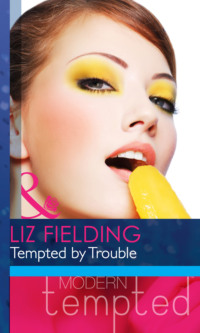

Tempted by Trouble

Sorrel had presumably walked her grandmother to church before going on to take advantage of the free Wi-Fi at the Blue Boar. And Geli would be doing an early turn, dog walking at the animal sanctuary.

She dropped the envelope and van keys she’d retrieved from the hall drawer onto the kitchen table, then opened the back door.

The sun poured in, bringing with it the song of a blackbird, the scent of the lilac and she lifted her face to the sun, feeling the life seep back as she breathed in the day. Breathed out the unpleasantness of last night. That girl with Sean McElroy might have been beautiful, elegant and polished, but beauty is as beauty does, at least that was what her grandmother always said.

She suspected that beauty like that could, and did, do whatever it pleased and Sean McElroy was clearly happy to let her.

Freddy had moved her to another table after the incident with the rolls. He had been quick to reassure her that he didn’t blame her for what happened but, after all, the customer was always right.

It should have been a relief. Was a relief, she told herself. Between Sean and his girlfriend, someone would undoubtedly have had their dinner in their lap.

She had enough on her plate sorting out Rosie, without that kind of trouble. But not before she’d had a cup of tea and got some solid carbs inside her, she decided, picking up an elastic band from the bowl on the dresser and fastening back her hair.

She opened the bread bin.

Nothing but crumbs. And a shake told her that the cereal box on the table was empty.

She was on her knees hunting through the cupboards for the packet she’d bought the day before when a shadow cut off the sunlight.

It was too soon for her grandmother or Sorrel and she looked up expecting to see Geli, ready for a second helping of breakfast before going into Maybridge with her friends. And out of luck because the empty box on the table was the one she’d bought the day before.

But it wasn’t Geli.

The silhouette blocking out the light was that of Pink Van Man himself, but only momentarily, since he didn’t wait for an invitation but walked right in before she could ask him what the heck he thought he was doing.

A fast learner.

CHAPTER THREE

Life is uncertain. Eat dessert first.

—Rosie’s Diary

SEAN MCELROY looked so much bigger, so much more dangerous now that she was on her knees. Maybe he was aware of that because he bent to offer her a hand up, enveloping her in a waft of something masculine that completely obliterated the scent of the lilac.

Old leather, motor oil, the kind of scents unknown in an all female household, and she found herself sucking it in like a starving kitten.

Her eyes were level with a pair of narrow hips, powerful thighs encased in soft denim, closer to a man—at least one she wanted to be close to—than she’d been since she’d said goodbye to her dreams and taken a job working unsocial hours.

‘How did you get in?’ she demanded.

‘The gate was open.’

Oh, great. She nagged about security but no one took her seriously. Except, of course, it wasn’t about that.

Leaving the gate open was Geli’s silent protest against Elle’s flat refusal to take in any more four-footed friends, no matter how appealing. Why bother to shut the gate when there was no dog to keep off the road?

She shook him off, cross, hot and bothered. ‘It’s not an invitation for anyone to walk in,’ she snapped, standing up without assistance.

‘No? Just as well I closed it then,’ he said. ‘It could do with a new lock.’

‘I could do with any number of new things, Mr McElroy. The one thing I don’t need is an old van. Can I hope that your arrival means you’ve realised your mistake and have come to take her home?’

‘Sorry,’ he said.

‘You don’t look it.’ He wasn’t smiling exactly, but she was finding it hard to hold onto her irritation.

‘Would it help if I said that I honestly believed you were expecting her?’

‘Really?’ she enquired. ‘And what part of “Go away and take Rosie with you” didn’t you understand?’

He ignored the sarcasm. ‘I thought that once you’d opened the envelope it would make sense.’

‘So why are you here now?’

He shrugged. ‘I’m not sure. Just a feeling that something’s not quite right. Did Basil leave a note?’ he asked, nodding in the direction of the envelope. ‘I’m a bit concerned about him.’

‘But not about me, obviously. Your little stunt last night could have cost me my job. Did you enjoy your salmon?’ she accused.

‘I have to admit that the evening went downhill right after you dumped a basket of hot rolls in my lap,’ he said.

