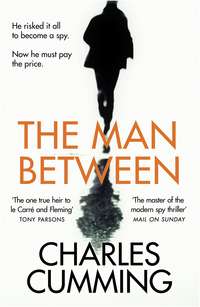

The Man Between: The gripping new spy thriller you need to read in 2018

‘Did you tell anybody that you were coming here today?’ he asked. ‘A girlfriend?’

‘I’m single,’ Carradine replied. He was surprised that Mantis had already forgotten this.

‘Oh, that’s right. You said.’ He crossed his legs. ‘What about your father?’

Carradine wondered how much Mantis knew about William Carradine. A rising star in the Service, forced out by Kim Philby, who had given his name – as well as the identities of dozens of other members of staff – to Moscow. Surely somebody at Vauxhall Cross had told him?

‘He doesn’t know.’

‘And your mother?’ Mantis quickly checked himself. ‘Oh, I’m so sorry. Of course …’

Carradine’s mother had died of breast cancer when he was a teenager. His father had never remarried. He had recently suffered a stroke that had left him paralysed on one side of his body. Carradine made a point of visiting him regularly at his flat in Swiss Cottage. He was his only surviving blood family and they were very close.

‘I haven’t told anybody,’ he said.

‘Good. So nobody has been made aware of our chat in the street?’

‘Nobody.’

Carradine looked more closely at his interlocutor. He was wearing pale blue chinos and a white Ralph Lauren polo shirt. Carradine was reminded of a line judge at Wimbledon. Mantis’s hair had been cut and his beard trimmed; as a consequence, he no longer looked quite so tired and dishevelled. Nevertheless, there was something second-rate about him. He could not help but give the impression of being very slightly out of his depth. Carradine suspected that he was not the sort of officer handed ‘hot’ postings in Amman or Baghdad. No, Robert Mantis was surely lower down the food chain, tied to a desk in London, obliged to take orders from Service upstarts half his age.

‘Let me get straight to the point.’ The man from the FCO made deliberate and sustained eye contact. ‘My colleagues and I have been talking about you. For some time.’

‘I had a feeling our meeting the other day wasn’t an accident.’

‘It wasn’t.’

Carradine looked around the room. The flat was exactly the sort of place in which a man might be quietly bumped off. No record of the meeting ever happening. CCTV footage from the lobby conveniently erased. Hair samples hoovered up and fingerprints wiped away by a Service support team. The body then placed inside a thick plastic sheet – perhaps the one covering the sofa – and taken outside to the car park. Should he say this in an effort to break the ice? Probably not. Carradine sensed that Mantis wouldn’t find it funny.

‘Don’t look so worried.’

‘What’s that?’

‘You look concerned.’

‘I’m fine.’ Carradine was surprised that Mantis had failed to read his mood. ‘In fact, it did seem a bit odd to me that a serving intelligence officer would talk so openly about working for the Service.’

‘Good.’

‘What do you mean “good”?’

‘I mean that you obviously have sound instincts.’ Carradine felt the plastic rippling beneath him. It was like sitting on a waterbed. ‘You obviously have an aptitude for this sort of thing. It’s what we wanted to talk to you about.’

‘Go on.’

‘You have a Facebook page.’

‘I do.’

‘The other day you were asking for tips about Marrakech. Advertising a talk you’re doing at a literary festival in Morocco.’

Despite the fact that C.K. Carradine’s Facebook page was publicly available, he experienced the numbing realisation that the Service had most probably strip-mined every conversation, email and text message he had sent in the previous six months. He was grateful that he hadn’t run the name ‘Robert Mantis’ through Google.

‘That’s right,’ he said.

‘Get much of a response?’

‘Uh, some restaurant tips. A lot of people recommended the Majorelle Gardens. Why?’

‘How long are you going for?’

‘About three days. I’m doing a panel discussion with another author. We’re being put up in a riad.’

‘Would you be prepared to spend slightly longer in Morocco if we asked?’

It took Carradine a moment to absorb what Mantis had said. Other writers – Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Frederick Forsyth – had worked as support agents for the Service at various points in their careers. Was he being offered the chance to do what his father had done?

‘There’s no reason why I can’t stay there a bit longer,’ he said, trying to make his expression appear as relaxed as possible while his heart began to pound like a jungle drum. ‘Why?’

Mantis laid it out.

