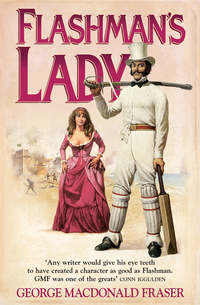

Flashman’s Lady

So the match was made, and Elspeth had the grace not to say she hoped I would lose; indeed, she confided later that she thought Don Solomon had been just a little sharp, and not quite refined in taking her for granted.

‘For you know, Harry, I would never accompany him with Papa against your wishes. But if you choose to accept his wager, that is different – and, oh! it would be such fun to see India and … all those splendid places! But of course, you must play your best, and not lose on my account—’

‘Don’t worry, old girl,’ says I, climbing aboard her, ‘I shan’t.’

That was before dinner. By bed-time I wasn’t so sure.

I was taking a turn about the grounds while the others were at their port, and had just strolled abreast the gates, when someone goes ‘Psst!’ from the shadows, and to my astonishment I saw two or three dark figures lurking in the roadway. One of them advanced, and I choked on my cheroot when I recognised the portly frame of Daedalus Tighe, Heskwire.

‘What the d---l are you doing here?’ I demanded. I’d seen the brute at one or two of the games, but naturally had avoided him. He touched his hat, glanced about in the dusk, and asked for a word with me, if he might make so bold. I told him to go to blazes.

‘Oh, never that, sir!’ says he. ‘You couldn’t vish that, now – not you. Don’t go, Mr Flashman; I promise not to detain you – vhy, the ladies an’ gents will be waitin’ in the drorin’-room, I daresay, and you’ll want to get back. But I hear as ’ow you’re playin’ a single-wicket match tomorrow, ’gainst that fine sportsman Mr Solomon Haslam – werry esteemed cove ’e is, quite the slap-up—’

‘What d’ye know about his cricket?’ says I, and Mr Tighe chuckled beerily.

‘Well, sir, they do say ’e plays a bit – but, lor’ bless yer, ’e’ll be a babby against the likes o’ you. Vhy, in the town I could get fifty to one against ’im, an’ no takers; mebbe even a hundred—’

‘I’m obliged to you,’ says I and was turning away when he said:

‘Mind you, sir, there might be some as would put money on ’im, just on the chance that ’e’d win – vhich is himpossible, o’ course, ’gainst a crack player like you. Then again, even cracks lose sometimes – an’ if you lost, vhy, anyone who’d put a thousand on Haslam – vell spread about, o’ course – vhy, he’d pick up fifty thousand, wouldn’t ’e? I think,’ he added, ‘me calkerlation is about right.’

I nearly swallowed my cheroot. The blind, blazing impudence of it was staggering – for there wasn’t the slightest doubt what the scoundrel was proposing. (And without even a word of what cut he was prepared to offer, rot his insolence.) I hadn’t been so insulted all day, and I d----d his eyes in my indignation.

‘I shouldn’t raise your voice, sir,’ says he. ‘You wouldn’t want to be over’eard talkin’ to the likes o’ me, I’m sure. Or to ’ave folks know that you’ve ’ad some o’ my rhino, in the past, for services rendered—’

‘You infernal liar!’ cries I. ‘I’ve never seen a penny of your d----d money!’

‘Vell, think o’ that, now,’ says he. ‘D’you suppose that Wincent ’as been pocketin’ it again? I don’t see ’ow ’e could ha’ done, neither – seein’ as my letters to you vas writ an’ sealed, vith cash henclosed, in the presence of two reliable legal friends o’ mine, who’d swear that same vos delivered to your direction. An’ you never got ’em, you say? Vell, that Wincent must be sharper than I thought; I’ll just ’ave to break ’is b----y legs to learn ’im better. Still, that’s by the by; the point is’ – and he poked me in the ribs – ‘if my legal friends vos to svear to vot they know – there’s some as might believe you’d been takin’ cash from a bookie – oh, to win, granted, but it’d make a nasty scandal. Werry nasty it would be.’

