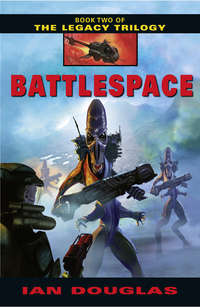

Battlespace

“Yeah. It just feels … odd. Where are we?”

“The Marine Corps Cybernetic Hibernation Receiving Facility,” the Marine with the board said. “Twentynine Palms.”

“Then I’m home.”

The other Marine laughed. “Don’t make any quick judgments, timer. You’ll null your prog.”

“Huh?”

“Just lie there for a minute, guy. Don’t sweat the net. If you gotta puke, puke on the deck. The auts’ll take care of it. When you feel ready, sit up … but slow, understand? Don’t push your body too hard just yet. You need time to vam all the hibenano out of your system. When you feel like moving, make your way to the shower, get clean, and rec yourself some utilities.”

Garroway was already sitting up, swinging his legs off the pallet. “I’ve done this before,” he said.

“Suit yourself,” the Marine said. They were already moving away, beginning to cycle open the next cybehibe capsule in line, a few meters away. As the hatch cycled open and the pallet extruded itself from the bulkhead, Garroway could see the slowly moving form of Corporal Womicki half-smothered in green nanogel.

“What’s your name, buddy?” one of the revival techs asked.

“Wo-Womicki, Timothy. Lance Corporal, serial number 15521-119—”

“He’s tracking.”

“Welcome to 2159, Marine.”

The routine continued.

Elsewhere around the circular, fluorescent-lit compartment, other Marine revival techs were working with men and women emerging from cybehibe, dozens in this one room alone. Some, nude and pasty-looking, were already standing or making their way toward a door marked showers, but most remained on their pallets.

“Hey, Gare!” Womicki’s voice was weak, but he was sitting up. “We made it, huh?”

“I guess we did.”

“Whatcha think the pool number is?”

His stomach gave an unpleasant twist. “Dunno. Guess we’ll find out.”

The deathwatch pool was a kind of lottery, with the Marines betting on how many would die in cybehibe passage.

How many of their buddies had made it?

And then his head started swimming and he vomited explosively onto the deck, emptying his stomach of yet more of the all-pervading foamy nanogel.

A long moment later, his stomach steadied, and he began working on bringing some focus to his muddled thinking.

Twentynine Palms. This was the place where he’d been loaded into cybe-hibe preparatory to being shuttled up to the IST Derna like a crate of supplies. That felt like a year ago or so … not twenty years.

Well, his various briefings had warned him that he’d have some adjusting to do. Between the effects of relativity and the cybehibe sleep, he’d been just a bit out of touch with the rest of the universe.

He thought-clicked his cerebral implant. “Link. Query. Local news update.”

He expected a cascade of thought-clickable headers to scroll past his mind’s eye, but instead a red flash warned him that his Net access had been interdicted. “All shoreside communications have been restricted,” the mental voice told him. “You will be informed when it is permissible to make calls off-base or receive information downloads.”

A small flat automaton of some sort was busily cleaning up the mess he’d made on the deck.

So far, he thought, this is a hell of a welcome home. …

Headquarters Star Marine Force Center Twentynine Palms, California 1750 hours, PST

“Why,” Colonel Thomas Jackson Ramsey said as he took a seat at the conference table, “all the extra security? My people have calls they want to make, and they’re justifiably curious about the Earth they’ve just come home to. But we appear to be under quarantine.”

“Quarantine is a good word for it, Colonel,” General Richard Foss told him. “Operating policy now calls for a gradual insertion of returning personnel into ordinary life. Things have changed a lot in twenty years, you know.”

“How much?”

“The political situation is … delicate.”

“It usually is. Damn it, what’s going on?”

“The European Union has recognized the independent nation of Aztlan, along with Mexico, Brazil, and Quebec. All U.S. military bases are on full alert. The borders are closed. War may be eminent.”

“Jesus.” Ramsey frowned. “An EU ship brought us home.”

