Sketch of the History of the Knights Templars

At the head of the Order stood the Grand Master, who, like the General of the Jesuits in modern times, was independent of all authority but that of the sovereign pontiff. The residence of the Grand Master was the city of Jerusalem; when the city was lost, he fixed his seat at Antioch, next at Acre, then at the castle of the Pilgrims,12 between Caiphas and Cæsarea, and finally in Cyprus, for his duty required him to be always in the Holy Land. The Grand Master never resided in Europe until the time of Jacques de Molay. The power of the Grand Master was considerable, though he was very much controuled by the chapter, without whose consent he could not dispose of any of the higher offices, or undertake any thing of importance. He could not, for instance, take money out of the treasury, without the consent of the prior of Jerusalem; he could neither make war or truce, or alter laws, but with the approbation of the chapter. But the Grand Master had the right of bestowing the small commands, the governments of houses of the Order, and of selecting the brethren who should form the chapter, which power was again controuled by there being always assigned him two brethren as assistants, who, with the Seneschal, were to form a part of every chapter. The Order was aristocratic rather than monarchic; the Grand Master was like a Doge of Venice, and his real power chiefly depended on his personal qualities; he had, however, many distinctions; the greater part of the executive power was in his hands – in war he was the commander-in-chief; he had, as vicar-general of the Pope, episcopal jurisdiction over the clergy of the Order; he ranked with princes, and his establishment corresponded thereto; he had for his service four horses, a chaplain, two secretaries, a squire of noble birth, a farrier, a Turcopole and cook, with footmen, and a Turcoman for a guide, who was usually fastened by a cord to prevent his escape. When the Grand Master died, his funeral was celebrated with great solemnity by the light of torches and wax tapers, – an honour bestowed by the Order on no other of its Members. All the Knights and Prelates were invited to assist. Each Brother who was present was to repeat two hundred Pater Nosters within the space of seven days, for the repose of the soul of the deceased; and one hundred poor persons were fed at home, at the expense of the Order, with the same design.13

Each province of the Order had a Grand Prior, who represented in it the Grand Master; each house had its Prior at its head, who commanded its Knights in war, and presided over its chapters in peace. In England, the Grand Prior sat in Parliament as a Peer of the Realm. To complete this sketch of the Order, we may remark, that except Scandinavia, (for they had some possessions in Hungary,) there was not a country in Europe in which the lavish piety of princes and nobles had not bestowed on the Templars a considerable portion of the wealth of the state; for in every province the Order had its churches and chapels – the number of which was in the year 1240, as great as 1050 – villages, farm-houses, mills, corn-lands, pastures, woods, rights of venison, and fisheries.14 The revenues of the Templars in England in 1185, as given by Dugdale, will afford some idea of their wealth. The entire annual income of the Order has been estimated at not less than six millions sterling.

It cannot be denied, that this enormous wealth, together with the luxury and other evils which it engendered, provoked the hatred of the secular clergy and laity, and paved the way to the spoliation of the Order. In 1252, the pious pope-ridden Henry III. of England said, that the prelates and clergy in general, but especially the Templars and Hospitallers, had so many liberties and privileges, that their excessive wealth made them mad with pride; he added, that what had been bestowed imprudently, ought to be prudently resumed, and declared his intention of revoking the inconsiderate grants of himself and his predecessors. The Grand Prior of the Templars replied, "What sayest thou, my Lord the King? Far be it that so discourteous and absurd a word should be uttered by thy mouth. So long as thou observest justice, thou mayest be a king, and as soon as thou infringest it, thou wilt cease to be a king." A bold expression certainly, but the Prior knew his man well, and he would hardly have spoken so to the son of Henry. The anecdote of Richard I. bestowing his daughter Pride in marriage on the Templars, is well known; and numerous traits of their haughtiness, avarice, luxury, and other of the current vices, may be found in the writers of the thirteenth century; but till the final attack was made, no worse charge was brought against them, unless such is implied in a bull of Pope Clement IV. in 1265, which is, however, easily capable of a milder interpretation. Mr. Raynouard asserts, too, that the proverbial expression bibere Templariter is used by no writer of the thirteenth century. In this he is preceded by Baluze and Roquefort, who maintain, that, like bibere Papaliter, it only signified to live in abundance and comfort.

