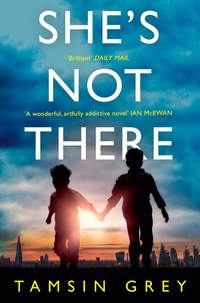

She’s Not There

‘You know …’ He looked out into the sunny street and then down at his watch. The two women gazed at him. ‘Maybe I have got time to play something quick. If – if that’s what you’d like.’

‘Yes!’ Embarrassed by her own delight, Pat clapped her hand over her mouth again.

4

On Monday morning Jonah woke up trying to say something. He was making tiny croaking noises, trying to get the words out, and his sheet was all tangled up in his legs. The room was full of sunlight, because of the fallen-down curtain, and outside the birds were screeching like crazy.

He sat up, kicking the sheet away, and looked over at the clock: 04.37. The sun must have just that minute risen, or rather Earth had just tipped far enough towards it. He was naked. It had been so hot in the night he’d pulled off his vest and wriggled out of his pyjama bottoms. His dream was like a word on the tip of his tongue. The birds had calmed down, but a dog was barking, and now there was a man talking, down in the street, right under the wide open window.

Jonah lay back down and tried to remember what it was he wanted to say, but the strange, hissing voice outside kept telling someone to shut their mouth. No one else was saying anything, so the man was either talking to himself, or talking into his phone. His tongue found his loose tooth, and waggled it. ‘This tooth is movious,’ Lucy, his mother, had said at bedtime, in her Zambian doctor voice, her finger pushing it gently. ‘It will be coming out on Wednesday.’

He rolled onto his side and looked down at the book she’d read from at bedtime, lying open on the floor, surrounded by clothes. It was a poetry book by a man called Edward Lear. She’d read them ‘The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò’, a very sad story about a tiny little man with an enormous head. It was her favourite. He and Raff preferred ‘The Duck and the Kangaroo’. As he gazed at the picture of the Lady Jingly Jones, surrounded by her hens, telling the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò to go away, he remembered his feeling, as she read, that his mother was a stranger, lost in an unknown world. Such a weird feeling; difficult to explain.

He tugged at his tooth. He’d made a bet with her – £1 it would come out before Wednesday – which he was sure he would win. His eyes travelled up to his cloud poster. The clouds were grouped into families and species. His favourite was Stratocumulus castellanus. Next to the cloud poster were Raff’s three athlete posters: Usain Bolt, Mo Farah and Oscar Pistorius. Raff was a really good runner. Which reminded him … Which reminds me, Mayo. No, not Mayo, he’d started calling her Lucy, to be more grown-up. Which reminds me, Lucy. What was it that he needed to tell her? He noticed that the top left corner of the Oscar Pistorius poster was curled over, detached from its lump of Blu-tack. Oh yes, Sports Day. That was it. Sports Day had been cancelled the week before, because of all the rain, but everyone had been so disappointed that Mr Mann had decided they could squeeze in a shortened version this Thursday. There had been a letter about it. Probably still in his school bag.

He sat up again, to see the clock. 04.40, a mirror number. He climbed down the ladder past Raff’s sleeping head, pulled on his boxers and crept out of the room. It was only three and a half steps across the landing and into Lucy’s bedroom. Her curtains were drawn tight, so it was dark and the warm air smelt of her grown-up body. There were clothes all over the floor. Jonah stood on a coat hanger and said ‘Ouch’, but quietly. He reached her bed and climbed onto it, fumbling for the sheet and pulling it over him. The smell of her was stronger, more secret, and he rolled across to snuggle up. But she wasn’t there.

Jonah rolled to the far side of the bed and looked at the crowd of things on Lucy’s bedside table. Her Tibetan bells alarm clock, a wine glass with a smudge of lipstick on it, the mugs he’d brought her tea in, the days she’d stayed in bed. The card with the X on it was leaning against one of the mugs, and he reached for it. People usually did a few Xs, little ones, under their signature. This single X filled the whole card. One long kiss, then. He pictured his father Roland’s face, with hopeful lips. The card had come with the flowers, was it Thursday or Friday? They were a mixture of roses and lilies, the roses red and fat like cabbages, and the lilies all creamy and freckled with gold. He’d brought them up to her, and she’d taken the card and told him to put the flowers in a vase. Which he had done, but without any water, so they had died. Jonah put the card back down and wobbled his tooth, seeing Roland’s face again – his anxious frown, his sticky-out ears. They hadn’t been to visit him for ages. Maybe he would ask if he could phone him up. He would tell him about the tooth bet first. Then he’d check about the flowers.