‘I hope you’re not expecting an apology.’

‘No. I take it you didn’t get the message I left for you?’

He’d left a message? She shook her head. ‘We were rushed off our feet last night. I didn’t hang around to chat.’

‘No?’ There was something slightly off about the way he said that.

‘Would you?’ she asked. ‘After six hours on your feet?’

‘It depends what was on offer.’

She frowned and he shook his head. ‘No, forget it. I’m sorry if you got into trouble but you have to admit that while you might not know Basil, the name Bernard certainly makes you all jump.’

‘All?’

‘Your grandmother nearly passed out when I asked her if she’d had Basil’s letter,’ he explained.

‘Gran? Are you telling me that you came back here yesterday? After I’d gone to work?’

‘I called in on my way to the Blue Boar. I did tell the skinny vampire that I’d come back this morning,’ he said.

‘Geli …’ She smothered a grin. ‘I haven’t seen her this morning. I’ve only just got up. What did Gran say?’

‘She wasn’t exactly coherent, but I think the gist was that Bernard wouldn’t allow her to receive a letter from Basil. She seemed panic-stricken at the thought.’

‘Well, that’s just ridiculous. Bernard was my grandfather but he’s been dead for years,’ she told him.

And yet there was obviously something. It was there in the letter.

‘Tell me about him,’ she said.

‘Basil?’ He shrugged. ‘I don’t know much. He’s just an old guy with two passions in his life. Rosie and poker.’

‘He’s a gambler? Are you saying that he puts Rosie up as surety for his bets?’

‘He’d never risk losing Rosie,’ he assured her. Then added, ‘Which is not to say that if he got into trouble some of his playing partners wouldn’t take her in lieu if they could get their hands on her.’

‘So, what are you saying? That you’ve been appointed getaway driver and I’ve been chosen to give her sanctuary?’ It … not she. She was doing it now. But it explained why Basil had gone to the bother of registering her grandmother as Rosie’s keeper.

‘That’s about the gist of it,’ he admitted, stretching his neck, easing his shoulders.

‘Don’t do that!’ she said as his navy polo shirt rippled, offering a tantalising promise of the power beneath the soft jersey. Talk about distraction …

Sean frowned. He didn’t have a clue what she was talking about, thank goodness.

‘Does he disappear regularly?’ she asked before he had time to work it out.

‘I wouldn’t know. I’m his landlord, not his best buddy. But he garages Rosie with me and I was in London when he took off and he couldn’t get in. It would seem that his need to disappear was too urgent to wait until morning.’

‘So, what? He dropped a note through your letter box asking you to bring her here?’

‘I’m sorry about that,’ he said, looking slightly uncomfortable, no doubt thinking that she was taking a dig at him for doing the same. ‘I assumed that once you’d read whatever was in the envelope you’d know what to do.’

What to do?

It got worse, she thought, suddenly realising exactly what this was all about.

‘I’m sorry, Sean, but if you’ve come here expecting to be paid your rent, you’re out of luck. I don’t know Basil Amery and, even if I did, I couldn’t help you. You’re going to have to sell Rosie to recover your losses.’

‘Sell Rosie? Are you kidding?’

‘Obviously,’ Elle said, back to sarcasm. ‘Since she’s Basil’s pride and joy.’

‘You don’t sound convinced.’

‘I can think of more important things to lavish your love on. I mean, how would you react to someone you’ve never heard of expecting you to run an ice cream round for him?’

Sean thought about it for a moment, then said, ‘Why don’t I put the kettle on? I make a mean cup of coffee.’

‘I haven’t got any coffee,’ she said, tucking a wayward strand of hair behind her ear.

‘Tea, then,’ he said, picking up the kettle, filling it and turning it on. He took a couple of mugs off the dresser and since the tea bags were stored in a tin with ‘TEA’ on the front—life was complicated enough without adding to the confusion—he found them without making a mountain out of a molehill. So far, he was doing better than either of her sisters ever managed. ‘Milk, sugar?’ he asked, dropping a bag in each mug.

She wanted to tell him to go and take the van with him, but he was right. They needed to get to the bottom of this.

‘Just a dash of milk.’

Was there any milk?

‘How about sugar? You’ve obviously had a shock.’

‘Of course I haven’t,’ she said, pulling herself together. ‘This is some kind of weird mistake. It has to be.’

