The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1808)

The words were very apt to my case, and made some impression upon my thoughts at the time of reading them, though not so much as they did afterwards; for as for being delivered, the word had no sound, as I may say, to me; the thing was so remote, so impossible in my apprehension of things, that I began to say as the children of Israel did, when they were promised flesh to eat, "Can God spread a table in the wilderness?" So I began to say, Can God himself deliver me from this place? And as it was not for many years that any hope appeared, this prevailed very often upon my thoughts: but, however, the words made a very great impression upon me, and I mused upon them very often. It grew now late, and the tobacco had, as I said, dozed my head so much, that I inclined to sleep; so that I left my lamp burning in the cave, lest I should want any thing in the night, and went to bed; but before I lay down, I did what I never had done in all my life: I kneeled down, and prayed to God to fulfil the promise to me, that if I called upon him in the day of trouble, he would deliver me. After my broken and imperfect prayer was over, I drank the rum in which I had steeped the tobacco, which was so strong and rank of the tobacco, that indeed I could scarce get it down. Immediately upon this I went to bed, and I found presently it flew up into my head violently; but I fell into a sound sleep, and waked no more, till by the sun it must necessarily be near three o'clock in the afternoon the next day; nay, to this hour I am partly of the opinion, that I slept all the next day and night, and till almost three the day after; for otherwise I knew not how I should lose a day out of my reckoning in the days of the week, as it appeared some years after I had done; for if I had lost it by crossing and recrossing the line, I should have lost more than a day; but in my account it was lost, and I never knew which way.

Be that however one way or other; when I awaked, I found myself exceedingly refreshed, and my spirits lively and cheerful; when I got up, I was stronger than I was the day before, and my stomach better; for I was hungry; and, in short, I had no fit the next day, but continued much altered for the better: this was the 29th.

The 30th was my well day of course, and I went abroad with my gun, but did not care to travel too far: I killed a sea-fowl or two, something like a brand goose, and brought them home, but was not very forward to eat them: so I ate some more of the turtle's eggs, which were very good. This evening I renewed the medicine which I had supposed did me good the day before, viz. the tobacco steeped in rum; only I did not take so much as before, nor did I chew any of the leaf, or hold my head over the smoke; however, I was not so well the next day, which was the 1st of July, as I hoped I should have been; for I had a little spice of the cold fit, but it was not much.

July 2. I renewed the medicine all the three ways, and dozed myself with it at first, and doubled the quantity which I drank.

July 3. I missed the fit for good and all, though I did not recover my full strength for some weeks after. While I was thus gathering strength, my thoughts ran exceedingly upon this scripture, "I will deliver thee;" and the impossibility of my deliverance lay much upon my mind, in bar of my ever expecting it: but as I was discouraging myself with such thoughts, it occurred to my mind, that I pored so much upon my deliverance from the main affliction, that I disregarded the deliverance I had received; and I was, as it were, made to ask myself such questions as these; viz. Have I not been delivered, and wonderfully too, from sickness? from the most distressed condition that could be, and that was so frightful to me? and what notice had I taken of it? had I done my part? God had delivered me; but I had not glorified him: that is to say, I had not owned and been thankful for that as a deliverance; and how could I expect greater deliverance?

This touched my heart very much, and immediately I kneeled down, and gave God thanks aloud, for my recovery from my sickness.

July 4. In the morning I took the Bible; and, beginning at the New Testament, I began seriously to read it, and imposed upon myself to read a while every morning and every night, not tying myself to the number of chapters, but as long as my thoughts should engage me. It was not long after I set seriously to this work, but I found my heart more deeply and sincerely affected with the wickedness of my past life; the impression of my dream revived, and the words, "All these things have not brought thee to repentance," ran seriously in my thoughts: I was earnestly begging of God to give me repentance, when it happened providentially the very day, that, reading the Scripture, I came to these words, "He is exalted a Prince, and a Saviour, to give repentance, and to give remission." I threw down the book, and with my heart as well as my hand lifted up to heaven, in a kind of ecstasy of joy, I cried out aloud, "Jesus, thou Son of David, Jesus, thou exalted Prince and Saviour, give me repentance!"

