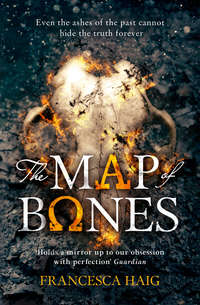

The Map of Bones

There’s no refuge in the refuge,

No peace behind those gates.

No freedom once you turn to them

Just living death, where the tanks await.

They throw you in a cage of glass

Not living, and not dying.

Trapped inside a floating hell

Where none can hear you crying.

Oh, you’ll never be hungry, you’ll never be thirsty

And the Council’s tanks will have no mercy.

Oh, you’ll never be tired, you’ll never be cold

And you’ll never ever ever grow old,

And the only price you’ll have to pay

Is to give your life away.

They drive us to the blighted land

Then bleed us with their tithes,

And if you go to the refuge

They’ll take your very lives.

The taboo has been forsaken

Within the refuge walls.

The machines have been awakened

And the Council plans to tank us all.

Oh, you’ll never be hungry, you’ll never be thirsty

And the Council’s tanks will have no mercy.

Oh, you’ll never be tired, you’ll never be cold

And you’ll never ever ever grow old,

And the only price you’ll have to pay

Is to give your life away.

When Leonard and Eva had played for us in the morning, we’d whooped along with some of the fast jigs, and clapped after some of the pieces where Leonard’s fingers had been at their swiftest. But none of us clapped now. The last notes slipped away, between the trees that encircled us like a gathered crowd. Our silence was the song’s best testament.

I wanted to send something into the world that wasn’t fire, or blood, or blades. Too many of my actions in recent months were bloodstained. The song was different – it was something we had built, rather than destroyed. But I knew that it was still a risk. If Leonard was caught, the song would hang him as surely as any act of violent resistance would. If Council soldiers heard him sing, or traced the treason back to him, the song would wind itself around his neck sure as a noose, and it would be his dirge, and Eva’s. Their twins’, too.

‘It’s a brave thing that the two of you’re doing,’ I said to Leonard, as we were packing up the camp in the dark.

He scoffed. ‘People fought and bled, on the island. I’m just an old blind man with a guitar.’

‘There are different kinds of courage,’ said Piper, emptying a flask of water on the fire, to ensure no telltale embers remained.

We said farewell to Leonard and Eva when we reached the road. A quick pressing of hands in the dark, and they were gone, heading east while we went west. Leonard was playing his mouth organ again, but distance rapidly dampened the music.

Over the next few days I found myself humming the chorus as I sharpened my dagger, matching the blade’s rasp to the beats of the song. I whistled the tune as I gathered wood for the fire. It was only a song, but it took hold in my mind like the ragweed that used to take over my mother’s garden.

CHAPTER 8

I’d never seen anything like the Sunken Shore. When we arrived, after five nights of walking, it was dawn. Below us, it looked as if the sea had crept gradually inwards, the land surrendering in messy increments. There was no clear point where the sea met the land, like in the steep cliffs that Kip and I had seen on the south-west coast, or even in the coves near the east coast’s Miller River. Instead there was only a jumble of peninsulas and spits, divided by inlets that grasped inland like the sea’s fingers. In some places, the land petered out into swampy shallows before giving in entirely to the sea. Elsewhere, low islands were humped with straggled grey-green growth that might have been grass or seaweed.

‘It’s low-tide now,’ Piper said to me. ‘Half of those islands will be under by noon. The shallows of the peninsulas too. If you get caught out on the wrong spit of land when the tide turns, you can find yourself in trouble.’

‘How does Sally live here? They haven’t allowed Omegas to live on the coast for years.’

‘See out there?’ Piper pointed to the farthest reaches of the broken coast, where the spits of land gave way to the water, a series of loosely linked islands barely keeping above the encroaching sea. ‘Right out there, on some of the bleaker spits, it’s too salty to farm and too swampy for good fishing, and paths are there one minute and gone in the next tide. You couldn’t pay Alphas to live out there. Nobody goes there. Sally’s been hiding out there for decades.’

‘It’s not just the landscape that keeps people away,’ Zoe said. ‘Look.’