They weren’t the most conventional family in the world, but they didn’t have secrets. Quite the contrary. Anyone would give him chapter and verse …

He glanced back to her.

‘What are you so scared of, Elle?’

‘I’m not scared!’

‘No?’

‘No!’ She’d faced the worst that the world could throw at her, but he was right, something about this put her on edge and, seizing on the fact that the kettle hadn’t come on to divert his attention, she said, ‘You have to give the plug a wiggle.’

He wasn’t diverted, just confused, and she reached behind him.

‘Don’t!’ Sean said as he realised what she was doing. He made a lunge in her direction, but not in time to stop her. There was a bit of a crackle and a tiny shock rippled up her arm, then the light came on and the kettle began to heat up noisily.

Her cheeks lit up to match but the rush of heat that invaded her body, starting at the spot where his hand was fastened over hers was, fortunately, silent.

Or maybe not.

Maybe the hammering of her pulse in her ears was so loud that Sean could hear it too, because he dropped her hand so fast that you’d have thought she was the one with dodgy wiring.

Without a word, he took a wooden spoon from the pot by the stove, used the handle to switch off the kettle and then removed the plug from the socket.

Whatever. Tea had been his idea.

But he wasn’t done. Having disconnected the kettle, he began opening the dresser drawers.

‘Excuse me!’

He held up a screwdriver he’d found in the drawer that contained bits of string, paper bags, the stuff that didn’t have any other home.

‘It’s beyond help,’ she told him. ‘It’s just …’ worn out, past its use by date, just plain old ‘… vintage. Like Rosie.’

‘It’s nothing like Rosie,’ he said, ignoring her protest as he set about taking the plug apart. ‘Rosie is not an accident waiting to happen.’

‘That’s a matter of opinion,’ she retorted.

‘No. It’s a matter of fact. She’s completely roadworthy or I wouldn’t be driving her.’ He looked up. ‘And I wouldn’t have brought her to you.’

‘No?’ Then, realising just how rude she was being, she blushed. ‘No, of course not. Sorry …’

‘No problem.’

‘I’m glad you think so,’ she said, only too aware of the envelope that was lying on the kitchen table with all the appeal of an unexploded bomb.

The Amery family had lived at Gable End for generations. This was the house Grandpa had been born in and it was marked with traces of everyone who’d ever lived there.

Their names were written in the fly-leaves of books that filled shelves in almost every room. Were scratched into the handles of ancient tennis racquets, stencilled onto the lids of old school trunks in the attic.

Their faces as babies, children, brides and grooms, soldiers, parents, grandparents, filled photograph albums.

There was no Basil.

Okay, there were gaps. Photographs fell out, were borrowed, lost.

Or had some been removed?

Gran had recognised the name. According to Sean, she hadn’t acted in the slightly silly, coy way she did when some man from the pensioners’ club chatted her up, and they often did because she was still beautiful.

She’d nearly passed out, he’d said. Panicked. And then there was Basil’s letter. He’d mentioned Bernard and referred to him as ‘my brother'. The connection was definitely there. Maybe she just didn’t want to believe it.

Taking a deep breath, she picked up the envelope—no one called her a scaredy-cat—and tipped the contents out onto the table so that he could see that she wasn’t trying to hide anything.

‘Here’s Basil’s letter,’ she said, offering it to Sean, who was leaning against the dresser, still poking about in the plug with the screwdriver. ‘You’d better read it,’ she said, thrusting it at him before turning her attention to the notebook.

On the first page, where a printed note said ‘In case of loss, please return to:’ the word ‘ROSIE’ had been written in block capitals, along with a mobile phone number. Presumably belonging to the phone on the table.

It was a page-a-day diary, she discovered, as she riffled through the pages, hoping for some clue. To the man. To his whereabouts.

There were appointments with names and telephone numbers by them. The occasional comment. Quotes by the famous, as well as Basil’s own wry or funny comments on the joys of ice cream. There were only a couple of recent entries.

‘He’s written “RSG” on yesterday’s date. Underlined. Do you know anyone with those initials?’

He thought about it for a moment, then shook his head.

‘That’s it, apart from “Service, Sean” written in the space for last Friday. Are you a mechanic? There’s a collection of vintage cars at Haughton Manor, isn’t there? Do you take care of them?’