This was the first time that I could say, in the true sense of the words, that I prayed in all my life; for now I prayed with a sense of my condition, and with a true Scripture view of hope, founded on the encouragement of the word of God; and from this time, I may say, I began to have hope that God would hear me.

Now I began to construe the words mentioned above, "Call on me, and I will deliver thee," in a different sense from what I had ever done before; for then I had no notion of any thing being called deliverance, but my being delivered from the captivity I was in; for though I was indeed at large in the place, yet the island was certainly a prison to me, and that in the worst sense in the world; but now I learnt to take it in another sense. Now I looked back upon my past life with such horror, and my sins appeared so dreadful, that my soul sought nothing of God, but deliverance from the load of guilt that bore down all my comfort. As for my solitary life, it was nothing; I did not so much as pray to be delivered from it, or think of it; it was all of no consideration in comparison of this; and I added this part here, to hint to whoever shall read it, that whenever they come to a true sense of things, they will find deliverance from sin a much greater blessing than deliverance from affliction.

But, leaving this part, I return to my journal. My condition began now to be, though not less miserable as to my way of living, yet much easier to my mind; and my thoughts being directed, by a constant reading the Scripture, and praying to God, to things of a higher nature, I had a great deal of comfort within, which till now I knew nothing of; also as my health and strength returned, I bestirred myself to furnish myself with every thing that I wanted, and make my way of living as regular as I could.

From the 4th of July to the 14th, I was chiefly employed in walking about with my gun in my hand a little and a little at a time, as a man that was gathering up his strength after a fit of sickness; for it is hardly to be imagined how low I was, and to what weakness I was reduced. The application which I made use of was perfectly new, and perhaps what had never cured an ague before; neither can I recommend it to any one to practise by this experiment; and though it did carry off the fit, yet it rather contributed to weaken me; for I had frequent convulsions in my nerves and limbs for some time.

I learnt from it also this in particular, that being abroad in the rainy season was the most pernicious thing to my health that could be, especially in those rains which came attended with storms and hurricanes of wind; for as the rain which came in a dry season was always most accompanied with such storms, so I found this rain was much more dangerous than the rain which fell in September and October.

I had been now in this unhappy island above ten months; all possibility of deliverance from this condition seemed to be entirely taken from me; and I firmly believed that no human shape had ever set foot upon that place. Having now secured my habitation, as I thought, fully to my mind, I had a great desire to make a more perfect discovery of the island, and to see what other productions I might find, which yet I knew nothing of.

It was the 15th of July that I began to take a more particular survey of the island itself. I went up the creek first, where, as I hinted, I brought my rafts on shore. I found, after I came about two miles up, that the tide did not flow any higher, and that it was no more than a little brook of running water, and very fresh and good: but this being the dry season, there was hardly any water in some parts of it, at least not enough to run into any stream, so as it could be perceived.

On the bank of this brook I found many pleasant savannas or meadows, plain, smooth, and covered with grass; and on the rising parts of them next to the higher grounds, where the water, as it might be supposed, never overflowed, I found a great deal of tobacco, green, and growing to a great and very strong stalk: there were divers other plants which I had no notion of, or understanding about; and might perhaps have virtues of their own, which I could not find out.

I searched for the cassave root, which the Indians in all that climate make their bread of, but I could find none. I saw large plants of aloes, but did not then understand them: I saw several sugar-canes, but wild, and, for want of cultivation, imperfect. I contented myself with these discoveries for this time, and came back, musing with myself what course I might take to know the virtue and goodness of any of the fruits or plants which I should discover, but could bring it to no conclusion; for, in short, I had made so little observation while I was in the Brasils, that I knew little of the plants of the field, at least very little that might serve me to any purpose now in my distress.

