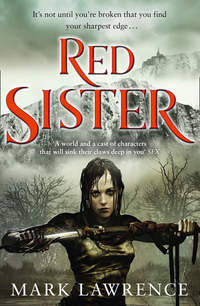

Red Sister

‘Saida’s back in the cells …’ the girl said. ‘They told me I would go first.’

Argus peered at the child. A small thing in shapeless linen – not street rags, covered in rusty stains, but a serf’s wear none the less. She might be nine. Argus had lost the knack for telling. His older two were long grown, and little Sali would always be five. This girl was a fierce creature, a scowl on her thin, dirty face. Eyes black below a short shock of ebony hair.

‘Might have been the other,’ Partnis said. ‘She was the big one.’ He lacked conviction. A fight-master knows the fire when he sees it.

‘Where’s Saida?’ the girl asked.

The abbess’s eyes widened a fraction. It almost looked like hurt. Gone, quicker than the shadow of a bird’s wing. Argus decided he imagined it. The Abbess of Sweet Mercy was called many things, few of them to her face, and ‘soft’ wasn’t one of them.

‘Where’s my friend?’ the girl repeated.

‘Is that why you stayed?’ the abbess asked. She pulled a hoare-apple from her habit, so dark a red it could almost be black, a bitter and woody thing. A mule might eat one – few men would.

‘Stayed?’ Dava asked, though the question hadn’t been pointed her way. ‘She stayed ’cos this is a bloody prison and she’s tied and under guard!’

‘Did you stay to help your friend?’

The girl didn’t answer, only glared up at the woman as if at any moment she might leap upon her.

‘Catch.’ The abbess tossed the apple towards the girl.

Quick as quick a small hand intercepted it. Apple smacking into palm. Behind the girl a length of rope dropped to the ground.

‘Catch.’ The abbess had another apple in hand and threw it, hard.

The girl caught it in her other hand.

‘Catch.’

Quite where the abbess had hidden her fruit supply Argus couldn’t tell, but he stopped caring a heartbeat later, staring at the third apple, trapped between two hands, each full of the previous two.

‘Catch.’ The abbess tossed yet another hoare-apple, but the girl dropped her three and let the fourth sail over her shoulder.

‘Where’s Saida?’

‘You come with me, Nona Grey,’ the abbess said, her expression kindly. ‘We will discuss Saida at the convent.’

‘I’m keeping her.’ Partnis stepped towards the girl. ‘A treasured daughter! Besides, she damn near killed Raymel Tacsis. The family will never let her go free. But if I can show she has value they might let me put her into a few fights first.’

‘Raymel’s dead. I killed him. I—’

‘Treasured? I’m surprised you let her go, Mr Reeve,’ the abbess cut across the girl’s protests.

‘I wouldn’t have if I’d been there!’ Partnis clenched his hand as if trying to recapture the opportunity. ‘I was halfway across the city when I heard. Got back to find the place in chaos … blood everywhere … Tacsis men waiting … If the city guard hadn’t hauled her up here she’d be in Thuran’s private dungeon by now. He’s not a man to lose a son and sit idle.’

‘Which is why you will give her to me.’ The abbess’s smile reminded Argus of his mother’s. The one she’d use when she was right and they both knew it. ‘Your pockets aren’t deep enough to get young Nona out of here should the Tacsis boy die, and if you did obtain her release neither you nor your establishment are sufficiently robust to withstand Thuran Tacsis’s demands for retribution.’

The girl tried to interrupt. ‘How do you know my name? I didn’t—’

‘Whereas I have been friends with Warden James longer than you have been alive, Mr Reeve.’ The abbess cut across the girl again. ‘And no sane man would mount an attack on a convent of the faith.’

‘You shouldn’t take her for a Red Sister.’ Partnis had that sullen tone men get when they know they’ve lost. ‘It’s not right. She’s got no Ancestor faith … and she’s all but a murderer. Vicious, it was, the way they tell it …’

‘Faith I can give her. What she’s got already is what the Red Sisters need.’ The abbess reached out a plump hand towards the girl. ‘Come, Nona.’

Nona glanced up at John Fallon, at Partnis Reeve, at the hangman and the noose swaying beside him. ‘Saida is my friend. If you’ve hurt her I’ll kill you all.’

In silence she walked forward, placing her feet so as not to step on the fallen apples, and took the abbess’s hand.

