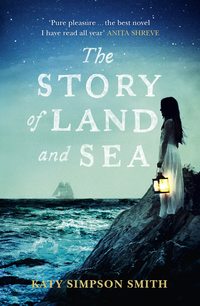

The Story of Land and Sea

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Katy Simpson Smith 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Jacket illustration by TK

Katy Simpson Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007564002

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007563999

Version: 2015-06-22

Dedication

FOR

MY FATHER

There is a land of pure delight

Where saints immortal reign;

Infinite day excludes the night,

And pleasures banish pain.

There everlasting spring abides,

And never-withering flowers;

Death like a narrow sea divides

This heavenly land from ours …

But timorous mortals start and shrink

To cross this narrow sea,

And linger shivering on the brink,

And fear to launch away …

Could we but climb where Moses stood

And view the landscape o’er,

Not Jordan’s stream, nor death’s cold flood,

Should fright us from the shore.

ISAAC WATTS

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: 1793

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Two: 1771–1782

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part Three: 1793–1794

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Acknowledgments

A Conversation with Katy Simpson Smith

Author’s Note

About the Author

Also by Katy Simpson Smith

About the Publisher

1

On days in August when sea storms bite into the North Carolina coast, he drags a tick mattress into the hall and tells his daughter stories, true and false, about her mother. The wooden shutters clatter, and Tabitha folds blankets around them to build a softness for the storm. He always tells of their courting days, of her mother’s shyness. She looked like a straight tall pine from a distance; only when he got close could he see her trembling.

“Was she scared?”

“Happy,” John says. “We were both happy.”

He watches Tab pull the quilt up to her chin, though even the storm can’t blow away the heat of summer. She is waiting to hear his secrets. But it is hard to describe how it feels to stand next to someone you love on the shore at dusk. He didn’t have to see Helen to know she was there. Something in her body pulled at something in his, across the humid air between them.

“When you’re older,” he says, and she nods, familiar with this response.

“Why don’t you ever tell about the ship?” she asks. “All the things you must have seen with her.”

He looks down the hall at the shadows whipping across the slats and holds a finger to his lips. “Can you hear any birds?”

Tab slips into the kitchen for an end of bread in the darkness of the storm. She will keep asking him until he tells her. In the quilts again, she tucks close against him. As the wind rattles through the palmettos and the rain melts the window glass, John sings one of his sailing tunes to soothe her. Tabitha calls out, “Louder!” and he rises to his feet, unsteady on the mattress, waving his browned hands to the melody. His voice carries through the quiet rooms.

He doesn’t tell her about the day he walked Helen onto a ship with a captain he knew from his pirate days, one small bag between them, and they curled beneath the gunwale until the frigate had pulled its anchor and filled its sails and was tacking through the shoals out of the bay. Only when the mate gave a wink did they stand—Helen wobbling, clutching him for support, laughing like a girl, her hair pulled by the wind—and watch the town slowly shrink until it was no bigger than a piece of driftwood, a brown and gold splotch against the shore.

He doesn’t tell Tab about the beauty of her mother as she struggled to find some dignity on a vessel made seaworthy by its layers of filth. A year they were on that ship, married and her with the seed of a child in her by the end, and Helen transformed from some kind of pristine saint to the sunburned woman who tucked her skirts up to scrub the deck with him, who wrapped her hands around his when he fished off the side of the ship in the evenings. Could such a woman really have come back to live in the world again? The curses she learned, the brownness of her skin, the way her laughter got louder, as though to compete with the waves.

Who will Tabitha be when she becomes a woman?

After the storm, they walk to the shore to see what the ocean has relinquished. Fallen leaves and branches line the way. Half buried in sand is the cracked husk of a horseshoe crab. Tab scrapes her fingernails along its papery hide and leaves it for the waves to eat again.

It is 1793, and they live in Beaufort in a four-room house, two above and two below, built by a childless cousin in the lumber trade who was killed by a falling pine. One block north of the water, three blocks east of the store where John sells sundries. In the summer the doors hang open, front and back, and a salt breeze snakes through the hall. In thunder, the windows clamor. The girl’s room upstairs faces the marsh and smells of fish in the morning and in the afternoon catches all the southern light. On moonless nights she sleeps with her father for fear of riding witches.

