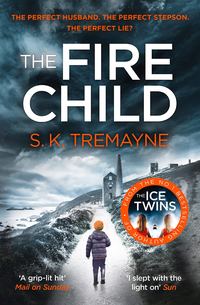

The Fire Child: The 2017 gripping psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The Ice Twins

Lingering by the bookshelves, I strain to think of a subject that might engage my stepson, but before I do, Jamie speaks.

‘Why?’

But he isn’t speaking to me. He is staring at the large painting on the wall opposite the sofa. It is a huge abstract, a column of horizontal slabs, of hazy, throbbing colour, blue over black over green.

I don’t especially like this painting; it’s the only one of Nina’s purchases of which I disapprove. The colours are beautiful and I’ve no doubt the painting cost thousands – but the colours are evidently meant to represent the coast, here, at Morvellan: the green fields, the blue sky, the black mine houses between. It has a dominant and foreboding quality. One day I will move it. This is my home now.

Jamie is still staring, rigidly, at the painting. Then again he says, to himself, as if I am not in the room, ‘Why?’

I step closer. ‘Jamie, why what?’

He doesn’t turn my way. He keeps talking into nothing. ‘Why? Why did you do that?’

Is he lost in some deep daydream? Something like sleepwalking? He looks perfectly conscious. Alert even. But intently focused on something I cannot perceive.

‘Ah. Ah. Why. There will be lights in the Old Hall,’ he says. Then he nods as if someone or something has answered his question, and then he looks at me – not directly at me, but slightly to my right – and he smiles: a flash of surprised happiness. He smiles as if there is someone nice standing next to me, and then he goes back to his book. Reflexively, I snap my head right, to find the person who makes Jamie smile.

I am staring at the wall. At empty space.

Of course there’s no one there. It’s only me and him. So why did I turn my head?

Part of me, abruptly, wants to flee. To run away. To get in my car and drive as fast as possible to London. But this is ridiculous. I am merely spooked. The hare, and now this. It is unbalancing. I’m not going to be scared by an eight-year-old boy, a soulful stepson with traumas. If I leave the Drawing Room now I will be admitting defeat.

I must stay. And if we cannot talk we can at least sit in companionable silence. That would be something. I can read in here, as he is reading. Let stepson and stepmother read together.

Crossing to the bookcase on the further side of the Drawing Room, I check the shelves. Jamie turns the pages of his book, his back to me. I can hear him flick the pages, quickly quickly.

There is a section here of Nina’s books that I have not read: tall, authoritative books on historical furniture, silverware, embroideries.

I pull out one book, The Care and Repair of Antique Furniture, flick through it and replace it, not sure what information I am seeking. Then I try another: Regency Interiors: a Guidebook. Finally, I choose a third: The Victoria and Albert Catalogue of English Woodwork, Volume IV. But when I pull the book from the shelf, something very different comes with it, flapping to the floor.

A magazine.

It looks like a gossip magazine. Why would it be kept here? Amongst Nina’s books?

Jamie is still deep in his reading. His capacity for quiet concentration impresses me. He gets it from his father.

Sitting down in one of Nina’s beautifully reupholstered armchairs, I scan the cover of the magazine and my question is answered. The magazine is dated from eight years ago, and right there, at the very top, is a small box. With a photo of a glamorous couple. David and Nina.

My heartbeat quickens. I read the caption.

Nina Kerthen, eldest daughter of French banker, Sacha Valéry, proudly shows her new baby, with her husband, Cornish landowner, David Kerthen.

We take a look inside their historic home.

Briskly I flick through the pages. Find the relevant section.

The article’s prose is silly celebrity journalese, venerating David and Nina for simply being rich and good-looking, aristocratic and lucky. The word ‘elegant’ is employed in almost every paragraph. It is froth and nonsense.

So why did Nina keep it? She was highly intelligent: she wouldn’t usually read this stuff. My guess is that she kept it for the photos, which are good. The magazine got a proper professional to do the job. There are some night-time exteriors of Carnhallow, showing the house glowing in the dark nocturnal woods like a golden reliquary in a shadowy crypt.

The photos of David and Nina are also impressive. And one, in particular, compels. I pause as I look at it, biting my own hair, thinking, reflecting.

