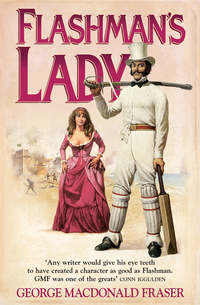

Flashman’s Lady

It may strike you that old Flashy’s approach to our great summer game wasn’t quite that of your school-storybook hero, apple-cheeked and manly, playing up unselfishly for the honour of the side and love of his gallant captain, revelling in the jolly rivalry of bat and ball while his carefree laughter rings across the green sward. No, not exactly; personal glory and cheap wickets however you could get ’em, and d--n the honour of the side, that was my style, with a few quid picked up in side-bets, and plenty of skirt-chasing afterwards among the sporting ladies who used to ogle us big hairy fielders over their parasols at Canterbury Week. That’s the spirit that wins matches, and you may take my word for it, and ponder our recent disastrous showing against the Australians while you’re about it.1

Of course, I speak as one who learned his cricket in the golden age, when I was a miserable fag at Rugby, toadying my way up the school and trying to keep a whole skin in that infernal jungle – you took your choice of emerging a physical wreck or a moral one, and I’m glad to say I never hesitated, which is why I’m the man I am today, what’s left of me. I snivelled and bought my way to safety when I was a small boy, and bullied and tyrannised when I was a big one; how the d---l I’m not in the House of Lords by now, I can’t think. That’s by the way; the point is that Rugby taught me only two things really well, survival and cricket, for I saw even at the tender age of eleven that while bribery, fawning, and deceit might ensure the former, they weren’t enough to earn a popular reputation, which is a very necessary thing. For that, you had to shine at games, and cricket was the only one for me.

Not that I cared for it above half, at first, but the other great sport was football, and that was downright dangerous; I rubbed along at it only by limping up late to the scrimmages yelping: ‘Play up, you fellows, do! Oh, confound this game leg of mine!’ and by developing a knack of missing my charges against bigger men by a fraction of an inch, plunging on the turf just too late with heroic gasps and roarings.2 Cricket was peace and tranquillity by comparison, without any danger of being hacked in the members – and I turned out to be uncommon good at it.

I say this in all modesty; as you may know, I have three other prime talents, for horses, languages, and fornication, but they’re all God-given, and no credit that I can claim. But I worked to make myself a cricketer, d----d hard I worked, which is probably why, when I look back nowadays on the rewards and trophies of an eventful life – the medals, the knighthood, the accumulated cash, the military glory, the drowsy, satisfied women – all in all, there’s not much I’m prouder of than those five wickets for 12 runs against the flower of England’s batters, or that one glorious over at Lord’s in ’42 when – but I’ll come to that in a moment, for it’s where my present story really begins.

I suppose, if Fuller Pilch had got his bat down just a split second sooner, it would all have turned out different. The Skrang pirates wouldn’t have been burned out of their h--lish nest, the black queen of Madagascar would have had one lover fewer (not that she’d have missed a mere one, I daresay, the insatiable great b---h), the French and British wouldn’t have bombarded Tamitave, and I’d have been spared kidnapping, slavery, blowpipes, and the risk of death and torture in unimaginable places – aye, old Fuller’s got a lot to answer for, God rest him. However, that’s anticipating – I was telling you how I became a fast bowler at Rugby, which is a necessary preliminary.

It was in the ’thirties, you see, that round-arm bowling came into its own, and fellows like Mynn got their hands up shoulder-high. It changed the game like nothing since, for we saw what fast bowling could be – and it was fast – you talk about Spofforth and Brown, but none of them kicked up the dust like those early trimmers. Why, I’ve seen Mynn bowl to five slips and three long-stops, and his deliveries going over ’em all, first bounce right down to Lord’s gate. That’s my ticket, thinks I, and I took up the new slinging style, at first because it was capital fun to buzz the ball round the ears of rabbits and funks who couldn’t hit back, but I soon found this didn’t answer against serious batters, who pulled and drove me all over the place. So I mended my ways until I could whip my fastest ball onto a crown piece, four times out of five, and as I grew tall I became faster still, and was in a fair way to being Cock of Big Side – until that memorable afternoon when the puritan prig Arnold took exception to my being carried home sodden drunk, and turfed me out of the school. Two weeks before the Marylebone match, if you please – well, they lost it without me, which shows that while piety and sobriety may ensure you eternal life, they ain’t enough to beat the MCC.