Mrs. Foushee leads the school in town, where children, mostly girls, pass time if their mothers are not birthing or poor. Their small hands rub the grooves in wooden tables and slip between the pages of spelling books. The letters dance for them. Mrs. Foushee is a soldier’s wife and sleeps in his bed and listens to him remember the Revolution, but in the schoolroom she wearies of duty. For most of the day she sits, and has the children bring their work to her. She lets them out early or fails to call them back from dinner. She idles with her embroidery, sucks on candies, and sometimes dozes. The girls creep to her chair and watch, some fondling the pink brocade of her skirts, others plucking strands of silver hair fallen on her bosom and setting fire to them for the smell of it. Her eyelids droop; her mouth, still full in middle age, hangs limp. She taught Tab’s mother too.

At nine, Tabitha knows her alphabet and most small words and can count up shillings and pence on her fingers. She can play three melodies on the church organ, and if taken to France, she could ask for bread and water. This is also the bulk of Mrs. Foushee’s knowledge. Most days Tab lets the woman sleep and the other pupils plait their hair. She stares instead through the open door to the ocean, which she knows better than she knows her mother.

The town is older now, in the way that some towns age; most of the young people have grown up. Some went to war and died, and others took their small inheritances and moved to Wilmington or Raleigh. When John’s cousin was felled, no other relative would return to take his house in Beaufort. But John had a wife with child, and the sea was no place for a baby. The remaining families in town live in a slender band along the ocean, just a few streets deep. Those with money have collected the surrounding fields for rice or lumber, and beyond the plantations, marsh and forest unroll inland. A single road through this wilderness binds Beaufort to New Bern. The town seems to be slowly cutting itself off.

Tab doesn’t know many children. There are Mrs. Foushee’s pupils, some ragged boys that belong to poor farmers on the edge of town, and the children of slaves, whom she can spot in the fields by their smallness. They are half steps in the long rows of bent bodies. They rarely come into town, and when they do, they don’t look up. Tab knows her father has some acquaintances among the slaves, but she doesn’t think this is so unusual. Silent threads run in all directions through the town, and Tab is not blind. He never brings them to meet her, though, or speaks to them outright. Tab doesn’t know the rules about this. One woman comes into the store sometimes with eggs to sell and a little boy by her side, the same size as Tab. John looks at them hard, and the woman looks hard back, but their words are mostly ordinary. The boy tries to touch everything in the store. He feels the barrels and hoes and sacks of dried corn like they were all silk. He smiles at Tab, as though he knew everything that she knew. But Tab is not his friend, nor is she the friend of the powdery girls in Mrs. Foushee’s schoolroom or the boys who throw rocks on the edge of town. She has her father.

Summer mornings when Mrs. Foushee is ill or Tabitha’s blood is jumping, the girl walks to the marshes along the waterfront and swims with slow strokes to the sandbar between the sound and the ocean. She lies on the grit, limbs spread, fingers and toes burying themselves in warmth. Eyes closed, she sees battles fought on water. Ships—French, British, and ghost—with cannon booming and flags snapping, their precarious shapes lit by the piling clouds of summer. Bursts of gunfire paint the sunset.

She digs channels by the shore to let the water in and builds moats and islands of defense. Oak leaves pummel each other, and moss bits leap into the shallow salt water, bodies flung out to sea. Cannonball pebbles land on the leaves, dooming them, sending their wreckage to the depths for stone crabs to scuttle over. There are no mercies in this play.

The battle over, the leaves drowned, Tabitha searches for treasure. She has sewn large pockets onto the front of her dresses to carry home the pink-eared shells and dry fish bones. She used to leave her findings in a pit at the center of the island, but a storm scattered them all. Now she takes them with her. Her bedroom becomes wild with the ocean’s debris. She steps on something sharp and pulls broken brass from a sucking cove where the water seeps in. A shard of armor, she assumes. Her father, not knowing the best thing for her, lets her wander.

At dusk, the marshes turn purple and heavy. From the sandbar, the dimpled muck of the shore smooths over. The reeds quiver with bitterns. A strand of clouds sinks to the west, blanketing the last pink edge. When Tab slips into the dark water, silver-brushed, a burst of herring gulls cries out, winging up. She opens her eyes beneath the surface, letting her body float, her hair drift. Her shift gathers water. A dark small shape passes below her, and she lifts her head up fast, gasping. A strand of hair slides into her mouth when she sucks in air. She begins to kick and reach and in a few minutes is ankle-deep again in brown grime, her hands reaching for stalks to pull her feet from the mud. Her pockets still hang heavy with treasure. Her wet legs collect sand all the way home.

