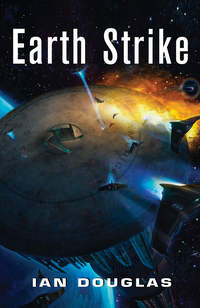

Earth Strike

And until that happened, humans were forbidden to have any contact whatsoever with the Aglestch.

The problem was, in fifty-five years an active and spirited trade had sprung up between the Aglestch worlds and the nearest star systems colonized by humans. StarTek and Galactic Dynamics, the trading corporations involved, hadn’t wanted to give up their lucrative contracts for Agletsch art and basic technical information. A Terran naval task group had been deployed to protect human trade routes in the region, and the Confederation Diplomatic Corps had made overtures to the Aglestch Collective about maintaining trade and diplomatic contact apart from Sh’daar oversight.

The result had been the disastrous Battle of Beta Pictoris, in 2468, the equivalent, in human eyes, of reaching out to shake hands and pulling back a bloody stump.

And for thirty-six years now, the war had continued … with a very few minor victories, and with a very great many major defeats. Humankind’s principle foes so far had been the Turusch va Sh’daar, a different Sh’daar client species that first had made its appearance thirty years before, at the Battle of Rasalhague. The First Interstellar War, as the news agencies had termed it back home, was not going well.

The infant planetary system of Beta Pic had been just sixty-three light years from Sol, the furthest humans had yet ventured from their homeworld, a microscopic step when compared with the presumed extant of the galaxy-spanning Sh’daar. Rasalhague had been closer still—forty-seven light years.

And Eta Boötis was only thirty-seven light years from Sol. The enemy was closing in, relentless, remorseless.

In 2367, the Terran Confederation had incorporated 214 interstellar colonies and perhaps a thousand research and trade outposts on planets scattered across a volume of space roughly one hundred light years across and perhaps eighty deep, a volume embracing almost eight thousand star systems, the majority of which had never even been visited by humans. And after less than four decades of bitter fighting, Confederation territory had dwindled by perhaps a quarter.

Humans still knew almost nothing about the Sh’daar—so far as was known, no human had ever even seen one—but their brief contact with the Agletsch had suggested that the Sh’daar presence might well encompass several hundred billion stars. Whether you called it a galactic empire or something else, in terms of numbers and resources, it seemed to pose an insurmountable threat.

The sheer impossibility of the Confederation fighting such an overwhelmingly vast and far-flung galactic power had strongly affected human culture and government, deeply dividing both, and affecting the entire Confederation with a kind of social depression, a plummeting morale that was difficult to combat, difficult to shoulder.

And one symptom of plunging morale was the increasing micromanagement out of C3—Confederation Central Command—on Earth. All military vessels now carried one or more Senate liaisons, like Quintanilla, to make certain the Senate’s orders were properly carried out.

If anything, direct Senate oversight of the military had made the morale problem even worse.

And that was why Koenig was concerned about his flag captain speaking his pessimism in front of the bridge personnel.

“We’ll know more when we rescue Gorman and his people,” Koenig added after a thoughtful pause, stressing the word when, rejecting the word if. “The scuttlebutt is that his Marines captured some Tush officers. If so, that could give us our first real insight into the enemy psychology since this damned war began.”

“Tush” or “Tushie” was military slang for the Turusch … one of the cleaner of a number of popular epithets. He saw Olmstead’s head come up in surprise at hearing a flag officer use that kind of language.

“Yes, sir,” Buchanan said.

“So we play it by the op plan,” Koenig added, speaking with a confidence he didn’t really feel but which he hoped sounded inspiring. “We go in, kick Trash ass, and pull our people and their prisoners out of there. Then we hightail for Earth and let the damned politicians know that the Galactics can be beaten.”

He grinned at Buchanan’s avatar. He suspected that the Captain had spoken aloud specifically to give Koenig a chance to say something inspiring. A cheap and theatrical trick, but he wasn’t going to argue with the psychology. The crew was nervous—they knew what they were in for at Eta Boötis—and hearing their admiral’s confidence, even an illusion of confidence, was critical.