“The crisis flared up for the first time a year ago, about the time you were beginning deceleration, a half light-year out. Geneva recognized Aztlan independence, at least in principle, and was offering to broker talks. There was … concern, in some circles, that you people might be held hostage if war did break out.”

Ramsey nodded. The Aztlan question had been smoldering for some years, even before the Derna had left for Ishtar, and it really was only a matter of time before there was a final showdown. The Aztlanistas wanted a homeland—to be carved out of the southwestern states of the Federal Republic of North America, land they claimed had been unjustly taken from Mexico in the wars of 1848 and 2042. Since that homeland would consist of some of the United Federal Republic’s choicest and most populous real estate—southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Baja, Sonora, Sinaloa, and Chihuahua—Washington flatly refused to negotiate.

Unfortunately, there were a number of players in the world arena, including China and the EU, who would like to see the UFR taken down a notch or three, and breaking away 8 of the Federal Republic’s 62 states would certainly accomplish that.

“Things were smoothed out,” General Foss continued. “Our AIs talked to their AIs, a summit conference was held at Pacifica, and things quieted down a bit.

“But two weeks ago, while you were still inbound out beyond the orbit of Saturn, Aztlanistas managed to smuggle a small AM bomb into the Federal Building in Sacramento. Twelve hundred dead—and the heart of the city leveled. At this point in time, Colonel, as you can imagine, there is considerable ill feeling toward people of Hispanic descent. Three days ago, anti-Latino rioting in New Chicago and in New York resulted in several hundred dead and over a thousand injured.”

“That still doesn’t explain why my people are being held incommunicado, sir.”

Foss didn’t reply for a long moment. His eyes seemed a bit unfocused and Ramsey waited. Possibly he was talking with someone else over his implant or downloading some key information.

“Colonel,” Foss said at last, “there are people in the current administration who were suggesting MIEU-1 shouldn’t be allowed back to Earth.”

“What?”

Foss held up a hand. “You were working with the EU on Ishtar,” Foss said. “And you pulled that cute stunt that pulled the rug out from under PanTerra. There are some who question your loyalty, Colonel, and the loyalty of the Marines under your command.”

Ramsey came to his feet. “Who?” he demanded.

“Take it easy, Colonel.”

“I will not take it easy. Sir. Who is accusing my men of disloyalty?”

“Sit down, Colonel!” As Ramsey grudgingly took his seat, Foss folded his hands on the table and continued. “You know how rumors spread, Colonel. And how poisonous they can be. They take on a life of their own, sometimes, and do some horrific damage.”

“That does not answer the question, General.” Ramsey was furious. “If I screwed up with the Ishtaran state, then court-martial me. But I was responsible, not my men!”

“No one is talking about courts-martial, Colonel. Not yet, at any rate. You did overstep your authority, true, but there were … extenuating circumstances.”

“Like the fact that my orders were coming from eight-point-three light-years away? And that something had to be done immediately?”

“Well, yes. More to the point, however, your mission required you to support the PanTerran representatives and their interests.”

“Which, it turned out, involved ‘liberating’ human slaves from the Ahannu, so they could be shipped to Earth as contract laborers. Slavery, in other words.”

“Not slavery, Colonel …”

“Oh? What are you calling it these days?”

“Liberational relocation.”

“Bullshit. Sir. The Sag-ura have been shaped by ten thousand years of Ahannu selective breeding and conditioning.” Sag-ura was the name for the descendents of humans removed from Earth thousands of years before and taken to other worlds of the Ahannu empire. “PanTerra was planning on shipping them in cybehibe tubes back to Earth to be trained and sold as ‘domestics.’ With no understanding of Earth–human culture, what chance would they have had for real freedom?”

“You made certain political decisions, Colonel.” He gave a grim, hard smile. “Do you realize that they’re calling it ‘Ramsey’s Peace’ now?”

“Yes, sir. We helped facilitate the creation of an independent Sag-uran state, which should be able to look out for the interests of humans living on Ishtar.”

“And it was not within the purview of the Marines to dabble in local politics.”

“No, sir. Except that the Ahannu had surrendered. Earth was eight-and-a-half light-years away, and the EU–Brazilian military expedition was due to show up in another five months. Do you think they would have tried to guarantee the safety of the Sag-ura?”

