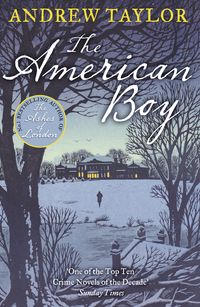

The American Boy

‘I don’t deny I took a drop of something to keep out the cold.’

‘Drank so much the Last Judgement could have come without him noticing anything out of the way,’ the constable translated. He nodded towards the silent shape that lay on the trestles. ‘You’ve only got to look at him to see he didn’t go quietly. Ain’t that right, Mr Grout?’

The clerk ignored the question. He turned aside and tugged at the sacking over one of the windows, which were small and set high to dissuade thieves. The sacking fell away, revealing an unglazed square. Pale winter daylight spread reluctantly through the little cabin. Orton whinnied softly, as though the light hurt him.

‘Stow it,’ said the constable.

‘He moved,’ Orton whispered. ‘I take my oath on it. I saw his hand move. Just then, as God’s my witness.’

‘Your wits are wandering,’ Grout said. ‘Bring the lantern. Why is there not more light? Perhaps we should have left the poor man where he lay.’

‘There’s foxes, and a terrible deal of rats,’ Orton said.

Grout motioned me to approach the makeshift table. The body was entirely covered with a grey blanket, with the exception of the left hand.

‘Dear God!’ I ejaculated.

‘You must brace yourself, Mr Shield. The face is worse.’

His voice seemed to come from a great distance. I stared at the wreck of the hand. I bent closer and the constable shone the light full on it. It had been reduced to a bloody pulp of flesh, skin and shockingly white splinters of bone. I fought an impulse to vomit.

‘The top joints of the forefinger appear to be missing,’ I said in a thin, precise voice. ‘I know Mr Frant had sustained a similar injury.’

Grout let out his breath in a sigh. ‘Are you ready for the rest?’

I nodded. I did not trust myself to speak.

The constable set down the lantern on the corner of the door, raised himself on tiptoe, took the top two corners of the blanket and slowly pulled it back. The figure lay supine and as still as an effigy. The constable lifted the lantern and held it up to the head.

I shuddered and took a step back. Grout gripped my elbow. My mind darkened. For an instant I thought the darkness was outside me, that the flame in the lantern had died and that the day had slipped with tropical suddenness into night. I was aware of a powerful odour of faeces and sweat, of stale tobacco and gin.

‘He should think himself lucky,’ Orton wheezed at my shoulder. ‘I mean, look at him, most of him’s hardly touched. Lucky bugger, eh? You should see what roundshot fair and square in the belly can do to a man. Now that’s what I call damage. I remember at Waterloo –’

‘Hold your tongue, damn you,’ I said, obscurely angry that this man seemed not to have spent the battle cowering in the shadow of a dead horse.

‘You block the light, Orton,’ Grout said, unexpectedly mild. ‘Move aside.’

I closed my eyes and tried to shut out the sights and sounds and smells that struggled to fill the darkness around me. This was not a battle: this was merely a corpse.

‘Are you able to come to an opinion?’ Grout inquired. ‘I realise that the face is – is much battered.’

I opened my eyes. The man on the trestle table was hatless. There were still patches of frost on both clothes and hair. It had been a cold night to spend in the open. He wore a dark, many-caped greatcoat – not a coachman’s but a gentleman’s luxurious imitation. Underneath I glimpsed a dark blue coat, pale brown breeches and heavy riding boots. The hair was greying at the temples, cut short.

As to the face, it was everyone’s and no one’s. Only one eye was visible – God alone knew what had happened to the other – and it seemed to me that its colour was a pale blue-grey.

‘He – he is much changed, of course,’ I said, and the words were as weak and inadequate as the light from the lantern. ‘But everything I see is consonant with what I know of Mr Frant – the colour of the hair, that is to say, the colour of the eyes – that is, of the eye – and the build and the height as far as I can estimate them.’

‘The clothes?’

‘I cannot help you there.’

‘There is also a ring.’ Grout walked round the head of the table, keeping as far away from it as he could. ‘It is still on the other hand, so the motive for this dreadful deed appears not to have been robbery. Pray come round to this side.’