On Sundays, Asa comes in a brown suit. Though he and John rarely speak of Helen, Asa’s green eyes remind both men of her. He carries a book in his hands and waits in the hall for his granddaughter. John asks him to sit, and he shakes his head, staring out the open back door. John asks how his trees grow, and Asa says, “Passable.” John leaves his father-in-law standing there and retires to the parlor to read the weekly papers. Later in the morning, John will wander down to the harbor and greet the ships that dock, looking for old friends amidst the crews. Tabitha comes downstairs in a pinching dress, her only one without pockets, and slips her hand into her grandfather’s without a smile. She says good-bye to John, and they walk the five blocks to church. The building is brick and stands uneasily on stone pillars. Asa is Anglican, but Anglicanism is dying out, and his old church was taken over by Methodists. Most of the Anglicans retreated to this smaller chapel, where they have realigned with the Episcopalians. He cannot keep track of the names of Christianity. People are still searching for what they used to know. Here there is no stained glass and the pine floorboards are warping. The church does have a little square tower and a cupola with a bell, but from the street one can see they rest at a tilt.

Sitting in the pew with his granddaughter, he wishes for cushions. When he was a boy, services were held in the courthouse; he had a gilded Bible and his bottom could rest on a pillow while he listened to the Lord’s word. But now the sons are moving away, leaving their fathers’ farms, and churches are left wanting. The town talked of building a canal to join the two rivers on the way to New Bern so boats could pass with goods, but the men who had the funds were loath to spend them, and Beaufort—which could have controlled the inland trade—became stagnant, and then began to shrink. The goodness in the world he knew has contracted; the common feeling they had under royal rule has turned to self-interest. Men grasp at money instead of virtue. All the men he knows are common bandits. He hopes God is watching.

Tabitha, who swings her legs when she is forced to sit, kicks the back of his ankle, sending his leg knocking into the pew in front of him. The minister pauses, and resumes. Asa pinches her wrist and glares.

The Reverend Solomon Halling stands at the pulpit and makes gentle flourishes with his hands. The pulpit is made of pine, carved with a large flower and several smaller flowers, which might also be four-petaled crosses. Asa always wonders if a woman made it. Halling comes down from New Bern a few times a year; mostly, they listen to vestrymen or sing songs amongst themselves. The congregation has been halved in recent years. Instead of gathering at the front, they keep their family seats, the spaces between them widening. Halling reminds the listeners what it is to be Episcopalian, that it is merely Anglicanism without the thrall to monarchy. A few women fidget in the pews. A child sneezes and then begins to cry, so Halling shifts to a hymn. The people stand, and those who earn their living by the sea rub their woolen vests. They blush to hear the sound of their own voices.

During the hymns, Asa always hears his absent daughter. The clarity of her tone once reminded him of his wickedness. He is one of the men who comes to church to punish himself, though of course there is pleasure in this penance. When he glances down at his granddaughter, she seems like a stranger.

After the parishioners have offered prayer and been exhorted to goodness and donation, the Reverend Dr. Halling stands on the sagging steps and shakes their hands. On this Sunday, Asa gives him a half pound for the new church and pushes Tabitha forward to shake his hand. Though new to the parish, the minister is worn, with graying locks frizzed around his shoulders and dull brown eyes. He was a surgeon during the war, and after the piecing together of men’s bodies, the care of their souls has finally tired him. When he smiles, his teeth catch on his lip, so he is ever adjusting his mouth to bring it to stasis.

“My granddaughter,” Asa says, his hand tight on her shoulder. Tabitha wipes her palms on her dress. “She and her father are wayward in faith.”

Halling nods. “Has she her own hymnal?” He slips back into the church, upsetting a flock of older women who croon after him, and in a few moments returns with a tattered brown book and hands it to Asa. “Mostly Watts,” he says.

“I fear I am her only guidance,” Asa says.

Halling shakes his head and holds his hand out flat, palm up. “You forget the Lord.” He turns back to the crowd, which is still absorbing the presence of ordination.

Tab pulls on her grandfather’s hand. The tides are rolling out, and she can smell the fishermen’s catch, can hear the gasping holes the crabs make in the sand.

Asa holds the book on the walk home, wondering about the rightness of letting a heathen child possess the word of God. Where is the purpose in watering fallow fields? He wishes there was a minister year-round. His God is a fickle one, and Asa does not always comprehend the trajectories of the lives around him. He looks only for evidence of justice. He looks for reasons why he has been so punished.

In the summer of 1783, his daughter, Helen, returned to him after a year of dissipation. She had been seduced by John, a common soldier, married without her father’s blessing, abandoned her inheritance to set sail with the soldier on a black-flagged ship, and had come home with a belly full of child. Asa waited for God’s fist to fall on her husband. As John built new shelves in the merchant’s store in which he had purchased a share, Asa waited for the hammer to slip and strike John’s hand, the board to crack upon his head. During August storms when John and Helen would stand by the water, arms entwined, bodies warm for each other, Asa waited for the swells to pull John in, leaving his daughter alone on the shore. He wanted her back, untouched. He watched as they fixed up the house left to them by John’s cousin, painting it fresh white, filling it with oddments from the sea, tilling the grit outside for potatoes and corn. He never saw them sad or thoughtful. Their joy was the devil’s mark.