This photo shows Nina, in a summer dress, sitting in a satin armchair, in this very room – the Yellow Drawing Room – with angled knees pressed together. And in this one singular picture she is holding baby Jamie. This is the only photo where we see their son, despite the promise of the magazine cover.

At her side, David stands tall, slim, and dark, in a charcoal black suit, with a protective arm poised around his wife’s bare, suntanned shoulder.

The photo is mysteriously perfect. I feel a sudden and powerful twinge of jealousy. Nina’s shoulder is so beautiful and flawless. She is so immaculate, yet decorously sensuous. Suppressing my envy, I scrutinize the rest of the image. The baby is, for some reason, barely visible. You can only just tell that it is Jamie, lying in his mother’s suntanned arms. But you can very clearly see a tiny fist, reaching from white swaddling.

If my heartbeat was quickened before, now it beats faster still. Because I am getting the sense I am staring at a clue, maybe even a distressing or important clue. But a clue to what? Why should there be a clue at all? I have to fight down my bewilderment. Regain my rationality. There is no mystery, there is no reason for me to be frightened or jealous. Everything is explained. Jamie is getting better, albeit slowly. We had a good summer. I will get pregnant. I will make friends. We will be happy. The dead hare was a coincidence.

‘What’s that you’re reading?’

Jamie is standing beside me. I didn’t hear him move.

‘Oh,’ I say, with a flash of startled embarrassment, quickly shoving the magazine between two books. ‘Only a magazine. Nothing important. Have you finished with your book? Do you want something to eat?’

He looks unhappy. Did he see the magazine in my hands? See his mother? It was daft and wrong of me to read it in here, in front of him, the grieving child. I won’t do that again.

‘Tell you what, I’ll warm up some of that lasagne, from yesterday, remember? You said you liked it.’

He shrugs. I babble on, eager to make the most of this conversation, however staccato. I can make us all a family.

‘Then we can talk, talk properly. How about a holiday next year? Would you like that? We’ve had such a nice summer here, but maybe next year we could go abroad, somewhere like France?’

Now I pause.

Jamie is frowning intensely.

‘What’s wrong, Jamie?’

He stands there, black and white in his school uniform, looking at me, and I can see the deep emotion in his eyes, showing sadness, or worse.

And then he says, ‘Actually, Rachel, you should know something.’

‘What?’

‘I already went to France with Mummy. When I was small.’

‘Oh.’ Rising from the armchair, I chide myself, but I’m not sure why; there is no way I could have known about their holidays. ‘Well, it doesn’t have to be France, we could try Spain, or Portugal maybe, or—’

He shakes his head, interrupting. ‘I think she has been staying there. In France. But now she is coming back.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Mummy! I can hear her.’

He is obviously troubled: the terrible grief is resurfacing again. I respond, as softly as possible, trying to find the right words, ‘Jamie, don’t be silly. Your mummy is not coming back. Because, well, you know where she is. She passed away. We’ve all seen the grave, haven’t we? In Zennor.’

The boy looks at me long, and hard, his large eyes wet. He looks outright scared. I want to embrace him. Calm him.

Jamie shakes his head, raising his voice. ‘But she isn’t. She’s not there. She’s not in the coffin. Don’t you know that?’

A darkness opens.

‘But, Jamie—’

‘They never did. They never found the body.’ His voice trembles. ‘She isn’t in that grave. They never found her. Nobody has ever found my mummy. Ask Daddy. Ask him. She isn’t buried in Zennor.’

Before I can reply, he runs out of the room. I hear his footsteps down the hall, then the same light boyish steps, running up the Grand Staircase. To his bedroom, presumably. And I am left here alone, in the beautiful Yellow Drawing Room. Alone with the intolerable idea that Jamie has placed in my mind.

Pacing across the room I find my laptop, lying on the walnut sidetable. Wrenching it open, I hesitate, take a deep breath, and then urgently type into the search engine: ‘death Nina Kerthen’.

I’ve never done this before: because there seemed no need. David told me Nina was dead. He described the tragic accident: Nina fell down the shaft at Morvellan. It was awful. I even went to see her grave in Zennor churchyard, with its poignant epitaph: This is the light of the mind.

My curiosity ended there. I didn’t want to know anything more, it was all too sad. I wanted a brand-new life with my brand-new husband, unblemished by the past.