I obeyed like one in a trance. I was unable to look away from what lay on the table. The greatcoat was smeared with mud. A dark patch spread like a sinister bib across the chest. I thought I discerned splinters of exposed bone in the red ruin of the face.

The single eye seemed to follow me.

‘Now take cavalry,’ Orton suggested from his dark corner near the stove. ‘When they’re bunched together, and charging, so the horses can’t choose where they put their hooves. If there’s a man lying on the ground, wounded, say, there’s not a lot anyone can do. Cuts a man up cruelly, I can tell you. You wouldn’t believe.’

‘Stow your mag,’ said the constable wearily.

‘Least he’s got a peeper left on him,’ Orton went on. ‘The crows used to go for the eyes, did you know that?’

The constable cuffed him into silence. Grout held the lantern low so I could examine the right hand of the corpse. Like the left, it had been reduced to a bloody pulp. On the forefinger was the great gold signet ring.

‘I must have air,’ I said. I pushed past Grout and the constable and blundered through the doorway. The clerk followed me outside. I stared over the desolate prospect of frosty mud and raw brick. Three pigeons rose in alarm from the bare branches of an oak tree that survived from a time when the land had not been given over to wild schemes and lost fortunes.

Grout pushed a flask into my hand. I took a mouthful of brandy, and spluttered as the heat ran down to my belly. He walked up and down, clapping his gloved hands together against the cold.

‘Well, sir?’ he said. ‘What is your verdict?’

‘I believe it is Mr Henry Frant.’

‘You cannot be certain?’

‘His face … it is much damaged.’

‘You remarked the missing finger.’

‘Yes.’

‘It supports the identification.’

‘True.’ I hesitated and then burst out: ‘But who could have done such a thing? The violence of the attack passes all belief.’

Grout shrugged. His eyes strayed towards the nearest of the half-built houses.

‘Would you care to see where the deed was done? It is not a sight for the squeamish, but it is as nothing compared with what you have already seen.’

‘I should be most interested.’ The brandy had given me false courage.

He led me along a line of planks that snaked precariously across the mud. The house was a house in name only. Low walls surrounded the shallow pit of the cellar, perhaps two or three feet below the surface of the field in which we stood. Grout jumped into it with the alacrity of a sparrow looking for breadcrumbs. I followed him, narrowly avoiding a pool of fresh excrement. He pointed with his stick at the further corner. Despite his warning, there was little to see, apart from puddles of icy water and, abutting the brickwork in the angle of the wall, an irregular patch of earth which was darker than the rest, darker because shadowed with Henry Frant’s blood.

‘Were there footprints?’ I asked. ‘Surely such a struggle must have left a number of marks?’

Grout shook his head. ‘Unfortunately the scene has had a number of visitors since the deed was committed. Besides, the ground was hard with frost.’

‘When did Orton make the discovery?’

‘Shortly after it was light. When he woke, he found that while he slept someone had wedged the door of the shed. He had to crawl out through one of the windows. He came here to relieve himself, which was when he found the corpse.’ Grout’s nose wrinkled. ‘First he alerted a neighbouring farmer, who came to gawp with half a dozen of his men. Then the magistrates. If there were footprints, or other marks, they will not be easy to distinguish from those which were made before or afterwards.’

‘What of Mr Frant’s hat and gloves? How did he come here? And why should he come at that time of evening?’

‘If we knew the answers to those questions, Mr Shield, we would no doubt know the identity of the murderer. We found the hat beside the body. It is in the shed now, and has Mr Frant’s name inside. And the gloves were beneath the body itself.’

‘That is odd, is it not, sir?’

‘How so?’

‘That a man should remove his gloves on such a cold night.’

‘The affair as a whole is a tissue of strange and contradictory circumstances. Mr Frant’s pockets had been emptied. Yet the ring was left on his finger.’ Grout rubbed his pointed nose, whose tip was pink with cold. ‘The principal weapon might have been a hammer or a similar instrument,’ he went on, the words tumbling out at such a rate that I realised that he, too, was not unmoved by the dreadful sight on the trestle table. ‘Though it is possible that the assailant also used a brick.’

He scrambled out of the cellar and we walked slowly back towards the shed.

‘They may have come here on foot,’ Grout said. ‘But more likely they rode or drove. Someone will have seen them on the way.’