Argus and the others watched them leave. At the gates, they paused, black against the red sun. The child released the abbess’s hand and took three paces towards the covered mound. Old Herber and his mule stood, watching, as bound by the moment as the rest of them. Nona stopped, staring at the mound. She looked towards the men at the gallows – a long, slow look – then returned to the abbess. Seconds later the pair had vanished around the corner.

‘Marking us for death she was,’ Dava said.

Still joking. Still not funny.

3

A juggler once came to Nona’s village, a place so small it had neither a name nor a market square. The juggler came dressed in mud and faded motley, a lean look about him. He came alone, a young man, dark eyes, quick hands. In a sackcloth bag he carried balls of coloured leather, batons with white and black ribbons, and crudely made knives.

‘Come, watch, the great Amondo will delight and amaze.’ It sounded like a phrase he didn’t own. He introduced himself to the handful of villagers not labouring in field or hut and yet brave enough to face a Corridor wind laced with icy rain. Laying his hat between them, broad-brimmed and yawning for appreciation, he reached for four striped batons and set them dancing in the air.

Amondo stayed three days, though his audience dried up after the first hour of the first evening. The sad fact is that there’s only so much entertainment to be had from one man juggling, however impressive he might be.

Nona stayed by him though, watching every move, each deft tuck and curl and switch. She stayed even after the light failed and the last of the children drifted away. Silent and staring she watched as the juggler started to pack his props into their bag.

‘You’re a quiet one.’ Amondo threw her a wizened apple that sat in his hat along with several better examples, two bread rolls, a piece of Kennal’s hard goat’s cheese, and somewhere amongst them a copper halfpenny clipped back to a quarter.

Nona held the apple close to her ear, listening to the sound of her fingers against its wrinkles. ‘The children don’t like me.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

Amondo waited, juggling invisible balls with his hands.

‘They say I’m evil.’

Amondo dropped an invisible ball. He left the others to fall and raised a brow.

‘Mother says they say it because my hair is so black and my skin is so pale. She says I get my skin from her and my hair from my da.’ The other children had the tan skin and sandy hair of their parents, but Nona’s mother had come from the ice fringes and her father’s clan hunted up on the glaciers, strangers both of them. ‘Mother says they just don’t like different.’

‘Those are ugly ideas for children to have in their heads.’ The juggler picked up his bag.

Nona stood, watching the apple in her hand but not seeing it. The memory held her. Her mother, in the dimness of their hut, noticing the blood on her hands for the first time. What’s that? Did they hurt you? Nona had hung her head and shook it. Billem Smithson tried to hurt me. This was inside him.

‘Best get along home to your ma and pa.’ Amondo turned slowly, scanning the huts, the trees, the barns.

‘My da’s dead. The ice took him.’

‘Well then.’ A smile, only half-sad. ‘I’d best take you home.’ He pushed back the length of his hair and offered his hand. ‘We’re friends, aren’t we?’

Nona’s mother let Amondo sleep in their barn, though it wasn’t really more than a shed for the sheep to hide in when the snows came. She said people would talk but that she didn’t care. Nona didn’t understand why anyone would care about talk. It was just noise.

On the night Amondo left, Nona went to see him in the barn. He had spread the contents of his bag before him on the dirt floor, where the red light of the moon spilled in through the doorway.

‘Show me how to juggle,’ she said.

He looked up from his knives and grinned, dark hair swept down across his face, dark eyes behind. ‘It’s difficult. How old are you?’

Nona shrugged. ‘Little.’ They didn’t count years in the village. You were a baby, then little, then big, then old, then dead.

‘Little is quite small.’ He pursed his lips. ‘I’ve two years and twenty. I guess I’m supposed to be big.’ He smiled but with more worry in it than joy, as if the world made no more sense and offered no more comfort to bigs than littles. ‘Let’s have a go.’

Amondo picked up three of the leather balls. The moonlight made it difficult to see their colours but with focus approaching it was bright enough to throw and catch. He yawned and rolled his shoulders. A quick flurry of hands and the three balls were dancing in their interlaced arcs. ‘There.’ He caught them. ‘You try.’

Nona took the balls from the juggler’s hands. Few of the other children had managed with two. Three balls was a dismissal. Amondo watched her turning them in her hands, understanding their weight and feel.