When her time came in October, a storm swept in from the southeast and whipped up the waves. Asa wanted to carry his daughter inland for the birth, to protect her among the trees, but she clung to the house she and John had adorned. If her child was going to know the world, she wanted it to know all, the gale and breeze alike. Despite Helen’s requests, Asa refused to pray for her. He had prayed for his own wife during a similar storm, during the same mortal passage, and she had been taken. He could not pray again, not in the same way. But he came to her when she began to labor, and he waited with her, as he had not waited with his wife, and the whole scene was a mirror to him, as if God was showing him what he missed the first time.

He and John carried water for the midwife, tore scraps of linen, carried more water. They did not speak, and when John reached for his arm, Asa pulled away. Neither man should have been a witness, but Asa insisted; he would no longer let women control this moment. They stood in the corner of the room with their arms crossed, eyes on the floor. Looking over the shoulder of the midwife, whose hands were busy with cloth and water and touch, Helen begged her father to tell her if this was how it usually happened, and whether her mother had felt this way. She was a child again, and needed his voice. He nodded and said everything was just as it should be, though he had not seen his wife in labor and wouldn’t know what was ordinary, but yes, no reason to worry, and surely Helen had the strength for it. But she was not listening.

As the storm tunneled through the streets of Beaufort, an infant arrived: red and angry and screaming over the howls of wind. The midwife placed the child in a basket while she pressed vinegar rags to the mother’s wounds. John and Asa stood beyond the cast of candlelight, staring at the weeds of hair pressed against Helen’s white cheeks, listening to the thinness of her breaths. She began to weep.

Asa left in the morning, after the squall had blown away north, and took his daughter’s body with him. He said he would come back for the living child.

When Asa goes to church, he carries a list of sins in his heart, waiting for forgiveness.

Summer blends into fall. Yellow warblers and flocks of bobolinks arrive on the salt marshes, and sandpipers poke along the mudflats, watching for holes. In the forests around Beaufort, the sumacs turn fiery red, and the wild grapes grow purple and fat. By October, the evenings are finally cool.

Tab cannot sleep the night before her tenth birthday. She has a rasp in her throat that feels like dry biscuits. Kneeling instead by the window, wrapped in her mother’s shawl, she traces patterns in the stars, fingering out dogs and chariots on the frosting pane, her chin propped on the sill. She closes her eyes only to imagine the model ship that might appear wrapped in brown paper at dawn. It has three masts and is made of thin paneling stained nut brown. Its sails are coarse linen, and a tiny wheel spins behind the mizzen-mast. Netting hangs along its decks. On the starboard side, a small trapdoor is cut into the planks that you can lift and peer through into the hold. She would fill its empty belly with detritus. Acorns, feathers, moss. She saw it in a shop in New Bern on their last visit there to purchase fabric for the store. Tab made a point of standing still before the window until her father, strides ahead, missed her and turned.

“Ships, eh?” he said, and tugged gently at the back collar of her dress.

“Tell me something again,” she said, and as they walked away from the shining toy boat, he began another tale about her mother, and she knew that he had known, that he had seen the want in her eyes and understood.

In the carriage home, her father hid a large package beneath the seat and winked at her. All she had to do was wait for it to come into her hands.

John sleeps sometimes in his bedroom across the slanting hall from Tabitha, but there are nights when he can smell his wife’s body in the bed and he takes his blankets downstairs. He finds a space among the furniture in the parlor—pieces given to his wife by her parents, and to them by their parents—on rugs bartered or stolen from vessels he has hailed on the saltwater rises, below paintings of flat faces and flat children holding shrunken lambs, between cabinets of glass bottles, Spanish gold, musket balls, a rusted crown, bells. The remnants of booty that are now only treasure to a child. There is a mirror in this room with a peeling silver back, and sometimes in its spaces, Helen appears, wearing blue, her dark hair in braids behind her head, curls sprouting. Her green eyes depth-colored. He talks to her here, or he is afraid, the way her eyes follow him, and he takes his blankets into the hearth room, where pots with grease line the fireplace and shelves hold dry goods, bolts of fabric, sacks of meal. This is where he keeps the store’s excess. When customers ask for mustard seed, he brings them here, or says it must be delivered special and so gets a few pence extra. They have never wanted, he and his child. And still her phantom moves through the rooms, reminding him of what they lack.