‘Ruined men can be driven to desperate measures, and it is not impossible that one of those whom Mr Frant injured has had his mind overturned by his troubles, and has sought revenge.’

Grout gave me a long look. ‘Or this might be the work of a jealous lover. Or a madman.’

There was nothing more for me to do at Wellington-terrace. As Mr Grout drove me back to school, I sat in silence beside him, my mind too full for conversation. We passed the flask to and fro between us. It was empty by the time we drew up outside the Manor House School.

I said, ‘May I tell Mr Bransby what has passed?’

Grout shrugged. ‘He either knows or surmises everything you or I could tell him. So will the whole neighbourhood in an hour or two.’

‘There is the matter of the boy. Mr Frant’s son.’

‘Indeed. Mr Bransby must do what he thinks fit on that head.’ He bobbed his nose towards me. ‘I do not know how the magistrates will proceed, and if I did know, it would not be proper for me to tell you. However, there will be an inquest, and you may be required to attend. In the meantime, though –’ he spread his arms wide ‘– there will be talk. That much I do know.’

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

IN THE EVENING of that terrible day, I smoked a pipe with Dansey in the garden after the boys were in bed. We walked up and down, huddled in our greatcoats. Soon after my return, Mr Bransby had summoned Charlie Frant. The boy had not been seen since. A message had been sent for Edgar Allan to take his friend’s possessions to Mr Bransby’s side of the house.

‘It is said a man has been arrested already,’ Dansey said softly.

‘Who?’

‘I do not know.’

I bowed my head. ‘But why did the murderer mutilate the body?’

‘A man in search of revenge is a man out of his senses. If it was revenge.’

‘Yes, but the hands?’

‘In Arabia, they cut off the thief’s hands. We used to do it here, I believe, or something similar. Crushing the hands in the manner you described might be another form of the practice. Perhaps Mr Frant’s killer believed his victim was a thief.’

Our pipes hissed and bubbled. At the foot of the garden, we turned, and stood for a moment under the shelter of the trees looking back at the house.

Dansey sighed. ‘Come what may, this affair will make a considerable noise in the world. Pray do not think me impertinent if I speak for a moment in the character of a friend, but I would advise you to keep your own counsel.’

‘I am obliged to you. But why do you make such a point of this?’

‘I hardly know. The Frants are great folk. When great folk fall, they bring down smaller folk in their train.’ He sucked on his pipe. ‘It is a thousand pities you were called upon to identify the body. You should not have had to appear in this matter at all.’

I shrugged, trying unsuccessfully to push from my mind the memory of that bloodied carcass I had seen in the morning. ‘Shall we go in? It grows cold.’

‘As you wish.’

It seemed to me that there was a note of regret in Dansey’s voice. We walked slowly back to the house – slowly, because his footsteps lagged. The moon was very bright, and our feet crunched on the silver lawn. The house reared up in front of us, the moon full on its garden front.

Dansey laid a hand on my arm. ‘Tom? I may call you that, may I not? Pray call me Ned. I do not wish –’

‘Hush,’ I said. ‘Look – someone is watching us. Do you see? The third attic from the left.’

The window belonged to the chamber Morley and Quird had shared with Charlie Frant. We quickened our pace, and a moment later passed into the house.

‘Moonlight plays strange tricks,’ Dansey said.

I shook my head. ‘I saw a face. Just for a moment.’

That night I slept dreamlessly, though I had feared my nightmares of carnage would return after the sight I had seen in Jacob Orton’s shed.

In my waking hours, the school itself was better than any medicine. For the next few days, our lives continued their placid course, seemingly unchanged. Nevertheless, news continued to reach us from the outside world. The man who had been taken into custody was the brother of the builder, Mr Owens, who had committed suicide. The brother was said to be subject to fits of ungovernable rage; reputable witnesses had heard him utter threats against Henry Frant, whom he held responsible for his brother’s suicide; he was a violent man, and had nearly killed a neighbour whom he suspected of making sheep’s eyes at his wife. But the following day, the magistrates ordered his release. It transpired that he had spent the evening of the night in question drinking at his uncle’s house, and had shared a bed with his cousin; and so his family would give him an alibi.

The inquest came and went. I was not called to give evidence, much to my relief and to Mr Bransby’s. Mr Frant’s confidential clerk, a man named Arndale who had known him for the better part of twenty years, had no hesitation in identifying the body as his master’s. The jury brought in a verdict of murder against person or persons unknown.

