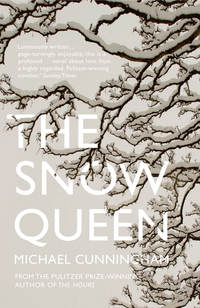

The Snow Queen

“I know,” Barrett says. “I know it’ll matter to you. But I think you should remember that it won’t, to her. Not in the same way.”

Barrett, bluff-chested, naked in graying water, is in particular possession of his pink-white, grandly mortified glow.

“I’m going to make some coffee,” Tyler says.

Barrett stands up in the tub, streaming bathwater, a hybrid of stocky robust manliness and plump little boy.

This peculiarity: Tyler is untroubled by the sight of Barrett emerging from his bathwater. It is, for mysterious reasons, only Barrett’s immersion that’s difficult for Tyler to witness.

Might that have to do with endangerment, and rescue? Duh.

Another peculiarity: Knowledge of one’s deeper motives, the sources of one’s peccadilloes and paranoias, doesn’t necessarily make much difference.

“I’m going to go to the shop,” Barrett says.

“Now?”

“I feel like being alone there.”

“It’s not like you don’t have your own room. I mean, am I crowding you?”

“Shut up. Okay?”

Tyler tosses Barrett a towel from the rack.

“It seems right, that the song is about snow,” Barrett says.

“It seemed right when I started it.”

“I know. I mean, it all seems right when you start it, it seems infinitely promising and inspired and great … I’m not trying to be profound, or anything.”

Tyler lingers for a final moment, to fully feel the charge. They do the eye thing, once more, for each other. It’s simple, it’s undramatic, there’s nothing moist or abashed, nothing actually ardent, going on, but they pass something back and forth. Call it recognition, though it’s more than that. It’s recognition, and it’s the mutual conjuring of their ghost brother, the third one who didn’t quite manage to be born, and so, being spectral—less than spectral, being never—is their medium, their twinship, their daemon; the boy (he’ll never grow past the pink-faced, holy gravitas of the cherubim) who is the two of them, combined.

Barrett dries off. The bathwater, now that he’s out of the tub, has turned from its initial, steaming clarity to a tepid murk, as it always does. Why does that happen? Is it soap residue, or Barrett residue—the sloughed-off outermost layer of city grime and deceased epidermis and (he can’t help thinking this) some measure of his essence, his little greeds and vanities, his self-admiration, his habit of sorrow, washed away, for now, with soap, left behind, to spiral down the drain.

He stares for a moment longer at his bathwater. It’s the usual water. It’s no different the morning after the night he’s seen something he can’t really have seen.

Why, exactly, would Tyler believe this was a good morning to return them to the story of their mother?

A time-snap: Their mother reclines on the sofa (which is here now, right here in their Bushwick living room), smoking, cheerfully bleary on a few old-fashioneds (Barrett likes her best when she drinks—it emphasizes her aspect of extravagant and knowing defeat; the wry, amused carelessness she lacks when sober, when she’s forced by too much clarity to remember that a life of regal disappointment, while painful, is also Chekhovian; grave, and rather grand). Barrett is nine. His mother looks at him with drink-sparked eyes, smiles knowingly, as if she’s got a pet leopard lying at her feet, and says, “You’re going to have to watch out for your older brother, you know.”

Barrett waits, mutely, sitting on the sofa’s edge, at the curve of his mother’s knees, for meaning to arrive. His mother takes a drag, a sip, a drag.

“Because, sweetheart,” she says, “let’s face it. Let’s be candid, can we be candid?”

Barrett acknowledges that they can. Wouldn’t anything other than total candor between a mother and her nine-year-old son be an aberration?

She says, “Your brother is a lovely boy. A lovely, lovely boy.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And you” (drag, sip) “are something else.”

Barrett blinks, damp-eyed with incipient dread. He is about to be told that he’s subservient to Tyler; that he’s the portly little quipster, the comic relief, while his older brother can slay a boar with a single arrow, split a tree with one caress of an axe.

She says, “Some magic has been granted to you. I’m damned if I know where it came from. But I knew it. I knew it right away. When you were born.”