‘You may have noticed that we’re somewhat stretched at the moment. Cyber attacks. Islamist terror. Resurrection. The list goes on …’

‘Sure.’ Carradine felt his throat go dry. He wanted to take a sip of water but was worried that Mantis would see his hand shaking.

‘Increasingly, things fall through the gaps. Agents don’t have the support they need. Messages struggle to get through. Information can’t travel in the way that we want it to travel.’

Carradine was nodding. He knew that it was better at this stage to listen rather than to ask questions. At the same time he could feel his vanity jumping up and down with excitement; the flattery implicit in Mantis’s offer, coupled with the chance to honour his father’s career, perhaps even to surpass his achievements, was hitting a sweet spot inside him that he hadn’t known existed.

‘We had a station in Rabat. It was wound up. Folded in with the Americans. Manpower issues, budgetary restrictions. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that all of this is strictly between you and me.’

‘Of course.’

‘I have a desk responsibility for the region. I need to be able to put somebody in front of one or two of our agents out there, just to reassure them that they’re a priority for London. Even though that may not be entirely the case.’

Mantis flashed Carradine a knowing look. Carradine was obliged to return it in kind, nodding as though he was on intimate terms with the complexities of agent-running.

‘I’m afraid it would require you to go to Casablanca as well as Marrakech. Ever been?’

Carradine had heard that modern Casablanca was far removed from the romantic image of the city conjured by Hollywood: a crowded, choking industrial conurbation entirely devoid of charm and interest.

‘Never. But I’ve always wanted to check it out.’

He set the mug of water to one side. In the distance Carradine could hear the sound of sirens, the familiar background soundtrack to life in twenty-first-century London. He wondered if Redmond had already been found and could scarcely believe that within hours of witnessing her kidnapping, he was being offered a chance to work as a support agent for the Service. It was as though Mantis was handing him an opportunity to prove the courage that had so recently been found wanting.

‘Can you be more precise about what exactly you need me to do?’

Mantis seemed pleased that Carradine had asked the question.

‘Writers on research trips provide perfect cover for clandestine work,’ he explained. ‘The inquisitive novelist always has a watertight excuse for poking his nose around. Any unusual or suspicious activity can be justified as part of the artistic process. You know the sort of thing. Atmosphere, authenticity, detail.’

‘I know the sort of thing,’ said Carradine.

‘All you have to do is pack a couple of your paperbacks, make sure your website and Wikipedia page are up to date. In the highly unlikely event that you encounter somebody who doubts your bona fides, just point them to the Internet and hand over a signed copy of Equal and Opposite. Easy.’

‘Sounds like you’ve got it all worked out.’

‘We do!’ Mantis beamed with his beady eyes. Carradine must have looked concerned because he added: ‘Don’t be alarmed. Your responsibilities will be comparatively minimal and require very little exertion on your part.’

‘I’m not alarmed.’

‘There’s no need – indeed no time – for detailed preparation or training. You’ll simply be required to make your way to Casablanca on Monday with various items which will be provided to you by the Service.’

‘What sort of items?’

‘Oh, just some money. Three thousand euros to be paid to a locally based agent. Also a book, most likely a novel or biography of some sort, to be passed on as a cipher.’

‘Who to?’

‘Yassine. A contact of mine from Rabat. Feeling slightly neglected, needs to have his tummy tickled but I’m too busy to fly down. We usually meet up in a restaurant, Blaine’s, which is popular with businessmen and – well – young women of low social responsibility.’ Mantis grinned at the euphemism. ‘Yassine will recognise you, greet you with the phrase, “I remember you from the wedding in London.” You reply: “The wedding was in Scotland.” And your meeting can proceed.’

Carradine was surprised that Mantis was moving at such a pace.

‘You really do have everything worked out,’ he said.

‘I can assure you this is all very normal and straightforward, as long as you can remember what to do.’

‘I can remember …’

‘As for the money, you are to leave that at the reception desk of a five-star hotel under the name “Abdullah Aziz”. A very important contact. He is owed money.’

‘Abdullah Aziz,’ Carradine was trying to remember his answer to Yassine’s question about the wedding. He wondered why Mantis was flooding him with so much information so quickly and wished that he was free to write things down.

‘Sounds easy enough,’ he said. ‘Which five-star hotel?’

‘I’ll let you know in due course.’

Carradine was seated with his palms face down on the sofa’s plastic cover. He became aware that they were soaked in sweat.

‘And what about Marrakech? What am I doing there?’