‘They come under my care,’ he said. ‘Basil asked if I’d change Rosie’s oil, run a few basic checks to make sure everything was in good shape since he had some bookings. His back has been playing him up,’ he added, almost defensively. Doing little jobs on the side that his boss didn’t know about? Not her concern.

‘How much does he pay you?’ she asked. The last thing she needed was an elderly—vintage—vehicle that required high level, high cost maintenance, but she didn’t appear to have much choice in the matter. The mystery remained, but the connection between Basil and her family appeared to be proved.

He shrugged and a smile teased at the corner of his mouth, creating a tiny ripple of excitement that swept through her, overriding her irritation, and it occurred to her that a man like Sean McElroy could be seriously good for her state of mind.

‘Basil prefers to give payment in kind,’ he said.

‘Ice cream?’ She looked at him. The narrow hips, ropey arms. Her state of mind and all points south. ‘How much ice cream can one man eat?’

‘Fortunately, I don’t have to eat it all myself. He brought Rosie along to a family birthday party fully loaded with ice cream and toppings. The brownie points I earned for that were worth their weight in brake liners.’

‘Family? You have children?’

‘No. The party was for my niece. Half-niece.’ He shrugged. ‘I have a complicated family.’

‘Don’t we all,’ she said wryly. ‘But that’s a lot of ice cream for one little girl’s birthday.’

‘It was a big party. My family don’t do things by halves,’ he said.

‘No?’ They had that in common, only in her case it tended to be dramas rather than celebrations. ‘How do you know him?’

‘Basil? He’s a tenant on the Haughton Manor estate.’

‘Keeper’s Cottage. It’s on the vehicle logbook,’ she said. ‘It’s so near. I went there once on a school trip when we were doing the Tudors. It’s beautiful.’

‘So people keep telling me.’

‘You live there too?’ she asked.

‘Live there, work there, for my sins. Or, rather, my mother’s,’ he said, before returning to the letter. ‘Lally? Is that what people call your grandmother?’

‘Yes.’ She’d much rather hear about his mother’s sins, but he’d changed the subject so emphatically that she didn’t pursue it. ‘I doubt many people know her real name.’

‘Or yours?’

‘Or mine,’ she admitted.

‘Well, Basil certainly does, and he’s got a photograph of her on his mantelpiece to prove it.’

‘You’re kidding! A picture of my grandmother?’

He took a phone from his pocket, clicked through it and held it out to her. ‘I took this yesterday when I let myself in. Just to be sure that he hadn’t done anything … foolish.’

‘Killed himself, you mean?’ she said pointedly.

He didn’t answer but that was what he’d meant. It was why he was here now. Why he’d wanted to see the letter.

‘You have his keys?’ she asked.

‘Not personally. There are master keys in the estate safe. For emergencies.’

‘Or when a tenant does a runner,’ she said, taking the phone from him.

‘It is her?’ he asked about the woman in the photo.

She nodded. ‘It was taken in the late sixties, before she married my grandfather.’

Her grandmother had been the height of fashion with her dark hair cut in a sharp chin-length bob by a top London stylist, her huge eyes heavily made-up, her lips pale. And the dress she was wearing was an iconic Courrèges original design.

She handed it back to him. ‘How did you know this was gran?’

‘I didn’t until I saw her last night, but it was obvious she was related to you. The likeness is unmistakable.’

‘But she was …’

She stopped. Her grandmother had been the pampered daughter of the younger son of the Earl of Melchester. A debutante. An acknowledged beauty.

One of the girls in pearls who’d featured in the pages of Country Life.

While the Amerys were a solid middle-class family, it hadn’t been the marriage her father had planned for his daughter. No minor aristocracy to offer inherited wealth, park gates, maybe a title, so Elle’s grandmother had been pretty much cut adrift from her family when she’d married Bernard Amery.

‘I don’t look a bit like her,’ she said instead.

‘Not superficially, maybe, but you have her mouth. Her eyes. Basil recognised you,’ he pointed out. He looked again at the letter. ‘Is your grandmother about?’ he asked.

‘No!’ She shook her head. ‘You can’t bother her with this, Sean.’

‘You haven’t shown her the letter?’

‘Not yet.’ Once her grandmother had read it, Elle would be well and truly lumbered. And not just with an old crock that would cost a fortune to tax, insure, keep running. There were the obligations, too.

Oh, no, wait.