The next day, the 16th, I went up the same way again; and, after going something farther than I had done the day before, I found the brook and the savannas began to cease, and the country became more woody than before. In this part I found different fruits, and particularly I found melons upon the ground in great abundance, and grapes upon the trees; the vines had spread indeed over the trees, and the clusters of grapes were just now in their prime, very ripe and rich. This was a surprising discovery, and I was exceeding glad of them; but I was warned by my experience to eat sparingly of them, remembering, that when I was ashore in Barbary, the eating of grapes killed several of our Englishmen who were slaves there, by throwing them into fluxes and fevers: but I found an excellent use for these grapes, and that was to cure or dry them in the sun, and keep them as dried grapes or raisins are kept, which I thought would be, as indeed they were, as wholesome, and as agreeable to eat, when no grapes might be had.

I spent all that evening there, and went not back to my habitation, which by the way was the first night, as I might say, I had lain from home. In the night I took my first contrivance, and got up into a tree, where I slept well, and the next morning proceeded upon my discovery, travelling near four miles, as I might judge by the length of the valley, keeping still due north, with a ridge of hills on the south and north side of me.

At the end of this march I came to an opening, where the country seemed to descend to the west; and a little spring of fresh water, which issued out of the side of the hill by me, ran the other way, that is, due east; and the country appeared so fresh, so green, so flourishing, every thing being in a constant verdure or flourish of spring, that it looked like a planted garden.

I descended a little on the side of that delicious valley, surveying it with a secret kind of pleasure (though mixed with other afflicting thoughts) to think that this was all my own, that I was king and lord of all this country indefeasibly, and had a right of possession; and if I could convey it, I might have it in inheritance, as completely as any lord of a manor in England. I saw here abundance of cocoa-trees, orange and lemon, and citron-trees, but all wild, and few bearing any fruit; at least, not then: however, the green limes that I gathered were not only pleasant to eat, but very wholesome; and I mixed their juice afterwards with water, which made it very wholesome, and very cool and refreshing.

I found now I had business enough to gather and carry home; and resolved to lay up a store, as well of grapes as limes and lemons, to furnish myself for the wet season, which I knew was approaching.

In order to do this I gathered a great heap of grapes in one place, and a lesser heap in another place, and a great parcel of limes and lemons in another place; and taking a few of each with me, I travelled homeward, and resolved to come again, and bring a bag or sack, or what I could make, to carry the rest home.

Accordingly, having spent three days in this journey, I came home (so I must now call my tent, and my cave;) but before I got thither, the grapes were spoiled; the richness of the fruit, and the weight of the juice, having broken them, and bruised them, they were good for little or nothing: as to the limes, they were good, but I could bring but a few.

The next day, being the 19th, I went back, having made me two small bags to bring home my harvest. But I was surprised, when coming to my heap of grapes, which were so rich and fine when I gathered them, I found them all spread abroad, trod to pieces, and dragged about, some here, some there, and abundance eaten and devoured. By this I concluded there were some wild creatures thereabouts, which had done this; but what they were I knew not.

However, as I found there was no laying them up on heaps, and no carrying them away in a sack, but that one way they would be destroyed, and the other way they would be crushed with their own weight, I took another course; for I gathered a large quantity of the grapes, and hung them upon the out branches of the trees, that they might cure and dry in the sun; and as for the limes and lemons, I carried as many back as I could well stand under.

When I came home from this journey, I contemplated with great pleasure on the fruitfulness of that valley, and the pleasantness of the situation, the security from storms on that side of the water, and the wood; and concluded that I had pitched upon a place to fix my abode, which was by far the worst part of the country. Upon the whole, I began to consider of removing my habitation, and to look out for a place equally safe as where I now was situated, if possible, in that pleasant fruitful part of the island.

This thought ran long in my head, and I was exceeding fond of it for some time, the pleasantness of the place tempting me; but when I came to a nearer view of it, and to consider that I was now by the sea-side, where it was at least possible that something might happen to my advantage, and that the same ill fate that brought me hither might bring some other unhappy wretches to the same place; and though it was scarce probable that any such thing should ever happen, yet to enclose myself among the hills and woods, in the centre of the island, was to anticipate my bondage, and to render such an affair not only improbable, but impossible; and that therefore I ought not by any means to remove.