Mantis was suddenly at a loss for words. Having rushed through Carradine’s responsibilities in Casablanca, he became hesitant to the point of anxiety. Twice he appeared to be on the brink of replying to Carradine’s question only to stop himself, biting the nail on the index finger of his left hand. Eventually he stood up and looked out onto the car park.

‘Marrakech,’ he revealed at last. ‘Well, that’s where things will become slightly more … nuanced.’ The man from the FCO turned and looked into the room, slowly rubbing his hands together as he moved towards the sofa. ‘It’s why we’ve picked you, Kit. We’re going to need you to use your initiative.’

4

Mantis explained that there was a woman.

A ‘remarkable young woman, cunning and unpredictable’. She didn’t have a name – at least one that was still ‘operationally useful or relevant’ – and hadn’t been seen for ‘the best part of two years’. She was on the books at the Service but they hadn’t heard ‘hide nor hair of her for far too long’. Mantis explained that he was worried. He knew that she was in trouble and that she needed help. The Service was ‘90 per cent certain’ that the woman was living in north-west Africa under an assumed name and ‘100 per cent certain’ that she wanted to come back to the UK. She had been sighted in Marrakech in the winter and again in the Atlas Mountains only three weeks earlier. ‘Other officers and support agents’ had been looking for her in a variety of locations – Mexico, Cuba, Argentina – but all the evidence pointed to Morocco. All Carradine had to do was keep an eye out for her. The woman knew the country well and it had been easy for her to ‘disappear’ in a place with such a large number of western tourists.

‘That’s it?’ Carradine asked. The job sounded farcical.

‘That’s it,’ Mantis replied.

‘You want me just to wander around Marrakech on the off-chance I run into her?’

‘No, no.’ An apologetic smile. ‘She’s a big reader. Fan of books and literature. There’s a strong possibility that she might show her face at your festival. We just want you to keep your eyes peeled.’

Carradine struggled to think of something constructive to say.

‘If she’s in trouble, why doesn’t she come in? What’s to stop her making contact with you? Why doesn’t she go to her nearest embassy?’

‘I’m afraid it’s a good deal more complicated than that.’

Carradine sensed that he was being lied to. The Service was asking him to look for a woman who was doing everything she could to avoid being found.

‘Is she Spanish?’ he asked.

‘What makes you say that?’

‘Mexico. Argentina. Cuba. They’re all Spanish-speaking countries. Tangier is a one-hour flight from Madrid, a short hop on the boat from Tarifa.’

Mantis smiled. ‘I can see that you’re going to be good at this.’

Carradine ignored the compliment.

‘What does she look like?’ he asked.

‘I have a number of photographs that I can show you, but I’m afraid you’ll have to commit them to memory. I can give you a small passport-sized photograph to keep in your wallet as an aide-memoire, but you won’t be able to keep anything digital on your phone or laptop. We can’t risk these images falling into the wrong hands. If your phone was lost or stolen, for example, or you were asked to account for how you knew the woman …’

The task was sounding increasingly strange.

‘Who would be asking those kinds of questions?’

Mantis indicated with an airy wave of the hand that Carradine should not be concerned.

‘If you carry on behaving exactly as you have always behaved whenever you’ve been on a research trip to a foreign city, it’s very unlikely that you would ever be arrested, far less asked anything by anybody about the nature of your work for us. We take every precaution to ensure that our agents – by that I mean you, Kit – have no discernible relationship with British intelligence. Nevertheless, it goes without saying that you must never, under any circumstances, reveal anything under questioning about the arrangement we have made here today.’

‘Of course. Without saying.’

‘You and I will continue to communicate with one another en clair on WhatsApp using the number I provided to you. I will be your only point of contact with the Service. You will never come to Vauxhall, you will rarely meet any of my colleagues. As far as Morocco is concerned, you won’t tell anybody about our arrangement or – heaven forbid – start showing off about it on the phone or by email. Did you put my name into a search engine at all?’

Carradine assumed that Mantis already knew the answer to his own question, but replied truthfully.

‘No. I assumed it would be flagged up.’

‘You were right.’ He looked relieved. ‘By the same token, you mustn’t Google the names of anybody you come into contact with as a result of your work for us, nor carry with you anything that might be at all incriminating. We don’t do exploding pens and invisible ink. Does that sound like something you might be able to manage?’