He rolled over again, back to the near side of the bed, sat up and swung his feet down to the floor. By the skirting board was her big tub of coconut oil, without the lid. The oil was thick and white, like wax, and there were three indents where her fingers had dug into it. It would come out in white lumps, but then, as she rubbed it into her skin, it would melt into transparent liquid. He crouched down and put three of his own fingers in the holes. They were wet and oozy: the wax was melting because it was so warm. He wiped his fingers on the sheet and went to see if she was in the bathroom.

His pupils, large from the darkness, had to quickly shrink again, because light was flooding in through the open window, bouncing between the mirrors and the taps and the water in the bath. The bathwater was green and shimmery, with a few black squiggly hairs floating on the surface. Jonah put his hand in and the light on the ceiling broke into ripples. The water was lukewarm and very oily, and when he pulled out his hand one of the hairs was coiled around his fingers. He got some toilet paper and wiped it off, and then he put the paper down the toilet. There was wee in the toilet, very dark, smelly wee, and Jonah flushed it, before leaving the bathroom and going to stand at the top of the stairs. He looked down and his heart beat faster, because the front door was open.

Jonah padded downstairs and out into the street. Under his feet the pavement was still cool, but the light was blinding. Their house was on a corner. The front door was on Southway Street, but the sitting-room window and the boys’ bedroom window were on the other side of the house. Jonah looked that way first, towards Wanless Road, which was still in shadow. On the far side of the road, the metal blinds were still down over the four shops, one of them spray-painted with the word ‘Pussy’. A wheelie bin, its lid thrown open, balanced precariously on the kerb. Then he turned his head and shaded his eyes with his hand to look down sun-drenched Southway Street. The pretty houses looked like they still had their eyes closed. Only the light moved, glinting on the parked cars and the netted metal cages around the spindly white trees.

Jonah turned and walked around the corner into Wanless Road. It was wider than Southway Street, with no trees, and wheelie bins were parked at intervals along the pavements, like Daleks. The Broken House was next to theirs, but there was a gap in between. It was older than all the terraced houses, and had been much bigger and grander, all on its own in its garden. They could see right into it from Lucy’s bedroom window, but from here it was hidden by high, joined-together boards, covered in places by a tumbling passionflower, and dotted with ‘Keep Out’ signs. In fact, it was easy to get in. One of the boards had come loose and you could push it open like a door and slip inside.

Jonah walked through the stillness like he was the only thing left alive, dragging his fingers along the splintery boards. The loose board had been left ajar, and he peered through. The nettles had grown as high as his chest. The Broken House looked back at him, like a sad old horse. It was a long time since he’d been in there. As he turned away, with a start, he noticed Violet.

The fox was standing, still as a statue, on the bonnet of a filthy white van. Their eyes met, and although he knew her well, he felt shy of her, almost scared. He said, ‘Hello, Violet’, trying to sound normal, but his voice croaked, and all of a sudden she leapt onto the pavement and flitted into the Broken House’s tangled garden. Animals can sense your fear, he remembered his mother saying, they can smell it, and it makes them frightened. He looked after the fox for a moment, and then at the white marks her scrabbling paws had left in the van’s thick grey dirt. There was a V-shape, and two long scribbles, like a signature. He turned to walk back to their house – which was when he saw the Raggedy Man.

The Raggedy Man was standing against the wall of the squatters’ house; like Violet, so still that Jonah hadn’t noticed him. His feet were turned in and his arms hung down like coat sleeves. ‘Remember, he was a boy like you once,’ Jonah heard Lucy say, but he quickened his step, crossing his arms over his naked chest. The Raggedy Man was tall and black and gnarled like a tree, growing out of his filthy, raggedy pink tracksuit. He never said anything, ever, not a single word. Jonah found himself saying, A boy like you once, over and over in his head, as his feet padded quickly along the pavement. He turned into Southway Street and, from the corner of his eye, he saw the Raggedy Man put his hand in the pocket of his tracksuit bottoms and pull something out. Then his arm snapped out straight, the hand splayed open … offering something? Jonah hesitated on his doorstep. There was an object glinting in the Raggedy Man’s palm. A coin? He darted a look up at the grizzly face. The huge, angry eyes stared back at him. He looked away quickly, scurried inside and closed the door.