PERSECUTION OF THE TEMPLARS

CHAP. III.

The Persecution of The Templars

When Acre fell in 1292, the Templars, having lost all their possessions and a great number of their members in the Holy Land, retired with the other Christians to Cyprus. Having probably seen the folly of all hope of recovering the Holy Land, they grew indifferent about it; few members joined them from Europe, and it is more than probable that they meditated a removal of the chief seat of the Order to France.15 The Hospitallers, on the other hand, with more prudence, as events showed, resolved to continue the war against the infidels, and they attacked and conquered Rhodes; while the Teutonic knights transferred the sphere of their pious warfare to Prussia against its heathen inhabitants. Thus, while the Templars were falling under the reproach of being luxurious Knights, their rivals rose in consideration, and there was an active and inveterate enemy ready to take advantage of their ill-repute.

Philip the Fair, a tyrannical and rapacious prince, was at that time on the throne of France. His darling object was to set the power of the monarchy above that of the church. In his celebrated controversy with Pope Boniface, the Templars had been on the side of the Holy See. Philip, whose animosity pursued Boniface even beyond the grave, wished to be revenged on all who had taken his side; moreover, the immense wealth of the Templars, which he reckoned on making his own if he could destroy them, strongly attracted the king, who had already tasted of the sweets of the spoliation of the Lombards and the Jews; and he probably, also, feared the obstacle to the perfect establishment of despotism which might be offered by a numerous, noble, and wealthy society, such as the Templars formed. Boniface's successor, Clement V. was the creature of Philip, to whom he owed his dignity, and at his accession had bound himself to the performance of six articles in favour of Philip, one of which was not expressed. It was probably inserted without any definite object, and intended to serve the interest of the French monarch on any occasion which might present itself.