“Probably not. Especially since they have PanTerran connections as well.” Foss cleared his throat. “The point, Colonel, is that you did overstep yourself by making the decisions you did. But that’s not why I called you in here.”

Ramsey worked to control his anger. “Yes, sir.”

“There is widespread suspicion that MIEU-1 was working with the EU on Ishtar.”

“Reasonable enough. We were. Under orders.”

“Indeed. And by brokering that agreement with the natives and creating that sag-uran state, whatever it’s called …”

“Dumu-gir Kalam, sir.”

“Whatever. You did steal a march on the EU. They couldn’t very well abrogate treaties you’d written and signed, not without an incident and some very bad press back home.”

“So the Accord is holding up?”

“Has for the ten years since you left, Colonel, yes. As for the future? Who knows? The EU have established a diplomatic mission on Ishtar, now.”

“So they’re playing by the rules, at least.”

“For now. But my concern is what’s happening on this planet. On Earth. Specifically, we have people—both in the government and ordinary Joes and Janes on the streets—who think you were somehow collaborating with the EU on Ishtar. And they know that the EU brought you back to Earth on one of their transports.”

“Well, it was that or have us stay there with them.”

“It was decided to have MIEU-1 return to Earth, Colonel. Protecting UFR interests on Ishtar is the Army’s job now.” An Army occupational force consisting of elements of the First Extrasolar Special Operations Group had accompanied the EU and Brazilian joint expedition. “However, that has caused some serious problems for us here.”

“My men are loyal, General,” Ramsey said through clenched teeth. “You can’t lock them away without a fair hearing.”

Foss sighed. “Colonel, it’s not just the loyalty question. You should know that. The Ahannu are the focus of the biggest religious brouhaha since Adam and Eve got their eviction notice in Eden. Some people think they are gods—or the descendents of gods—and that our proper place is at their feet, worshipping them.”

“Crackpots.”

“Some think they’re demons and think it’s wrong to have any political dealings with them at all. Some think they’re the underdogs, poor, misunderstood little primitives, and the big, bad Marines are out to commit high-tech genocide. Some think they’re your stereotypical bug-eyed monsters lusting after human females, slave masters who must be punished. The Papessa is saying the Ahannu ought to be stopped from keeping slaves. The Anti-Pope is saying we have to treat the Ahannu as friends and equals and to respect their traditions. The list goes on and on.

“The point is, Colonel, you and your people have come back to Earth at a rather sensitive time. You can’t help but be caught up in the politics—and the religious controversy. You’ve just stepped off the boat, Colonel, and smack into quicksand.”

“If you’re looking for a scapegoat, General, you’re free to take a shot at me. I’ll fight it, but you can try. But it is a monstrous injustice to blame the men under my command for—”

“No one is blaming them, Colonel. Or you. But I needed to make sure you understood the … ah … delicate nature of your position here.”

“You’ve got my attention, sir. That’s for damned sure.”

“We have a new situation, one that calls for MIEU-1’s special, um, talents.”

“Another deployment, General?”

He nodded. “Another deployment.”

“To where?”

“To Sirius. Eight-point-six light-years out. The brightest star in Earth’s night sky.”

That pricked Ramsey’s interest. “The Wings of Isis, sir? She found something?”

“Link in, Colonel, and I’ll fill you in with what we know.”

Ramsey closed his eyes and felt the familiar inner shiver as data began to flow, downloading through his cereblink.

Visual: A wedding band adrift in space. Two stars, arc-brilliant and dazzling to look at, hung in the distance, suspended against wispy clouds of hazy light.

“These images were laser-transmitted to us as they were being made,” Foss said. “They arrived two years ago. The star on the left is Sirius A. The other is Sirius B, the white dwarf. And the Wheel. …”

Visual: The NetCam zooms in and the structure is revealed to be enormous. Data scrolls down one side of the visual, indicating dimensions and mass. The structure is titanic, twenty kilometers across, but massing as much as a small start. The density of the thing—better than 6 × 1018 grams per cubic centimeter—is astonishing.

“An alien artifact?”

Foss nodded.