Barrett keeps blinking back the tears he’s determined not to shed in front of her, though he wonders, with increasing urgency, what, exactly, she’s talking about.

“Tyler is popular,” she says. “Tyler is good-looking. Tyler can throw a football … well, he can throw it pretty far, and in the direction footballs are supposed to go.”

“I know,” Barrett says.

What strange impatience rises now to his mother’s face? Why does she look at him as if he were sycophantically eager, desperate to please some doddering aunt by pretending surprise over every twist in a story he’s known by heart, for years?

“Those whom the gods would destroy …” his mother says, blowing smoke up into the crystals of the modest dome-shaped chandelier that clings like an upside-down tiara to the living room ceiling. Barrett isn’t sure whether she can’t, or won’t, finish the line.

“Tyler is a good guy,” Barrett says, for no reason he can name, beyond the fact that it seems he has to say something.

His mother speaks upward, toward the chandelier. She says, “My point exactly.”

This will all start making sense. It will, soon. The square crystals of the chandelier, worried by the electric fan, each crystal the size of a sugar cube, put out their modest, prismed spasms of light.

His mother says, “You may need to help him out, a little. Later. Not now. He’s fine, now. He’s cock o’ the walk.”

Cock o’ the walk. A virtue?

She says, “I just want you to, well … remember this conversation we’re having. Years from now. Remember that your brother may need help from you. He may need a kind of help you can’t possibly imagine, at the age of ten.”

“I’m nine,” Barrett reminds her.

Almost thirty years later, having arrived at the future to which his mother was referring, Barrett pulls the plug on the bathtub. There’s the familiar sound of water being sucked away. It’s a morning like any other, except …

The vision is the first event of any consequence, in how many years, about which Barrett hasn’t told Tyler; which he continues not mentioning to Tyler. Barrett has never, since he was a kid, been alone with a secret.

He has, of course, never kept a secret quite like this.

He’ll tell Tyler, he will, but not now, not yet. Barrett isn’t ready for Tyler’s skepticism, or his valiant efforts at belief. He’s really and truly not ready for Tyler to be worried about him. He can’t bring himself to be another cause for concern, not with Beth getting neither better nor worse.

A terrible thing: Barrett finds sometimes that he wants Beth either to recover or die.

The endless waiting, the uncertainty (higher white-cell count last week, that’s good, but the tumors on her liver are neither growing nor shrinking, that’s not so good), may be worse than grieving.

A surprise: There’s no one driving the bus. There are five different doctors now, none of them actually in charge, and sometimes their stories don’t match up. They make efforts, they’re not bad doctors (except for Scary Steve, the chemo guy), they’re not negligent, they try this and they try that, but Barrett (and Tyler, and probably Beth, though she’s never talked about it) had imagined a warrior, someone kind and august, someone who’d be sure. Barrett had not expected this disorganized squadron—all upsettingly young, except for Big Betty—who know the language of healing, who reel off seven-syllable terms (tending to forget, or to disregard, the fact that the words are incomprehensible to anyone who isn’t a doctor), who can operate the machinery, but who, purely and simply, don’t know what’s going to work, or what’s going to happen.

Barrett can keep this one about the celestial light private, for a while. It’s not an announcement Tyler needs to receive.

Barrett has, naturally enough, Googled every possible malady (torn retina, brain tumor, epilepsy, psychotic break) that’s presaged by a vision of light. Nothing quite fits.

Although he’s seen something extraordinary, and hopes it isn’t the precursor of a mortal ailment he failed to find on the Internet, he has not been instructed, he has not been transformed, there’s been no message or command, he is exactly who he was last night.

However. The question arises: Who was he last night? Has he in fact been altered in some subtle way, or has he simply been rendered more conscious of the particulars of his own ongoing condition? It’s a hard one to answer.

An answer might account for how and why Barrett and Tyler have lived so randomly (they, the National Merit boys—well, Barrett; Tyler was a runner-up—club presidents, Tyler crowned king of the fucking prom); why they happened to meet Liz when he and Tyler went, as each other’s date, to what has lived on as the Worst Party in History; why the three of them escaped the party and passed midnight together in some divey Irish pub; why Liz would eventually introduce Beth, newly arrived from Chicago; Beth who in no way resembles any of Tyler’s previous girlfriends, and with whom he’d fallen so immediately in love that he resembled some captive animal, fed for years on what its keepers believed to be its natural diet and then suddenly, one day, by accident, given what it actually ate, in the wild.