‘D--n you!’ I was nearly choking with rage. ‘If you think you can scare me—’

He raised his hands in mock horror. ‘I’d never think any such thing, Mr Flashman! I know you’re brave as a lion, sir – vhy, you ain’t even afraid to walk the streets o’ London alone at nights – some rare strange places you gets to, I b’lieve. Places vhere young chaps ’as come adrift afore now – set on by footpads an’ beat almost to death. Vhy, a young friend o’ mine – veil, ’e vosn’t much of a friend, ’cos ’e velched on me, ’e did. Crippled for life, sir, I regret to say. Never did catch the willains that done it, neither. Course, the peelers is shockin’ lax these days—’

‘You villain! Why, I’ve a mind to—’

‘No, you ’aven’t, Mr Flashman. Werry inadwisable it vould be for you to do anythin’ rash, sir. An’ vhere’s the necessity, arter all?’ I could imagine the greasy smile, but all I could see was shadow. ‘Mr Haslam just ’as to vin termorror – an’ I’ll see you’re five thahsand richer straight avay, my dear sir. My legal friends’ll forget … vot they know … an’ I daresay no footpads nor garrotters von’t never come your vay, neither.’ He paused, and then touched his hat again. ‘Now, sir, I shan’t detain you no more – your ladies vill be gettin’ impatient. A werry good night to you – an’ I’m mortal sorry you ain’t goin’ to vin in the mornin’. But think of ’ow cock-a-hoop Mr Haslam’ll be, eh? It’ll be such a hunexpected surprise for ’im.’

And with that he faded into the darkness; I heard his beery chuckle as he and his bullies went down the road.

When I’d got over my indignation, my first thought was that Haslam was behind this, but saner judgement told me he wouldn’t be such a fool – only young idiots like me got hooked by the likes of Daedalus Tighe. G-d, what a purblind ass I’d been, ever to touch his dirty money. He could make a scandal, not a doubt of that – and I didn’t question either that he was capable of setting his roughs on to waylay me some dark night. What the d---l was I to do? If I didn’t let Haslam win – no, by G-d, I was shot if I would! Let him go fornicating round the world with Elspeth while I rotted in my tin belly at St James’s? Not likely. But if I beat him, Tighe would split, for certain, and his thugs would pulp me in some alley one fine night …

You can understand that I didn’t go to bed in any good temper, and I didn’t sleep much, either.

It never rains but it pours, though. I was still wrestling with my dilemma next morning when I received another blow, this time through the smirking agency of Miss Judy, the guv’nor’s trull. I had been out on the gravel watching Solomon’s gardeners roll the wicket on the main lawn for our match, smoking furiously and drumming my fingers, and then took a restless turn round the house; Judy was sitting in one of the arbours, reading a journal. She didn’t so much as glance up as I walked by, ignoring her, and then her voice sounded coolly behind me:

‘Looking for Mrs Leo Lade?’

That was a nasty start, to begin with. I stopped, and turned to look at her. She leafed over a page and went on: ‘I shouldn’t, if I were you. She isn’t receiving this morning, I fancy.’

‘What the d---l have I to do with her?’ says I.

‘That’s what the Duke is asking, I daresay,’ says Miss Judy, giving the journal her sly smile. ‘He has not directed his inquiries to you as yet? Well, well, all in good time, no doubt.’ And she went on reading cool as be-d----d, while my heart went like a hammer.

‘What the h--l are you driving at?’ says I, and when she didn’t answer I lost my temper and knocked the paper from her hand.

‘Ah, that’s my little man!’ says she, and now she was looking at me, sneering in scornful pleasure. ‘Are you going to strike me, as well? You’d best not – there are people within call, and it would never do for them to see the hero of Kabul assaulting a lady, would it?’

‘Not “lady”!’ says I. ‘Slut’s the word.’

‘It’s what the Duke called Mrs Lade, they tell me,’ says she, and rose gracefully to her feet, picking up her parasol and spreading it. ‘You mean you haven’t heard? You will, though, soon enough.’

‘I’ll hear it now!’ says I, and gripped her arm. ‘By G-d, if you or anyone else is spreading slanders about me, you’ll answer for it! I’ve nothing to do with Mrs Lade or the Duke, d’you hear?’

‘No?’ She looked me up and down with her crooked smile and suddenly jerked her arm free. ‘Then Mrs Lade must be a liar – which I daresay she is.’

‘What d’you mean? You’ll tell me, this instant, or—’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t deny myself the pleasure,’ says she. ‘I like to see you wriggle and mouth first, though. Well, then – a little bird from the Duke’s hotel tells me that he and Mrs Lade quarrelled violently last night, as I believe they frequently do – his gout, you know. There were raised voices – his, at first, and then hers, and all manner of names called – you know how these things develop, I’m sure. Just a little domestic scene, but I’m afraid Mrs Lade is a stupid woman, because when the talk touched on his grace’s … capabilities – how it did, I can’t imagine – she was ill-advised enough to mention your name, and make unflattering comparisons.’ Miss Judy smiled sweetly, and patted her auburn curls affectedly. ‘She must be singularly easy to please, I think. Not to say foolish, to taunt her admirer so. In any event, his grace was so tender as to be jealous—’

‘It’s a d----d lie! I’ve never been near the b---h!’