However, that was an end to my cricket for a few summers, for I was packed off to the Army and Afghanistan, where I shuddered my way through the Kabul retreat, winning undeserved but undying fame in the siege of Jallalabad. All of which I’ve related elsewhere;fn1 sufficient to say that I bilked, funked, ran for dear life and screamed for mercy as occasion demanded, all through that ghastly campaign, and came out with four medals, the thanks of Parliament, an audience of our Queen, and a handshake from the Duke of Wellington. It’s astonishing what you can make out of a bad business if you play your hand right and look noble at the proper time.

Anyway, I came home a popular hero in the late summer of ’42, to a rapturous reception from the public and my beautiful idiot wife Elspeth. Being lionised and fêted, and making up for lost time by whoring and carousing to excess, I didn’t have much time in the first few months for lighter diversions, but it chanced that I was promenading down Regent Street one afternoon, twirling my cane with my hat on three hairs and seeking what I might devour, when I found myself outside ‘The Green Man’. I paused, idly – and that moment’s hesitation launched me on what was perhaps the strangest adventure of my life.

It’s long gone now, but in those days ‘The Green Man’ was a famous haunt of cricketers, and it was the sight of bats and stumps and other paraphernalia of the game in the window that suddenly brought back memories, and awoke a strange hunger – not to play, you understand, but just to smell the atmosphere again, and hear the talk of batters and bowlers, and the jargon and gossip. So I turned in, ordered a plate of tripe and a quart of home-brewed, exchanged a word or two with the jolly pipe-smokers in the tap, and was soon so carried away by the homely fare, the cheery talk and laughter, and the clean hearty air of the place, that I found myself wishing I’d gone on to the Haymarket and got myself a dish of hot spiced trollop instead. Still, there was time before supper, and I was just calling the waiter to settle up when I noticed a fellow staring at me across the room. He met my eye, shoved his chair back, and came over.

‘I say,’ says he, ‘aren’t you Flashman?’ He said it almost warily, as though he didn’t wish quite to believe it. I was used to this sort of thing by now, and having fellows fawn and admire the hero of Jallalabad, but this chap didn’t look like a toad-eater. He was as tall as I was, brown-faced and square-chinned, with a keen look about him, as though he couldn’t wait to have a cold tub and a ten-mile walk. A Christian, I shouldn’t wonder, and no smoking the day before a match.

So I said, fairly cool, that I was Flashman, and what was it to him.

‘You haven’t changed,’ says he, grinning. ‘You won’t remember me, though, do you?’

‘Any good reason why I should try?’ says I. ‘Here, waiter!’

‘No, thank’ee,’ says this fellow. ‘I’ve had my pint for the day. Never take more during the season.’ And he sat himself down, cool as be-d----d, at my table.

‘Well, I’m relieved to hear it,’ says I, rising. ‘You’ll forgive me, but—’

‘Hold on,’ says he, laughing. ‘I’m Brown. Tom Brown – of Rugby. Don’t say you’ve forgotten!’

Well, in fact, I had. Nowadays his name is emblazoned on my memory, and has been ever since Hughes published his infernal book in the ’fifties, but that was still in the future, and for the life of me I couldn’t place him. Didn’t want to, either; he had that manly, open-air reek about him that I can’t stomach, what with his tweed jacket (I’ll bet he’d rubbed down his horse with it) and sporting cap; not my style at all.

‘You roasted me over the common-room fire once,’ says he, amiably, and then I knew him fast enough, and measured the distance to the door. That’s the trouble with these snivelling little sneaks one knocks about at school; they grow up into hulking louts who box, and are always in prime trim. Fortunately this one appeared to be Christian as well as muscular, having swallowed Arnold’s lunatic doctrine of love-thine-enemy, for as I hastily muttered that I hoped it hadn’t done him any lasting injury, he laughed heartily and clapped me on the shoulder.

‘Why, that’s ancient history,’ cries he. ‘Boys will be boys, what? Besides, d’ye know – I feel almost that I owe you an apology. Yes,’ and he scratched his head and looked sheepish. ‘Tell the truth,’ went on this amazing oaf, ‘when we were youngsters I didn’t care for you above half, Flashman. Well, you treated us fags pretty raw, you know – of course, I guess it was just thoughtlessness, but, well, we thought you no end of a cad, and – and … a coward, too.’ He stirred uncomfortably, and I wondered was he going to fart. ‘Well, you caught us out there, didn’t you?’ says he, meeting my eye again. ‘I mean, all this business in Afghanistan … the way you defended the old flag … that sort of thing. By George,’ and he absolutely had tears in his eyes, ‘it was the most splendid thing … and to think that you … well, I never heard of anything so heroic in my life, and I just wanted to apologize, old fellow, for thinking ill of you – ’cos I’ll own that I did, once – and ask to shake your hand, if you’ll let me.’