On the battlespace display, five more ships appeared—the destroyer Andreyev, the frigates Doyle, Milton, and Wyecoff, and the troopship Bristol.

They would be ready to accelerate for the inner system soon.

VFA-44 Dragonfires

Eta Boötis System

0421 hours, TFT

Lieutenant Gray checked his time readouts, both of them. Time—the time as measured back on board America—was, as expected, flashing past at an insane pace, thirteen times faster, in fact, than it was passing for him.

In its high-G sperm-mode configuration, the SG-92 Starhawk’s quantum-gravitic projectors focused an artificial curvature of spacetime just ahead of the ship’s rounded prow—in effect creating a gravitational singularity that moved ahead of the fighter, pulling it forward at dizzying accelerations.

Accelerating at 50,000 gravities had boosted his Starhawk to near-light velocity in ten minutes. For the next hour, then, he’d been coasting at .997 c … except that the mathematics of time dilation reduced the time actually experienced on board the hurtling fighter to 0.077402 of that—or exactly four minutes, thirty-eight point six seconds.

Put another way, for every minute experienced by Trevor Gray in his tiny sealed universe of metal and plastic, almost thirteen minutes slipped past in the non-accelerated world outside. Since launching from the America, the Blue Omega fighter wing had traveled over a billion kilometers, nearly eight astronomical units, in what seemed like less than ten minutes.

Through the Starhawk’s optics, the universe outside looked very strange indeed.

Directly ahead and astern and to either side, there was nothing, a black and aching absence of light. All of the stars of the sky appeared to have been compressed into a frosty ring of light forward by the gravfighter’s near-c velocity. Even Eta Boötis itself, directly ahead, had been reshaped into a tight, bright circle.

And, despite the expectations of physicists from centuries ago, there was a starbow—a gentle shading of color, blue to deep violet at the leading edge of the starlight ring, and deep reds trailing. Theoretically, the starlight should all have appeared white, since visible light Doppler-shifted into invisibility would be replaced by formerly invisible wavelengths. In practice, though, the light of individual stars was smeared somewhat by the shifting wavelengths, creating the color effect known as the starbow.

Gray could have, had he wished, ordered the gravfighter’s AI to display the sky corrected for his speed, but he preferred the soft rainbow hues. Most fighter pilots did.

When the fighter was under acceleration, the sky ahead looked even stranger. Gravitational lensing twisted the light of stars directly ahead into a solid, bright ring around the invisible pseudomass in front of the ship, even when the craft was still moving at nonrelativistic speeds. For now, though, the effect was purely an artifact of the Starhawk’s speed—an illusion similar to what happened when you flew a skyflitter into a rainstorm, where the rain appeared to sleet back at an angle even when it was in fact falling vertically. In this case, it was photons appearing to sleet backward, creating the impression that the entire sky was crowded into that narrow, glowing ring ahead.

He checked the time again. Two minutes had passed for him, and almost half an hour for the rest of the universe.

He felt … lonely.

Technically, his fighter was still laser taclinked with the other eleven Starhawks of Blue Omega Flight, but communication between ships at near-c was difficult due to the severely Dopplered distortions in surrounding spacetime. The other fighters should be exactly matched in course and speed, but their images, too, were smeared into that light ring forward because their light, too, was traveling just three thousandths of a percent faster than Gray’s ship. Some low-level bandwidth could be held open over the laser channels for AI coordination, but that was about it. No voice. No vid. No avatars.

Just encircling darkness, Night Absolute, and the Starbow ahead.

The hell of it was, Gray was a loner. With his history, he damned near had to be. By choice he didn’t hang out much with the other pilots in the ready room or flight officers’ lounge. When he did, there was the inevitable comment about his past, about where he’d come from … and then he would throw a punch and end up getting written up by Allyn, and maybe even getting pulled from the flight line.

Better by far to stay clear of the other pilots entirely, and avoid the hassle.

But now, when the laws of physics stepped in like God Almighty to tell him he couldn’t communicate with the others, he found he missed them. The banter. The radio chatter.

The reassurance that there were, in fact, eleven human souls closer than eight astronomical units away.