‘Ah, well, no doubt she is confusing you with someone else. It is probably difficult for her to keep tally. However, I daresay his grace believed her; jealous lovers usually think the worst. Of course, we must hope he will forgive her, but his forgiveness won’t include you, I’ll be bound, and—’

‘Shut your lying mouth!’ cries I. ‘It’s all false – if that slattern has been lying about me, or if you are making up this malicious gossip to discredit me, by G-d I’ll make you both wish you’d never been born—’

‘Again, you’re quoting the Duke. A hot-tempered old gentleman, it seems. He spoke – at the top of his voice, according to a guest at the hotel – of setting a prizefighter on to you. It seems he is the backer of some persons called Caunt and the Great Gun – but I don’t know about such things …’

‘Has Elspeth heard this foul slander?’ I shouted.

‘If I thought she would believe it, I would tell her myself,’ says the malicious tart. ‘The sooner she knows what a hound she has married, the better. But she’s stupid enough to worship you – most of the time. Whether she’ll still find you so attractive when the Duke’s pugilists have done with you is another matter.’ She sighed contentedly and turned away up the path. ‘Dear me, you’re shaking, Harry – and you will need a steady hand, you know, for your match with Don Solomon. Everyone is so looking forward to it …’

She left me in a fine state of rage and apprehension, as you can imagine. It almost passed belief that the idiot heifer Lade had boasted to her protector of her bout with me, but some women are stupid enough for anything, especially when tempers are flying – and now that doddering, vindictive old pander of a Duke would sick his bullies onto me11 – on top of Tighe’s threats of the previous evening it was the wrong side of enough. Couldn’t the selfish old lecher realise that his flashtail needed a young mount from time to time, to keep her in running condition? But here I was, under clouds from all directions, still undecided what I should do in my match with Solomon – and at that moment Mynn hove up to bear me away to the pitch for the great encounter. I wasn’t feeling like cricket one little bit.

Our party, and a fair number of local quality riff-raff, were already arranging themselves on chairs and couches set on the gravel before the house – the Duke and Mrs Lade weren’t there, thank G-d: probably still flinging furniture at each other in the hotel – but Elspeth was the centre of attraction, with Judy at her side looking as though she’d just swallowed the last of the cream. Tattling trollop – I gritted my teeth and vowed I’d be even with her yet.

On the other sides of the lawn was the popular mob, for Solomon had thrown open his grounds for the occasion, and had set up a marquee where free beer and refreshments were being doled out to the thirsty; well, if the d----d show-off wanted to let ’em see him being thoroughly beat, that was his business. Oh, Ch---t, though – was I going to beat him? And to compound my confusion, what should I see among a group of flash coves under the trees but the scarlet weskit and face of Daedalus Tighe, Heskwire, come to oversee his great coup, no doubt; he had some likely-looking hard-cases with him, too, all punishing the ale and chortling.

‘Breakfast disagree with you, Flashy?’ says Mynn. ‘You look a mite peaky – hollo, though, there’s your opponent all ready. Come along.’

Solomon was already on the lawn, very business-like in corduroys and pumps, with a straw hat on his black head, smiling at me and shaking hands while the swells clapped politely and the popular crowd shouted and rattled their pots. I stripped off my coat and donned my pumps, and then little Felix spun the bat; I called ‘blade’, and so it was. ‘Very good,’ says I to Solomon, ‘you’ll bat first.’

‘Capital!’ cries he, with a flash of teeth. ‘Then may the better man win!’

‘He will,’ says I, and called for the ball, while Solomon, rot his impudence, went across to Elspeth and made great play of having her wish him luck; he even had the gall to ask her for her handkerchief to tie in his belt – ‘for I must carry the lady’s colours, you know,’ cries he, making a great joke of it.

Of course she obliged him, and then, catching my glare, fluttered that of course I must carry her colours, too, to show no favouritism. But she hadn’t another wipe, so the minx Judy said she must borrow hers to give me – and I finished up with that sly slut’s snot-rag in my belt, and she sitting with her acid tongue in her cheek.

We went out to the wicket together, and Felix gave Solomon guard; he took his time over it, too, patting his blockhole and feeling the pitch before him, very business-like, while I fretted and swung my arm. It was spongy turf, I realised, so I wasn’t going to get much play out of it – no doubt Solomon had taken that into account, too. Much good might it do him.

‘Play!’ calls Felix, and a hush fell round the lawn, everyone expectant for the first ball. I tightened my belt, while Solomon waited in his turn, and then let him have one of my hardest – I’ll swear he went pale as it shot past his shins and went first bounce into the bushes. The mob cheered, and I turned and bowled again.