She pointed out, further still. Beyond the scrappy spits of land, something in the water was glinting, reflecting the dawn back at itself. I narrowed my eyes and peered out. At first I thought it was some kind of fleet, masts massed in the sea. But they ignored the sea’s shifting and stayed perfectly motionless. Another glint of light. Glass.

It was a sunken city. Spires impaled the sea, the highest of them reaching thirty yards above the water. Others were barely glimpsed – just shapes at the surface with angles too precise to be rocks. The city went on and on, some spires standing alone, others clustered near to one another. Some seemed still to have glass in windows; most were just metal structures, cages of water and sky.

‘I took Sally’s boat out there once, years ago,’ Piper said. ‘It goes on for miles – the biggest of the Before cities that I’ve seen. Hard to imagine how many people must have lived there.’

I didn’t need to imagine. I could feel it, now that I was staring at the glass-sharpened sea. I could hear a submerged roar of presence, and absence. Did they die by fire, or water? Which came first?

We slept for the day on a promontory looking over the patchy welter of land and ocean. I dreamed of the blast, and when I woke I didn’t know where I was, or when. When Zoe came to rouse me for the last lookout shift before nightfall, I was already awake, sitting up with my blanket wrapped around me and my hands clutched together to quell their shaking. I was aware of her watching me as I walked to the lookout post. My movements felt jerky, and my ears still rang with the roar of the ravenous flames.

It was high tide, the sea had engulfed most of the furthest spits, leaving a network of tiny hillocks and rocks jutting out, so that the water was curdled by specks of land. The sunken city had disappeared altogether. Then, as the darkness advanced, I watched the tide retreat again. Lamps were lit in the Alpha villages on the slopes below us.

It wasn’t the underwater city that I was thinking of, as I watched the tide go out, the sea slinking away like a fox from a henhouse. I was thinking of Leonard’s passing comment that The Confessor had come from the Sunken Shore. Somewhere, only a few miles down the sloping coastline, was the place where she and Kip had grown up. She would have been sent away when they were split, but Kip had probably stayed on. This strange landscape would have been his home. As a child, he would have roamed these same hills. Perhaps he’d climbed up to this very viewpoint, and seen the tide go out, as I saw it now, more and more of the land being exposed to the moon’s gaze.

When it was full dark I woke Zoe and Piper.

‘Get up,’ I said.

Zoe gave a low groan as she stretched. Piper hadn’t even moved. I bent and yanked the blanket off him, throwing it down at his feet as I headed back to the lookout point.

We couldn’t risk a fire, within sight of the villages below, so we ate cold stew in the darkness. While Piper and Zoe packed up their things, I stood with my arms crossed, kicking at a tree root. Finally we moved off down the hill, towards the rich green slopes that edged the deepest inlets. We walked in silence. When, after a few hours, Piper offered me the water flask, I grabbed it without speaking.

‘What’s got you in such a foul mood?’ said Zoe.

‘I’m not,’ I said.

‘At least you’re making Zoe seem like a ray of sunshine in comparison,’ Piper said. ‘It’s a nice change.’

I didn’t say anything. I’d been gritting my teeth ever since we’d come within sight of the sea.

I remembered the day that Kip and I had first seen the ocean. We’d sat together, on the long grass overlooking the cliffs, and stared as the sea lapped at the edges of the world. And if he’d seen it before, he didn’t remember – it had been new to both of us.

Now I knew that the sea would have been a daily sight for him. He would have been used to it – probably didn’t even glance at it as he went about his daily business. The sea, which we’d sat and marvelled at together, would have been as familiar to him as the thatched roofs of his village.

It wasn’t only Kip that I had lost. Even the memories of what we had shared were being snatched from me, rendered false by what I’d learned about him.

Safest not to remember, I told myself, walking faster. Safest not to disturb the drowned city of my memories.

*

We had to navigate carefully through the unforgiving landscape. We weren’t only avoiding the Alpha villages, but also the inlets and fissures that penetrated even into the high slopes. Several times the route in front of us opened up into dark water, the gash of a crevasse. We walked all night, with only a brief rest at dawn. It was past noon when we left Alpha country and reached the edge of the straggling flatlands and the sea-mired spits. I stopped and looked back, one last time, at the Alpha villages behind us.