The connection had been made. He knew he’d brought Rosie to the right place and as far as Sean McElroy was concerned there was nothing more to be said.

She was already lumbered.

It was true, nothing good ever came out of a brown envelope. Well, this time it wasn’t going to happen. She wasn’t going to let it.

Whatever her grandmother had done for him in the past, Basil was going to have to sort out his own problems. They had quite enough of their own.

‘They seem to have been very close,’ he said, looking again at the letter. ‘He says she saved his life.’

‘He’d have had a job to end it all in the village pond,’ she told him dryly. ‘No matter what time of day or night, someone would be sure to spot you.’

‘Your grandmother, in this case. No doubt it was just a cry for help, but she seems to have listened. Sorted him out.’

Her ditzy, scatterbrained grandmother?

‘If that’s the case, why haven’t they seen one another for forty years? Unless …’ She looked up. ‘If she married his brother, maybe they fell out over her. She was very beautiful.’

‘Yes …’

‘Although why would Grandpa have removed every trace of his brother’s presence from the family home? After all, he got the girl,’ she mused.

‘Of course he got the girl. Basil is gay, Elle.’

‘Gay?’ she repeated blankly.

‘Could that be the reason his family disowned him?’ Sean asked.

‘No!’ It was too horrible to imagine. ‘They wouldn’t.’

‘People do. Even now.’

‘They weren’t like that,’ she protested.

Were they?

Sean was right. Forty years was a lifetime ago. She had no idea how her great-grandparents would have reacted to the news that one of their sons was gay. Or maybe she did. Basil had mentioned his mother in the letter. If she’d still been alive, he’d said …

You could change the law but attitudes took longer, especially among the older generation.

As for her grandfather, Bernard, he’d been a slightly scary stranger, someone who’d arrived out of the blue every six months or so, who everyone had to tiptoe around. Breathing a collective sigh of relief when he disappeared overseas to do whatever he did in Africa and the Middle East.

‘Whatever happened, Gran can’t be bothered with this. She’s not strong, Sean.’

As always, it was down to her. And the first thing she’d have to do was go through the diary and cancel whatever arrangements Basil had made. If she could work out what they were.

‘What does this mean?’ she asked, flicking through the notebook again.

Sean didn’t answer and she looked up, then wished she hadn’t because he was looking straight at her and those blue eyes made her a little giddy. She wanted to smile, grab him and dance. Climb aboard Rosie and ring her bell.

She took a deep breath to steady herself.

‘It says “Sylvie. PRC” Next Saturday'?’ she prompted, forcing herself to look away.

‘PRC? That’ll be the Pink Ribbon Club. It’s a charity supporting cancer patients and—’ He paused as he tightened the final screw in the plug.

‘And their families,’ she finished for him, the words catching in her throat. ‘I know.’

‘It’s their annual garden party on Saturday. They’re holding it at Tom and Sylvie MacFarlane’s place this year.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Longbourne Court.’

‘Oh, yes, of course. I’d heard it was occupied at last.’

‘I saw the signs advertising the garden party when I passed the gates. Basil mentioned it when he asked me to change Rosie’s oil. I got the feeling he’d volunteered to help because it meant something special to him.’

‘He should have thought of that before he bet the farm on the turn of a card,’ she said, suddenly angry with this man who appeared to have absolutely no sense of responsibility. Worse. Didn’t have the courage to face them and ask for help, but left someone else to do his dirty work. ‘But then, from his letter, he appears to have made a life’s work of letting people down.’

‘You’re assuming that it’s a gambling problem.’

‘You were the one who mentioned it as a possibility,’ she reminded him.

‘Grasping at straws? Maybe that was the problem with his family,’ he suggested. ‘Maybe he’d flogged the family silver to pay his creditors.’

‘Not guilty,’ she said, earning herself a sharp look. ‘And I thought you said it was a recent problem?’

‘He’s been living on the estate for less than a year, so what do I know? Maybe he only gambles when he’s unhappy. A form of self-harming?’

No, no, no … She wasn’t listening.

‘I can’t have Gran involved in anything like this, Sean.’

‘All he’s asking is that she—or, rather, you—keeps Rosie’s business ticking over.’

‘Is it?’

‘That’s what he put in the note he left me.’ He looked again at the letter to her grandmother. ‘This does make it sound rather more permanent, I have to admit.’