None of it has ever felt predetermined. It’s sequential, but not exactly orderly. It’s all been going to this party instead of that one, happening to meet someone who knew someone who by the evening’s end had fucked you in a doorway on Tenth Avenue or given you K for the first time or said something shockingly kind, out of nowhere, and then gone away forever, promising to call; or, with an equally haphazard aspect, happening to meet someone who’ll change everything, forever.

And now it’s a Tuesday in November. Barrett has gone for his morning run, had his morning bath. He’s going to work. What is there to do but what he always does? He’ll sell the wares (it’ll be slow today, because of the weather). He’ll continue with his exercise regimen and the no-carbs diet that will not make any difference to Andrew but will, might, help Barrett feel more agile and tragic, less like a badger besotted by a lion cub.

Will he see the light again? What if he doesn’t? Maybe he’ll grow old as a tale-teller who once saw something inexplicable; a UFO person, a Bigfoot person, a codger who experienced a brief, wondrous sighting of something inexplicable, and then went on about the business of getting older; who is part of the ongoing subhistory of crackpots and delusionals, the legions of geezers who know what they saw, decades ago, and if you don’t believe it, young one, that’s all right, maybe one day you, too, will see something you can’t explain, and then, well, then I guess you’ll know.

Beth is looking for something.

The trouble: She can’t seem to remember what it is.

She knows this much: She’s been careless, she’s misplaced … what? Something that matters, something that must be found, because … it’s needed. Because she’ll be held accountable when its absence is noticed.

She’s searching a house, although she’s not sure if it (what?) is here. It seems possible. Because she’s been in this house before. She recognizes it, or remembers it, in the way she remembers the houses of her childhood. The house multiplies into the houses in which she lived, variously, until she went away to college. There’s the gray-and-white-striped wallpaper of the house in Evanston, the French doors from Winnetka (were they really this narrow?), the crown molding from the second house in Winnetka (was it wound in these white plaster leaves, was there this suggestion of wise but astonished eyes, peering through the leaves?).

They’ll be back soon. Somebody will be back soon. Someone stern. The harder Beth searches, though, the less sense she has of what it is she’s lost. It’s small, isn’t it? Spherical? Is it too small to be visible? It might be. But that doesn’t alter the urgency of its discovery.

She’s the girl in the fairy tale, told to turn snow into gold by morning.

She can’t do that, of course she can’t, but there seems to be snow everywhere, it’s falling from the ceiling, snowdrifts shimmer in the corners. She remembers dreaming about searching through a house, when what she needs to do is turn snow into gold, how could she have forgotten …

She looks down at her feet. Although the floor is dusted with snow, she can see that she’s standing on a door, a trapdoor, contiguous with the floorboards, made apparent only by its pair of brass hinges and its tiny brass knob, no bigger than a gumball.

Her mother gives her a penny for a gumball machine outside the A&P. She doesn’t know how to tell her mother that one of the gumballs is poisoned, no one should put a penny into this machine, but her mother is so delighted by Beth’s delight, she’s got to put the penny in, hasn’t she?

There’s a trapdoor at her feet, in the sidewalk in front of the A&P. It’s snowing here, too.

Her mother urges her to put the penny into the slot. Beth can hear laughter, coming from underneath the door.

An annihilating force, a swirling orb of malevolence, is what’s laughing under the trapdoor. Beth knows this to be true. Is the door beginning, ever so slowly, to open?

She’s holding the penny. Her mother says, “Put it in.” It comes to her that the penny is what she thought she was searching for. She seems to have found it, by accident.

Tyler sits in the kitchen, sipping coffee and doing one last line. He’s still wearing the boxer shorts, and has put on Barrett’s old Yale sweatshirt, its grimacing bulldog faded, by now, from red to a faint, candyish pink. Tyler sits at the table Beth found on the street, cloudy gray Formica that’s chipped away in one corner, a ragged-edged gap the shape of the state of Idaho. When this table was new, people expected domed cities to rise on the ocean floor. They believed that they lived on the brink of a holy and ecstatic conjuring of metal and glass and silent, rubberized speed.