‘I heard it too,’ Zoe said, ‘when Leonard mentioned that The Confessor came from here.’

Piper was walking ahead of us, out of earshot. Zoe, one foot up on a rock, was waiting for me.

‘I figured you’d be curious, when we got here,’ she said.

‘It’s not just that,’ I said. I remembered her face at the campsite, when I’d caught her swaying with the music. I kept my eyes on the ground as we walked together. And for the first time, I ventured to say out loud what The Confessor had told me about Kip’s past. I needed to speak it. And I offered my secret to her like an apology, because I had intruded on her secret dreams.

I told her everything The Confessor had told me: how Kip had been cruel, and had delighted in having her branded and driven away. How, later, when he could afford it, he’d tracked her down and tried to arrange to have her locked in the Keeping Rooms for his own protection.

I told Zoe how Kip’s past had tangled everything that I felt. When I looked at the Sunken Shore and tried to imagine his childhood, I couldn’t recognise him at all. Instead of recognising Kip, I was recognising Zach. Zach and Kip had shared the same resentment and anger at having a twin who was a seer and refused to be split. I’d been fleeing from Zach, but the more I thought of Kip’s past, the more I saw Zach in him. And The Confessor – I had feared her most of all, but when I’d heard about her childhood, I recognised my own story. She’d been branded and exiled, just like me.

Everything was backwards. Everything was doubled, a mirror facing a mirror so that the picture regressed infinitely, and no end was possible.

When I’d emptied myself of words, Zoe stopped walking, turning again to face me, blocking my way.

‘What did you hope I was going to say to you, when you told me this?’ she said.

I had no answer.

‘Did you think I was going to let you cry on my shoulder,’ she went on, ‘and tell you it was all OK?’

She grabbed me, shook me slightly.

‘What difference does it make?’ she said. ‘What does it matter what he was like? Or The Confessor? There isn’t time for you to indulge in all of this soul-searching. We’re trying to keep you alive, and not get killed ourselves. We can’t do it with you moping around. You’re slipping further into the visions, too. We’ve both seen it – how they get to you. How you scream and shake, when you see the blast.’ She shook her head. ‘I’ve seen it happen before. You need to fight it. And you can’t do that if you’re obsessing over Kip. You’re still alive. He’s dead. And it sounds like he wasn’t such a great loss after all.’

I hit her, full in the face. I’d struck out at her once before, months ago, when she’d made a similarly disparaging comment about Kip. But that had been a chaotic grappling in the half dark. This was more precise: a single punch to the face. I didn’t know which of us was more surprised. Nonetheless, her instincts didn’t let her down: she ducked to the left, deflecting most of the blow, my fist grazing along her cheek and ear. Even so, my knuckle cracked against something hard – her cheekbone, or jawbone – and I heard myself yelp.

She didn’t strike back, just stood there, one hand raised to the side of her face.

‘You need to practise more,’ she said. She rubbed her cheek, opened her mouth wide to test the pain. A red mark was surfacing on her jaw. ‘And you’re still not following through enough.’

‘Shut up,’ I said.

‘Open and shut your fingers,’ she instructed, watching me as I winched my fist open and closed.

She took it and turned it over, methodically bending each finger. ‘It’s just bruised,’ she said, dropping my hand.

‘Don’t talk to me,’ I said. I shook my hand, half expecting to hear the rattle of bones knocked loose.

‘I’m glad to see you angry,’ she said, smiling. ‘Anything’s better than having you wandering around like a ghost.’

I thought of Leonard’s words to me. Girl, you’re hardly here.

‘Anyway, it’s not even me who you’re angry at,’ she said.

‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.’ I shouldered past her to follow Piper, who was nearly out of sight.

She called after me. ‘You’re angry at Kip. And it doesn’t even have anything to do with his past. You’re angry at him because he jumped, and left you behind.’

*

We walked in silence for hours. The peninsula that Piper led us to was really a string of islands, linked tenuously by a thin strip of land. The tide was already beginning to creep up the sides of the isthmuses, leaving just a narrow passage from one island to the next. In mid afternoon we set out across the final strip of stones, the last island ahead of us. It loomed tall, even now that the sea had claimed its lowest reaches. The tide was almost at its highest; the only way to reach the island was across a slim thread of rocks, already slippery with spray.