She had studied the juggler since his arrival. Now she visualized the pattern the balls had made in the air, the rhythm of his hands. She tossed the first ball up on the necessary curve and slowed the world around her. Then the second ball, lazily departing her hand. A moment later all three were dancing to her tune.

‘Impressive!’ Amondo got to his feet. ‘Who taught you?’

Nona frowned and almost missed her catch. ‘You did.’

‘Don’t lie to me, girl.’ He threw her a fourth ball, brown leather with a blue band.

Nona caught it, tossed it, struggled to adjust her pattern and within a heartbeat she had all four in motion, arcing above her in long and lazy loops.

The anger on Amondo’s face took her by surprise. She had thought he would be pleased – that it would make him like her. He had said they were friends but she had never had a friend and he said it so lightly … She had thought that sharing this might make him say the words again and seal the matter into the world. Friend. She fumbled a ball to the floor on purpose then made a clumsy swing at the next.

‘A circus man taught me,’ she lied. The balls rolled away from her into the dark corners where the rats live. ‘I practise. Every day! With … stones … smooth ones from the stream.’

Amondo closed off his anger, putting a brittle smile on his face. ‘Nobody likes to be made a fool of, Nona. Even fools don’t like it.’

‘How many can you juggle?’ she asked. Men like to talk about themselves and their achievements. Nona knew that much about men even if she was little.

‘Goodnight, Nona.’

And, dismissed, Nona had hurried back to the two-room hut she shared with her mother, with the light of the moon’s focus blazing all about her, warmer than the noon-day sun.

‘Faster, girl!’ The abbess jerked Nona’s arm, pulling her out of her memories. The hoare-apples had put Amondo back into her mind. The woman glanced over her shoulder. A moment later she did it again. ‘Quickly!’

‘Why?’ Nona asked, quickening her pace.

‘Because Warden James will have his men out after us soon enough. Me they’ll scold – you they’ll hang. So pick those feet up!’

‘You said you’d been friends with the warden since before Partnis Reeve was a baby!’

‘So you were listening.’ The abbess steered them up a narrow alley, so steep it required a step or two every few yards and the roofs of the tall houses stepped one above the next to keep pace. The smell of leather hit Nona, reminding her of the coloured balls Amondo had handed her, as strong a smell as the stink of cows, rich, deep, polished, brown.

‘You said you and the warden were friends,’ Nona said again.

‘I’ve met him a few times,’ the abbess replied. ‘Nasty little man, bald and squinty, uglier on the inside.’ She stepped around the wares of a cobbler, laid out before his steps. Every other house seemed to be a cobbler’s shop, with an old man or young woman in the window, hammering away at boot heels or trimming leather.

‘You lied!’

‘To call something a lie, child, is an unhelpful characterization.’ The abbess drew a deep breath, labouring up the slope. ‘Words are steps along a path: the important thing is to get where you’re going. You can play by all manner of rules, step-on-a-crack-break-your-back, but you’ll get there quicker if you pick the most certain route.’

‘But—’

‘Lies are complex things. Best not to bother thinking in terms of truth or lie – let necessity be your mother … and invent!’

‘You’re not a nun!’ Nona wrenched her hand away. ‘And you let them kill Saida!’

‘If I had saved her then I would have had to leave you.’

Shouts rang out somewhere down the steepness of the alley.

‘Quickly.’ The alley gave onto a broad thoroughfare by a narrow flight of stairs and the abbess turned onto it, not pausing now to glance back.

‘They know where we’re going.’ Nona had done a lot of running and hiding in her short life and she knew enough to know it didn’t matter how fast you went if they knew where to find you.

‘They know when we get there they can’t follow.’

People choked the street but the abbess wove a path through the thickest of the crowd. Nona followed, so close that the tails of the nun’s habit flapped about her. Crowds unnerved her. There hadn’t been as many people in her village, nor in her whole world, as pressed into this street. And the variety of them, some adults hardly taller than she was, others overtopping even the hulking giants who fought at the Caltess. Some dark, their skin black as ink, some white-blond and so pale as to show each vein in blue, and every shade between.

Through the alleys rising to join the street Nona saw a sea of roofs, tiled in terracotta, stubbled with innumerable chimneys, smoke drifting. She had never imagined a place so big, so many people crammed so tight. Since the night the child-taker had driven Nona and his other purchases into Verity she had seen almost nothing of the city, just the combat hall, the compound where the fighters lived, and the training yards. The cart-ride to Harriton had offered only glimpses as she and Saida sat hugging each other.