He sat there, with his great paw stuck out, looking misty and noble, virtue just oozing out of him, while I marvelled. The strange thing is, his precious pal Scud East, whom I’d hammered just as generously at school, said almost the same thing to me years later, when we met as prisoners in Russia – confessed how he’d loathed me, but how my heroic conduct had wiped away all old scores, and so forth. I wonder still if they believed that it did, or if they were being hypocrites for form’s sake, or if they truly felt guilty for once having harboured evil thoughts of me? D----d if I know; the Victorian conscience is beyond me, thank G-d. I know that if anyone who’d done me a bad turn later turned out to be the Archangel Gabriel, I’d still hate the b----d; but then, I’m a scoundrel, you see, with no proper feelings. However, I was so relieved to find that this stalwart lout was prepared to let bygones be bygones that I turned on all my Flashy charms, pumped his fin heartily, and insisted that he break his rule for once, and have a glass with me.

‘Well, I will, thank’ee,’ says he, and when the beer had come and we’d drunk to dear old Rugby (sincerely, no doubt, on his part) he puts down his mug and says:

‘There’s another thing – matter of fact it was the first thought that popped into my head when I saw you just now – I don’t know how you’d feel about it, though – I mean, perhaps your wounds ain’t better yet?’

He hesitated. ‘Fire away,’ says I, thinking perhaps he wanted to introduce me to his sister.

‘Well, you won’t have heard, but my last half at school, when I was captain, we had no end of a match against the Marylebone men – lost on first innings, but only nine runs in it, and we’d have beat ’em, given one more over. Anyway, old Aislabie – you remember him? – was so taken with our play that he has asked me if I’d like to get up a side, Rugby past and present, for a match against Kent. Well, I’ve got some useful hands – you know young Brooke, and Raggles – and I remembered you were a famous bowler, so … What d’ye say to turning out for us – if you’re fit, of course?’

It took me clean aback, and my tongue being what it is, I found myself saying: ‘Why, d’you think you’ll draw a bigger gate with the hero of Afghanistan playing?’

‘Eh? Good lord, no!’ He coloured and then laughed. ‘What a cynic you are, Flashy! D’ye know,’ says he, looking knowing, ‘I’m beginning to understand you, I think. Even at school, you always said the smart, cutting things that got under people’s skins – almost as though you were going out of your way to have ’em think ill of you. It’s a contrary thing – all at odds with the truth, isn’t it? Oh, aye,’ says he, smiling owlishly, ‘Afghanistan proved that, all right. The German doctors are doing a lot of work on it – the perversity of human nature, excellence bent on destroying itself, the heroic soul fearing its own fall from grace, and trying to anticipate it. Interesting.’ He shook his fat head solemnly. ‘I’m thinking of reading philosophy at Oxford this term, you know. However, I mustn’t prose. What about it, old fellow?’ And d--n his impudence, he slapped me on the knee. ‘Will you bowl your expresses for us – at Lord’s?’

I’d been about to tell him to take his offer along with his rotten foreign sermonising and drop ’em both in the Serpentine, but that last word stopped me. Lord’s – I’d never played there, but what cricketer who ever breathed wouldn’t jump at the chance? You may think it small enough beer compared with the games I’d been playing lately, but I’ll confess it made my heart leap. I was still young and impressionable then and I almost knocked his hand off, accepting. He gave me another of his thunderous shoulder-claps (they pawed each other something d--nable, those hearty young champions of my youth) and said, capital, it was settled then.

‘You’ll want to get in some practice, no doubt,’ says he, and promptly delivered a lecture about how he kept himself in condition, with runs and exercises and forgoing tuck, just as he had at school. From that he harked back to the dear old days, and how he’d gone for a weep and a pray at Arnold’s tomb the previous month (our revered mentor having kicked the bucket earlier in the year, and not before time, in my opinion). Excited as I was at the prospect of the Lord’s game, I’d had about my bellyful of Master Pious Brown by the time he was done, and as we took our leave of each other in Regent Street, I couldn’t resist the temptation to puncture his confounded smugness.