Piper was still ahead of us, already half way to the island. I turned back to face Zoe, who was just behind me.

‘When are you going to tell him about Kip?’

‘Keep moving,’ she said. ‘This path’ll be underwater in a few more minutes.’

I didn’t move.

‘When are you going to tell him?’ I said again. A wave splashed my leg, a shock of cold.

‘I figure you’ll do it yourself, soon enough,’ she said, pushing past me and clambering onwards on the slippery rock.

I should have been relieved. But now the secret was once again mine, so was the responsibility. I’d have to tell him myself. And to say it out loud again felt like an incantation: as if each time I uttered the words, I made Kip’s past more real.

CHAPTER 9

Piper and Zoe had paused on the brink of the final island. Piper blocked the way, crouching at the point where the isthmus met the wooded slope.

When I tried to edge past him, he stood and yanked at my jumper, pulling me back. ‘Wait,’ he said.

‘What are you doing?’ I said, shaking him off.

‘Look,’ he said, crouching again and peering at the path. I bent to see what he was so intent on.

He pointed out the strand of wire stretched across the width of the path, six inches above the ground. ‘Stay down,’ he said. Zoe, beside him, squatted on her heels. He leaned forward and tugged the wire.

The arrow passed a foot above our heads and disappeared into the sea. Piper stood, grinning. Somewhere on the island ahead of us, a bell was clanging. I looked back to the water. The arrow had not even left a ripple. If we’d been standing, it would have gone straight through us.

‘She’ll know we’re coming, at least,’ said Zoe. ‘But she won’t be happy that you wasted an arrow.’

Piper bent and pulled the wire again. Twice slowly, twice quickly, and slowly twice more. Up the hill, the bell sounded out the rhythm.

Three more times, as we crossed the island, Piper or Zoe halted us so that we could step over trip wires. Another time, I felt the trap even before Zoe warned me to step off the path. When I bent to examine the ground, I could sense a kind of insubstantiality to it: a confusion between air and earth. Crouching, I saw the layer of long willow twigs woven together and covered with leaves.

‘There’s a six-foot drop under there,’ Piper said. ‘Sharpened stakes planted at the bottom, too. Sally made Zoe and me dig it, when we were teenagers. Was a bitch of a job.’ He set off ahead of me. ‘Come on.’

It took us nearly an hour to cross the island, making our way up the forested slope and avoiding the traps. Eventually we ran out of land. The island had climbed to a peak at its southern edge, where a cliff dropped away to the sea in front of us. There was nothing beyond but the waves and the unlikely angles of the submerged city.

‘There,’ said Piper, pointing through the final trees. ‘Sally’s place.’

I could see nothing but the trees, their pale trunks blotched with brown like an old man’s hands. Then I saw the door. It was low, and half-concealed by the boulders that clustered at the cliff’s edge. It stood impossibly close to the end of the bluff – it looked like a doorway into nothingness, and was so faded and battered by the coastal winds that the wood was bleached to the same shade as the salt-parched grasses around it. It had been built to take advantage of the cover of the boulders, so that at least half of the building must have hung out over the edge of the cliff itself.

Zoe whistled, the same rhythm that Piper had sounded on the warning bell: two slow notes, two quick, and two slow.

The woman who opened the door was the oldest person I’d ever seen. Her hair was sparse enough that I could see the curve of scalp beneath it. Around her neck, the skin was draped like a cowl. Even her nose looked tired, drooping at the tip like melted candle wax. I was fairly sure that her forehead bore no brand, but it was hard to tell: age had branded her now, her forehead cragged with wrinkles. The loose flesh of her eyelids hung so low over her eyes that I imagined they must disappear altogether when she smiled.

But she wasn’t smiling now. She was looking at us.

‘I hoped you wouldn’t come,’ she said.

‘Nice to see you too,’ said Zoe.