Despite the horrific manner of his death, there were few expressions of grief for Mr Frant or of sympathy for his widow. As information emerged about the collapse of Wavenhoe’s Bank and the reasons for it, the public prints hastened to condemn him.

The extent of Frant’s depredations was never known for certain, but I heard sums ranging from £200,000 to upwards of half a million. Many of the bank’s customers, secure in the good name of Wavenhoe’s, had appointed Mr Wavenhoe and Mr Frant as their trustees. As such, Frant had purchased hundreds of thousands of pounds’ worth of stock in the three per cent Consols. In the last three years, he had forged powers of attorney enabling him to sell this stock. Mr Wavenhoe had signed the documents put before him, though doubtless he was unaware of their significance. The name of a third partner, another of the trustees, had been forged on all occasions, as had several of the subscribing witnesses. Mr Frant had converted the proceeds from these sales to his own use, retaining sufficient funds to allow him to pay dividends to the bank’s customers, thereby preventing their suspicions from being aroused.

Arndale, Frant’s clerk, claimed to have known nothing of this. (Dansey thought the man had avoided prosecution by co-operating with the authorities.) Arndale confirmed that the house had been badly hit by the withdrawal of Mr Carswall’s capital. He also testified that the bank had made many advances to speculative builders, which had rendered necessary a system of discounting, and that Mr Frant had subsequently been obliged to make further advances to these persons, in order to secure the sums in which they already stood indebted. In addition, rumours continued to circulate to the effect that Mr Frant had been addicted to play, and that he had lost large sums of money at cards and at dice in private houses.

‘Whoever killed him did the hangman a favour,’ Dansey said. ‘If Frant weren’t already dead, they’d have tried him for forgery and sent him to the gallows for uttering.’

At the time there was much speculation as to whether Mrs Frant had been privy to her husband’s schemes. Some found her doubly guilty by association, for was she not the wife of one partner and the niece of another? Not everyone agreed.

‘A man does not discuss his business dealings with his wife,’ Dansey argued. ‘No, she is guilty merely by association. The public prefers a living scapegoat, if at all possible.’

What made matters worse was that Mrs Frant had no one to speak in her defence. Mr Carswall had given her the shelter of his roof but he remained silent on this head and on all others. She was said to be suffering from a fever, her spirits quite overthrown by the double tragedy of her husband’s murder and the revelation of his crimes.

As for Charlie, he stumbled like an automaton through the days. I wondered that Mr Carswall did not remove him from the school. Boys are unpredictable creatures. I had expected his schoolfellows would bait him, that they would make him suffer for his father’s crimes. Instead, most of them left him alone. Indeed, when they did not ignore him, they handled him with a certain rough kindness. He looked ill, and they dealt with him as though he were. Edgar Allan rarely left his side. The young American treated his friend with a solicitude and a delicacy of sentiment which was unusual in one so young.

Delicacy of sentiment, however, was not a characteristic which could be attributed to either Morley or Quird. Nor was common decency. I came across them fighting with Allan and Frant in a corner of their schoolroom. Morley and Quird were so much older and so much heavier that it was not so much a fight as a massacre. For once, I intervened. I flogged Morley and Quird on the spot and ordered them to wait on me that evening, so that I might flog them again.

‘Are you sure you want to do that, sir?’ Morley asked softly when he and Quird appeared before me at the appointed time.

‘I shall beat you all the more if you don’t take that insolent smile off your face.’

‘It’s only, sir, that me and Quird happened to see you and Mr Dansey the other night.’

‘Quird and I, Morley, Quird and I. The pronoun is part of a compound nominative plural.’

‘Smoking under the trees, you were.’

‘Then be damned to you for a pair of snivelling, spying scrubs,’ I snarled, my rage boiling over. ‘And why were you not in bed, pray?’

Morley had the impudence to ignore my question. ‘And we saw you and him, sir, on other nights.’

I stared at him, my anger rapidly subsiding. A show of anger has its uses when you are dealing with boys, but ungovernable passion must always be deplored.

‘Bend over,’ I ordered.

