The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters

Ischia offered the early Iron Age Greeks more than exquisite comfort. When the first settlers came here in about 770 BC from the Aegean island of Euboea, they set up the earliest, most northern and most distant of all Greek colonies in Italy. They chose it because the northern tip of the island provides the perfect recipe for a defensible trading post: a high, sheer-walled acropolis, Monte Vico, with sheltered bays on each side, one protected from all except northerlies, the other open only to the east. Between the two a shallow saddle is rich in deep volcanic soils where a few vine and fruit trees still grow among the pine-umbrellaed villas and the swimming pools. Here, beginning in the early 1950s, the archaeologist Giorgio Buchner excavated about five hundred eighth- and seventh-century BC graves which reveal the lives of people for whom the Homeric poems were an everyday reality.

This little Greek stone town was called Pithekoussai, Ape-island, perhaps from the monkeys they found here on arrival, or more interestingly as a name suitable for people who were seen from the mainland as vulgar and adventurous traders, laden with cash, irreverent and with uncertain morals, enriching themselves on the edge of the known world (pithekizo meant ‘to monkey about’). It was an astonishing and wonderful melting pot, four thousand people living here by 700 BC, nothing half-hearted about it, nor apparently militaristic. People from mainland Italy, speaking a kind of Italic, were living here, with Phoenicians from Tyre and Sidon, Byblos and Carthage, Aramaeans from modern Syria and Greeks. The archaeologists found no ethnic zoning in the cemetery. All were living together and dying together, buried side by side. There was little apparent in the way of ethnic gap between these people. It was a deeply mixed world. Iron with the chemical signatures of Elba and mainland Tuscany was worked here in the blacksmiths’ quarter and sold on to clients in the Near East. Trade linked the island with Apulia, Calabria, Sardinia, Etruria and Latium as well as the opposite Campania shore. No other Greek site in Italy has objects from such a vast stretch of the Iron Age Mediterranean.

Buchner found no hint in any of the graves of a warrior aristocracy. The only blades were a few iron knives, awls and chisels. The leading members of the Pithekoussai world were from a commercial middle class, some with small workshops for iron and bronze, many with slaves of their own. The style of burial marks the difference between those classes: the slaves hunched foetally in small and shallow hollows, no possessions beside them; their masters, mistresses and their children laid out supine, in plain and dignified style, accompanied by simple but beautiful grave goods.

Much of their pottery came from Corinth and Rhodes, and what they didn’t import, they copied. Small Egyptian scarabs were often worn as amulets by the children and went to their graves with them, along with stone seals from northern Syria and one or two Egyptian faience beads. There are some fine red pots made in the Phoenician city of Carthage on the North African coast, and silver pins and rings from Egypt. A tomb of a young woman buried in about 700 BC was found with her body surrounded by little dishes from Corinth and small ointment jars, seventeen of them, around her, a dressing-table-full. Men also had little fat-bellied oil jars with them, some no more than an inch high and an inch across, pocket offerings, maybe used in the funeral rites. A fisherman was buried with his line and net; only the bronze fish hook and the folded-over lead weights of the net have survived. These men were all buried in the way of Homeric heroes, their bodies cremated on wooden pyres, and then interred with the charred wood and their possessions beneath small tumuli.

Nothing is coarse or gross. Big-eyed sea snakes and fluent, freely-drawn fish decorate the grey-and-ochre pottery. There are flat-footed wine jugs, suitable for a shipboard table. There is one big dish decorated with a chariot wheel, perhaps another faint heroic memory. Some pots are decorated with griffins from patterns that had their distant origins in Mesopotamia, others with swastikas that probably originated just as long ago in the Proto-Indo-European cultures of the Caspian steppe.

Fusion and mixture, a kind of mental mobility, is the identifying mark of this little city. It was not a luxury civilisation, but as you spend a morning walking around the empty, cool marble halls of the Pithekoussai Museum in the Villa Arbusto, peering in at the pots, you can feel the stirring of life in this distant and adventurous place 2,700 years ago. It doesn’t take much to see the wine being mixed in these bowls, poured from these jugs or drunk from these cups, nor the glittering fish hauled up in these nets or the goods loaded on distant quays and beaches and sold from here to curious buyers on the mainland of Italy.

And the museum holds its surprises. One late-eighth-century cratēr originally made in Attica, a bowl for mixing wine and water, depicts this world in trouble.

On its grey and rapidly painted body, a ship floats all wrong in the sea, turned over in a gale, its curved hull now awash, its prow and stern pointing down to the seabed. Everything has fallen out. Wide-shouldered and huge-haunched men are adrift in the ocean beneath, their hair ragged, their arms flailing for shore and safety. Striped and cross-hatched fish, some as big as the men, others looking on, swim effortlessly in the chaos. A scattering of little swastikas does little to sanctify this fear-filled waterworld. One man’s head is disappearing into the mouth of the biggest fish of all. It is a disaster, fuelled by the fear the Greeks had of the creatures of the sea, alien animals which, as Achilles taunts one of his victims, ‘will lick the blood from your wounds and nibble at your gleaming fat’. The scene is no new invention; it is painted with all the rapidity and ease of having been painted many times before.