5

He had only been out for a few seconds, but it felt like he’d come back from another world. Standing in the familiar jumble of the hallway, he could smell their wet swimming things, still in the bag. They’d gone to the Lido the day before, Sunday, on their bikes, early, to avoid the queue. Lucy loved to swim, but had sat on the edge, her wild hair crammed under a big straw hat, gold locket at her throat, her body wrapped in her enormous red sarong. As he’d glided like a manta ray above the slime-smeared floor of the pool, he had looked up and seen her strong brown feet dangling in the water. Why won’t you come in? he had asked her silently. Her toes had rings on them – gold, like the locket – and her toenails matched the sarong.

Her red umbrella was leaning against the wall. He and Raff had taken it to school the day it rained. Next to the umbrella was the stepladder, which she must have pulled out from the cupboard under the stairs, as a reminder to get the curtain in their room back on its rail. Under the ladder was the can of petrol that, weeks and weeks ago, they’d walked all the way to the service station on the main road to get. They’d taken it on the bus, all the way across south London, to where they’d had to abandon the car the evening before. They’d been too late, though – the car had been towed away, so they’d brought the petrol back home. Getting the car back cost lots of money, which they didn’t have. They didn’t really need a car anyway. Next to the petrol was a pile of shoes, among which, Jonah was relieved to see, were her clogs. She must be here after all. He turned and pushed open the sitting-room door.

She wasn’t there. Jonah looked down at her yoga mat, lying like a green lake amidst a jumble of Lego, nunchucks and cheese on toast remains. Part of Raff’s Ben 10 jigsaw encroached upon the mat, like a jetty. He looked up. Through the sitting-room window, he saw the open-lidded wheelie bin balancing on the kerb.

She’d been burning incense in the kitchen, but the smell of the bin was stronger than ever. They hadn’t emptied it for days – maybe weeks. Lucy had been ill for quite a while, off and on. Washing-up was stacked high on every surface, and the dirty clothes they’d collected up to put in the machine lay in piles all over the floor. He kicked through the clothes and went through into the tiny conservatory (if you could call it that), just big enough for the table, the three ordinary chairs and Raff’s old Tripp Trapp ladder chair. The dead flowers had shed some more petals, onto the drawings they’d done of them when they’d got back from the Lido. Lucy had said she didn’t mind they were dead. ‘I prefer them when they get like this. Much more interesting.’ Maybe she had just wanted to make him feel better about them, but she had carried on, her voice low and dreamy. ‘The intricate husks of them, like skeletons, on their way to dust.’ Jonah traced the line she had drawn, a fragile curl of dried-out lily petal. Her book was on the table, too, the book she’d been reading for weeks, even though it was very thin. There was a picture of a mask on the cover, an African-looking mask, with feathers and round empty eyeholes. Ants were crawling over the book and the drawings, and up and down the glass jug she’d made the orange squash in. There was a layer of black on the remaining inch of orange liquid: a floating blanket of drowned ants. The dead ants made him think of their holiday in the house with the swimming pool, and Lucy rescuing insects from the pool all day, using a net on a long pole. It was in France, the house. The Martins had taken them, as a treat, after Angry Saturday, and Roland getting sent to prison.

There were two new things on the table: a green wine bottle, empty; and a yellow mango, fat and ripe. The bottle was green, and the label was white, very white, with a grey drawing of jagged hilltops poking out of a sea of cloud like shark fins. The cloud was stratus, which wasn’t all that interesting to look at from below, but from above it was all misty and rolling. Jonah picked up the mango. Its skin squished under his fingers. ‘A Chaunsa,’ he whispered. The King of Mangoes. The Green Shop Man had introduced them to Chaunsas, which grow in Pakistan, but only in July. Last year, the Green Shop Man had given her three of them, as a present.