Carradine felt that he had no choice other than to say: ‘Sure, no problem.’ He was perfectly capable of keeping a secret. He understood the mechanics of deceit. He was keen to do a patriotic job for his country, not least because his own professional life was so low on excitement. The only thing that concerned him was the possibility of being arrested and thrown into a Moroccan jail. But to say that to Mantis, to indicate that he was worried about saving his own skin, might have seemed spineless.

‘Mind if I use the loo?’ he asked.

‘Be my guest.’

Carradine crossed the hall and went into the bathroom. There were no towels on the rail or mats on the floor, no toothbrush or razor in the plastic mug on the basin. A stained shower curtain hung loose over the bath on white plastic hooks, many of which were bent out of shape. He locked the door and ran the tap, staring at his reflection in the mirror. It occurred to him that he was still recovering from the shock of the Redmond kidnapping and had not been thinking clearly about what Mantis was asking him to do. The job certainly promised intrigue and drama. It was a chance to perform a useful service for his country. Carradine would learn from the experience and obtain priceless first-hand research for his books. There was every possibility that he might be asked to work for the Service for a considerable period of time. In short, the situation was profoundly seductive to him.

‘Everything OK?’ Mantis asked as he came back into the living room.

‘Everything’s great.’

‘Come and have a look at these.’

He was holding an iPad. Carradine sat next to him on the sofa and looked at the screen. Mantis began flicking through a series of photographs, presumably of the woman Carradine would be asked to look for in Marrakech.

It was strange. In the same way that he had recognised Lisa Redmond as she was dragged from the car, without at first being able to put a name to her face, Carradine was sure that he had seen pictures of the woman before. She wasn’t a journalist or celebrity. She wasn’t a likely target for Resurrection. But she was some kind of public figure. Perhaps an actress he had seen on stage in London or somebody associated with a news story or political scandal. He could not work it out. It might equally have been the case that Carradine had met her at a party or that the woman had some connection to the film or publishing worlds. She was certainly not a stranger to him.

‘You look as though you recognise her.’

Carradine decided against telling Mantis that he had seen the woman’s face before. His explanation would have sounded confused.

‘No. I’m just trying to take a photograph with my eyes. Commit her face to memory.’

‘It’s a beautiful face.’

Carradine was taken aback by the wistfulness of the remark. ‘It is,’ he said as they shuttled back through the album. The woman had long, dark hair, light brown eyes and slightly crooked teeth. He assumed that most of the photographs had been culled from social media; they had a casual, snapped quality and appeared to cover a period of several years. In two of the pictures the woman was seated at a table in a restaurant, surrounded by people of her own age; in another, she was wearing a powder-blue bikini on a sunny beach, her arm encircling the waist of a handsome, bearded man holding a surfboard. Carradine assumed that he was a boyfriend, past or present.

‘He looks Spanish,’ he said, pointing at the man. ‘Was this taken in Spain?’

‘Portugal. Atlantic coast.’ Mantis reached across Carradine and quickly flicked the photo stream to the next image. ‘You were right. She has a Spanish mother. Speaks the language fluently.’

‘And her father? Where was he from?’

‘I’m afraid I can’t say.’

There was a fixed, unapologetic look on Mantis’s face.

‘And you can’t tell me her name either?’

‘I’m afraid not. It’s better that you know nothing about her, Kit. If you were to start asking the wrong questions, if you were tempted to Google her, for example, it’s not easy to say what might happen to you.’

‘That sounds like a threat.’

‘It wasn’t meant to.’

Mantis directed Carradine’s attention back to the screen. He had a good memory for faces and was confident that he would be able to recognise the woman if he came across her in Morocco.

‘How tall is she?’ he asked.

‘Couple of inches shorter than you.’

‘Hairstyle?’

‘She might have changed it. Might have dyed it. Might have shaved it all off. Anything is possible.’

‘Accent?’

‘Think Ingrid Bergman speaking English.’

Carradine smiled. He could hear the voice in his head.

‘Any other, uh …’ He reached for the euphemism. ‘Distinguishing characteristics?’

Mantis stood up, taking the iPad with him.

‘Of course! I almost forgot.’ He extended his left arm so that it was almost touching Carradine’s forehead. ‘The woman has a tattoo,’ he said, tapping the wrist. ‘Three tiny black swallows just about here.’

Carradine stared at the frayed cuffs of Mantis’s shirt. Veins bulged on his forearm beneath a scattering of black hairs.

‘If it’s a tattoo,’ he said, ‘and she’s trying not to get recognised, don’t you think she might have had it removed?’