My fingers tremble as I scroll the page and click on a couple of likely websites. Local news reports. Neatly cached.

No body has been found.

Divers are still searching, but nothing has been discovered.

The body was never found.

Slamming the laptop shut, I stare through the lead diamonds of Carnhallow’s windows: into the green-grey autumn evening, the black trees of Ladies Wood. Gazing deep into the gloom.

Jamie is right. They never found the body.

Yet there is a grave in Zennor. Complete with epitaph.

109 Days Before Christmas

Morning

It must be the most beautiful supermarket view in Britain. The new Sainsbury’s, looking out over Mount’s Bay. To my right is the crowded and steepled town of Penzance, the marina bobbing with boats and activity. On my left is the softly curving coast, disappearing towards the Lizard. And directly in front of me is the tidal island of St Michael’s Mount, surrounded by vast and shining sands, topped by its medieval castle, comical yet romantic.

There is a coffee shop on the first floor, overlooking the bay. When I come here I always order a skinny cappuccino, and then I step past the dentured pensioners nibbling their pastries and sit outside at the metal tables even when it is cold, as it is today. Cold but sunny, with clouds gathering far to the west, like a rumour.

My coffee sits on the table, neglected this morning, because I have my mobile phone pressed to my ear. David is on the other end. Listening to me, patiently. I am trying very hard not to raise my voice. Trying not to alert the pensioners. Ooh, look at her, that’s the woman who married David Kerthen …

‘So, again, why didn’t you tell me? About the body?’

‘We’ve been over this already.’

‘I know. But think of me as an idiot. I need to hear it several times to understand. Tell me again in small words, David. Why?’ I know this is difficult for him. But it is surely more difficult for me.

He answers. ‘As I said, because it’s not the sort of thing you chat about on a romantic date, is it? Oh, my wife is dead but the body is trapped in a mine, shall we have another drink?’

‘Hmm.’

Maybe he has a point, yet I still feel angry. Or perhaps unnerved. Now it is in my head I can’t get rid of the mental image. The gruesome idea of a body, preserved in icy minewater. Mouth and eyes open, suspended in lightless clarity, and staring into the silence of the drowned corridors, under the rocks of Morvellan.

David is very silent. I can sense his restrained impatience, along with his eagerness to calm me. He is a husband, but he also has a busy job, and he wants to get back to work. But I have more questions.

‘Were you worried that I might not move here? Into Carnhallow, if I knew they never found her?’

A pause. ‘No. Not really.’

‘Not really?’

‘Well, perhaps. Maybe there was a slight reluctance. It’s not something I like to dwell on. I want to forget all that, I want us to be us. I love you, Rachel, and I hope and believe you are in love with me. I didn’t want the tragedies of the past to have any bearing on our future.’

For the first time this morning I feel a twinge of sympathy for him. Possibly I am overdoing it. After all, he lost a wife, and he has a grieving son. And what would I have done in his situation?

‘I do kind of understand,’ I say. ‘And I love you, David. You know that, you surely know that. But—’

‘Look, hold on, I’m sorry, darling – I have to take this call.’

The moment I am coming to terms with all this, the agitation returns. David has put me on hold. For the second time this morning.

I tried calling him last night after I discovered the truth about Nina, but his secretary patiently told me he was in some endless, mega-important meeting, until 10 p.m. Then he simply turned his phone off without responding to my many messages. He does that sometimes when he is tired. And normally I don’t mind: his job is hard, if well rewarded, and the hours are insane.

Last night, I minded. I was shaking with fury as I kept reaching voicemail. Answer. The. Phone. This morning he finally picked up. And he has been dealing with me ever since, like a store manager with a furious customer.

As I wait for him to come back on line, I gaze at that view. It seems less appealing today.

My husband returns. ‘Hi, sorry, that damn guy from Standard Chartered, they’ve got some crisis, he wouldn’t let me go.’

‘Great, so glad you’ve got more important people to talk to. More important things than this.’

His sigh is heartfelt. ‘Darling, what can I say? I totally messed up, I know I messed up. But I did it for the best reasons—’

‘Serious?’

‘Truly. I’ve never deliberately deceived anyone.’

I want to believe him, I want to understand. This is the man I love. Yet now there are secrets.