He wasn’t a bad batter. He blocked my next ball with his hanging guard, played the third straight back to me, and then got a great cheer when he ran two off the fourth. Hollo, thinks I, what have we here? I gave him a slower ball, and he pulled it into the trees, so that I had to plough through the chattering mob to reach it, while he ran five; I was panting and furious when I got back to the crease, but I held myself in and gave him a snorter, dead straight; he went back, and pushed it to his off-side for a single. The crowd yelled with delight, and I ground my teeth.

I was beginning to realise what a desperate business single-wicket can be when you haven’t got fieldsmen, and have to chase every run yourself. You’re tuckered in no time, and for a fast bowler that won’t do. Worse still, no fieldsmen meant no catches behind the stumps, which is how fast men like me get half their wickets. I had to bowl or catch him out myself, and what with the plump turf and his solid poking away, it looked like being the deuce of a job. I took a slow turn, recovering my breath, and then bowled him four of my fastest; the first shaved his stumps, but he met the other three like a game-cock, full on the blade, and they brought him another five runs. The crowd applauded like anything, and he smiled and tipped his hat. Very good, thinks I, we’ll have to see to this in short order.

I bowled him another score or so of balls – and he took another eight runs, carefully – before I got what I wanted, which was a push shot up the wicket, slightly to my left. I slipped deliberately as I went to gather it, and let it run by, at which Solomon, who had been poised and waiting, came galloping out to steal a run. Got you, you b----rd, thinks I, and as I scrambled up, out of his path, pursuing the ball, I got him the deuce of a crack on the knee with my heel, accidental-like. I heard him yelp, but by then I was lunging after the ball, scooping it up and throwing down the wicket, and then looking round all eager, as though to see where he was. Well, I knew where he was – lying two yards out of his ground on his big backside, holding his knee and cursing.

‘Oh, bad luck, old fellow!’ cries I. ‘What happened? Did you slip?’

‘Aaarr-h!’ says he, and for once he wasn’t smiling. ‘You hacked me on the leg, confound it!’

‘What?’ cries I. ‘Oh, never! Good l--d, did I? Look here, I’m most fearfully sorry. I slipped myself, you know. Oh, my G-d!’ says I, clapping my brow. ‘And I threw down your wicket! If I’d realised – I say, Felix, he don’t have to be out, does he? I mean, it wouldn’t be fair?’

Felix said he was run out, no question; it hadn’t been my fault I’d slipped and had Solomon run into me. I said, no, no, I wouldn’t have it, I couldn’t take advantage, and he must carry on with his innings. Solomon was up by now, rubbing his knee, and saying, no, he was out, it couldn’t be helped; his grin was back now, if a bit lop-sided. So we stood there, arguing like little Christians, myself stricken with remorse, pressing him to bat on, until Felix settled it by saying he was out, and that was that. (About time, too; for a moment I’d thought I was going to convince him.)

So it was my turn to bat, shaking my head and saying what a d----d shame it had been; Solomon said it was his clumsiness, and I mustn’t fret, and the crowd buzzed with admiration at all this sporting spirit. ‘Kick ’im in the crotch next time!’ bawls a voice from the trees, and the quality pretended not to hear. I took guard; twenty-one he’d scored; now we’d see how he bowled.

It was pathetic. As a batter he’d looked sound, if dull, with some good wrist-work, but from the moment I saw him put the ball to his eye and waddle up with that pregnant-duck look of earnestness on his face, I knew he was a duffer with the ball. Quite astonishing, for he was normally a graceful, sure-moving man, and fast for all his bulk, but when he tried to bowl he was like a shire horse on its way to the knackers. He lobbed with the solemn concentration of a dowager at a coconut shy, and I gloated inwardly, watched it drop, drove with confidence – and mishit the first ball straight down his throat for the simplest of catches.

The spectators yelled in amazement, and by George, they weren’t alone. I flung down my bat, cursing; Solomon stared in disbelief, half-delighted, half-frowning. ‘I believe you did that on purpose,’ cries he.

‘Did I—!’ says I, furious. I’d meant to hit him into the next county – but ain’t it the way, if a task is too easy, we botch it often as not? I could have kicked myself for my carelessness – thinking like a cricketer, you understand. For with 21 runs in it, I might easily lose the match now – the question was: did I want to? There was Tighe’s red waistcoat under the trees – on the other hand, there was Elspeth, looking radiant, clapping her gloved hands and crying ‘Well played!’ while Solomon tipped his hat gracefully and I tried to put on a good face. By Jove, though, it was him she was looking at – no doubt picturing herself under a tropic moon already, with inconvenient old Flashy safely left behind – no, by G-d, to the d---l with Tighe, and his threats and blackmail – I was going to win this match, and be d----d to everyone.