The world is older now. It can, at times, seem very old indeed.

They will not reelect George Bush. They cannot reelect George Bush.

Tyler pushes the thought out of his mind. It would be foolish to spend this lambent early hour obsessing. He’s got a song to finish.

So as not to awaken Beth, he leaves his guitar in the corner. He whisper-sings, a cappella, the verse he wrote last night.

To walk the frozen halls at night

To find you on your throne of ice

To melt this sliver in my heart

Oh, that’s not what I came for

No, that’s not what I came for.

Hmm. It’s crap, is it?

The trouble is …

The trouble is he’s determined to write a wedding song that won’t be all treacle and devotion, but won’t be cool or calm, either. How, exactly, do you write a song for a dying bride? How do you account for love and mortality (the real thing, not some till-death-do-us-part throwaway) without morbidity?

It needs to be a serious song. Or, rather, it needs not to be a frivolous song.

The melody will help. Please, let the melody help. This time, though, the lyrics need to come first. Once the lyrics feel right (once they feel less wrong), he’ll lay them over … a minimal tune, something simple and direct, not childish of course but possessed of a childlike, beginner’s earnestness, a beginner’s innocence of tricks. It should be all major chords, with one minor, at the end of the bridge—that single jolt of gravitas; that moment when the lyrics’ romantic solemnity departs from the contrast of its upbeat chords and matches—fleetingly—a darkness in the music itself. The song should reside in the general vicinity of Dylan, of the Velvet Underground. It should not be faux-Dylan, not fake Lou Reed; it should be original (original, naturally; preferably unprecedented; preferably tinged with genius), but it helps, it helps a little, to aim in a general direction. Dylan’s righteous banishment of sentimentality, Reed’s ability to mingle passion with irony.

The melody should have … a shimmering honesty, it should be egoless, no Hey, I can really play this guitar, do you get that? Because the song is an unvarnished love-shout, an implorement tinged with … anger? Something like anger, but the anger of a philosopher, the anger of a poet, an anger directed at the transience of the world, at its heartbreaking beauty that collides constantly with our awareness of the fact that everything gets taken away; that we’re being shown marvels but reminded, always, that they don’t belong to us, they’re sultan’s treasures, we’re lucky (we’re expected to feel lucky) to have been invited to see them at all.

And there’s this, as well. The song has to be infused with … if not anything as banal as hope, an assertion of an ardency that can, if this is humanly possible (and the song must insist that it is), follow the bride in her journey to the netherworld, abide there with her. It has to be a song in which a husband and singer declares himself to be not only a woman’s life-mate, but her death-mate as well, although he, helpless, unconsulted, will keep on living.

Good luck with that one.

He pours himself more coffee, draws out a final, really final, line on the tabletop. Maybe he’s just not … awake enough to be gifted. Maybe one day, why not today, he’ll bust out of his lifelong drowse.

Would “shiver” be better than “sliver”? To melt this shiver in my heart?

No. It wouldn’t.

That repetition at the end—is it forceful or cheap?

Should he try for a half-rhyme with “heart”? Is it too sentimental to use the word “heart” at all?

He needs a looser association. He needs something that implies a man who wants the ice shard to remain in his chest, who’s learned to love the sensation of being pierced.

To walk the frozen halls at night

To find you on your throne of ice

Maybe it’s not as bad as it sounds this early in the morning. That’s a possibility.

But still. If Tyler were the real thing, if he were meant to do this, wouldn’t he have more confidence? Wouldn’t he feel … guided, somehow?

Never mind that he’s forty-three, and still playing in a bar.