However, I was so enamoured with this place, that I spent much of my time there for the whole remaining part of the month of July; and though, upon second thoughts, I resolved as above, not to remove, yet I built me a little kind of a bower, and surrounded it at a distance with a strong fence, being a double hedge, as high as I could reach, well staked and filled between with brushwood; and here I lay very secure, sometimes two or three nights together, always going over it with a ladder, as before; so that I fancied now I had my country house, and my sea-coast house: and this work took me up the beginning of August.

I had but newly finished my fence, and began to enjoy my labour, but the rains came on, and made me stick close to my first habitation; for though I had made me a tent like the other, with a piece of a sail, and spread it very well, yet I had not the shelter of a hill to keep me from storms, nor a cave behind me to retreat into when the rains were extraordinary.

About the beginning of August, as I said, I had finished my bower, and began to enjoy myself. The 3d of August I found the grapes I had hung up were perfectly dried, and indeed were excellent good raisins of the sun; so I began to take them down from the trees, and it was very happy that I did so; for the rains which followed would have spoiled them, and I had lost the best part of my winter food; for I had above two hundred large bunches of them. No sooner had I taken them all down, and carried most of them home to my cave, but it began to rain; and from thence, which was the 14th of August, it rained more or less every day, till the middle of October; and sometimes so violently, that I could not stir out of my cave for several days.

In this season I was much surprised with the increase of my family: I had been concerned for the loss of one of my cats, who ran away from me, or, as I thought, had been dead; and I heard no more tale or tidings of her, till to my astonishment she came home about the end of August, with three kittens. This was the more strange to me, because though I had killed a wild cat, as I called it, with my gun, yet I thought it was a quite different kind from our European cats; yet the young cats were the same kind of house breed like the old one; and both my cats being females, I thought it very strange: but from these three cats I afterwards came to be so pestered with cats, that I was forced to kill them like vermin, or wild beasts, and to drive them from my house as much as possible.

From the 14th of August to the 26th, incessant rain, so that I could not stir, and was now very careful not to be much wet. In this confinement I began to be straitened for food; but venturing out twice, I one day killed a goat: and the last day, which was the 26th, found a very large tortoise, which was a treat to me, and my food was regulated thus: I ate a bunch of raisins for my breakfast, a piece of the goat's flesh, or of the turtle, for my dinner, broiled (for, to my great misfortune, I had no vessel to boil or stew any thing;) and two or three of the turtle's eggs for supper. During this confinement in my cover by the rain, I worked daily two or three hours at enlarging my cave; and, by degrees, worked it on towards one side, till I came to the outside of the hill, and made a door or way out, which came beyond my fence or wall; and so I came in and out this way: but I was not perfectly easy at lying so open; for as I had managed myself before, I was in a perfect enclosure, whereas now I thought I lay exposed; and yet I could not perceive that there was any living thing to fear, the biggest creature that I had seen upon the island being a goat.

September the 30th. I was now come to the unhappy anniversary of my landing: I cast up the notches on my post, and found I had been on shore three hundred and sixty-five days. I kept this day as a solemn fast, setting it apart to a religious exercise, prostrating myself to the ground with the most serious humiliation, confessing myself to God, acknowledging his righteous judgment upon me, and praying to him to have mercy on me, through Jesus Christ; and having not tasted the least refreshment for twelve hours, even till the going down of the sun, I then ate a biscuit-cake and a bunch of grapes, and went to bed, finishing the day as I began it.

I had all this time observed no sabbath-day; for as at first I had no sense of religion upon my mind, I had after some time omitted to distinguish the weeks, by making a longer notch than ordinary for the sabbath-day, and so did not really know what any of the days were; but now, having cast up the days as before, I found I had been there a year; so I divided it into weeks, and set apart every seventh day for a sabbath; though I found at the end of my account I had lost a day or two of my reckoning.

A little after this my ink began to fail me, and so I contented myself to use it more sparingly, and to write down only the most remarkable events of my life, without continuing a daily memorandum of other things.