He continues, his voice smooth, ‘To be perfectly honest, I also presumed you might know much of it already. Nina’s death was in the papers.’

‘But I don’t read the bloody papers! Novels, yes. Papers never.’

I am nearly shouting. I must stop. I can see a pensioner with a cinnamon whirl on her plate, looking at me through the glass walls. Nodding, as if she knows what’s going on.

‘Rachel?’

I lower my voice. ‘People my age don’t read newspapers, David. You must get that, no? And I had no idea who you were till I met you at that gallery. You might be a famous Cornish family. But, I’m from Plumstead. Sarf London. And I read Snapchat. Or Twitter.’

‘OK.’ He sounds genuinely mortified. ‘Again, I’m truly sorry. If you want to know the brutal details, it’s probably all online now, you can still find it.’

I let him hang on, for a second. Then, ‘I know. I printed everything out, last night. The pages are in my bag, right here.’

A pause. ‘You did? So why are you cross-examining me, like this?’

‘Because I wanted to hear your explanation first. Give you a chance. Hear your evidence.’

He allows himself a small, mournful laugh. ‘Well, now you’ve heard my evidence, Justice Daly. May I please step down from the witness box?’

David is trying to charm me. Some part of me wants to be charmed. I reckon I am prepared to let him go, after he has answered one last important question. ‘Why is there a grave, David? If there is no body, why a grave?’

His answer is calm, and his voice is sad. ‘Because we had to give Jamie some closure. He was so bitterly confused, Rachel, he still is sometimes, as we know. His mother hadn’t just died, her body had disappeared, been spirited away. He was bewildered. Kept asking where she’d gone, when Mummy was coming back. We had to have a funeral anyway, so why not have a grave? A place for her son to come and mourn.’

‘But,’ I feel prurient, yet I have to know. ‘What’s in the grave?’

‘The coat. The last thing she wore, that coat with her blood, from the mine. Read the report, from the inquest. And also a few of her favourite things. Books. Jewellery. You know.’

He has fairly and candidly answered my questions. I sit back. Half relieved, half creeped out. A body. Under the house, in the tunnels that stretch under the sea. But how many bodies are already down there, how many drowned miners? Why should another be any different?

‘Look, David, I know I’ve been pretty hard on you, it’s like, well – it was a shock. That’s all.’

‘I understand entirely,’ he says. ‘I only wish you hadn’t found out this way. How is Jamie, anyway?’

‘He’s all right, I think, he calmed down after that outburst. He seemed fine this morning. Quiet, but fine. I drove him to football practice. Cassie’s picking him up.’

‘He is getting used to you, Rachel. He is. But, as I say, he’s still confused. Look, I have to go. We can speak later.’

We say our goodbyes, and I slip the phone in my pocket.

A sea wind from Marazion, laced with the tang of salt, ruffles the printed pages as I take them out of my bag and set them on the table. There is a lot of information: I googled and printed for an hour.

Nina Kerthen’s death was, as David said, definitely a news story. It even got as far as some national papers for a day or two. And it filled the local press for weeks. And yet, it seems, there wasn’t that much to it.

It is believed Nina Kerthen had been drinking on the night in question. There is no suspicion of foul play.

Foul play. The antiquated phrase, from the Falmouth Packet, conjures ghoulish, fairytale images of a dark man in a long cloak. A Venetian assassin, grasping a beautiful woman, and throwing her in the canal. I see a pale face staring up through the watery grey. Veiled with darkening liquid, then gone.

More pages flutter in the wind. Even the southerly breezes are fanged with freshening cold, today. Distracted for a moment, I gaze out.

There is a lone man walking the flooding sands out past Long Rock. Walking aimlessly, in circles, apparently lost. Or looking for something that he will surely never find. Abruptly he turns and stares my way, as if he senses he is being watched. A strange panic fills me, a quick and sharpened fear.

I calm my anxieties. Hints of my past. Turning back to the pages, I read on. I need to know all this detail, nail it down in my mind.

The initial idea of a murder was journalistically appealing. At the time of her death the newspapers spiced their reports with the delicious possibility of homicide.

The questions were never asked outright, but clearly they hung in the air: the captions are unwritten but the meaning is implicit. Take a look at this. Isn’t David Kerthen a bit too handsome, a bit too rich, a man you want to hate? A potential killer of his beautiful wife?