He could, of course, have called the avatars of any or all of the others. Copies of their PAs—their Personal Assistants—resided within his fighter’s AI memory. He could hold a conversation with any of them and be completely unaware that he was speaking to software, not a living person … and he would know that the software would report the conversation with perfect fidelity to the person when the comnet channels opened later on.

But avatars weren’t the same. For some it was, but not for Trevor Gray.

Not for a Prim.

He closed his eyes, remembering the last time. He’d been in the lounge of the Worldview, a civilian bar adjacent to the spaceport at the SupraQuito space elevator. He and Rissa Schiff had been sitting in the view blister, just talking, with Earth an unimaginably beautiful and perfect sphere of ocean-blue and mottled cloud-white gleaming against the night. The two had been in civilian clothing, which, as it turned out, had been lucky for him. Lieutenants Jen Collins and Howie Spaas had walked up, loud and uninvited, also in civvies, and both blasted on recs.

“Geez, Schiffie,” Collins had said, her voice a nasal sneer. “You hang around with a Prim loser like this perv, you’re gonna get a bad name.” Spaas had snickered.

Gray had stood, his fists clenched, but he’d kept a lid on it. Allyn had lectured him about that the last time he’d gotten into trouble with other squadron officers … the need to let the insults slide off. The shipboard therapist she’d sent him to had said the same thing. Other people could hurt him, could get through his shields only if he let them.

“Who asked you, bitch?” Gray had said quietly.

“Ooh, I’m afraid,” Spaas said, grinning. “Hey, Riss … you need to be careful around creeps like this. A fucking Prim monogie. You’re never gonna get any …”

It had been worth it, decking Spaas. It really had. It had been worth having the Shore Patrol show up, worth the off-duty restriction to quarters for a week, worth the extra watches, even worth the searing new asshole the skipper had given him. Commander Allyn could have put him up for court martial, but she’d chosen to give him a good old-fashioned ass-chewing instead.

He still remembered that next morning in her office. “The Navy appreciates pilots who want to fight, Gray,” she’d told him. “But the idea is to fight the Turusch, not your shipmates. You hear me? You have one more chance. Blow it and you get busted back to the real Navy.”

Prim monogie.

Yeah, it had been worth it.

Chapter Two

25 September 2404

CIC, TC/USNA CVS America

Eta Boötean Kuiper Belt

0428 hours, TFT

Admiral Koenig took a final look at the heavens revealed through the encircling viewalls of America’s CIC. Eta Boötis gleamed in amber splendor directly ahead. Off to port, red-golden Arcturus shone as well—not as brilliantly as Eta Boötis, but still with twice the brightness of Venus as seen from Earth at its closest.

Someday, we’ll make it back there, Koenig thought, gazing for a moment at Arcturus, just three light years distant. He still felt the bitterness of that last, desperate fight at Arcturus Station last year.

That was for later. Right now, it was Mufrid that required his full attention.

Two of the naval transports never had checked in … which might mean they’d suffered malfunction or disaster en route from Sol, or, more likely, that they’d emerged from Alcubierre Drive more than 1.3 light hours from the America.

It would be the transports, he thought—the entire reason for coming to Eta Boötis in the first place. Still, if they’d made it this far, they would follow the task force in. Gray couldn’t hold up the mission any longer waiting for them.

Over the course of the past eighty minutes, the task force had been pulling slowly together, until most occupied a rough sphere half a million kilometers across. All were now electronically connected through the laser-link tacnet, though the most distant vessels would lag fifteen minutes behind in receiving any message from the flagship.

“Captain Buchanan,” Koenig said, “you may inform the ship that we are about to get under way.”

“Aye, aye, Admiral,” Buchanan’s voice replied immediately.

It was a formality. All hands had been at maneuvering stations since their arrival in-system. The announcement went out silently, spoken through each person’s in-head e-links. “Now hear this, now hear this. All hands, prepare for immediate acceleration under Alcubierre Drive.”

“Make to all vessels on the net,” Koenig told the ship’s AI. “Engage Alcubierre Drive, acceleration five hundred gravities, on my mark … and three … two … one … mark!”

