The Gentry: Stories of the English

Statistics can only be the roughest of informed guesses. Nevertheless, through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries there is no doubt that the economic and social structures of England underwent the deepest of transformations and the great beneficiaries of this double revolution – the failure of the magnates and then the failure of the crown – were the gentry. Their landholding rose from 20 per cent in the Middle Ages to something like half the country by the middle of the seventeenth century. The result was that where the crown, the church and the great lords had ruled medieval England, the great lords and the gentry came to rule early modern England.

This is the fluid and difficult environment in which the Throckmortons found themselves in the 1530s and where the Thynnes rode to riches and significance. Any number of sixteenth-century ‘new men’ understood the lesson promulgated by the old and cynical Tudor statesman William Paulet, Marquess of Winchester. When asked at the end of his career how he had managed to survive for thirty years at the centre of power, through so many reigns and changes, he said, ‘Ortus sum ex salice, non ex quercu, I was made of the plyable Willow, not of the stubborn Oak.’2 The heart of survival: pliancy.

It would be a mistake to make the focus of this history only the pain and struggle of survival in a challenging world. Tudor England was beautiful. Nowhere else in Europe was as green as England and every foreign visitor remarked on it – the thickness of the overhanging trees, the day-long spread of pasture as you rode across country. It was a world of beef and sheep. To keep the fertility up, advisers on Tudor agriculture recommended sowing the meadows with a mixture of clovers, yarrow, tormentil and English plantain. The ‘whole country is well wooded and shady’, a Frenchman, Estienne Perlin, wrote in 1558, ‘for the fields are all enclosed with hedges, oak trees and several other sorts of trees, to such an extent that in travelling you think you are in a continuous wood’.3 English pigs amazed strangers with their size and fatness. The best chickens Polydore Vergil ever ate came from Kent. The horses were strong and handsome and were exported abroad. It was a thickened country, dense with locality. This was the wild thyme, oxlip and honeysuckle landscape that would form the remembered and dreamed-of background to a century of violent political and religious change. That is the definition of sixteenth-century England: government bordering on tyranny in a country filled with sweet musk roses and eglantine.

The sixteenth century was a time to be in land. The weather was improving and more children were surviving into adulthood. The number of people in England was rising faster than the amount of food that could be grown for them. With a mismatch of supply and demand, food prices rose, tripling between 1508 and 1551, and rents rose with them. Agricultural land in the sixteenth century was the most reliable source of cash there was. But the ability to deliver the increased yields depended on returning fertility to the ground. A mixed country, in which there was plenty of grazing, much of it already enclosed, was a recipe for financial success. Meadows were money in Tudor England and both these families were blessed with them. Much of the story that follows here – of ideological courage and daring in the face of power; of families squabbling to get their hands on an inheritance – would not have been possible without that pasture-rich background. Tudor gentry floated on grass.

1520s–1580s

Discretion

The Throckmortons

Coughton, Warwickshire

The Throckmortons’ story is the life-track of a family attempting to ride the traumatic cultural uproar of the Reformation. Over four generations spanning the sixteenth century, they played in and out of honesty and duplicity, loyalty and betrayal, integrity and opportunism. They were both a barometer of their time and the clearest possible demonstration that to be a member of the gentry was no feather bed to lie on. Thomas Fuller, the seventeenth-century church historian, would describe yeomen, the farmers who had no claim to gentility or any part in the government of the country, as ‘living in the temperate zone between greatness and want, an estate of people almost peculiar to England’.1 That shady, calm country between significance and poverty was a kind of Arcadia that was unavailable to the gentry. Their duty, broadly expressed, was to govern, and in doing so to run the risk of want, or worse.