The rainy season, and the dry season, began now to appear regular to me, and I learnt to divide them so as to provide for them accordingly. But I bought all my experience before I had it; and this I am going to relate, was one of the most discouraging experiments that I made at all. I have mentioned, that I had saved the few ears of barley and rice which I had so surprisingly found spring up, as I thought, of themselves, and believe there were about thirty stalks of rice, and about twenty of barley: and now I thought it a proper time to sow it after the rains, the sun being in its southern position going from me.

Accordingly I dug up a piece of ground, as well as I could, with my wooden spade, and dividing it into two parts, I sowed my grain; but as I was sowing, it casually occurred to my thought, that I would not sow it all at first, because I did not know when was the proper time for it; so I sowed about two thirds of the seeds, leaving about a handful of each.

It was a great comfort to me afterwards that I did so; for not one grain of that I sowed this time came to any thing; for the dry months following, the earth having had no rain after the seed was sown, it had no moisture to assist its growth, and never came up at all, till the wet season had come again, and then it grew as if it had been newly sown.

Finding my first seed did not grow, which I easily imagined was by the drought, I sought for a moister piece of ground to make another trial in; and I dug up a piece of ground near my new bower, and sowed the rest of my seed in February, a little before the vernal equinox; and this, having the rainy months of March and April to water it, sprung up very pleasantly, and yielded a very good crop; but having part of the seed left only, and not daring to sow all that I had yet, I had but a small quantity at last, my whole crop not amounting to above half a peck of each kind.

But by this experience I was made master of my business, and knew exactly when the proper season was to sow; and that I might expect two seed-times, and two harvests, every year.

While this corn was growing, I made a little discovery, which was of use to me afterwards. As soon as the rains were over, and the weather began to settle, which was about the month of November, I made a visit up the country to my bower, where though I had not been some months, yet I found all things just as I left them. The circle or double hedge that I had made, was not only firm and entire, but the stakes which I had cut off of some trees that grew thereabouts, were all shot out, and grown with long branches, as much as a willow tree usually shoots the first year after lopping its head. I could not tell what tree to call it that these stakes were cut from. I was surprised, and yet very well pleased, to see the young trees grow; and I pruned them, and led them up to grow as much alike as I could; and it is scarce credible, how beautiful a figure they grew into in three years; so that though the hedge made a circle of about twenty-five yards in diameter, yet the trees, for such I might now call them, soon covered it; and it was a, complete shade, sufficient to lodge under all the dry season.

This made me resolve to cut some more stakes, and make me an hedge like this in a semicircle round my wall, I mean that of my first dwelling, which I did; and placing the trees or stakes in a double row, at above eight yards distance from my first fence, they grew presently, and were at first a fine cover to my habitation, and afterwards served for a defence also, as I shall observe in its order.

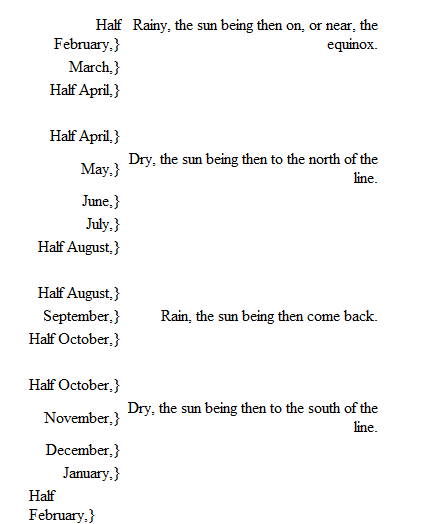

I found now, that the seasons of the year might generally be divided, not into summer and winter, as in Europe, but into the rainy seasons and the dry seasons, which were generally thus:

The rainy season sometimes held longer or shorter, as the winds happened to blow; but this was the general observation I made. After I had found, by experience, the ill consequence of being abroad in the rain, I took care to furnish myself with provision beforehand, that I might not be obliged to go out; and I sat within doors as much as possible during the wet months.