There is no need to attach the name of Odysseus to this; nor of Jonah, the Hebrew prophet swallowed by a fish, his story exactly contemporary with this pot. It is merely the story of life on the Iron Age seas, the reality of shipwreck, the terror of the sea as a closing-over element filled with voracious monsters. In a later, Western picture, the large-scale catastrophe of the ship itself would have been the focus. Here it is pushed to the outer margin and made almost irrelevant; the central characters are the men, their hair and limbs out of order, the experience of human suffering uppermost. In that way, this is a picture from the Homeric mind.

Then, in a room hidden deep in the museum, you find the other transforming dimension of Pithekoussai: these people wrote. Shards from the eighth century BC are marked or painted with tiny fragments of Greek. One has the name ‘Teison’, perhaps the cup’s owner. A second, on a little fragment of a cup, says ‘eupoteros’ – meaning ‘better to drink from’. A third, also in Greek, written like the others with the letters reading from right to left as they are in Phoenician, and with no gaps between the words, says, fragmentarily, ‘… m’ epoies[e]’. The verb poieo has the same root as ‘poetry’, and the inscription means ‘someone whose name ended in -inos made me’ – Kallinos, Krokinos, Minos, Phalinos, Pratinos? This is no scratched graffito, but painted as part of the Geometric design. It is another first: the oldest artist’s signature in Europe.

By 750 BC at the latest, writing had seeped into all parts of this expanding, connecting, commercial, polyglot world. Pithekoussai is not unique. Eighth-century inscriptions, many of them chatty, everyday remarks, with no claim to special or revered significance, have survived from all over the Aegean and Ionian Seas. These aren’t officious palace directives, but witty remarks, sallies to be thrown into conversation.

And, as a wonderful object on Ischia reveals, Homer played his part. It was found in the tomb of a young boy, perhaps fourteen years old, who died in about 725 BC. He was Greek, and unlike most of the children was cremated, an honour paid to his adulthood and maturity. In his grave his father placed many precious things: a pair of Euboean wine-mixing bowls from the famous potters of their home island, jugs, other bowls, and lots of little oil pots for ornaments.

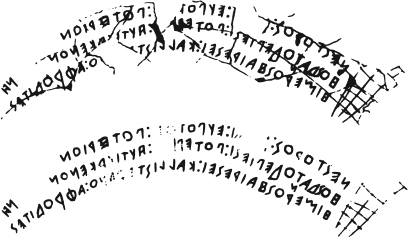

The greatest treasure looks insignificant at first: a broken and mended wine cup from Rhodes, about seven inches across, grey-brown with black decoration and sturdy handles. Scratched into its lower surface on one side, and not at first visible but dug away a little roughly with a burin, are three lines of Greek, the second and third of which are perfect Homeric hexameters. This is not only the oldest surviving example of written Greek poetry, contemporary with the moment Homer is first thought to have been written down, it is also the first joke about a Homeric hero.

In the Iliad, during a passage of brutal bloodletting and crisis for the Greeks, the beautiful Hecamede, a deeply desirable Trojan slave-woman, captured by Achilles and now belonging to Nestor, mixes a medicinal drink for the wounded warriors as they come in from battle: strong red wine, barley meal and, perhaps a little surprisingly, grated goat’s cheese, with an onion and honey on the side. Hecamede did the mixing in a giant golden, dove-decorated cup belonging to Nestor, which a little pretentiously he had brought from home: ‘Another man could barely move that cup from the table when it was full, but old Nestor would lift it easily.’

There are Near-Eastern stories of giant unliftable cups belonging to heroes from the far distant past. And tombs of warriors have been found on Euboea from the ninth century BC which contain, along with their arms and armour, some big bronze cheese-graters, now thought to be part of the warrior’s usual field kit, perhaps for making medicines, perhaps for snacks.

So this little situation – the Nestor story, the unliftable cup, the Euboean inheritance, and the presence at a drinking party of wonderfully desirable women – has deep roots. Remarkably, they come together in the joke and invitation scratched on the Ischian cup. ‘I am the cup of Nestor,’ it says,

good for drinking

Whoever drinks from this cup, desire for beautifully

crowned Aphrodite will seize him instantly.

The Pithekoussaian trader was turning the Homeric scriptures upside down. This little cup was obviously not like Nestor’s cup, the very opposite in fact: all too liftable. Its wine was not to cure wounds received in battle. It was to get drunk at a party. And drinking it would not lead on to an old man’s interminable reminiscing over his heroic past. No, the cup and the delicious wine it contained would lead on to the far more congenial activity of which Aphrodite was queen: sex. This elegant little wine cup, treasured far from home amid all the burgeoning riches, gold and silver brooches, success and delight of Pithekoussai, a place supplied with beautiful slave-girls taken from the Italian mainland, was for the drinking of alcoholic aphrodisiacs. The inscription was an eighth-century invitation to happiness.

