and then gritted his teeth together. No. Carson knew what he was doing and the last thing he needed now was a distraction from his lover.

Sedric heard running feet behind him and turned to see Davvie pelting toward them as fast as he could. The young keeper’s cheeks were bright red with effort and his hair bounced around his face and shoulders. Lecter trundled along in his wake though the soaked meadow grass, looking rather like a damp hedgehog. The spines on the back of his neck were becoming a mane down his back, twin to the ones on his dragon, Sestican. Lecter could no longer contain them in a shirt. They were blue, tipped with orange, and they bobbed as he tried to keep up with Davvie, panting loudly. Davvie dragged in a breath and shouted, ‘Kalo! Kalo, what’s wrong? I’m here, are you hurt? What happened?’

Lecter veered off, headed toward Sestican. ‘Where were you?’ his dragon trumpeted, angry and querulous. ‘Look, I am filthy and bruised. And you did not attend me.’

Davvie raced right up to his huge dragon with a fine disregard for how angry the beast was. From the moment the boy had appeared, Kalo’s attention had been fixed only on him. ‘Why weren’t you here to attend me?’ the dragon bellowed accusingly. ‘See how I am burned! Your carelessness could have cost me my life!’ The dragon flung up his head to expose the raw circle on this throat where Mercor’s acid had scored him. It was the size of a saucer.