We had a sandwich and a glass, while the swells chattered round us, and the Canterbury professional rubbed embrocation on Solomon’s knee. ‘Splendid game, old fellow!’ cries the Don, raising his lemonade in my direction. ‘I’ll have some more of my lobs for you directly!’ I laughed and said I hoped they weren’t such twisters as his first one, for it had had me all at sea, and he absolutely looked pleased, the b----y farmer.

‘It is so exciting!’ cries Elspeth. ‘Oh, who is going to win? I don’t think I could bear it for either of them to lose – could you, Judy?’

‘Indeed not,’ says Judy. ‘Capital fun. Just think, my dear – you cannot lose, either way, for you will gain a jolly voyage if the Don wins, or if Harry succeeds, why, he will have two thousand pounds to spend on you.’

‘Oh I can’t think of it that way!’ cries my darling spouse. ‘It is the game that counts, I’m sure.’ D----d idiot.

‘Now then, gentlemen,’ cries Felix, clapping his hands. ‘We’ve had more eating and drinking than cricket so far. Your hand, Don,’ and he led us out for the second innings.

I had learned my lesson from my first bowling spell, and had a good notion now of where Solomon’s strength and weakness lay. He was quick, and sure-footed, and his back game was excellent, but I’d noticed that he wasn’t too steady with his forward strokes, so I pitched well up to him, on the leg stump; the wicket was getting the green off it, with being played on, and I’d hopes of perhaps putting a rising ball into his groin, or at least making him hop about. He met my attack pretty well, though, and played a hanging guard, taking the occasional single on the on side. But I pegged away, settling him into place, with the ball going into his legs, and then sent one t’other way; he didn’t come within a foot of it, and his off-stump went down flat.

He’d made ten runs that hand, so I had 32 to get to win – and while it ain’t many against a muffin of a bowler, well, you can’t afford a single mistake. And I wasn’t a batter to trade; however, with care I should be good enough to see Master Solomon away – if I wanted to. For as I took guard, I could see Tighe’s red weskit out of the corner of my eye, and felt a tremor of fear up my spine. By George, if I won and sent his stake money down the drain, he’d do his best to ruin me, socially and physically, no error – and what was left the Duke’s bruisers would no doubt share between ’em. Was anyone ever in such a cursed fix – but here was Felix calling ‘Play!’ and the Don shuffling up to deliver his donkey-drop.

It’s a strange thing about bad bowling – it can be deuced difficult to play, especially when you know you have only one life to lose, and have to abandon your usual swiping style. In an ordinary game, I’d have hammered Solomon’s rubbish all over the pasture, but now I had to stay cautiously back, while he dropped his simple lobs on a length – no twist at all but dead straight – and I was so nervous that I edged some of them, and would have been a goner if there’d been even an old woman fielding at slip. It made him look a deal better than he was, and the crowd cheered every ball, seeing the slogger Flashy pinned to his crease.

However, I got over my first shakes, tried a drive or two, and had the satisfaction of seeing him tearing about and sweating while I ran a few singles. That was a thing about single-wicket; even a good drive might not win you much, for to score one run you had to race to the bowler’s end and back, whereas in an ordinary match the same work would have brought you two. And all his careering about the outfield didn’t seem to trouble his bowling, which was as bad – but still as straight – as ever. But I hung on, and got to a dozen, and when he sent me a full pitch, I let fly and hit him clean over the house, running eight while he vanished frantically round the building, with the small boys whooping in his wake, and the ladies standing up and squeaking with excitement. I was haring away between the wickets, with the mob chanting each run, and was beginning to think I’d run past his total when he hove in sight again, trailing dung and nettles, and threw the ball across the crease, so that I had to leave off.

So there I was, with 20 runs, 12 still needed to win, and both of us blowing like whales. And now my great decision could be postponed no longer – was I going to beat him, and take the consequences from Tighe, or let him win and have a year in which to seduce Elspeth on his confounded boat? The thought of him murmuring greasily beside her at the taffrail while she got drunk on moonlight and flattery fairly maddened me, and I banged his next delivery against the front door for another three runs – and as I waited panting for his next ball, there under the trees was the beast Tighe, hat down on his brows and thumbs hooked in his weskit, staring at me, with his cudgel-coves behind him. I swallowed, missed the next ball, and saw it shave my bails by a whisker.