‘Can’t say how glad I am to have seen you again, old lad,’ says he, as we shook hands. ‘Delighted to know you’ll turn out for us, of course, but, you know, the best thing of all has been – meeting the new Flashman, if you know what I mean. It’s odd,’ and he fixed his thumbs in his belt and squinted wisely at me, like an owl in labour, ‘but it reminds me of what the Doctor used to say at confirmation class – about man being born again – only it’s happened to you – for me, if you understand me. At all events, I’m a better man now, I feel, than I was an hour ago. God bless you, old chap,’ says he, as I disengaged my hand before he could drag me to my knees for a quick prayer and a chorus of ‘Let us with a gladsome mind’. He asked which way I was bound.

‘Oh, down towards Haymarket,’ says I. ‘Get some exercise, I think.’

‘Capital,’ says he. ‘Nothing like a good walk.’

‘Well … I was thinking more of riding, don’t you know.’

‘In Haymarket?’ He frowned. ‘No stables thereaway, surely?’

‘Best in town,’ says I. ‘A few English mounts, but mostly French fillies. Riding silks black and scarlet, splendid exercise, but d----d exhausting. Care to try it?’

For a moment he was all at a loss, and then as understanding dawned he went scarlet and white by turns, until I thought he would faint. ‘My G-d,’ he whispered hoarsely. I tapped him on the weskit with my cane, all confidential.

‘You remember Stumps Harrowell, the shoemaker, at Rugby, and what enormous calves he had?’ I winked while he gaped at me. ‘Well, there’s a German wench down there whose poonts are even bigger. Just about your weight; do you a power of good.’

He made gargling noises while I watched him with huge enjoyment.

‘So much for the new Flashman, eh?’ says I. ‘Wish you hadn’t invited me to play with your pure-minded little friends? Well, it’s too late, young Tom; you’ve shaken hands on it, haven’t you?’

He pulled himself together and took a breath. ‘You may play if you wish,’ says he. ‘More fool I for asking you – but if you were the man I had hoped you were, you would—’

‘Cry off gracefully – and save you from the pollution of my company? No, no, my boy – I’ll be there, and just as fit as you are. But I’ll wager I enjoy my training more.’

‘Flashman,’ cries he, as I turned away, ‘don’t go to – to that place, I beseech you. It ain’t worthy—’

‘How would you know?’ says I. ‘See you at Lord’s.’ And I left him full of Christian anguish at the sight of the hardened sinner going down to the Pit. The best of it was, he was probably as full of holy torment at the thought of my foul fornications as he would have been if he’d galloped that German tart himself; that’s unselfishness for you. But she’d have been wasted on him, anyway.

However, just because I’d punctured holy Tom’s daydreams, don’t imagine that I took my training lightly. Even while the German wench was recovering her breath afterwards and ringing for refreshments, I was limbering up on the rug, trying out my old round-arm swing; I even got some of her sisters in to throw oranges to me for catching practice, and you never saw anything jollier than those painted dollymops scampering about in their corsets, shying fruit. We made such a row that the other customers put their heads out, and it turned into an impromptu innings on the landing, whores versus patrons (I must set down the rules for brothel cricket some day, if I can recall them; cover point took on a meaning that you won’t find in ‘Wisden’, I know). The whole thing got out of hand, of course, with furniture smashed and the sluts shrieking and weeping, and the madame’s bullies put me out for upsetting her disorderly house, which seemed a trifle hard.

Next day, though, I got down to it in earnest, with a ball in the garden. To my delight none of my old skill seemed to have deserted me, the thigh which I’d broken in Afghanistan never even twinged, and I crowned my practice by smashing the morning-room window while my father-in-law was finishing his breakfast; he’d been reading about the Rebecca Riots3 over his porridge, it seemed, and since he’d spent his miserable life squeezing and sweating his millworkers, and had a fearful guilty conscience according, his first reaction to the shattering glass was that the starving mob had risen at last and were coming to give him his just deserts.

‘Ye d----d Goth!’ he spluttered, fishing the fragments out of his whiskers. ‘Ye don’t care who ye maim or murder; I micht ha’e been killed! Have ye nae work tae go tae?’ And he whined on about ill-conditioned loafers who squandered their time and his money in selfish pleasure, while I nuzzled Elspeth good morning over her coffee service, marvelling as I regarded her golden-haired radiance and peach-soft skin that I had wasted strength on that suety frau the evening before, when this had been waiting between the covers at home.

‘A fine family ye married intae,’ says her charming sire. ‘The son stramashin’ aboot destroyin’ property while the feyther’s lyin’ abovestairs stupefied wi’ drink. Is there nae mair toast?’