He did not move. ‘Perhaps, sir, it is my duty to inform Mr Bransby. We must all listen to the voice of conscience. He abhors the practice of –’

‘You may tell Mr Bransby what you like,’ I said. ‘First, however, you will bend over and I shall thrash you as you’ve never been thrashed before.’

The smile vanished from Morley’s broad, malevolent face. ‘This is most unwise, sir, if I may say so.’

The words were measured, but his voice rose into a squeak at the end when I hit him a backhanded blow across the mouth. He tried to protest but I caught him by the throat, swung him round and flung him across the chair that served as our place of execution. He did not move. I dragged up his coat-tails and flogged him. There was no anger in it now: I was cold and deliberate. One could not let a boy take such a haughty tone. By the time I let him go he could hardly walk, and Quird had to half carry him away.

Nevertheless the incident left me shaken, though Morley had richly deserved his beating. I had never flogged a boy so brutally before, or given way to my passions. I wondered if the murder of Henry Frant had affected me in ways I had not suspected.

What I did not even begin to suspect until later was that Morley may have known Dansey better than I did, and that his meaning had been quite other than I had supposed.

Nine days after the murder, on Saturday the 4th December, I received a summons to Mr Bransby’s private room. He was not alone. Overflowing from an elbow chair beside the desk was the large, ungainly form of Mr Carswall. His daughter perched demurely on a sofa in front of the fire.

As I entered, Carswall glared up at me through tangled eyebrows and then down at the open watch in his hand. ‘You must make haste,’ he said. ‘Otherwise we shall not get back to town in daylight.’

Astonished, I looked from one man to the other.

‘You are to accompany Charles Frant to Mr Carswall’s,’ Bransby said. ‘His father is to be buried on Monday.’

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

‘I AM A bastard,’ Miss Carswall said to me on the Monday evening after Mr Frant’s funeral.

I was so shocked by her immodesty I did not know how to reply. I glanced at the door, fearing it might be open, that her words had been overheard. At the time Miss Carswall and I were alone in the drawing room of her father’s house in Margaret-street; Charlie had run upstairs to fetch a book.

She fixed me with her brown eyes. ‘Let us call things by their proper names. That is what I wished to tell you in Albemarle-street. The day when Charlie interrupted.’

‘It is of no significance,’ I said, feeling I must say something.

She stamped her foot. ‘Had you been a bastard yourself, you would know how foolish that sounds.’

‘I beg your pardon. I did not make my meaning clear. I did not mean that it was of no significance to you, or indeed in the general scheme of things. I – I meant merely that it was of no significance to me.’

‘You knew, sir, admit it. Someone had told you.’

Miss Carswall glared at me for a moment. She had the fair, almost translucent skin that so often goes with auburn hair. She looked captivating in a passion.

‘My papa does not choose to advertise the circumstances of my birth,’ she went on after a moment’s silence. ‘Which in itself has been a matter of some inconvenience to me. It can lead to situations in which people – that is to say – they may approach me under false pretences.’

‘You need not trouble yourself on my account, Miss Carswall,’ I said.

She studied the toes of her pretty little slippers. ‘I believe my mother was the daughter of a respectable farmer. I never knew her – she died before I was a year old.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be. When I was six, my father sent me to board at a seminary in Bath. I stayed there until I was fifteen, when I went to live with my cousin, Mrs Frant. Papa and Mr Frant were then on friendly terms, you see. Mr Frant was in America on the bank’s business, so there were just the three of us, Mrs Frant, little Charlie and me. I wish …’

‘What do you wish?’

‘I wish I could have stayed there. But my father’s wife died, so there was no longer an obstacle to my living with him. And he and Mr Frant had quarrelled, so it was not convenient for me to stay in Russell-square. So I came here.’ She spoke jerkily now, as though pumping the words from a deep reservoir of her being. ‘As a sort of companion. A sort of housekeeper. A sort of daughter. Or even – Ah, I scarcely know what. All those things and none of them. When my father brings his friends to the house, they do not know what I am. I do not know what I am.’ She broke off and sat down on the little sofa by the fire. Her bosom rose and fell in her agitation.

‘I am honoured you should take me into your confidence,’ I said softly.

She looked up at me. ‘I am glad the funeral is over. They always make me hippish. No one came, did they, no one but that American gentleman. You would not think it now but in his life Henry Frant had so many people proud to call him friend.’