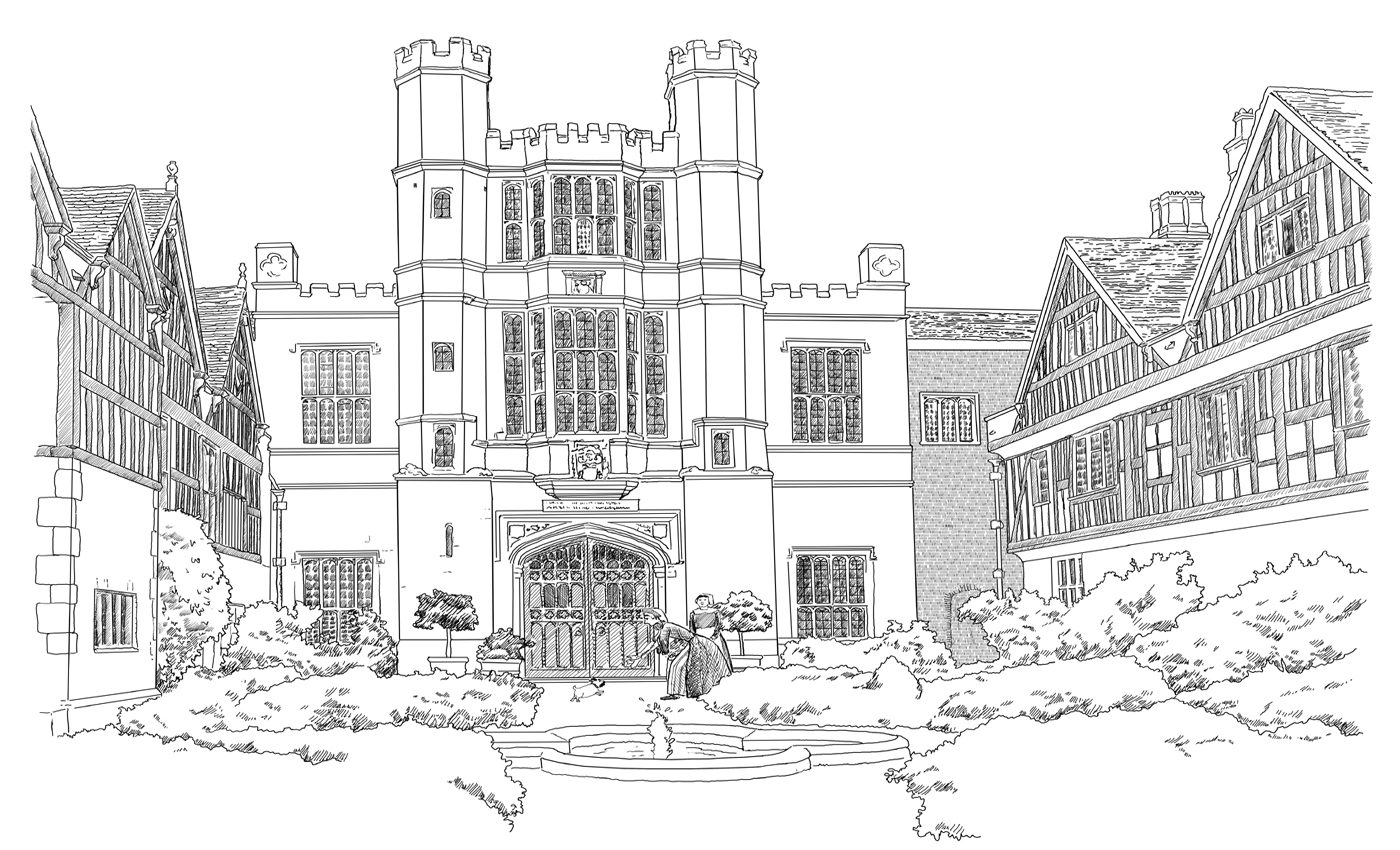

For at least three hundred years, the Throckmortons had been a Worcestershire family, who in the fifteenth century, partly by marriage, partly by purchase, had acquired lovely Warwickshire estates around Coughton in the damp grassy valley of the river Arrow, as well as others in Buckinghamshire and Gloucestershire. The Throckmortons had been astute managers of land for generations, enclosing pastures and woods, running a Worcestershire salt pit in the fifteenth century and heavily involved in both sheep and cattle, consolidating holdings, looking to maximize revenues from their farms. They had navigated the chaos and challenges of the Wars of the Roses, shifting from one aristocratic patron and protector to the next, deploying the key tactic of gentry survival: the hedging of bets.