He will not come to his senses. That’s the siren song of advancing age. He can’t, he won’t, deny the snag in his heart (there’s that word again). He can feel it, an undercurrent in his bloodstream, this urge that’s utterly his own. No one ever said to him, why don’t you use your degree in political science to write songs, why don’t you blow the modest inheritance your mother left by sitting in ever-smaller rooms, strumming a guitar. It’s his open secret, the self inside the self, secret because he believes he knows within himself a brilliance, or at least a penetrating clarity, that hasn’t come out yet. He’s still producing approximations, and it vexes him that most people (not Beth, not Barrett, just everybody else) see him as a sad case, a middle-aged bar singer (no, make that a middle-aged bartender, who’s permitted by the owner to sing on Friday and Saturday nights), when he knows (he knows) that he’s still nascent, no prodigy of course, but the music and poetry move slowly in him, great songs hover over his head, and there are moments, real moments, when he feels so certain he can reach them, he can almost literally pull them out of the air, and he tries, lord how he tries, but what he grabs hold of is never quite it.

Fail. Try again. Fail better. Right?

He sings the first two lines again, softly, to himself. He hopes they’ll open into … something. Something magical, and obscurely on target, and … good.

To walk the frozen halls at night

To find you on your throne of ice

He sings quietly in the kitchen, with its faint gassy smell and its pale blue walls (they must, once, have been aquamarine), its tacked-up photographs of Burroughs and Bowie and Dylan, and (Beth’s) Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor. If he can write a beautiful song for Beth, if he can sing it to her at their wedding and know that it’s a proper testament—a true gift, not just another near miss, another nice try, but a song that lands, that lances, that’s gentle but faceted, gleaming, gem-hard …

Give it one more go, then.

He starts singing again, as Beth dreams in the next room. He sings quietly to his lover, his bride to be, his dying girl, the girl for whom this song and, probably, really, all the songs are meant. He sings into the brightening air of the room.

Barrett has gotten dressed. The tight (too tight? fuck it—if you present yourself as a beauty, people tend to believe you) wool pants, the Clash T-shirt (worn down to pearl-gray translucence), the ostentatiously ragged sweater that drapes limp and indolent almost to his knees.

Here he is, bathed, hair-gelled, dressed for the day. Here’s his reflection in his bedroom mirror, here’s the room in which he currently resides: Shinto-inspired, just a mattress and a low table, the walls and floor painted white, Barrett’s private sanctuary from the funky-junk museum that is the rest of Tyler and Beth’s apartment.

He takes out his cell phone. Liz’s phone will be turned off, of course, but he should tell her he’s going to open the shop this morning.

“Hey, it’s Liz, leave a message.”

He’s still surprised, sometimes, by the clipped force of her voice, when it transmits unaccompanied by her animated, rather off-kilter face (she’s one of those women who insists, successfully, on her own beauty—Barrett has learned from her; on the assertion that a hooked jut of nose and a wide, thin-lipped mouth is, must be, added to the list of desirable features), the careless gray tangle of her hair.

Barrett speaks into (onto?) her voice mail.

“Hi. I’m going in early, just to lurk around, so if you and Andrew want to stay snuggled up, go ahead. I’ll open. And it’s not like there’s going to be any customers on a day like this. Bye.”

Andrew. The most ideal being among Barrett’s inner population; graceful and inscrutable as a figure from the Parthenon friezes; Barrett’s singular experience of the godly. Andrew is as close as Barrett has come to a sense of divine presence in the world.

A minor epiphany circles his head like a persistent fly. Did his most recent boyfriend leave so casually because he sensed Barrett’s fixation on Andrew, which Barrett never, ever, mentioned? Is it possible that the departed boy perceived himself as an imitation, of sorts; as the most possessable version of Andrew’s offhand, no-big-deal beauty; Andrew who will do, for now and possibly forever, as the most persuasive living evidence of God’s genius, coupled with God’s inscrutable propensity for sculpting some of the clay with a degree of attention to the symmetries and precisions He (She?) withholds from most of the population at large?

No. Probably not. The guy wasn’t, frankly, a particularly subtle or intuitive thinker, and Barrett’s devotion to Andrew carries no hint of actual possibility. Barrett adores Andrew the way one might a Phidias Apollo. You don’t expect a marble sculpture to step down off its museum pedestal and take you in its arms. No one dumps a lover because the lover is besotted by art. Right?

Who doesn’t want—who doesn’t need—a moon at which to marvel, a fabled city of glass and gold on the far side of the ocean? Who would insist that his corporeal lover—the guy in his bed, the man who forgets to throw his used Kleenexes away, who used the last of the coffee before he left for work—be the moon or the city?