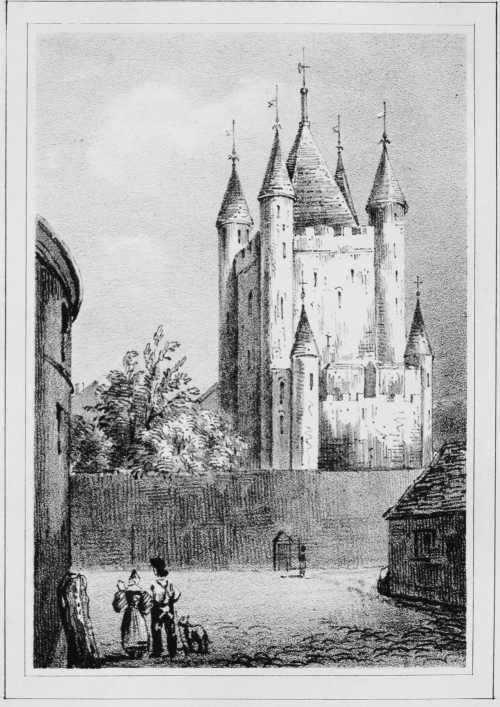

LA TOUR DU TEMPLE À PARIS

It had been the object of Pope Boniface to form the three Military Orders into one, and he had summoned them to Rome for that purpose, but his death prevented it. Clement, on this, June 6, 1306, addressed the Grand Masters of the Templars and the Hospitallers, inviting them to come to consult with him about the best mode of supporting the Kings of Armenia and Cyprus. He desired them to come as secretly as possible, and with a very small train, as they would find abundance of their Knights this side the sea; and he directed them to provide for the defence of Limisso in Cyprus during their short absence. Fortunately perhaps for himself and his Order, the Master of the Hospitallers was then engaged in the conquest of Rhodes, but Jacques de Molay,16 the Master of the Templars, immediately prepared to obey the mandate of the Pope, and he left Cyprus with a train of 60 Knights, and a treasure of 150,000 florins of gold, and a great quantity of silver money, the whole requiring twelve horses to carry it.17 He proceeded to Paris, where he was received with the greatest honours by the King, and he deposited his treasure in the Temple of that city. It is, as we have said, not impossible that it was the intention of Molay to transfer the chief seat of the Order thither, and that he had, therefore, brought with him its treasure and the greater part of the members of the chapter; and indeed it is difficult to say how early the project of attacking the Templars entered into the minds of Philip and his obsequious lawyers, or whether he originally aimed at more than mulcting them under the pretext of reformation: and farther, whether the first informers against them were suborned or not. The records leave a considerable degree of obscurity on the whole matter. All we can learn is, that a man named Squin de Flexian, who had been a Prior of the Templars, and had been expelled the Order for heresy and various vices, was lying in prison at Paris or Toulouse, it is uncertain which. In the prison with him was a Florentine named Noffo Dei, "a man," says Villani, "full of all iniquity." These two began to plan how they might extricate themselves from the confinement to which they seemed perpetually doomed. The example of the process against the memory of Pope Boniface, shewed them that no lie was too gross or absurd not to obtain ready credence, and they fixed on the Templars as the objects of their charges. Squin told the governor of the prison that he had a communication to make to the King, which would be of more value to him than if he had gained a kingdom, but that he would only tell it to the King in person. He was brought to Philip, who promised him his life, and he made his confession, on which the King immediately arrested some of the Templars, who are said to have confirmed the truth of Squin's assertions. Shortly afterwards, it is said, similar discoveries were made to the Pope by his chamberlain, Cardinal Cantilupo, who had been in connexion with the Templars from his eleventh year.

Squin Flexian declared, 1. That every member on admission into the Order swore on all occasions to defend its interests right or wrong; 2. That the heads of the Order were in secret confederacy with the Saracens, had more of Mahommedan unbelief than of Christian faith, as was proved by the mode of reception into the Order, when the novice was made to spit and trample on the crucifix, and blaspheme the faith of Christ; 3. That the superiors were sacrilegious, cruel, and heretical murderers; for if any novice, disgusted with its profligacy, wished to quit the Order, they secretly murdered him, and buried him by night; so, also, when women were pregnant by them, they taught them how to produce abortion, or secretly put the infants to death; 4. The Templars were addicted to the error of the Fraticelli, and, like them, despised the authority of the Pope and the Church; 5. That the superiors were addicted to the practice of horrible crimes, and if any one opposed them, they were condemned by the Master to perpetual imprisonment; 6. That their houses were the abode of every vice and iniquity; 7. That they endeavoured to put the Holy Land into the hands of the Saracens, whom they favoured more than the Christians. Three other articles of less importance completed this first body of charges. It is remarkable, that we do not find among them those which made such a figure in the subsequent examinations; namely, the devil appearing among them in the shape of a cat; their idolatrous worship of an image with one or three heads, or a skull covered with human skin, with carbuncles for eyes, before which they burned the bodies of their dead brethren, and then mingled the ashes with their drink, thereby thinking to gain more courage; and, finally, their smearing this idol with human fat.18

It was unfortunate for the Templars that their chapters were held in secret,19 and by night, for an opportunity was thereby afforded to their enemies of laying whatever secret enormities they pleased to their charge, to refute which, by the production of indifferent witnesses, was consequently out of their power. Philip having now all things prepared, sent, like his descendant Charles IX. previous to the St. Bartholomew massacre, secret orders to all his governors to arm themselves on the 12th of October, and on the following night, but not sooner, on pain of death, to open the king's letter, and act according to it. On Friday the 13th of October, all the Templars throughout France were simultaneously arrested at break of day. The unhappy Knights were thrown into cold cheerless dungeons, (for they were arrested, we should remember, at the commencement of winter), had barely the necessaries of life, were deprived of the habit of their Order, and of the rites and comforts of the church; were exposed to every species of torture then in use, were shown a real or pretended letter of the Grand Master, in which he confessed several of the charges, and exhorted them to do the same; and finally, were promised life and liberty, if they freely acknowledged the guilt of the Order. Can we then be surprised that the spirit of many a Knight was broken, that any hope of escape from misery was eagerly caught at, and that falsehoods, the most improbable, were declared to be true? And it is remarkable that the most improbable charges are those which were most frequently acknowledged, so just is the observation, that men will more readily in such circumstances acknowledge what is false than what is true; for the false they know can be afterwards refuted by its own absurdity, whereas truth is permanent.