Coughton, as suited the Throckmortons’ nature, is just on the border of two different worlds: to the north, the small fields and dispersed farms and hamlets of the forest of Arden, ‘much enclosyd, plentifull of gres, but no great plenty of corne’;2 to the south, beyond the river Avon, the wide open ploughlands of ‘fielden’ Warwickshire. Neither was entirely specialized – there were corn fields in Arden and animals were bred and fattened on the barley and peas grown in the fielden country – but Coughton lay happily in the hazy boundary between them and as a result was a good and rich place to be.

Within yards of the part-timber, part-stone buildings of Coughton Court, so close that the modern garden of the house completely encircles it, Sir Robert Throckmorton rebuilt St Peter’s Church in the first years of the sixteenth century. Everything there was mutually confirming. The Throckmortons’ house, the beginnings of its new freestone, battlemented gateway, the dignified church, their tombs within it, the productive lands surrounding them, their own piety, their charitable gifts to local monasteries, their place as the local enforcers of royal justice, as magistrates and sheriffs of the county: this was an entirely continuous vision. Everything connected, from cows to God, from periphery to centre, from the poor to the King, from the Throckmortons’ own self-conception and self-display to the nature of the universe. Go to Coughton today, and very faintly, beyond the ruptures of the intervening centuries, the notes of that harmonic integrity can still be heard.

They were a pious family.3 Sir Robert’s sister Elizabeth was an abbess, and two of his daughters were nuns. In 1491, his eldest son, the infant George, had been admitted to the abbey at Evesham, as a kind of amateur member, for whose soul the monks would pray. The family was chief benefactor of the guild of the Holy Cross at Stratford. In 1518 Sir Robert Throckmorton, now in his late sixties, decided to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He wrote a will before leaving, which is thick with late medieval piety. Masses were to be sung for his soul at Evesham to the south and by the Augustinian canons at Studley to the north. Dominicans in Oxford and Cambridge and the poor in the almshouse he had set up in Worcester were all to receive money to pray for his soul in purgatory. A priest in the chantry at Coughton was ‘to teache grammer freely to all my tenantes children’.4 The church itself was to be glorified with beautiful stained glass and gilded and painted saints. There was to be no shortage of Throckmorton heraldry. An altar tomb made of Purbeck marble was built in the nave for Robert’s own body to lie in one day, surrounded by this evidence of his piety and works. He had rebuilt the church as a reliquary for Throckmortonism. The whole building was a Throckmorton shrine. There was no gap between social standing and goodness or between the metaphysical and the physical. It was all part of a single fabric, like Christ’s coat at the crucifixion, ‘without seame, woven from the top thorowout’. If the Plumpton story was about disjunction and failure, this Throckmorton vision was of integration and wholeness.

Robert was never to occupy the tomb he built for himself. When in Rome, en route to the Holy Land, he died and was buried there, and his son George, born in 1489, came into the inheritance.

George had been married since he was twelve to Kathryn Vaux, and from about 1510 they began producing an extraordinary number of children, 19 in 23 years, most of whom lived until adulthood. Lands, localism, children, a household, local politics and the law: all of that was a dominant reality in George’s life. But the Throckmortons were far from parochial. Both George’s and Kathryn’s fathers had been close allies and courtiers to Henry VII. George would have considered Westminster and Whitehall his own to conquer. After some years learning the law in Middle Temple, he had entered the court of Henry VIII in 1511, fought alongside the King in France and was knighted in 1516. Royal favours began to trickle down: he became steward of royal estates and keeper of royal parks in Warwickshire and Worcestershire.

There is one minor incident which stands out from this steady progress. In the winter of 1517–18, he killed a mugger called William Porter who had come at him ‘maliciously’ in Foster Lane, the Bond Street of its day, off Cheapside, full of goldsmiths’ shops. It is possible George had been buying jewellery and his attacker was trying to rob him. George had slashed out at the man ‘for fear of death and for the salvation of his own life’ and killed him. A royal pardon followed.5

This was all entirely conventional: it was what people like George Throckmorton did with their lives. Legal competence, marriage and children, effective violence at home and abroad, minor functions at court and in Warwickshire, the management of the lands: this was the gentry in action, as it had been throughout the Middle Ages, the central, universal joint of English culture.