Mantis moved his hand onto Carradine’s shoulder. Carradine hoped that he wouldn’t leave it there for long.

‘You don’t miss a trick, do you?’ he said. ‘We’ve obviously picked the right man, Kit. You’re a natural.’

5

Mantis said nothing more about the tattoo. Carradine was told that if he spotted the woman, he was to approach her discreetly, ensure that their conversation was neither overheard nor overseen, and then to explain that he had been sent by British intelligence. He was also to pass her a sealed package. This would be delivered by the Service before he left for Morocco.

‘I’m assuming I can’t open this package when I receive it?’

‘That is correct.’

‘Can I ask what will be inside it?’

‘A passport, a credit card and a message to the agent. That is all.’

‘That’s all? Nothing else?’

‘Nothing else.’

‘So why seal it?’

‘I’m not sure I understand your question.’

Carradine was trying to tread the fine line between protecting himself against risk and not appearing to be apprehensive.

‘It’s just that if my bags are searched and they find the package, if they ask me to open it, how do I explain why I’m carrying somebody else’s passport?’

‘Simple,’ Mantis replied. ‘You say that it’s for a friend who left it in London. The same friend whose photo you’re carrying in your wallet.’

‘So how did she get to Morocco without a passport?’

Mantis took a deep breath, as if to suggest that Carradine was starting to ask too many questions. ‘She has two. One Spanish, the other British. OK?’

‘What’s my friend’s name?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I need to know her name. If it’s on the passport, if I’m carrying her picture around, they’ll expect me to know who she is.’

‘Ah.’ Mantis seemed pleased that Carradine had thought of this. ‘The surname on the passport is “Rodriguez”. Christian name “Maria”. Easy enough to remember.’

‘And mundane enough not to draw attention to itself.’

‘It does have that added dimension, yes.’

They remained at the Lisson Grove flat for another half-hour, going over further practical details of Carradine’s trip, including protocols for contacting Vauxhall Cross in the event of an emergency. Mantis insisted that they meet at the flat when Carradine returned from Marrakech, at which point he would be debriefed and given payment, in cash, for any expenses he had run up in Morocco.

‘Feel free to stay somewhere decent in Casablanca,’ he said. ‘We’ll cover your costs, the extra flight as well. Just keep accurate receipts for the bean counters. They’re notoriously stingy when it comes to shelling out for taxis and train tickets.’

As Carradine was leaving, Mantis handed him two envelopes, each containing €1,500. There was no limit to the amount of foreign currency he was permitted to bring into Morocco and Mantis did not think that €3,000 would be considered suspicious. He told Carradine that the sealed package containing the passport and credit card would be delivered to his flat in Lancaster Gate the following day, as well as the novel which was to be used as a book cipher. Mantis reiterated the importance of leaving the sealed package intact, unless Carradine was instructed to open it by law enforcement officials in the UK or Morocco. He did not give an explanation for this request and Carradine did not ask for one. Carradine assumed that the package would contain sensitive documents.

‘Good luck,’ Mantis said, shaking his hand as he left. ‘And thanks for helping out.’

‘No problem.’

Carradine walked out onto Lisson Grove in a state of confusion. He was bewildered by the speed with which Mantis had acted and strung out by the painstaking assimilation of so much information. It seemed bizarre that he should have been asked to undertake work on behalf of the secret state – particularly after such a cursory meeting – and wondered if the entire episode was part of an elaborate set-up. Clearly the content of his novels, the depictions of tradecraft, his observations about the burdens of secrecy and so forth, had convinced the Service that C.K. Carradine was possessed of the ideal temperament to work as a support agent. But how had they known that he would agree so readily to their offer? While working for the BBC in his twenties, Carradine had spoken to three veteran foreign correspondents – two British, one Canadian – each of whom had been tapped up by their respective intelligence services overseas. They had turned down the opportunity on the basis that it would interfere with the objectivity of their work, undermine the relationships they had built up with local sources and potentially bring them into conflict with their host governments. Carradine wished that he had shown a little more of their steadfastness when presented with the dangled carrot of clandestine work. Instead, perhaps because of what had happened to his father, he had demonstrated a rather old-fashioned desire to serve Queen and country, a facet of his character which suddenly seemed antiquated, even naive. He was committed to doing what Mantis had asked him to do, but felt that he had not given himself adequate protection in the event that things went wrong.