“What is it? A space station? A space habitat of some kind?”

“No. At least … we don’t think so.”

“That density reading,” Ramsey said, examining the data. “That can’t be right.”

“According to gravitometric scans made by the Wings of Isis, it is,” Foss replied.

“Neutronium? Collapsed matter?”

“The density’s not that high. Most of that thing is actually hollow. But we think we know what’s going on. Think of that hoop as a kind of particle accelerator, like the hundred-kilometer supercollider at Mare Humorum on the moon.”

“Okay. …”

“Now imagine, instead of subatomic particles, what you have whirling around inside that giant racetrack are tiny black holes. And they’re moving at close to the speed of light.”

“Black holes? My God, why?”

“Best guess is that what we’re looking at here is an inside-out Tipler Machine.”

“A what?”

“Here’s the data.”

Frank Tipler had been a prominent physicist at the turn of the twenty-first century. Among other things, he’d suggested the mechanism for a means of bypassing space, of jumping from here to there without the tedious process of moving through the space in between. His scheme had called for building a very long cylinder, one hundred kilometers long, ten kilometers wide, and made of neutronium—the ultra-dense collapsed matter of a neutron star. Rotate the thing two thousand times a second, so the surface is moving at half the speed of light. Theoretically, according to Tipler, the rotating mass would drag space and time with it, opening paths through both above the surface. By following a carefully plotted course around the rotating cylinder, a starship pilot could cross light-years in an instant … and would be able to fly back and forth through time as well.

The whole thing was just a thought experiment, of course. No one seriously expected anyone to ever be able to squash neutron stars together in order to make their own time machine.

But someone, evidently, had figured out another way to do the same thing.

“So that thing’s a time machine?” Ramsey asked after he’d had a moment to digest the download.

“Space and time,” Foss replied. “Space-time equivalence, remember? We think this must be one of several identical gateways, constructed around different stars. You fly into one and come out another. We don’t know if they use the time travel component at all, though the smart money says they don’t. They would screw causality to hell and gone if they did. Now. Watch. …”

Visual: The stargate appears from a different angle, suspended against the background haze of the Sirian system. Something appears in the middle, a little off-center. One moment there is nothing there; the next, there is something, a golden object rendered tiny by the scale of the vast Wheel. The scene magnifies, zooming in for a closer look. The object appears to be a ship of some sort, needle slender, but somewhat swollen aft, golden-hued. Data readouts show the object to be over two kilometers long.

Ramsey felt his scalp prickle as he watched the ship grow rapidly larger. The vessel appeared to accelerate suddenly, leaping toward him. …

The image cut off in a burst of white noise and electronic snow.

He blinked. “Okay,” he said slowly. “We have first contact with a high-tech civilization. Who are they?”

“That,” Foss replied, “we don’t know.”

“What happened to the Wings of Isis?” The words were hard, grim.

“We don’t know that, either. Whatever happened, of course, happened ten years ago, while you were still on Ishtar. We have to assume that the Wings of Isis was destroyed, since two more years passed after these images were recorded and transmitted, and we’ve heard nothing from them. That might have been an accident or …”

“Or enemy action. The Hunters of the Dawn?” Ramsey’s heart was beating a little faster now and he felt cold.

“Again, Colonel. We don’t know. But we hope you and your people will be able to tell us.”

“Huh. You don’t believe in easy assignments, do you, sir?”

“This is the Marine Corps, son,” Foss told him. “The only easy mission was the last one.”

2

27 OCTOBER 2159

Marine Receiving Barracks Star Marine Force Center Twentynine Palms, California 1825 hours, PST

“So what’s the dope, Gare?” Lance Corporal Roger Eagleton asked. “You hear anything?”

“Nope,” Garroway said around a mouthful of steak-and-cheese. “You think they tell me anything?”

“You’re the one with the famous Marine ancestor,” Kat Vinton told him.

“I guess. So why would that mean they’d tell me what’s going on?”

“I don’t know. With your name, we figured they were grooming you for a recruiting tour, y’know?”