George Throckmorton could look forward to a life of unremitting and blissful normality. He was his father’s son, pious, efficient, forthright, courteous, sociable, capable both of performing duties for his social and political superiors and of attending to Throckmorton wellbeing.

The 1530s ensured that would not happen. For two or three years, Henry VIII had come to think that his marriage to his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, was cursed. Leviticus said as much. The King had offended God by marrying her and God had ensured she would bring him no son. Catherine was now too old to bear children and, anyway, since the spring of 1526 the King had been entranced by one of Catherine’s ladies in waiting, the young Kentish gentlewoman Anne Boleyn, with whose family Henry had long been familiar. He thirsted for divorce, to bed Anne Boleyn and to continue his dynasty. But a divorce was impossible. When his chief minister, the brilliant and deeply loathed Cardinal Wolsey, proved himself incapable of bringing it about, Henry’s desire for Anne, for freedom of action and for legitimacy all fused into one, overlapping, multi-headed crisis.

George Throckmorton, who was forty in 1529, found himself embroiled in every part of this crisis. Before Wolsey’s disgrace he had been working for him at Hampton Court, acting as the Cardinal’s agent in confiscating the monastic lands Wolsey needed at this stage to endow his new college at Oxford (which later would become Christ Church). When the King dismissed Wolsey for his inadequacies over the divorce in November 1529, tides of loathing swept over the fallen man. All the arrogance, regal style, vaingloriousness and independence of mind that he had shown in office were thrown back at him. Throckmorton might have been tainted with these connections but he managed to slip out from under them. At Hampton Court he had made friends with Wolsey’s rising assistant, the brewer’s son Thomas Cromwell, sending him gifts of £20 and a greyhound, asking for some sturgeon and quails in return, with the assurance that he was his friend and ‘hoping you wyll see me no loser’.6 Now, as Cromwell moved towards the centre of power, that connection came good. George’s son Kenelm went into service as a member of Cromwell’s household and George himself was made a member of the commission looking into the possessions Wolsey had claimed in Warwickshire.

It looked as if Throckmorton was calmly doing what his forefathers had done, easily sliding from one power-allegiance to the next, the traditional method by which successful gentry families survived from generation to generation. But the Reformation was more than just another power shift. As liberating juices ran into the crannies of English minds, the bound-together world of inheritance, piety and service, which his father, dead in Rome, had left to him twelve years before, came under threat. Lutheran ideas; Thomas Cromwell’s ambitions for a new and reformed relationship of church and state; the King’s desire for a new and possibly unholy divorce and marriage: this was not only a crisis for England. It was a life crisis for George Throckmorton himself.

In 1529 he had been elected to the Reformation Parliament, which met from time to time, without re-election, until 1536. That parliament was the instrument, deftly steered by Thomas Cromwell, through which the Reformation was brought to England. In one Act after another, church independence was eroded and the authority of the crown enhanced. Cromwell made the English state watertight: church money and lands were channelled towards the crown; no appeals were allowed to any authority outside England, especially not to the Pope; and increasingly repressive laws were passed against anyone who disagreed with royal policy, culminating in the 1534 Act of Supremacy and the Treasons Act, by which the King was acknowledged as supreme in church and state. Any disagreement was punishable by death. The cumulative effect of the parliament was to destroy the role of the Pope, the inheritance of St Peter, and put secular terror in its place.

From his actions and words, it is clear that George Throckmorton was agonized by the conflict of allegiances. Crown or family, his past or his future? His father’s church or the King’s? To which should he be more loyal? Half secretly, he began to oppose Henry’s reformation of church and state. But the whisper system of Thomas Cromwell’s listening network heard much of it, and although the chronology is often confused, in Cromwell’s papers you can hear and see this Warwickshire gentleman a little clumsily and a little foolishly navigating the shoals and tides of the Tudor seas.