‘Through here.’ The abbess set a hand on Nona’s shoulder and aimed her at the steps to what looked like a pillared temple, great doors standing open, each studded with a hundred circles of bronze.

The steps were high enough to put an ache in Nona’s legs. At the top a cavernous hall waited, lit by high windows, every square foot of it packed with stalls and people hunting bargains. The sound of their trading, echoing and multiplied by the marble vaults above, spoke through the entrance with one many-tongued voice. For several minutes it was nothing but noise and colour and pushing. Nona concentrated on filling the void left as the abbess stepped forward before some other body could occupy the space. At last they stumbled into a cool corridor and out into a quieter street behind the market hall.

‘Who are you?’ Nona asked. She had followed the woman far enough. ‘And,’ realizing something, ‘where’s your stick?’

The abbess turned, one hand knotted in the string of purple beads around her neck. ‘My name is Glass. That’s Abbess Glass to you. And I gave my crozier to a rather surprised young man shortly after we emerged from Shoe Street. I hope the warden’s guards followed it rather than us.’

‘Glass isn’t a proper name. It’s a thing. I’ve seen some in Partnis Reeve’s office.’ Something hard and near invisible that kept the Corridor winds from the fight-master’s den.

Abbess Glass turned away and resumed her marching. ‘Each sister takes a new name when she is deemed fit to marry the Ancestor. It’s always the name of an object or thing, to set us apart from the worldly.’

‘Oh.’ Most in Nona’s village had prayed to the nameless gods of rain and sun as they did all across the Grey, setting corn dollies in the fields to encourage a good harvest. But her mother and a few of the younger women went to the new church over in White Lake, where a fierce young man talked about the god who would save them, the Hope, rushing towards us even now. The roof of the Hope church stood ever open so they could see the god advancing. To Nona he looked like all the other stars, only white where almost every other is red, and brighter too. She had asked if all the other stars were gods as well, but all that earned her was a slap. Preacher Mickel said the star was Hope, and also the One God, and that before the northern ice and the southern ice joined hands he would come to save the faithful.

In the cities, though, they mainly prayed to the Ancestor.

‘There. See it?’

Nona followed the line of the abbess’s finger. On a high plateau, beyond the city wall, the slanting sunlight caught on a domed building, perhaps five miles off.

‘Yes.’

‘That’s where we’re headed.’ And the abbess led away along the street, stepping around a horse pile too fresh for the garden-boys to have got to yet.

‘You didn’t hear about me all the way up there?’ Nona asked. It didn’t seem possible.

Abbess Glass laughed, a warm and infectious noise. ‘Ha! No. I had other business in town. One of the faithful told me your story and I made a diversion on my way back to the convent.’

‘Then how did you know my name? My real name, not the one Partnis gave me.’

‘Could you have caught the fourth apple?’ The abbess responded with a question.

‘How many apples can you catch, old woman?’

‘As many as I need to.’ Abbess Glass looked back at her. ‘Hurry up, now.’

Nona knew that she didn’t know much, but she knew when someone was trying to take her measure and she didn’t like things being taken from her. The abbess would have kept on with her apples until she found Nona’s limit – and held that knowledge like a knife in its sheath. Nona hurried up and said nothing. The streets grew emptier as they approached the city wall and the shadows started to stretch.

Alleyways yawned left and right, dark mouths ready to swallow Nona whole. However warm the abbess’s laughter, Nona didn’t trust her. She had watched Saida die. Running away was still very much an option. Living with a collection of old nuns on a windswept hill outside the city might be better than hanging, but not by much.

‘Master Reeve said that Raymel wasn’t dead. That’s not true.’

The abbess pulled her coif off in a smooth motion, revealing short grey hair and exposing her neck to the wind. She quickly threw a shawl of sequined wool about her shoulders.

‘Where did— You stole that!’ Nona glanced around to see if any of the passers-by would share her outrage but they were few and far between, heads bowed, bound to their own purposes. ‘A thief and a liar!’

‘I value my integrity.’ The abbess smiled. ‘Which is why it has a price.’

‘A thief and a liar.’ Nona decided that she would run.

‘And you, child, appear to be complaining because the man you were to hang for murdering is not in fact dead.’ Abbess Glass tied the shawl and tugged it into place. ‘Perhaps you can explain what happened at the Caltess and I can explain what Partnis Reeve almost certainly meant about Raymel Tacsis.’