Of the Templars in England 228 were examined;20 the Dominican, Carmelite, Minorite, and Augustinian friars brought abundance of hearsay evidence against them, but nothing of any importance was proved; in Castile and Leon it was the same; in Aragon the Knights bravely endured the torture, and maintained their innocence; in Germany all the lay witnesses testified in their favour; in Italy their enemies were more successful, as the influence of the Pope was there considerable, yet in Lombardy the Bishops acquitted the Knights. Charles of Anjou, the cousin of Philip, and the foe of the Templars, who had sided with Frederick against him, could not fail, it may be supposed, in getting some evidences of their guilt in Sicily, Naples, and Provence. It is not undeserving of attention, that one of these witnesses, who had been received into the Order in Catalonia, (where all who were examined had declared the innocence of the Order), said he had been received there in the usual impious and indecent manner, and mentioned the appearance and the worship of the cat in the chapter!! Such is the value of rack-extorted testimony! In fine, in every country out of the sphere of the immediate influence of Clement, Philip, and Charles, the general innocence of the Order was acknowledged. In Portugal they were preserved under the altered appellation of the Knights of Christ, – a change which was effected by the friendly policy of Prince Denys, who in 1218, secured for them the sanction of the successor of Clement.21

Throughout the entire process against the Templars, from October 1307 to May 1312, the most determined design of the King and his ministers to destroy the Order meets us at every step; Philip would have blood to justify robbery; several Templars had already expired on the rack, perished from the rigour of their imprisonment, or died by their own hands; but on the 12th May 1310, fifty-four Templars who had confessed, but afterwards retracted, were by his order committed to the flames, in Paris, as relapsed heretics. They endured with heroic constancy the most cruel tortures, asserting with their latest breath the innocence of the Order, though offered life if they would confess, and implored to do so by their friends and relatives. Similar executions took place in other towns. The Pope soon went heart and hand with Philip. In vain did the bishops assembled at Vienne propose to hear those members who came forward as the defenders of the Order. A Bull of the Pope was fulminated against the Order,22 and transferred its possessions to the Knights of St. John, who, however, had to pay such enormous fines to the King and Pope before they could enter on them, as almost ruined them; so that if Philip did not succeed to the utmost of his anticipations, he had little reason to complain of his share.23 The members of the society of the Templars were permitted to enter that of the Hospitallers, – a strange indulgence for those that had spitten on the cross, and practised horrible vices.

But the atrocious scene was yet to come which was to complete the ruin of the Templars, and satiate the vengeance of their enemies. Their Grand Master, Molay, and three other dignitaries of the Order, still survived: And, though they had made the most submissive acknowledgments to their unrelenting persecutors, yet the influence which they had over the minds of the vulgar, and their connection with many of the Princes of Europe, rendered them formidable and dangerous to their oppressors. By the exertion of that influence, they might restore union to their dismembered party, and inspire them with courage to revenge the murder of their companions;24 or, by adopting a more cautious method, they might repel, by uncontrovertible proofs, the charges for which they suffered; and, by interesting all men in their behalf, they might expose Philip to the attacks of his own subjects, and to the hatred and contempt of Europe. Aware of the dangers to which his character and person would be exposed by pardoning the surviving Templars, the French Monarch commanded the Grand Master and his Brethren to be led out to a scaffold, erected for the purpose, and there to confess before the public, the enormities of which their Order had been guilty, and the justice of the punishment which had been inflicted on their brethren. If they adhered to their former confession, a full pardon was promised to them; but if they should persist in maintaining their innocence, they were threatened with destruction on a pile of wood, which the executioners had erected in their view, to awe them into compliance. While the multitude were standing around in awful expectation, ready, from the words of the prisoners, to justify or condemn their King, the venerable Molay, with a cheerful and undaunted countenance, advanced, in chains, to the edge of the scaffold; and, with a firm and impressive tone, thus addressed the spectators. – "It is but just, that in this terrible day, and in the last moments of my life, I lay open the iniquity of falsehood, and make truth to triumph. I declare then, in the face of heaven and earth, and I confess, though to my eternal shame and confusion, that I have committed the greatest of crimes; but it has been only in acknowledging those that have been charged with so much virulence upon an Order, which truth obliges me to pronounce innocent. I made the first declaration they required of me, only to suspend the excessive tortures of the rack, and mollify those that made me endure them. I am sensible what torments they prepare for those that have courage to revoke such a confession. But the horrible sight which they present to my eyes, is not capable of making me confirm one lie by another. On a condition so infamous as that, I freely renounce life, which is already but too odious to me. For what would it avail me to prolong a few miserable days, when I must owe them only to the blackest of calumnies."25 In consequence of this manly revocation, the Grand Master and his companions were hurried into the flames, where they retained that contempt for death which they had exhibited on former occasions. This mournful scene extorted tears from the lowest of the vulgar.26 Four valiant Knights, whose charity and valour had procured them the gratitude and applause of mankind, suffering, without fear, the most cruel and ignominious death, was, indeed, a spectacle well calculated to excite emotions of pity in the hardest hearts. Humanity shudders at the recital of the horrid deed; and if the voice of impartial posterity has not, with one accord, pronounced the unqualified acquittal of the Templars, it has branded with the mark of eternal infamy the conduct of their accusers and judges.