A mass of business passed through the 1530s House of Commons, the regulation of towns, the tanning of leather and the dyeing of wool, the sowing of flax and hemp, the duties on wines, laws against eating veal (to preserve the stock of cattle) and for the destruction of choughs, crows and rooks (to preserve corn crops), for paving the Strand and ‘for the saving of young spring of woods’, against ‘excess in apparel’, and, amidst all this ordinary business, the cataclysmic ‘Appeals to Rome forbidden’.7

All England was talking of the changes confronting them. Throckmorton liked to meet a group of Parliament friends for dinner or supper in an inn called the Queen’s Head in Fleet Street. Others met and talked to him in private places around the City: the garden of the Hospital of St John, just north of the walls; or in a private room in the Serjeants’ Inn near the Temple; or at other inns in Cheapside, the shopping hub of the City where he had been mugged years before. London was full of these evening conversations between like-minded conservative gentry. ‘Every man showed his mynde and divers others of the parliament house wolde come thither to dyner & soup and comun with us.’ Usually, ‘we wolde bidde the servaunts of the house go out and in lik maner our owne servaunts because we thought it not convenient that they shulde here us speke of such mattiers’.8 But conversations were reported and to Cromwell this joint and repeated privacy looked conspiratorial.

George’s distinguished cousin and priest William Peto, a Franciscan friar and Catherine of Aragon’s confessor, summoned him for a private and urgent conversation. He told George it was his duty to defend the old church in Parliament, and ‘advised me if I were in the parliament house to stick to that matter as I would have my soul saved’.9 Death, and with it a sense of martyrdom, was in the air. But Peto also had some more intriguing information. He had just preached a sermon to the king at Placentia, the Tudor pleasure palace in Greenwich, violently denouncing anyone who repudiated his wife, lambasting the courtly flatterers in the stalls beneath him and warning Henry that Anne Boleyn was a Jezebel, the harlot-queen who had worshipped Baal, and that one day, dogs would be licking Henry’s blood, as they had her husband Ahab’s.

A tumultuously angry king left the chapel and summoned the friar to come out into the palace garden. In this atmosphere of alarm and terror, Peto took his life in his hands and addressed the King directly. Henry could have no other wife while Catherine of Aragon was alive; and he could never marry Queen Anne ‘for that it was said he had medled with the mother and the daughter’.10 To have slept with one Boleyn, let alone two, would in the eyes of the church make marriage to any other Boleyn girl illegal.

Peto fled for the Continent but left Throckmorton in London with his injunctions to martyrdom. How far was this from the comforts of Coughton, fishing in the Arrow or improving his house, completing his father’s new gateway! Throckmorton was swimming beyond his ken. Sir Thomas More, probably just on the point of resigning as Lord Chancellor,

then sent saye [word] for me to come speke with hym in the parliament chamber. And when I cam to hym he was in a little chamber within the parliament chamber, where as I do remember me, stode an aulter or a thing like unto an aulter, wherupon he did leane. And than he said this to me, I am viry gladde to here the good reporte that goeth of you and that ye be so a good a catholique man as ye be; and if ye doo continue in the same weye that ye begynne and be not afrayed to seye yor conscience, ye shall deserve greate reward of god and thanks of the kings grace at lingth and moche woorship to yourself: or woordes moche lik to thies.11

Throckmorton was flattered that these great men should be considering him as their advocate in Parliament. He was as vulnerable as anyone to the vanity of the martyr and prided himself on his courage and forthrightness as a man who was not frightened by princes or power. He wanted to be known, he wrote, as ‘a man that durst speake for the comen wilth’.12 He was not only a Catholic; he was a Warwickshire knight, whose tradition was to speak for the Commons of England. Peto had told Henry himself that his policies would lose him his kingdom, precisely because the commonwealth could not follow them. But for Throckmorton how could that position play out in the high-talent bear garden of the Tudor court? How could he survive if he were to defend the ancient Catholic truths?