‘I killed him.’ The abbess wanted a story but Nona kept her words close. She had come to talking so late her mother had thought her dumb, and even now she preferred to listen.

‘How? Why? Paint me a picture.’ Abbess Glass made a sharp turn, pulling Nona through a passage so narrow that a few more pounds about her middle would see the nun scraping both sides.

‘They brought us to the Caltess in a cage.’ Nona remembered the journey. There had been three children on the wagon when Giljohn, the child-taker, stopped at her village and the people gave her over. Grey Stephen had passed her up to him. It seemed that everyone she knew watched as Giljohn put her in the wooden cage with the others. The village children, both littles and bigs, looked on mute, the old women muttered, Mari Streams, her mother’s friend, had sobbed; Martha Baker had shouted cruel words. When the wagon jolted off along its way stones and clods of mud had followed. ‘I didn’t like it.’

The wagon had rattled on for days, then weeks. In two months they had covered nearly a thousand miles, most of it on small and winding lanes, back and forth across the same ground. They rattled up and down the Corridor, weaving a drunkard’s trail north and south, so close to the ice that sometimes Nona could see the walls rising blue above the trees. The wind proved the only constant, crossing the land without friendship, a stranger’s fingers trailing the grass, a cold intrusion.

Day after day Giljohn steered his wagon from town to town, village to hamlet to lonely hovel. The children given up were gaunt, some little more than bones and rags, their parents lacking the will or coin to feed them. Giljohn delivered two meals a day, barley soup with onions in the morning, hot and salted, with hard black bread to dip. In the evening, mashed swede with butter. His passengers looked better by the day.

‘I’ve seen more meat on a butcher’s apron.’ That’s what Giljohn told Saida’s parents when they brought her out of their hut into the rain.

The father, a ratty little man, stooped and gone to grey, pinched Saida’s arm. ‘Big girl for her age. Strong. Got a lick o’ gerant in her.’

The mother, whey-faced, stick-thin, weeping, reached to touch Saida’s long hair but let her hand fall away before contact was made.

‘Four pennies, and my horse can graze in your field tonight.’ Giljohn always dickered. He seemed to do it for the love of the game, his purse being the fattest Nona had ever seen, crammed with pennies, crowns, even a gleaming sovereign that brought a new colour into Nona’s life. In the village only Grey Stephen ever had coins. And James Baker that time he sold all his bread to a merchant’s party that had lost the track to Gentry. But none of them had ever had gold. Not even silver.

‘Ten and you get on your way before the hour’s old,’ the father countered.

Within the aforementioned hour Saida had joined them in the cage, her pale hair veiling a down-turned face. The cart moved off without delay, heavier one girl and lighter five pennies. Nona watched through the bars, the father counting the coins over and again as if they might multiply in his hand, his wife clutching at herself. The mother’s wailing followed them as far as the cross-roads.

‘How old are you?’ Markus, a solid dark-haired boy who seemed very proud of his ten years, asked the question. He’d asked Nona the same when she joined them. She’d said nine because he seemed to need a number.

‘Eight.’ Saida sniffed and wiped her nose with a muddy hand.

‘Eight? Hope’s blood! I thought you were thirteen!’ Markus seemed in equal measure both pleased to keep his place as oldest, and outraged by Saida’s size.

‘Gerant in her,’ offered Chara, a dark girl with hair so short her scalp shone through.

Nona didn’t know what gerant was, except that if you had it you’d be big.

Saida shuffled closer to Nona. As a farm-girl she knew not to sit above the wheels if you didn’t want your teeth rattled out.

‘Don’t sit by her,’ Markus said. ‘Cursed, that one is.’

‘She came with blood on her,’ Chara said. The others nodded.

Markus delivered the final and most damning verdict. ‘No charge.’

Nona couldn’t argue. Even Hessa with her withered leg had cost Giljohn a clipped penny. She shrugged and brought her knees up to her chest.

Saida pushed aside her hair, sniffed mightily, and threw a thick arm about Nona drawing her close. Alarmed, Nona had pushed back but there was no resisting the bigger girl’s strength. They held like that as the wagon jolted beneath them, Saida weeping, and when the girl finally released her Nona found her own eyes full of tears, though she couldn’t say why. Perhaps the piece of her that should know the answer was broken.