‘Well, it’s our property and our drink,’ says I, helping myself to kidneys. ‘Our toast, too, if it comes to that.’

‘Aye, is’t, though, my buckie?’ says he, looking more like a spiteful goblin than ever. ‘And who peys for’t? No’ you an’ yer wastrel parent. Aye, an’ ye can keep yer sullen sniffs to yersel’, my lassie,’ he went on to Elspeth. ‘We’ll hae things aboveboard, plump an’ plain. It’s John Morrison foots the bills, wi’ good Scots siller, hard-earned, for this fine husband o’ yours an’ the upkeep o’ his hoose an’ family; jist mind that.’ He crumpled up his paper, which was sodden with spilled coffee. ‘Tach! There my breakfast sp’iled for me. “Our property” an’ “our drink”, ye say? Grand airs and patched breeks!’ And out he strode, to return in a moment, snarling. ‘And since you’re meant tae be managin’ this establishment, my girl, ye’ll see tae it that we hae marmalade after this, and no’ this d----d French jam! Con-fee – toor! Huh! Sticky rubbish!’ And he slammed the door behind him.

‘Oh, dear,’ sighs Elspeth. ‘Papa is in his black mood. What a shame you broke the window, dearest.’

‘Papa is a confounded blot,’ says I, wolfing kidneys. ‘But now that we’re rid of him, give us a kiss.’

You’ll understand that we were an unusual menage. I had married Elspeth perforce, two years before when I had the ill-fortune to be stationed in Scotland, and had been detected tupping her in the bushes – it had been the altar or pistols for two with her fire-eating uncle. Then, when my drunken guv’nor had gone smash over railway shares, old Morrison had found himself saddled with the upkeep of the Flashman establishment, which he’d had to assume for his daughter’s sake.

A pretty state, you’ll allow, for the little miser wouldn’t give me or the guv’nor a penny direct, but doled it out to Elspeth, on whom I had to rely for spending money. Not that she wasn’t generous, for in addition to being a stunning beauty she was also as brainless as a feather mop, and doted on me – or at least, she seemed to, but I was beginning to have my doubts. She had a hearty appetite for the two-backed game, and the suspicion was growing on me that in my absence she’d been rolling the linen with any chap who’d come handy, and was still spreading her favours now that I was home. As I say, I couldn’t be sure – for that matter, I’m still not, sixty years later. The trouble was and is, I dearly loved her in my way, and not only lustfully – although she was all you could wish as a night-cap – and however much I might stallion about the town and elsewhere, there was never another woman that I cared for besides her. Not even Lola Montez, or Lakshmibai, or Lily Langtry, or Ko Dali’s daughter, or Duchess Irma, or Takes-Away-Clouds-Woman, or Valentina, or … or, oh, take your choice, there wasn’t one to come up to Elspeth.

For one thing, she was the happiest creature in the world, and pitifully easy to please; she revelled in the London life, which was a rare change from the cemetery she’d been brought up in – Paisley, they call it – and with her looks, my new-won laurels, and (best of all) her father’s shekels, we were well-received everywhere, her ‘trade’ origins being conveniently forgotten. (There’s no such thing as an unfashionable hero or an unsuitable heiress.) This was just nuts to Elspeth, for she was an unconscionable little snob, and when I told her I was to play at Lord’s, before the smartest of the sporting set, she went into raptures – here was a fresh excuse for new hats and dresses, and preening herself before the society rabble, she thought. Being Scotch, and knowing nothing, she supposed cricket was a gentleman’s game, you see; sure enough, a certain level of the polite world followed it, but they weren’t precisely the high cream, in those days – country barons, racing knights, well-to-do gentry, maybe a mad bishop or two, but pretty rustic. It wasn’t quite as respectable as it is now.

One reason for this was that it was still a betting game, and the stakes could run pretty high – I’ve known £50,000 riding on a single innings, with wild side-bets of anything from a guinea to a thou. on how many wickets Marsden would take, or how many catches would fall to the slips, or whether Pilch would reach fifty (which he probably would). With so much cash about, you may believe that some of the underhand work that went on would have made a Hays City stud school look like old maid’s loo – matches were sold and thrown, players were bribed and threatened, wickets were doctored (I’ve known the whole eleven of a respected county side to sneak out en masse and p--s on the wicket in the dark, so that their twisters could get a grip next morning; I caught a nasty cold myself). Of course, corruption wasn’t general, or even common, but it happened in those good old sporting days – and whatever the purists may say, there was a life and stingo about cricket then that you don’t get now.