That mark was variable, depending on how long it took for the lasercom command to crawl across emptiness from the America. The massive carrier began moving forward first, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Pauli and the frigates Psyché and Chengdu, close abeam. One by one the other vessels began falling into train, the sphere slowly elongating into an egg shape as more and more vessels got the word and engaged their drives.

The principles of the Alcubierre Drive had been laid down by a Mexican physicist in the last years of the twentieth century. It was old tech compared to the artificial singularities employed by modern gravfighters, but it used the same principles. Essentially, drive projectors compressed spacetime ahead of each vessel, and expanded spacetime astern, creating a bubble in the fabric of space that could move forward at any velocity, ignoring the usual constraints imposed by the speed of light because everything within the bubble, imbedded in that patch of spacetime, was motionless compared to the space around it.

Practical considerations—both size and mass—limited Alcubierre acceleration to five hundred gravities. At that rate, America would be pushing the speed of light after sixteen hours, thirty-seven minutes.

However, after that length of time they would have traveled almost sixty astronomical units, which meant they wouldn’t have time to decelerate in to the target.

Instead, they would accelerate constantly for just over nine hours, at which point they’d be moving at .54 c, then reverse their drives and decelerate for the same period.

They would arrive in the vicinity of Eta Boötis IV ten hours after fighter wing Blue Alpha had engaged the enemy.

And until that time, Blue Omega Strike Force would be fighting the enemy alone.

VFA-44 Dragonfires

Eta Boötis System

1015 hours, TFT

For Trevor Gray, half an hour passed. In the universe outside, six and a half hours slipped away, and with them another 7 billion kilometers, or forty-six more astronomical units.

He was just over three quarters of the way to the target.

He wondered how the other eleven pilots of the squadron were doing … but shrugged off the question. His AI would alert him if the tenuous data link with another fighter snapped. That hadn’t happened yet, so the chances were good that the others all were out there, as bored and, paradoxically, as nervous as he was.

In another eleven subjective minutes, he would begin the deceleration phase of the strike, but that would be handled by his AI. Coordination of the timing within the flight of twelve gravfighters had to be exact, or they would drop down to combat speed scattered all over the sky, rather than in attack formation.

He spent the time studying the world now just two and a half light hours ahead.

His AI had last updated his target data from America’s CIC just before the squadron had boosted, which meant that his information about the enemy’s strength and dispositions around Eta Boötis were now a full seventeen hours out of date. That was the tricky aspect to near-c deployment; once you boosted to relativistic speeds, you couldn’t be exactly sure of what you were getting into until you were nearly there.

His Starhawk’s forward sensors, at this speed, were all but useless. Radiation from ships around Eta Boötis IV was strongly distorted both by relativistic effects and by the “dustcatcher,” a high-gravity zone maintained ahead of the fighter at near-c even when the ship wasn’t accelerating, to trap or deflect dust and gas in the gravfighter’s path. Any information that made it to the fighter’s sensors was lost in the light-smeared ring representing the star dead ahead.

According to the most recent electronic intelligence, though, there were fifty-five ships there—almost certainly all Turusch—orbiting Eta Boötis IV or on final approach. And there was a way to slightly improve the view.

He moved his hands within the control field. On the mirrored black surface of his Starhawk, three sensor masts detached from the hull and swung out and forward, each two meters long at the start, but unfolding, stretching, and growing to reach a full ten meters from the ship. The receivers at the ends of the masts, spaced equidistant around the fighter, extended far enough out to let them look past the nebulous haze of the dustcatcher. As Gray watched, the inner circle of light on the cockpit display grew sharper and brighter. Incoming radiation was still being distorted by the Starhawk’s velocity, of course, but now he could see past the distortion of the singularity, and even take advantage of the dustcatcher’s gravitational lensing effect.

Bright flashes silently popped and flared across the display now, however. Extended, the sensor masts were striking random bits of debris—hydrogen atoms, mostly, adrift in the not-quite-perfect vacuum of space and made deadly by the gravfighter’s speed. Impact at this speed with something as massive as a meteoric grain of sand could destroy the mast; his AI had to work quickly.