Near the edge of the table were three little heaps. When he looked closer, he saw that they were made of the shavings from the coloured drawing pencils, mixed with crumbs and his and Raff’s fingernails. She’d cut their nails after they’d done the drawings, and it had been about time; they’d been long and ragged and dirty, like witches’ fingernails. The heaps were like tiny pyramids. He touched one of them gently, imagining her sitting at the table after she’d put them to bed, all alone, with her too-thick lipstick on, slowly pushing the fingernails and the pencil shavings and the crumbs together with her fingers. Then maybe her phone had rung, and it had been Dora Martin. And then maybe Dora had come round with the bottle of wine.

It would be good if Dora had come. She hadn’t come for ages, and they hadn’t been to the Martins’ house for a while either. They’re still our friends, though. Aren’t they? He noticed how much he talked to her in his head, instead of just having his own thoughts. Did other children do that, to their mothers, or maybe their fathers?

There were no glasses on the table. He looked over at the pile of things on the draining board, and then remembered the wine glass by Lucy’s bed, with the smudge of lipstick. If there was only that one wine glass, then maybe she had decided to pop to the Green Shop and buy a whole bottle of wine to drink on her own. Taken the last glass of it up to bed with her. He looked at the label again. Such a beautiful, soft drawing, and the words Cloudy Bay, in such fine, thin letters, with lots of space in between. It didn’t look like the kind of wine you could get in the Green Shop. Then he saw that a steady stream of ants was heading down into the jug, despite the blanket of corpses. He thought about trying to divert them from their death, but the only thing he could think of would be to empty the jug and wash it, and the sink was too full of plates and pots.

Jonah looked up at the calendar. Yoga Poses 2013. The pose for July was Ustrasana, or Camel, and there was a picture of a woman, on her knees, arching backwards. The pages of previous calendars had always got filled with Lucy’s scrawls, but this one had stayed very bare and clean. He stepped closer, gazing up at the four and a half rows of squares, thinking how each square was a complete turn of the planet on its axis. The first two weeks were all empty. Then, in the middle of the third row, Wednesday the 17th, she’d written two letters, S and D. An acronym. For the rained-off Sports Day. There was a squiggly word beginning with C on the 18th, and then, on the fourth row, she had circled the 26th, and written three letters, P, E and D, in blobby brown felt-tip. PED. Trying to think what they might stand for, he reached up to take the calendar off its nail, and laid it on the table. Using the dark blue drawing pencil, he crossed out the cancelled SD, and wrote a new one in Thursday, the 25th. He thought for a moment. She hadn’t put ‘Haredale’s Got Talent’ on the calendar, even though Raff had been talking about nothing else for weeks. He wrote in HGT, right under SD. A busy day. He paused, and then went over the letters again, because the blue pencil didn’t come out that well on the shiny calendar paper.

Jonah put the pencil down, yawned and looked at the kitchen clock. 5.25. Where had she gone, so early? He turned and tried the back door. It wasn’t locked. Roland used to tell her off about not locking the back door. The backyard had a concrete floor, with brick walls on all three sides, the Broken House rising up behind the far wall. In the middle of the concrete floor was the brown corduroy cushion she’d been sitting on the day before. Yellow-flowering weeds were sprouting from the cracks in the concrete and from between the bricks. Lucy’s plant pots were sprouting weeds too, as well as the things she’d planted. Her dirt-covered trowel was resting against the wall. Her bicycle, which was a heavy, olden-days one, but painted gold, was gleaming against the back wall. Both the tyres were flat and weeds were growing through the spokes of the wheels. It was all looking very beautiful. He saw the watering can, and wondered if Lucy had watered the pots before she went.

A movement made him jump and look up. The fox had appeared on top of the back wall. Again their eyes met, and again he felt scared of her.

His heart banging, he cleared his throat. ‘Violet, are you following me this morning?’

He had tried to sound calm and amused, but his voice sounded thin and silly against the silence. ‘Fear is like a magnet,’ he heard Lucy say. ‘It can actually make bad things happen.’ He wondered if the Raggedy Man was still standing outside, waiting to give him the coin. He turned away from the fox, trying to stop his heart from thudding, and stared at the dip Lucy’s bottom had left in the corduroy cushion. He remembered the loops and the lines and the spatters, blue-black ink on the sunlit white page.

Brighter today.