CONTINUATION OF THE ORDER

CHAP. IV.

The Continuation of the Order

But the persecution of the Templars in the fourteenth century does not close the history of the Order; for, though the Knights were spoliated, the Order was not annihilated. In truth, the cavaliers were not guilty, – the brother hood was not suppressed, – and, startling as is the assertion, there has been a succession of Knights Templars from the twelfth century down even to these days; the chain of transmission is perfect in all its links. Jacques de Molay, the Grand Master at the time of the persecution, anticipating his own martyrdom, appointed as his successor, in power and dignity, Johannes Marcus Larmenius of Jerusalem, and from that time to the present there has been a regular and uninterrupted line of Grand Masters. The charter27

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

1

"The Greek Convent adjoins the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. From the terrace of this Convent, you see a spacious enclosure, in which grow two or three olive trees, a palm tree, and a few cypresses. The house of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem formerly occupied this deserted spot." – Chateaubriand.

2

At a subsequent period, the war-dress of the Knights Hospitallers was a scarlet tunic, or sopra vest, on which was embroidered the sacred emblem of the Order. In the Convent, they wore a black robe similarly adorned, with a cap of dignity. The knights were authorised to wear these dresses by a Bull of Pope Alexander IV, in 1259. The other insignia were, —First, A star which was worn on the left breast, in the form of a cross patée, having eight points, symbolical of the eight beatitudes and the eight languages, which composed the Order; Second, A badge formed of a white enamelled cross, having the angles charged with the supporters, or principal device, of the respective kingdom to which the language belonged. This, surmounted by an imperial Crown, was worn originally suspended from the neck by a gold chain, latterly by a black ribband; to these were added the sword, scarf, spurs, &c. As an armorial distinction, the knights were privileged to augment their family arms with a chief, gules, charged with a cross, argent; and exteriorly adorned the shield with the mantle, cap of dignity, banners, badge, and motto, Pro Fide. These insignia, however, were of more modern adoption. —Vide Hospitallaria.

3

The first introduction of the Knights Hospitallers into England took place, according to Tanner, in 1101. Soon after this, the Grand Priory of St. John, at Clerkenwell, London, was founded by the Lord Jordan Briset. In 1185 it was formally dedicated by the Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem. Matthew Paris mentions that, in 1237, there went from the Priory of Clerkenwell three hundred knights to the wars in the Holy Land. It was set on fire by the rebels under Wat Tyler in 1381, and burnt for seven days; and it was not finally repaired till one hundred and twenty-three years afterwards, when the Grand Prior Docwra completed its reconstruction. This building is said to have exhibited curious specimens of the Arts of Europe and Asia, and contained collections of books and other rarities. – (Cromwell's Hist. Parish Clerkenwell.)