The distant past might often seem like the realm of seriousness, but the Ischian cup re-orientates that. The first written reference to Homer is so familiar with him, and so at ease with writing, that in mock Homeric hexameters it can deny all the seriousness Homer has to offer. Homer and his stories were so deeply soaked into the fabric of mid- to late-eighth-century BC Greek culture that dad-style jokes could be made about him. And that makes one thing clear: here, in 725 BC, is nowhere near the beginning of this story. The original Homer is way beyond reach, signalling casually from far out to sea.

There is only one aspect of grief associated with the sophisticated optimism and gaiety of this story, and it is inadvertent. The father offered this cup to his fourteen-year-old son in the flames of the funeral pyre, where it broke into the pieces which the archaeologists have now painstakingly gathered and restored. Death denied the boy the adult pleasures to which these toy-verses were inviting him. And that is another capsule of the Homeric condition: the Odysseyan promise of delight enclosed within the Iliadic certainty of death.

SIX

Homer the Strange

THE PITHEKOUSSAI WINE CUP marks the limits of the written Homer. It is the edge of a time-cliff: step beyond it, further back in time, and the ground falls away. In that disturbingly airy and insubstantial world out beyond the cliff face, before the eighth century BC, Homer is unwritten, existing only in the minds of those who knew him.

It is a disorientating condition for our modern culture: how can something of such importance and richness have had no material form? How can the Greeks have trusted so completely to their minds? At home in Scotland, I sometimes go up to the edge of the sea-cliff above the house, looking down to the fulmars circling in the four hundred feet of air below me. Again and again, the birds cut their effortless discs in that space, turning in perfect, repetitive circles, in and out of the sunlight, scarcely adjusting a feather to the eddies, but calm and self-possessed in all the mutability around them; and I have thought that in that fulmar-flight there may be a model of the Homeric frame of mind. You don’t need to fix something to know it. You know it by doing it again and again, never quite the same, never quite differently. You may even find, in that tiller-tweaking mobility – a slight adjustment here, another there – that you know things which the rigid and the fixed could never hope to know. The flight is alive in the flying, not in any record of it. And perhaps we, not Homer, are the aberration. Of about three thousand languages spoken today, seventy-eight have a written literature. The rest exist in the mind and the mouth. Language – man – is essentially oral.

Until the twentieth century, no one had any idea that Homer might have existed in this strange and immaterial form. It was the assumption that Homer, like other poets, wrote his poetry. Virgil, Dante and Milton were merely following in his footsteps. The only debate was over why these written poems were in places written so badly. Why had he not written them better? Both the Iliad and the Odyssey are riddled with internal contradictions. No self-respecting poet would allow such clumsiness.

The great eighteenth-century Cambridge scholar Richard Bentley – the dullest man alive, according to Alexander Pope, ‘that microscope of Wit,/Sees hairs and pores, examines bit by bit’ – thought that Homer wrote

a sequel of songs and Rhapsodies, to be sung by himself for small earnings and good cheer, at festivals and other days of Merriment; the Ilias he made for the men and the Odysseis for the other Sex. These loose songs were not connected together in the form of an epic poem till … about 500 years after.

Homer was no longer a genius; he was the work of an editor-collector, perhaps not entirely unlike Professor Bentley himself. Later microscopes of wit thought there was not even one author, but a string of minor folk poets whose efforts had been brought together by the great Athenian or even Alexandrian editor-scholars. The Prince of Poets had been dethroned. The scholars had won. And so the nineteenth century was animated by the debates between Analysts and Unitarians, those who thought Homer had been many and those who continued to maintain that he was one great genius.

The argument lasted for over a century, largely because of the sense of vertigo a multiple Homer induced. If Homer was dissolved into a sequence of folk-poets, one of the greatest monuments of Western civilisation no longer existed. Nevertheless, these were the preconditions for the great discoveries about Homer made in the early twentieth century by the most brilliant man ever to have loved him.

Milman Parry is a god of Homer studies. No one else has made Homeric realities quite so disturbingly clear. Photographs show what his contemporaries described, a taut, focused head, a man ‘quiet in manner, incisive in speech, intense in everything he did’. There was nothing precious or elitist about him, and his life and mind ranged widely. For a year he was a poultry farmer. Along with the technicians at the Sound Specialties Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, he was the first to develop recording apparatus which didn’t have to be interrupted every four minutes to change the disc. He took his wife and children with him on his great recording adventures in the Balkans, and at night sang songs to them which mimicked and drew on the epic poems he had heard in the day. At Harvard, where he became an assistant professor, he took to washing his huge white dogs in the main drinking-water reservoir for the city, stalking about the campus in a large black hat with ‘an aura of the Latin quarter’ about him, regaling his students with the poetry of Laforgue, Apollinaire, Eliot and e.e. cummings. Supremely multilingual, at home in Serbo-Croat, writing his first articles and papers on Homer in French, this was the man who pulled Homer back from its academic desert into life.

Milman Parry, 1902-35

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов