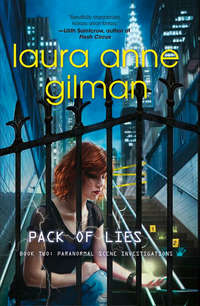

Pack of Lies

Not that anything I picked up was admissible in the court of law, even perfectly preserved, but we didn’t exactly deal with the courts, or law, as most of the world knew it. We were of the Cosa, for the Cosa, and the Cosa determined what—if any—punishment would be handed out, based on what we reported. That was why the “Unaffiliated” part of “Private Unaffiliated Paranormal Investigations” was so important. The Cosa entire wasn’t exactly filled with love and trust: Council looked down at lonejacks, lonejacks sneered at Council, and the fatae thought most humans were jumped-up Johnny-come-latelies, Talent only a little bit better. And what most Talent thought of the fatae could be summed up in two words: treacherous bastards. Have you read a fairy tale lately? Not the Disney kind; the real stuff. Even the good fairies are not the type you’d invite in for tea.

I no sooner had the thought than I looked up and had my attention caught by a good-looking guy sitting across the train from me, slouched in his seat, leather jacket nicely scruffed and jeans worn white in interesting places. While normally I’m all about the good-looking bad boy—or, occasionally, girl—I shook my head and smiled, to his obvious disappointment. The gills at the side of his neck were a dead giveaway, if you knew what you were looking for. Pickups were all well and fun, but I’d learned my lesson about playmates on office time. Anyway, mer-folk weren’t my thing. Sardine-breath was a total turnoff.

Although it was reassuring to know that some human/fatae relations were still going strong.

The subway dumped me out at my stop, and I emerged into a distractingly normal scene: bright sunshine and busy traffic; people going in and out of the stores and buildings that lined our street. There were only two teenagers lounging on the stoop of the building next to ours—either the usual gang had decided to go to school today, or they’d gotten jobs. I gave the two a distracted wave, but didn’t pause for our usual exchange of friendly catcalls.

I was buzzed into our lobby by the current-lock the Guys had put there to let team members in without needing to worry about a key, and took the stairs slowly, feeling the burn in my legs. We had an elevator, but I didn’t like using it. It wasn’t fear, or guilt, exactly. None of us used it anymore, unless Stosser herded us into it, like he had this morning. There were bad vibes in that shaft. And the exercise was good for me, anyway. Current burned calories, but it didn’t build muscles.

“Anyone home?”

The office was quiet, and the coffeemaker was turned off; two signs that I was the first back. Where the hell was Venec? It was almost lunchtime; maybe he had run out to get a sandwich? If so, I hoped he brought back extras: I suddenly realized that I was starving. There was a bodega on the corner that made a fabulous meatball grinder, if he hadn’t brought in food….

I dumped my coat in the front closet, and ran my fingers through my hair, trying to fluff it up. It was cut short again, curling around my ears, and was my normal wheat-blond color, for now. I had been contemplating going back to bright red, but the almost translucent whiteness of the ki-rin’s mane stuck in my head, and I started to wonder if it was time to bleach it all out again….

“And spend half a year waiting for your hair to recover? Maybe not.” I used to change my hair color the way Nick changed his socks—once every week or so—but bleaching wasn’t one of my favorite pastimes.

Even as I was debating styles with myself, I was moving down the carpeted hallway, the weight of my gleanings a solid, unwelcome presence in my brain. Food, hair, everything my brain was churning over was just a distraction. I didn’t want the gleanings in there any longer … but I wasn’t exactly looking forward to the unloading, either. I loved my job, but I hated this part.

The room next to Ian’s office was the best-warded one; the walls had been painted a soothing shade of off-white, and the pale green carpet everywhere else had been pulled up and bamboo flooring put down. There was a single wooden table and a single wooden chair in the room, and nothing else. I closed the door behind me, and leaned against it, trying to let my center settle itself.

“Seal and protect,” I said, triggering the wards we had set up to keep things inside the room inside the room. Once I felt the wards click into place, I pulled out the chair and sat down at the table.

Wood. Everything in our office was wood or plastic; no metal if it could be avoided. Wood didn’t conduct current the way metal did, which meant we didn’t have to be quite so careful all the damned time. I placed my hands down on the surface, my palms sweaty against the varnish, and exhaled.

“All right,” I said to the packet inside me, reaching down with a gentle mental urge. “Come on out and show me what we’ve got.”

We’d originally tried to create a virtual lockroom for things we pulled from scenes, both magical trace and physical debris. It worked great on the deposit, but got corrupted whenever someone tried to access it. We still hadn’t licked that problem. This dump-and-display was something that Stosser and I had invented out of old spells and new needs. Some of the stuff the team came up with worked, and some didn’t. We had to be flexible, adapt. Find better ways to fail, and then find a way not to fail.

Visuals were the easiest to process and share. Anyone could do it, theoretically. In practice, not so much. Nick and Sharon both made a total hash out of every try on their own, Pietr was around sixty-five percent, and even Nifty only got about eighty percent of each gleaning back in one piece.

I had a consistent ninety-three percent return rate on visuals, and a decent eighty-two percent on the other senses. That was why, no matter what happened in practice, it was me in the barrel, every time, and the hell with everyone taking turns.

Basically, the cantrip used current to create a permanent, three-dimensional display of the visual record I had garnered, sort of like what a computer would generate using pixels, only it was running off the electrical and magical impulses of my brain. The only problem was that, although the image would be here, in the room, I’d still be the one hosting it. The echo would still be in my brain until we dumped the gleaning entirely and I could detox, which generally required a full dose of current, a pitcher of margaritas, and a very hot shower.

I wasn’t all that thrilled with my gray matter being used in that way, but Stosser swore it wasn’t doing any permanent damage, and so far it seemed to be working. Whatever worked, we used.

It wasn’t something I was going to tell my mentor about, though. J had let me hunt for the truth about my dad’s murder when I was a teenager, had seen how much the simple fact of knowing what had happened to Zaki set me free. He was coming to terms with what I did, the physical and magical risks, but that didn’t mean he liked it, and he’d like this bit of current-risk even less. J’s always—some part of him—going to see me as the kid he took under his wing, someone he needs to protect. So, for the first time in my life, I wasn’t telling him everything.

I sat back, relaxed as much as I could, and closed my eyes. The current-camera rolled, the virtual film unreeled, and the figures took form in front of me, one-third of the size but every bit as real. The shiver I’d had at the scene intensified, until it racked my entire body, a seemingly endless rolling wave of cold rippling along my skin. I’d known it was going to happen, it happened every time, even in training, which was why I was doing this alone. Unloading sucked.

The problem was, you couldn’t disengage from what you gleaned, not after you took it inside. Visuals, sound, magical trace, it all carried emotional residue—a thousand tiny fishhooks that caught at you. We’d learned that the hard way, going in to gather trace on murder victims during our first case. Then, we’d gotten caught up in the last moments of the victims’ lives, almost been swamped by the experience. We’d refined the process since then, so it was an external view only that kept the hooks to a minimum. What we missed in information we avoided in agony and near-death. I was all about that.

Freaky shivers, I could live with.

The image flickered with the current I infused into it, and came to life. Girl, check, dressed in cute clubbing clothes totally unsuited for the weather, her coat open to the air. She was bubbly, bouncing. I could almost feel her adrenaline rush in the way she moved. I knew that rush, had been caught up in it myself over the years, when you’re so tired and so energized you don’t think you could sleep even if you were dead. Your brain’s going a hundred miles an hour, and you know you’re not making sense anymore, and you just don’t care, because you feel so damn good.

I forced myself to look away from her. Where was … there was the ki-rin. For something so pale, it blended really well with the predawn shadows. She skipped ahead, and it fell back a couple of paces … and that was when it happened.

I made it about halfway through before I threw up, but my concentration stayed steady on the job, even while I was heaving the remains of coffee and bagels onto the floor.

three

When I unsealed the wards and opened the door, Venec was standing there in the hallway. You know how some guys just make you feel better by looking at them? Not comforting or daddylike, just …”all right, you’re here, the ground is solid” kind of way? Venec was like that. Well, sometimes, anyway. When he wasn’t making you feel like an idiot.

He handed me a mug, and I took it automatically, my hand shaking more than I wanted. Venec took note, his gaze sharp, but he didn’t say anything. Tea, not coffee. Not Pietr’s green tea: herbal. My face screwed up in distaste even as I was drinking it. Heavy on the sugar, and I could feel my energy level starting to pick up again. Burning too many calories, using up too much current. I had to remember to watch that.

“You done in there?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

Venec stood there and watched me drinking, his gaze on my face like a nanny—or a dark-feathered falcon, watching a rabbit to see which way it was going to hop. He didn’t touch me, or try to offer any kind of comfort, which was good, because I didn’t want any. I needed the rawness, the bitter taste in my mouth that not even sweet tea could erase, the acid burning in my gut. I needed to remember every detail of what I had seen, what I had felt. It wasn’t even close to what any of the actual participants had felt, distanced by being third-person, but it would keep me going when we hit dead ends or inconsistent facts, give me the energy to push through and keep working.

The truth was I hadn’t seen much of anything of the attempted assault, just a scuffle in the shadows. The flash of hooves and horn, after, had been far more clear. My brain was filling in more of those shadowed details than was healthy, but I didn’t know how to stop it. Curse of an overactive empathy, one woman to another. If one of the guys on the team had been better at gleaning …

No. My instinctive reaction to that thought was, well, instinctive. As bad as it was that I had eavesdropped like this … even if the girl never knew we were poking around in her trauma, somehow I felt I had a responsibility to her now, to take care of that trauma. I couldn’t protect her, but I could protect her memories.

The fact that I couldn’t, really, that it was evidence now, preserved for anyone on the team to look at … well, they still had to go through me, in order to view it. That was a distinction without a difference but somehow, it helped

It did strike me as worrisome that while the initial attack made me feel ill, the ki-rin’s murder of the assailant didn’t seem to affect me; it was as though I’d been watching a real—nonmagical—movie, like the blood and gore and dying wasn’t real. Maybe because the ki-rin was fatae, I hadn’t picked up its emotions from the gleaning, and I was reacting to that blank space? The dead guy had been a real human being, and he was dead. Why wasn’t I feeling anything?

Because he’d assaulted her. Because I was glad he was dead. The thought bothered me, a lot. Justifiable, yeah, but we were supposed to see the facts, and I couldn’t do that if I let my emotions cloud judgment, maybe make me overlook something. That was as bad as trying to protect the victim, in its own way.

The tea was doing its job, settling my stomach enough that I didn’t feel like I was going to puke again. I finished the rest of the liquid, and held it upside down to show the boss I’d been a good little girl.

Venec looked like he was going to say something else, then stopped and tilted his head, looking at me like I was some new bit of evidence. That feeling that tiptoed into me whenever he did that came back, little muddy cat feet.

“What?” I heard the defensiveness in my voice, and reached down to touch my core, almost in reflex. But no, the current there was still and calm. Damn it, I would not let him get to me, not just by looking at me with that heavy gaze, like I was being weighed and judged, and the jury was still out. Nobody, not even J, not even my dad, had ever made me feel like that. I didn’t like it, at all.

“Trigger the display for me, please,” Venec said, and I got the feeling that wasn’t what he had meant to say, but I was still unnerved enough that I didn’t push. He could trigger it himself, with a little effort, and I was almost tempted to tell him to do so, but my mentor had taught me manners, and I had some natural smarts to go with it. The office mood was informal, but I never made the mistake of thinking that orders weren’t meant to be obeyed, even if they weren’t phrased as orders.

“There’s soup in the ready-room,” the Big Dog went on, still staring at me. “Go eat something before you fall over.”

I stared back at him, not quite sure he was speaking in English. Soup. Soup … sounded okay. My stomach could handle soup.

And it hadn’t been a suggestion. The sugar in the tea had helped, but it was going to drop me into a crash pretty damn soon, if I wasn’t careful.

I went back into the room to reset and trigger the display, then pushed past him and headed for the kitchenette. Venec went into the room and I heard him sigh. Ah, give me a break, I thought; I’d cleaned up the worst of it. It was just going to smell a little musty in there for a while, was all.

The break room was still empty, and I found the soup in the fridge easily enough, tossing it into our small, battered microwave and letting it reheat, scrounging some crackers and a soda while I waited.

It was another half hour before the rest of the team started to straggle back from the scene. Nick was the first through the door. He stopped short when he saw me, and pasted on a snarky grin.

“Hey, Dandelion.”

He loved calling me that, because of my hair being short and fluffy and naturally blond. I let him think it annoyed me, because it amused both of us. The things we did, the way the Guys pushed us, and we pushed ourselves, a lot of stress built up and there was only so much drinking you could do and still do your job. Teasing let us blow off some of that tension in reasonably healthy ways.

I’d been in some situations—high school being the prime example—where the allegedly friendly sniping could get nasty. Not here. Not to say we didn’t occasionally do damage, especially Sharon’s smart, sharp tongue, but it was never intentional.

From the very beginning, it had been like that, all the parts that didn’t seem to fit somehow fitting anyway. Stosser and Venec had handpicked each of us, not just for our individual skills, but how we’d form a team. I don’t know how they did it, but … it worked. God knows there was the normal tension you get when you throw high achievers into close contact, but there was more to it than just being coworkers, from that very first day. We counted on each other to be there—the job required us to work together, or fail.

The closest I could describe it to J had been that we were packmates. You didn’t eat your own.

While all this skittered through my brain, Nick was waiting there, his body language expectant.

I sighed and gave in to ritual. “Bite me, Shune.”

His put-on grin softened to a smile with real humor. “Am I the first one back?”

I was curled up on the couch in the ready-room, which had once been the lobby of the original office. I suppose there might have been better, more private places for us to hang out, but the kitchenette was there, and the comfortable chairs, and somehow we all just naturally gathered there when we were all in the office and not otherwise working. That meant that anyone walking in saw us immediately, but we didn’t get many unannounced visitors. In fact, other than our first client and her son, I don’t think anyone had come to the office except us.

“No,” I said in response. “I was. You’re second. As usual.”

My heart really wasn’t in banter today, though, and I guess he realized that, because he just nodded, letting the conversation die quietly. I spooned up some more of the soup—a decent tomato bisque—and watched him put his coat away.

“You get your shit from the cop?” I asked, I guess as a peace offering.

“Yeah.”

He didn’t sound like his usual puppy-dog enthusiastic self in that, and I sat up and looked more closely at him. Nick was slight, almost scrawny, with perpetually tousled brown hair that always looked like he’d just rolled out of bed, but he’d started out the morning looking if not dapper, then decently put-together. Now, he looked like crap, and his brown eyes had a cast to them that I was starting to get all too familiar with. “What?”

“Nothing. I don’t know.” He shrugged, a gesture that drove me crazy.

“What?” Unlike with Venec, I pushed Nick. Unlike Venec, Nick liked to confide.

“Nothing.” He saw the look I was giving him, and smiled again, this time with the real sweet warmth I was used to seeing from him. “Seriously. I got the guy’s signature, so we can rule him out of the evidence. I’m tired, that’s all.”

Uh-huh. We’d been working together long enough he couldn’t bullshit me quite that easily. Smile or no, he was upset about something.

“Guy was scummy?” You couldn’t always tell from a signature, but … sometimes it just oozed.

“No.” Nick shrugged again, not finding the words he needed. “It’s just … he’s a cop.”

Ah. I understood, the way I wouldn’t have a couple of months ago. You work with crap, no matter how clean you are inside, a stink of it stays with you. It’s like the smell inside the workroom—enough people throw up over time, and the smell won’t ever go away, no matter how much lemon-scented cleanser we used. Cops stank. Even the good ones.

There wasn’t really anything to say. Part of the job. Like carrying around the memory of an assault that didn’t happen to you. I lifted my spoon. “You want some soup?”

Nick made a face, indicating his opinion of soup. “Nah. Nifty said he’d pick up a pizza on his way back.”

I must have gone green or something, because he grabbed the container of soup and had the trash can under my face before I was halfway off the sofa. My boy’s got good ref lexes.

“Sorry, ah, hell, Bonnie, I’m sorry … here.” He put the soup down and grabbed a paper towel from the counter, wetting it under the faucet and handing it to me.

I sat back and wiped my face with the back of my hand, then realized what he’d given me the paper for and wiped my hands with it, instead. So much for that soup.