In search of guidance, Throckmorton visited John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester, soon like More to be martyred (when his headless body was left, as a lesson to others, stripped and naked on the scaffold all day until evening came), as well as the monk Richard Reynolds at Syon in Middlesex. He too would soon be dragged on a hurdle from the Tower to Tyburn, where with four others he would be hanged in his habit for resistance to Henry’s supremacy laws. Everyone Throckmorton consulted, to various degrees, advised him ‘to stick to the same to the death’. And everyone knew that word was no figure of speech. ‘And if I did not, I shulde surely be damned. And also if I did speke or doo any thing in the parliament house contrarie to my conscience for feare of any erthly power or punyshment, I shulde stande in a very havie case at the daye of Judgement.’13

The choice they put to him was to suffer now or suffer in eternity, suicide or spiritual suicide. This advice ‘entered so in my heart’ that it set George Throckmorton on a path of courage. God had to come before man, whatever the consequence for him or his family. He was remaining loyal to the inheritance his father had left him and in doing so was endangering his children’s future.

Then, quite suddenly, he was sent for by the King. When they met, Cromwell was standing at the King’s shoulder. Confronted with this, Throckmorton bore himself with a directness and integrity of which his mentors would have been proud. He repeated to the King what his cousin Peto had told him:

I feared if ye did marye quene Anne yor conscience wolde be more troubled at length, for that it is thoughte ye have meddled bothe with the mother and the sister. And his grace said never with the mother and my lorde privey seale [Cromwell] standing by said nor never with the sister nethir, and therfor putt that out of yor mynde.14

It must have been one of the most terrifying tellings of truth to power in English history. Henry had admitted his affair with Anne Boleyn’s elder sister but this candour and apparent intimacy did Throckmorton little good. He appeared in Cromwell’s papers as one of those Members of Parliament to be watched and not to be trusted. Cromwell was not replying to letters from George himself but instead wrote to him, advising him ‘to lyve at home, serve God, and medyll little’.15 Sewn in amongst Tudor tyranny and threat were these repeated moments of forgiveness and advice, like sequins of grace, anti-sweets, sugar coated in bile.

But ‘meddle little’? Cromwell’s language might have been tolerant; it was scarcely forgiving. There is a plaintive recognition of that in Throckmorton’s letter to him: ‘Ye shall see I wyll performe all promesys made with you.’

From other places around the country, off-colour notes arrived on Cromwell’s desk. From Anthony Cope, a Protestant Oxfordshire squire and Cromwell loyalist: ‘It grieves me to find [the King] has so fewe frendes in either Warwick or Northamptonshire. Mr. Throkmerton promised he would assist me to the best he cold. Nevertheless, secretly he workith the contrary.’ From Sir Thomas Audley, one of Henry’s hatchet men, who presided over a sequence of show trials and executions in the mid-1530s: ‘Mr. Throgmorton is not so hearty in Warwickshire as he might be.’16

Not to be hearty in mid-1530s England, at least after the passing of the Treasons Act in 1534, one of the ‘sanguinolent thirstie Lawes’ by which men and women ‘for Wordes only’17 were condemned to death, was a dangerous position to be in. Thomas More and John Fisher would both be executed the following year on the basis of words alone. Anne Boleyn and her so-called lovers (which included her brother) were beheaded on the same grounds. Many monks were executed in the 1530s for doing no more. And George had been firmly identified with them as part of this verbal opposition. In January 1535, he wrote from Coughton to the worldly diplomat and trimmer Sir Francis Bryan: ‘I hear that the kynges grace shuld be in displeasure wythe me. And that I shuld be greatly hyndred to hym, by whom I know not.’18

Throckmorton was a marked man, if not yet a condemned one, and as an escape from that predicament, he attended to his lands in Warwickshire and Worcestershire, retreating to the comforts of Coughton, consolidating estates, negotiating with his neighbours and with Cromwell for advantages and openings for himself and his children. Life had to go on. Acting as the King’s servant, Throckmorton continued with his normalities, sending in accounts of the royal woods at Haseley, where he was the bailiff, and serving as a commissioner in collecting tax from clergy in Warwickshire, guiding church money towards the royal coffers. On his new gateway at Coughton, he put up two coats of arms: his own and Henry Tudor’s.