“Yeah,” Corporal Bill Bryan added. “Just to keep you happy, so’s you can be convincing with your sales pitch. You know. ‘Join the UFR/US Marines! Travel to exotic climes! Explore strange new cultures! Meet fascinating people! Kill them.’”

“Ooh-rah.”

They were seated at a long mess table, showered, dressed in newly issued utilities, and packing in their first meal in ten years. The chow was first-class and there was lots of it, but now that their stomachs had gotten rid of the last of that damned packing gel and had some time to settle, they were hungry. Even three-lies-in-one field rations would have seemed like food of the gods under the circumstances.

“How about you, Sarge?” Kat asked the big man at the end of the table. Staff Sergeant Richard “Well” Dunne was acting platoon sergeant now and the platoon’s liaison with all higher authority. “They tell you what’s going on?”

“Negative,” Dunne said. “The word is to sit tight and all will be revealed.”

“Hurry up and wait,” Garroway said. “The litany of the modern Marine Corps.”

“Fuck that shit,” Sergeant Wes Houston said. “It’s been that way since Sargon the Great was a PFC.”

Garroway continued to eat, but he was somewhat unsettled. Kat’s crack about his famous ancestor had caught him by surprise. His great-grandfather had been Sands of Mars Garroway, a tough old-Corps Marine who’d led his men on a grueling march through the Vallis Marineris during the U.N. War of 2042 to capture an enemy-held base. The man was one of the legends of the Corps, another live-forever name like Dan Daily, Smedley Butler, and Chesty Puller. When he’d gone through his Naming Ceremony, he’d deliberately chosen his mother’s maiden name—Garroway—hoping, perhaps, that some of the luster of that name would rub off on him.

Now that he was a Marine himself, though, he frequently found himself wishing it wouldn’t rub off quite so much. Officers and NCOs tended to expect more from him than of others, and everyone else assumed the name meant he had things easy.

The fact was that there was no favoritism in the Corps—not below the rank of colonel, at any rate, not that he’d been able to detect.

“There’s one piece of good news,” Dunne said. “The TIG promos are probably gonna go through. That’s something, at least.”

Appreciative claps, whistles, and cheers sounded from around the mess table. It was good news.

In the service, being promoted from one rank to the next required passing advancement tests, but more it required TIG—time-in-grade. Garroway had boarded the Derna right out of boot camp as a wet-behind-the-ears private first-class, pay grade E-2. The voyage out to Lalande 21185 had taken ten years, objective time, though relativistic effects contracted that to four years, ship’s time.

His promotion to E-3, lance corporal, had been pretty much automatic. Technically, he’d needed six months as an E-2 and four years subjective counted, even if he’d slept through most of it in cybehibe. He’d received his chevron above crossed rifles while serving on Ishtar.

He’d been on Ishtar for less than a year, however, before being packed onboard the Jules Verne and popped back into cybehibe for the return voyage. The promotion to the next rank, corporal, required a year in-grade plus a test. He would be an NCO, a noncommissioned officer, at E-4, with more responsibility and higher expectations regarding his performance.

So here he was … ten years objective and four years subjective later. Technically, he had the time in grade. What he did not have was the experience.

Still, it was embarrassing to be a Marine with—according to his Earthside records—twenty-one years in, and he was only an E-3. If he’d not gone to the stars, if he’d stayed in and stayed out of trouble, he would be a goddamned sergeant major by now, at the exalted pay grade of E-9.

Scuttlebutt had it that the brass was considering a blanket set of promotions for the men and women of Operation Spirit of Humankind, with everyone bumped up a pay grade and given a hefty out-system combat bonus to boot. There was talk of a special download training session to implant the necessary skills and knowledge that went with the rank.

Of course, if they kept that up, they’d have a whole platoon of gunnery sergeants. He wondered how they would handle the tendency for units to go top-heavy like that.

“There’s also some other news,” Sergeant Dunne went on, “though I can’t vouch for it. Word is they may be about to offer us another deployment.”

That brought shocked silence to the table. “Another deployment?” Kat asked. “Where?”

Dunne shrugged. “I was talking to the senior revival tech a while ago. All he knew was that we were being kept here for a while, possibly with the idea of letting us volunteer to go out-system again.”