Nick got me back on the sofa, and dropped himself down next to me.

“You okay? You got a stomach bug?”

Easier to claim that, but … his concern was real, and we were honest with each other. You had to be, if you expected them to have your back. Nobody got to pretend to be a hero. “Scummy,” I said, and tried to smile. He got it. He knew what my job on the scene had been, and what it meant.

He put his arm around my shoulders, his brown eyes puppy-sorrowful. “These things … nobody should have to go through it, and we shouldn’t have to witness it, either.”

I smiled a little and nodded, but there wasn’t any comfort in his words. He didn’t understand. He couldn’t really. Oh, he got it intellectually. Intellectual understanding had shit to do with it.

You talk about rape, and every female over puberty understands, way more than a guy ever could, even the most sympathetic gay-or-straight male. Women know, instinctively; hammered into us by society, every single day of our lives, even before we know what sex really is. Even if you never talked about it, it was there, lurking behind your left shoulder, an awareness of risk, even if nobody ever touches you without your consent.

But that wasn’t what was making me uneasy, why what I’d seen was bothering me so. Not exactly. Violence I could handle. I had never been a sheltered child, and I knew that people weren’t angels—not that the angeli were all that nice, from what I’d heard. It was the entire concept of sex-as-violence that was … More than alien to me, it was supersize noncarbon-based life-form alien. J said I was a hedonist, I just believed that mutual pleasure was a noble goal. To me, sex was play: it was an expression of affection, of mutual satisfaction, and yeah, when time, of procreation. That someone could use it to hurt someone else? Being reminded that, in the wrong minds, it can also be a weapon? Scummy. Scary.

I struggled to hold on to my anger from before. Anger was better than fear. Anger I could use.

Nick rested his head on my shoulder, almost a cuddle, and even though it wasn’t anything he hadn’t done before, on tough days, my body shifted away from his. Then he sighed, and I felt a sudden urge to comfort him overriding my own discomfort. Unlike me, Nick had been sheltered. Dealing with scummy took more out of him than he wanted to admit.

Without thinking about it, my arm lifted, draping itself around his shoulders. Nick and I’d flirted—hell, we still flirted, because that was what we did—but I just didn’t react to him that way, and Nicky’d adapted. Sometimes it was nice to have sex out of the picture and off the table, so you could offer comfort without wondering if anything else was being offered, too.

“Hey, guys. Whoops, did we interrupt something?”

Pietr had come in, unnoticed as usual, followed by Nifty, burdened with two pizza boxes, and Sharon, closing the door behind them. Still no sign of Stosser, unless he’d come in while I was in the workroom and Venec hadn’t thought to mention it?

“Bonnie …”

“Bonnie is just fine,” I interrupted, giving Nick a hard elbow in the ribs, and forcing him to move away a little. I’d let him coddle me, a little bit, because he was Nick and it made him feel better. But be damned if I’d announce it to the entire damned pack. He took the hint, and shut up.

“I put the gleanings on loop in the warded workroom,” I told them, even as they were stuffing their coats in the closet, and heading for the coffee. “Venec’s in there now. No idea where Stosser is—he went to interview the victim.”

There were a few winces at that: I wasn’t the only one assuming the worst. Ian Stosser might be smooth to the outside world, but we knew him a little better than most. Still, when he wanted something he could ooze compassion and caring. Just because he rarely used it on us anymore was no need to assume the worst … right? And he had agreed to be gentle with the girl. He wasn’t going to screw it up.

Nifty put the pizzas down on the counter, and opened the lid of one. The smell filled the air, and while normally the combination of tomato, garlic and oregano would make me a happy girl, at this exact moment I didn’t want to be anywhere near food.

“I’m … going to go get Venec,” I said, uncurling from the sofa and making my escape into the hallway before anyone could say anything. I made a quick pit stop into the bathroom, to splash some water on my face and rinse my mouth out. It was your basic small-office restroom: two stalls, two sinks, wall-size mirror over the sinks, but about a month ago Sharon had made a big deal about putting new bulbs in overhead, so she could, as she said, apply makeup without looking like a corpse, and they cast a gentler, kinder light I suddenly really appreciated.