The data came up less than five seconds later, and with a feeling of relief Gray retracted the sensor masts back into the hull, safe behind the blurring distortion of the dustcatcher. The fighter’s artificial intelligence had sampled the incoming radiation, sorting through high-energy photons to build a coherent picture of what lay ahead.

Resolution was poor. Only a few ship-sized targets—the most massive—could be separated from the distortion-induced static. The AI did its best to match up the handful of targets it could see now with those that had been visible to America’s sensors hours earlier. By combining the America data with this fresh, if limited, glimpse, the AI could make a close guess at the orbits of a few of the enemy vessels, and predict where they would be—assuming no changes in orbit—in another 136-plus minutes, objective.

Fifteen targets. Gray had hoped there would be more, but it was something with which to work. Fifteen large starships appeared to be in stable, predictable orbits around the target world, their orbital data precise enough to allow a clear c-shot at them. Of those fifteen, six, the data predicted, would be on the far side of the target planet 136 objective minutes from now, so they were off the targeting list. The remaining nine, however, were fair game.

The actual targeting and munitions launch were handled automatically by the AI-net, requiring only Gray’s confirmation for launch. So long as there was no override from Commander Allyn, all eleven Starhawks would be contributing to the PcB, the Pre-engagement c Bombardment.

Release would be at a precisely calculated instant just before deceleration. He checked the time readouts again. Five minutes, twelve seconds subjective to go.

He worked for a time trying to get a clearer look at the objective. The visual image was blurred, grainy, and heavily pixilated, but he could make out the planet, Eta Boötis IV, sectioned off by green lines of longitude and latitude, the shapes of continents roughed in. Fifteen red blips hung in space about the globe, most so close they appeared to be just skimming the globe’s surface, and he could see their motions, second to second, as the AI updated their locations. A white blip on the surface marked the objective—General Gorman’s slender beachhead. It was on the side of the planet facing Gray at the moment, the planet’s night side, away from the local sun, but in another two hours objective, it would be right on the planet’s limb—local dawn.

Additional red blips flicked on, a cloud of them, indistinct and uncertain, centered around and over Gorman’s position. Those marked enemy targets for which there was no orbital data and that most likely were actively attacking the Marine perimeter. Or rather, they had been 136 minutes ago, when the photons revealing their positions had left Eta Boötis IV. For all Gray knew, the perimeter had collapsed hours ago, and the squadron was about to make a useless demonstration at best, fly into a trap at worst. He shoved the thought aside. They were committed, had been committed since boosting clear of the America. They would know the worst in another few subjective minutes.

He opened his fighter’s library, calling up the ephemeris for Eta Boötis and its planets. He scrolled quickly through the star data, then slowed when he reached the entry for the fourth planet.

PLANET: Eta Boötis IV

NAME: Al Haris al Sama, (Arabic) “Guardian of Heaven”; Haris; Mufrid.

TYPE: Terrestrial/rocky; sulfur/reducing

MEAN ORBITAL RADIUS: 2.95 AU; Orbital period: 4y 2d 1h

INCLINATION: 85.3 ; ROTATIONAL PERIOD: 14h 34m 22s

MASS: 1.8 Earth; EQUATORIAL DIAMETER: 24,236 km = 1.9 Earth

MEAN PLANETARY DENSITY: 5.372 g/cc = .973 Earth

SURFACE GRAVITY: 1.85 G

SURFACE TEMPERATURE RANGE: ~30ºC – 60ºC.

SURFACE ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE: ~1300 mmHg

PERCENTAGE COMPOSITION: CO2 30.74; SO2 16.02; SO3 14.11; NH4 13.63; OCS 12.19; N2 5.55; O2 3.85; CH3 2.7; Ar 0.2; CS2 variable; others <800 ppm

AGE: 2.7 billion years

BIOLOGY: C, N, H, S8, O, Se, H2O, CS2, OCN; SESSILE PHOTOLITHOAUTOTROPHS IN REDUCING ATMOSPHERE SYMBIOTIC WITH VARIOUS MOBILE CHEMOORGANOHETEROTROPHS AND CHEMOSYNTHETIC LITHOVORES …