That’s what she’d written, sitting on the corduroy cushion. He’d squeezed onto her lap, feeling her bosoms squishing against his back, and looked down at the shape of the words. Then a breeze had lifted the pages, and they had fluttered and batted against each other, all covered in her squiggly writing. And she’d reached forward with her dry, brown hand and flipped the book closed.

He checked the pots. They hadn’t been watered but under the surface the soil was still quite moist from all the rain the week before. In the biggest pot, which had honeysuckle growing out of it, and also delphiniums, there was something red and shiny sunk into the soil. A particular red. Definitely an object he’d seen before. A toy? One of his and Raff’s old cars? His fingers closed around it. Not a car. Not a toy, even. He pulled it out, and something caught in his throat, because it was a mobile phone, just like Lucy’s, a snap-shut Nokia. It probably was Lucy’s. But why would Lucy bury her phone in a flowerpot? His heart banging again, he wiped it on his boxers, but it left a dirty mark, so he shook it to get the rest of the dirt off it, and it came apart. The back of it and the battery plopped back into the soil. He retrieved them and carried the three parts of the phone back into the house. He laid them out on the table, and fetched a tea towel to wipe them properly clean, before clicking them back together.

It was her phone. It had to be. No one else had those Nokias any more. He pressed the ‘On’ button. There was a bleep, and the screen lit up. It was showing a very low battery, but it seemed to be working fine. After a few seconds there was another bleep, and a missed call popped upon the screen. DORA. So she had phoned, and maybe she had come round with the wine. The last time they’d been to the Martins’ must be the afternoon they’d taken Dylan round to mate with Elsie. Weeks ago. The phone bleeped again, and died. He weighed it in his hand, wondering where the charger might be, and remembering that chilly afternoon in the Martins’ garden, watching the rabbits.

The charger wasn’t in any of the wall sockets in the kitchen, and it wasn’t in the socket in the hall. In the hall he looked at Lucy’s clogs again. They were wooden clogs, very old, kind of chewed looking, but so comfortable, Lucy said. They were the only shoes she’d worn for weeks. He put his own feet into them, remembering seeing her red toenails through the water. His feet would be as big as hers soon. DORA. The word danced in his head. Maybe they would go round to the Martins’ after school. It would be nice to see the rabbits. And Saviour. He saw Saviour’s warm brown eyes, and heard his friendly, cockney voice. Fancy giving me a hand with the cooking?

He stepped out of the clogs and went upstairs. The charger wasn’t in the socket on the landing. Back in Lucy’s room, it was still quite dark and, instead of continuing his search, he found himself getting back into her bed, half expecting her to be there after all. She wasn’t. Where have you gone, silly Mayo? No, silly Lucy. He closed his eyes, and saw Dora, lying by the pool at the French holiday house, while Lucy, in just her bikini bottoms, walked up and down with her net. ‘Nice to get away from it all!’ Dora’s cheerful voice, her sunglasses, her long, thin body covered against the sun. ‘Nice to get away from it all!’ She’d kept saying it, all the way through the holiday, as if … As if what? He rolled onto his side, seeing Lucy’s net full of wet insects, her bosoms and her concentrating face as she tipped them out onto the paving stones; and got that weird feeling again, the one he got when she was reading the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò poem. That she was separate from him, different, a stranger; and it wasn’t just her grown-upness, or her femaleness, or her Africanness, which came and went with her mood. He pictured the three tiny pyramids on the kitchen table; and then the single, glinting disc on the Raggedy Man’s palm; the stepladder, the red umbrella, the scribble Violet’s paws made in the filth on the white van: and then he must have fallen asleep, because the next thing that happened was the ringing of the Tibetan bells.

6

The bells were a lovely sound. Jonah listened with his eyes closed, imagining the monks in their monastery in the misty mountains. Then Raff came running in, like a tornado.

‘There’s some guy swearing his head off in the street! You got to hear him, fam!’

Jonah opened his eyes and watched his little brother scamper around the bed, holding up his pyjama bottoms, which had lost their elastic. He realised he was still clutching the red phone, and put it down next to the lipsticky wine glass.

‘What’s that? Where’s Mayo? Why have you got her phone?’ One of Raff’s cornrows had started to come out. ‘Anyway, come on, you got to hurry. You seriously got to hear this!’