When all this was ruled out, early on, the national papers gave up, while the local journalists turned, with a rather forlorn optimism, to speculations of suicide. Who would go to a mineshaft in the dark? Why take the silly risk, on a cold christmas evening?

Unfortunately for the local press, the coroner was prosaic in his verdict.

I sip my cold coffee as I scan the coroner’s summation for the third time.

It was a clear moonlit night: December twenty-eighth. Nina was seen by Juliet Kerthen, David’s mother, walking down the valley and along the cliffs, in the vicinity of the mine stacks, as she sometimes used to do, to clear her head. She had been drinking that night, with the family.

Her actions were not unusual: the area around the mine houses was a fine place to take in the spectacular view: of the brutish sea, raging at the rocky cliffs below. Especially on a bright moonlit night.

But when Nina did not return, the alarm was raised. At first it was presumed she had merely got lost, down a path, in the dark. As her absence lengthened, speculation grew more negative. Perhaps she had fallen down one of the cliffs. Bosigran, maybe. Or Zawn Hanna. No one imagined she had actually fallen down Jerusalem Shaft: she knew the dangers well enough. But then, amidst the confusion, Juliet spoke up, and made the suggestion. Search Morvellan. That was the last place she was seen, after all: walking near the mineheads.

And it had been raining heavily in the preceding days. And the mine houses were unroofed. And she was wearing heeled shoes.

The little search party – David and Cassie – made for the Shaft House, where the door was found ajar. David turned his torch-beam down the shaft. The watered pit revealed no body, but it did offer up one significant and melancholy piece of evidence. Nina’s raincoat, floating in the water. Nina had been wearing that coat. She had surely, horrifically, fallen down the pit, then thrown off the coat as she struggled to save herself. But she had nonetheless succumbed. A person would swiftly freeze in those icy waters, then sink beneath them.

The raincoat was initial and crucial evidence. Two days after the accident, divers retrieved traces of blood and splintered fingernails from the brickwork of the shaft, above the black water. They also found strands of broken hair. The DNA was matched with Nina Kerthen: it was her blood, these were her broken fingernails, this was her hair. Here was the evidence of her desperate attempts to climb out of the mine, of her doomed and failing struggle to get out of the watered shaft. Evidence that could not be faked or planted.

Taken with the eyewitness evidence from Juliet Kerthen it seemed conclusive. The coroner delivered his verdict of accidental death. Nina Kerthen was drunk, her judgement was marred, and she therefore drowned, after falling down the Jerusalem Shaft of Morvellan Mine. Her body had sunk in the freezing water and would probably never be retrieved: lost as it was in the unnumbered tunnels and adits of the undersea mine, shifted by unknowable tides and currents. Trapped beneath Carnhallow and Morvellan, for ever.

I shiver, profoundly. The wind off the bay is cutting up, and venomed with hints of rain. I need to do my tasks, and get back to the house. Binning my empty cup, I go downstairs and do my shopping and the shopping is done in seventeen minutes. It is one advantage of my frugality, born of my impoverished upbringing. A relic of Rachel Daly, from south-east London. I rarely get distracted in supermarkets.

Spinning the car on to the main road, I take a last look at St Michael’s Mount, where a shaft of September sun is shining on the subtropical garden of the St Levans, a family five hundred years younger than the Kerthens.

Then the clouds open, and the sun shines on us all. And I realize what I need to do. I believe David’s answers, but Jamie still needs help. My own stepson unnerves me, and that has to be explained: I need to read him, to decipher him, to understand. Maybe David doesn’t need to know any more. But I do.

102 Days Before Christmas

Afternoon

It’s taken me a week to pluck up the courage to come in here. David’s study. Where I will maybe learn more about Jamie. My husband has come and gone from London, the days have come and gone, palpably shortening now, I’ve done the school runs and talked to the gardener and read my books on marquetry, carpentry, and masonry, and I have hesitated maybe twelve times in front of this imposing door.

The house is deserted. Jamie is still at school; Cassie has gone shopping. Juliet is with friends for the day, in St Ives. I have an hour at least. So now I must do it. I know I am, arguably, going behind David’s back, but the grief in this house is too intense for me to keep asking questions, directly. That way is too painful for everyone. So I must be more subtle. Discreet.