‘I knew you wouldn’t come unless you were desperate,’ the woman said. She came forward, a lurch in her step. Both legs were twisted, the joints gnarled and fused. She embraced Zoe first, and then Piper. Zoe closed her eyes when Sally held her. I tried to picture Zoe and Piper as they must have been when, ten years old and on the run, they first came to Sally. I wondered how much the old woman had seen them change. The world was a flint on which they had been sharpened.

‘This is the seer?’ Sally said.

‘This is Cass,’ said Piper.

‘I haven’t stayed safe all these years by bringing strangers into my home,’ she said.

She had to balance her speech with her breathing, so the words came slowly. Sometimes she paused between each syllable, the noisy breaths taking their time. Each breath a sigh.

‘You can trust me,’ I said.

She stared at me again. ‘We’ll see.’

We followed her inside the house. When she shut the door behind us, the whole building shook. I thought again of the cliff underneath us, and the sea clawing at the rocks.

‘Relax,’ said Piper. I hadn’t even realised that I was clutching the doorframe. ‘This place has been here for decades. It’s not going down the cliff tonight.’

‘Even under the weight of an uninvited guest,’ added Sally. She turned away and shuffled into the kitchen. Her footsteps on the floor were hollow – only wood between her and the cliff’s plunge. ‘Since you’re all here, I suppose I’d better get some food ready.’

As she busied herself at the table, I looked at the closed door by the stove. No noise came from within, but I could feel, like a draught on the back of my neck, another presence in the house.

‘Who else is here?’ I said.

‘Xander’s resting,’ Sally said. ‘He was up all last night.’

‘Xander?’ I said.

Sally raised an eyebrow at Piper.

‘You didn’t tell her about Xander?’

‘Not yet.’ He turned to me.

‘Remember I told you, on the island, that we’d had two other seers? And the younger one had been brought to the island before he was branded?’

I nodded.

‘Xander was useful for undercover work,’ Piper went on, ‘but we didn’t want to involve him in anything too important.’

‘Was he too young?’

‘You think we had the luxury of sparing the young ones that kind of responsibility?’ He laughed. ‘Some of our scouts on the mainland were barely in their teens. No – and it wasn’t even that Xander couldn’t be trusted, really. We never thought he’d deliberately betray us. But he was always volatile.’

‘It got worse, in the last few years,’ Zoe said. ‘But even before that, he was always jumpy. Skittish, like a horse that’s seen a snake.’

‘It was a shame,’ said Piper.

‘A shame for him, to be so troubled?’ I asked. ‘Or for you, that you couldn’t use him as you’d have liked?’

‘Can’t it be both?’ Piper said. ‘Anyway, he did what he could for us. We based him on the mainland. Even without his visions, it was useful to have someone unbranded who could pass for an Alpha. And sometimes his visions came in useful, too. But we had to bring him here, in the end. He couldn’t work anymore, and Sally said she’d take him.’

‘Why do you keep talking about him in the past tense? He’s here now, isn’t he?’

‘You’ll see soon enough,’ Sally said, hobbling across the kitchen and opening the door to the room beyond.

*

A boy sat on the bed, his back to us. He had thick dark hair like Piper’s, tightly curled, but it was longer, and stood in high tufts, like the peaks of beaten egg whites. The window above the bed looked out over the water, and the boy didn’t turn away from it as we entered.

We moved closer. Piper sat next to him on the bed, ushering me to sit beside him.

Xander was perhaps sixteen. His face still had the softness of a child. Like Sally, he was unbranded. When Piper greeted him, he didn’t look at us, or respond at all. His eyes darted from side to side, as if following the flight of some invisible insect above our heads.

I wasn’t sure whether what I sensed about him was evident to everyone, or whether it was only seers that would feel it. The brokenness inside him. Sally had said that he was resting, but there was no rest here. Only terror. The frantic buzzing of Xander’s mind was like a wasp trapped in a jar.

Zoe hung back in the doorway. I saw her mouth tighten as she watched the fidgeting of Xander’s long fingers, ceaselessly kneading the air. And I remembered what she’d said to me, about how the visions affected me: I’ve seen it happen before.

Piper stilled one of Xander’s hands with his own.

‘It’s good to see you again, Xander.’

The boy opened his mouth, but no words came. In the silence, I could almost hear the discordant jangling of his mind.

‘Do you have any news for us?’ Piper asked.